"The Wright Stuff III: Movies Edgar Has Never Seen”

"The Wright Stuff III: Movies Edgar Has Never Seen” is Edgar Wright’s third season of programming at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, which commences this coming Friday with a double feature of Frank Tashlin’s

The Girl Can’t Help It and Allan Arkush’s

Get Crazy (a triple, if you include the midnight screening of Wright’s own

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) and concludes the following Friday night with Robert Culp’s

Hickey and Boggs, Ivan Passer’s

Cutter’s Way and a midnight encounter with W.D. Richter’s

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension. I had the pleasure of a phone conversation with Wright this past week to talk about this latest gathering of cinematic goodies, the plight of 35mm, and even the recent passing of a titan of iconoclastic British cinema. Here’s what that conversation sounded like.

*****************************************

DC: Congratulations on the new series of films coming up at the New Beverly this week. Whenever a series like this is announced, you hear things like, “Damn, I’m on the wrong coast!” Or in your case often I’ll see someone say something like, “When are you gonna do one of these in the U.K.?”

EW: I get that all the time. It always happens to me with the

Scott Pilgrim midnight shows. Every time I tweet about there being a midnight show, people say, “Why can’t you bring it to New York? Why can’t you bring it to Oklahoma?” And I have to say, “Guys, I don’t arrange these screenings.” I just retweet them if I’ve seen them, and if I’m in town maybe I’ll stop by.

DC: It’s not Edgar Wright’s traveling

Scott Pilgrim tent revival, with you taking the movie from town to town.

EW: Right! It’s not me organizing them. It’s up to the rep cinemas to decide to screen it. I did one at the New Beverly and then one up at the Castro. But for me, whether it’s

Scott Pilgrim or any of the film series I’ve done, it’s kind of a hobby, the kind of thing I would do in the evening anyway—go and watch films at rep houses! The idea with this season, because I’d done two already comprised of my favorite films, it seemed right that I should do a kind of hostile takeover and program only ones that I’ve always wanted to see.

DC: I actually put my own list together of movies I’d never seen, and as I was doing it the first thing I thought about was inviting the chorus of disbelief—“What, you’ve never seen

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!?”

EW

EW: Well, I don’t claim to be an encyclopedia of all cinema. I’m 37, and I’m still learning. When I was a kid, a teenager, I was trying to watch as much stuff as I could. And even when I started working in TV and then in film, I’d keep up with the current releases more than watching old classics. But the main thing was, there were a lot of films in the back of my mind that I’d thought to myself, “I’d like to see that on the big screen first.” And as such, a lot of the classic movies, especially westerns or big epics, whether it’s John Ford or Kurosawa, some of them I’d see on a small TV with classmates or friends and afterward I sometimes felt like I still hadn’t really seen them. I have a vivid memory of seeing

My Darling Clementine on an 18-inch TV in art college and by the time the movie was finished the entire class had fallen asleep. Probably not the best way to be introduced to these types of films.

DC: So let’s take a look at the upcoming schedule. When I looked at it, it felt like it was a two-week program packed into one week.

EW: Well, I actually convinced the New Beverly to let me do one double feature a night . I released what my window of availability was, and their window as well, which was eight nights, four double bills, and I said, “Can we do eight nights, eight double bills?” (Laughs) I don’t know when I’m gonna do this again. It’s probably gonna be my last one for a while, so I was thinking, “I want to pack in as many movies as possible!” I thank the New Beverly for kind of changing their normal M.O.

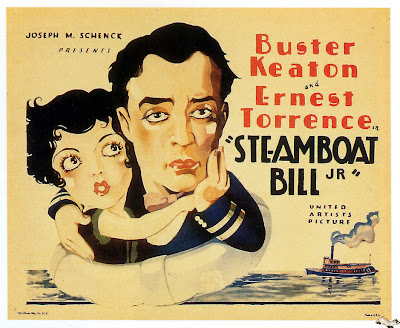

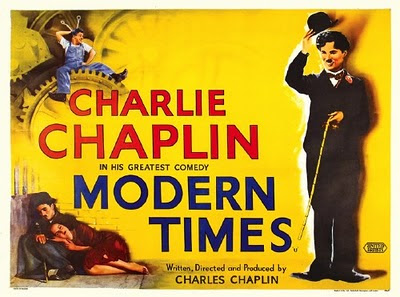

DC: Again, this is a series built around movies that you have never seen. Your personal directing style, the way you use the camera with such agility to tell jokes visually, suggests a certain familiarity and affinity with the sort of visually oriented slapstick of early silent comedy as well as the inventive verbiage of screwball comedy. Yet there are three major comedies of these eras-- Buster Keaton’s

Steamboat Bill, Jr., Charlie Chaplin’s

Modern Times and the great W.C. Fields vehicle

The Bank Dick-- in your lineup. Is silent or screwball comedy any more of a gap in your experience than the Ozu you cited on your blog?

EW: I have seen

Tokyo Story! (Laughs) But that was one of those I remember being ruined when I watched it at art college. It was just the worst possible way to watch it. But what’s interesting is that I find, with a lot of classic silent comedy, I remember seeing it on TV when I was very young, but it was usually in the form of a compilation. I remember seeing lots of documentaries and compilations—classic Chaplin and Keaton clips, but never necessarily the whole movie. When I watched

The Gold Rush, for example, I hadn’t seen the whole feature, but I’d certainly seen the most familiar excerpts. Same with Buster Keaton. I know I’ve seen that famous shot from

Steamboat Bill, Jr., but I haven’t seen the whole feature. Very rarely have I seen any of them on the big screen. With each of those performers, I’ve seen

other classic titles but not these particular ones. Growing up, the black-and-white comedy stars I was very familiar with were Harold Lloyd, who used to get shown a lot in the U.K., the Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy.

The Music Box is one of my earliest memories of watching any film.

But the same thing goes for Frank Tashlin, who is somebody who has been mentioned in reviews of my own films—I always thought, “Gosh, I have to see some of his movies!” And that influence gets into me regardless, probably because the people that I’ve been inspired by are fans of his, be it Joe Dante, Sam Raimi or Allan Arkush. Allan Arkush told me he was very pleased that

The Girl Can’t Help It and

Get Crazy were showing together, because he said

The Girl Can’t Help It is one of his favorite movies. And I grew up, as we all did, with Woody Allen, and Woody Allen refers back to Chaplin and the Marx Brothers. So, really, I was inspired by the people who were inspired by the classic comedy pioneers.

DC:

The Girl Can’t Help It and

Get Crazy, followed by

Scott Pilgrim, is in some ways a pretty zippy trip through the essence of rock and roll.

EW: Allan Arkush told me

Scott Pilgrim reminded him of

Get Crazy, so that seems like a perfect triple to me. Any hardened film geek is gonna watch all three in a row.

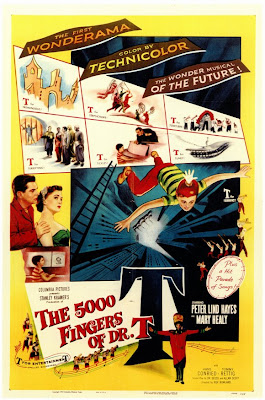

DC: One of the things that’s fun about anticipating a series like this is recognizing the connections that you make between movies that we might never have thought about. I looked at

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T and

Kwaidan and at first I didn’t get it. Then I started thinking about the fact that both movies have a deliberately nightmarish quality to them that makes them an unlikely but inspired combination. Did it take you a while to come up with the best pairings? And how long did it take you to cull down your possible selections to eight double features?

EW

EW: How it started was, at first I e-mailed a bunch of directors, actors and writers, told them what I was doing and said, give me your top-10 must-sees. Some of those people gave me lists that were enormous. Bill Hader’s list and Daniel Waters’ list were in the hundreds. Quentin Tarantino and Judd Apatow and Joss Whedon all gave me top 10s. So did John Landis and Joe Dante—actually, Joe’s was longer than 10. Then I threw it open to people on my blog, and that produced another thousand suggestions. Then I started looking for little links between films. I had to leave so many out. There were some that were so close to being scheduled that didn’t make it, which was disappointing, but some were left off because they do play a lot. I wanted to go for films that don’t get as much exposure.

DC: Did the availability of prints play a part in the way the program ultimately shaped up?

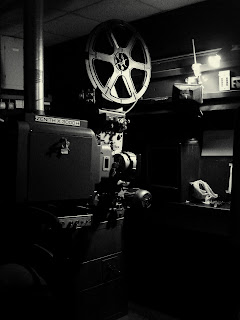

EW: Yeah, it did. It’s definitely getting to be a kind of dark time. I was surprised to discover that some films didn’t even have a decent print to be found, which is alarming. Julia Marchese at the New Beverly is circulating that online

“Save 35mm” petition because what’s happening is-- Obviously digital projection is going to become the norm, but I for one, and I know Quentin Tarantino agrees, feel that 35mm should never go away. It’s historically important. But some of the studios are actually shutting down their 35mm archival departments. I think Warner Brothers, beginning next year, are planning on not sending out any more 35mm prints of their films.

DC: Yeah. Fox has announced similar plans.

EW: It’s a very bittersweet thing to discover that your chances to see some of these films on 35mm are kind of dwindling very fast. It’s one of the main reasons I like doing these seasons at the New Beverly—sharing the experience. There is nothing better than watching the movies with a crowd. As home theater gets better, people don’t necessarily think about going out to see them. When I first announced the schedule, one person on my blog commented, “But a lot of these are on DVD or Netflix Instant!” And I had to think, yeah, you kind of missed the point. I know that. I own a lot of them myself. But that’s not necessarily the way I want to see them, especially for the first time.

DC: And maybe some people who wouldn’t necessarily come out for a revival program will get reminded about the difference between seeing them in a theater and making the movies something more than a commodity to store on a bookshelf.

EW: Absolutely. People sing the praises of Netflix Instant, but at the moment the quality of some of the copies of some older films they have available is really bad. There are some noir films in public domain that are just unwatchable. I can watch

Detour or

D.O.A., but I’m not exactly watching them in anything approximating a decent version. That’s why labels like Criterion are to be applauded. In many cases they’re not just restoring these films, they’re actually saving them. Thanks to them there’s now a definitive version of

Blast of Silence out there, a movie which many people may not have even known about before.

DC: What’s the double feature in the Wright Stuff III you’re looking forward to the most?

EW:

All of them, Dennis! Come on! (Laughs)

DC: (Laughs) I’m not gonna pin you down on just one? I mean,

I could pick one!

EW: No, I’m looking forward to all of them. One thing I want people to do is come out for the older movies.

DC: Yeah, I think it’s important to encourage people who might be all in for some of the more recent pictures to take a chance on some of the stuff that might not necessarily be in their wheelhouse of nostalgia or whatever. If you like stuff from the ‘80s, don’t be afraid of movies from the ‘30s or the ‘20s!

EW: Yeah, in a lot of rep houses you’ll get full houses for stuff from the ‘80s, but it’s important for people to come and see the black and white comedies as well. I’ve got good guests every night too. (A complete rundown can be found at

Edgar Wright Here-- DC.) Unlike my previous seasons, where I had people who made the movies coming along, for this one it’s just for the most part other directors and writers and comedians to do it with me, so it’s more like an intervention. My first question to them will be, “Why haven’t I seen this movie before?” (Laughs)

DC: And sometimes the people who actually made the movies are not as articulate about the actual thing as the movie’s fans are.

EW

EW: My proudest achievements with the two seasons I’ve done before has been the couple of times I’ve got filmmakers to come out, sometimes reluctantly, because maybe the film I’m showing of theirs was not a success, and get them to end up feeling differently about a movie they’ve made, and for them to see it with a packed house, or at least an appreciative audience. David Zucker and Jim Abrahams thought they might not even come to our screening of

Top Secret. He said, “

Top Secret was a disaster and I haven’t seen it since 1984.” And I convinced him to come out by saying, “This is gonna be the most partisan

Top Secret crowd you’re ever gonna see!” (Laughs) The first thing he said after it was finished was, “Yeah, that’s a good movie! It’s a funny movie!” But Walter Hill was reluctant as well to come out for

The Driver, which staggered me, because that’s probably my favorite film of his. So when he came out and saw the crowd he actually said, “This is the first time I’ve ever seen a full house for

The Driver.” He was genuinely touched by the response. I told him, “You realize this is a really influential film, for me and for other people.”

DC: Did he believe you?

EW: Yeah, I think so. The Q&A was so enthusiastic that I think he had to realize that there was a lot of love for

The Driver. Especially in the year that

Drive comes out, it’s important that more eyes see Hill’s film on the big screen. The D.N.A. of that film is definitely in

Drive.

DC: That was the one screening last year that I missed, and it still pains me to think about it.

EW: Well, what can I say, Dennis? It was great!

DC: Thanks a lot!

EW: Every time I do one of these screenings, someone always says, “Why don’t you record the Q&As or upload the video of it?” And my answer is always that I don’t because I’m a big believer in the importance of actually being there. That’s one of the things that creates excitement about it.

DC: Yep. You can’t get this stuff anywhere else.

EW: If you were there, it’s something you’ll remember. That’s what I like about the New Beverly—it’s relaxed and people tend to get a lot more candid in the Q&As there because it feels like you’re just kind of hanging out in somebody’s living room.

DC

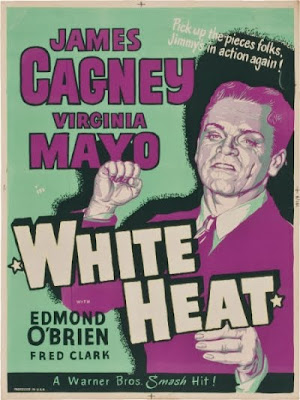

DC: The one double feature I’ll be very interested to hear your reaction to, as the director of

Hot Fuzz, is

Hickey and Boggs and

Cutter’s Way. That’s a very interesting combination of movies about male bonding through a specifically anti-establishment prism.

EW:

Hickey and Boggs is actually quite a difficult movie to track down. I’ve always wanted to see that.

DC: Again, it’s at the root of what’s at the root of a movie like

Hot Fuzz.

EW: Yeah, and as far as

Cutter’s Way-- One of the things that helped inspire the series is Danny Peary’s

Cult Movies book. I never actually had a copy of it, and recently Larry Karaszewski gave me a copy. I started looking through the book and thinking, “Wow! Still, 20 years later there’s a bunch of these I haven’t seen! I gotta get on this!” So much of this season is straight from Danny Peary.

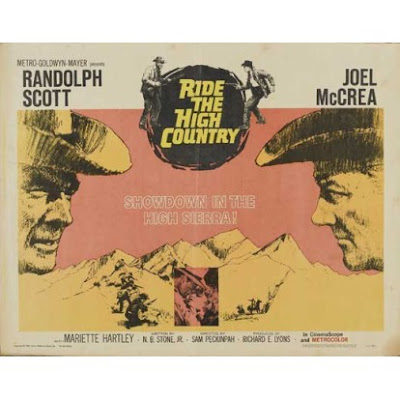

Cutter’s Way is in

Cult Movies and so is

The Girl Can’t Help it and

Ride the High Country.

DC

DC: Right after your series ends, the New Beverly has programmed a double feature of

Women in Love and

The Music Lovers in honor of the late, great Ken Russell. In America, especially for filmmakers of your generation, Ken Russell’s influence is probably more secondhand, more felt as ripples through the sensibilities of other filmmakers than by much direct contact. But as a young Brit, how aware were you of his legacy growing up? Was he an influence on you? Or do you think young directors were thinking about other filmmakers at that point?

EW: When I was growing up a lot of his films would be on TV, so I saw a lot of them—even some of the craziest ones. I was definitely aware of him, and I was a big fan of his composer biopics, which were unique and idiosyncratic. I remember watching

The Music Lovers and

Mahler when I was 12 or 13. And

Tommy, of course, is a huge film in the U.K. Only very recently I saw

Lisztomania for the first time. (Both laugh) It completely bowled me over. I couldn’t quite believe what I was seeing. I immediately went out and bought the soundtrack! Russell was also a larger-than-life personality, so he was very visible in the British press and on talk shows—an amazing character. I don’t know how much of an influence he was on me because I think he’s such a unique voice. You know what’s really sad, though? About four weeks ago I was talking with a fellow British director, Ben Wheatley, about people like Nicolas Roeg, John Boorman, Richard Lester and, in particular, Ken Russell, and we were saying how some of these people don’t get the contemporary love that they should in terms of their status as masters and their amazing bodies of work. We were talking about the fact that somebody should do a podcast series with these directors before they’re no longer with us. You know, somebody should sit down and talk to Ken Russell about his work. And then just a few days ago I e-mailed Ben and said, “Well, I guess we should have done that Ken Russell podcast, eh?”

DC: I’m reminded of an appearance Russell made here in Los Angeles a couple of years ago for the digital restoration of

Tommy. He got on stage with the documentarian Murray Lerner, and no matter how hard Lerner tried to get him to talk about the movie and his process of working, Russell played the dotty imp who would not give Lerner what he wanted

at all.

EW: Yeah, I don’t know how much of that was an act! (Laughs) He was genuinely one of the great British eccentrics, and I say that as a compliment, not as a negative.

DC: Well, he never toed the line in his movies, so if you’re familiar at all with his personality it shouldn’t be too unexpected that he wouldn’t do it in public either.

EW

EW: There’s a particular breed of directors who all began working around the same time, like many of the ones I just mentioned, who all have a specific vision but also are, in some respects, similar. So many of those films had sort of avant-garde tendencies that were then filtered into studio films, and that they could manage that is fascinating. Completely coincidental to his death, the BFI announced that they would be re-releasing

The Devils next year. I had a copy of the film on VHS, and when DVDs came in I think I gave it to a charity shop—one of the dumbest things I’ve ever done—thinking surely it’ll turn up on DVD soon, and of course it never did! That film is a juggernaut. It’s my favorite of his.

DC: There is some controversy over the fact that the re-release is of the X-rated theatrical version and not the uncut version Russell made, which includes the famous “Rape of Christ” sequence.

EW: Yeah, I’ve heard about that. But the fact of the matter is, the one that got released is still pretty strong! (Laughs) I don’t think people will be disappointed that it’s only the theatrical version! Ultimately it’s better to have

a version rather than

no version.

DC: Any final thoughts about the Wright Stuff III?

EW

EW: Oh, yeah, there’s gonna be a whole bunch of vintage trailers as well that Marc Heuck from the Nuart has put together. Usually I pick them myself, but he’s come up with an amazing selection of stuff to see that I think will surprise and delight everyone who comes out. I do this for fun, really. I don’t get paid to do it. I don’t get a cut of the box office. It’s literally just about that I like watching movies and I like to share that with audiences. Especially now more than ever it’s important to keep rep cinemas going, to be able to do stuff at the New Bev to remind people what it means to see these kinds of classic and cult movies with an audience. On 35mm.

**********************************