THE DENNIS AND EVAN FILM FESTIVAL Summer 2005 Movies (So Far) and a Week Spent with My Movie-Mad Nephew

Here it is, a full month since my nephew Evan arrived from McKinleyville, California, a town just north of Eureka, in the heart of Humboldt County, for a week of nonstop movie-going, balanced by a week of nonstop DVD-watching in the off hours, and I still don't feel like I've fully recovered. I haven't seen a movie in a theater since Friday, July 1.* I want to see Fantastic Four, but right now another blockbuster, after that week of almost nothing but summer blockbusters, just sounds exhausting (late appearances by some encouraging reviews and a first-person account from a friend have bolstered my hopes that it might be worth a look, however, despite all the conventional wisdom suggesting otherwise). I'm hoping that time won't run out on my opportunity to see Alice Wu's Saving Face, a romantic comedy starring Joan Chen, though it's down to one more week at a second-run house in Pasadena, and who knows if it'll be there next Friday. And I've also got designs on two very different documentaries, Murderball and The Aristocrats, Tim Burton's film of Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Walter Salles' take on J-horror Dark Water, Miranda July's sleeper hit Me and You and Everyone We Know, March of the Penguins, perhaps Don Roos' Happy Endings and, in another instance of unexpectedly good reviews piquing my previous absolute lack of interest, Vince Vaughn and Owen Wilson in Wedding Crashers (that moist sound you just heard was frequent reader Virgil Hilts indulging in the Spit Take to End All Spit Takes-- Virg, they promise me that there's only one cameo appearance in this one by another comic actor who routinely rotates inside the same sphere as Mssrs. Vaughn and Wilson, and it's not the short, obnoxious guy).

BEETLE JUICE

But before I start Summer Movie Indoctrination Phase Two, I really should talk a little bit about what Evan and I saw during that image-and-sound saturation bombardment that comprised our recent big movie week. The Dennis/Evan Film Festival actually started for me the afternoon before Evan arrived at Los Angeles International Airport from Northern California. I took Emma and her best friend to an afternoon screening of what had been described to me by someone who had seen it before it was released as "the worst movie of the year." After a buildup like that, I'm somewhat relieved to report that Herbie Fully Loaded, while undeniably no great shakes when compared to, say, Tokyo Story, or Nashville, or Citizen Kane, or even this multi-character chamber drama, is pretty solidly situated within the Disney Herbie canon several notches below the original 1969 hit The Love Bug and several notches above either the abysmal Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo or the nearly unwatchable Herbie Goes Bananas. Yes, it's every bit as good as Herbie Rides Again (which, by the way has a far more entertaining title in Germany). Matt Dillon, as evil NASCAR champion Trip Murphy, is no David Tomlinson or Keenan Wynn, and Michael Keaton, as star Lindsay Lohan's down-on-his-luck racing father, often has a look on his face that looks less like character immersion and more like he's wondering how he took the long tumble from Beetlejuice to Beetle Dad. But the movie is reasonably well paced and doesn't ladle on as many bad pop-rock songs over action montage sequences as I expected it would, and the big NASCAR finale is, if clipped a little short, still entertaining enough for the undemanding Herbie fan in my household.

As for Lindsay Lohan, who longs to burst out of exactly these kinds of roles (she does have a featured role in Robert Altman's upcoming adaptation of Garrison Keillor's A Prairie Home Companion), Ms. Tabloid does reasonably well coloring within the lines of her character here. There is an awful lot of Lohan stuffed into a parade of too-tiny T-shirts in scene after scene, which is one thing-- even Disney would have been unlikely to ask her to wear a loose-fitting burlap sack in order to avoid turning the cranks of lecherous dads who have tagged along to matinees with their kiddies. But, as my friend Andy rightly points out, things start getting a little uncomfortable when Lohan is poured into a low-cut mini-dress for a scene in which Dillon attempts to seduce her... into taking his NASCAR rocket for a ride. And as we sat through the end credits, I was very grateful for my toddler's uncomprehending ear as Lindsay crunched out some generic-sounding pop-rock twaddle in which she laid down the law to her boyfriend-- "I wanna come first!" Between this conspicuously inappropriate lyric and the whole digital breast reduction nonsense, the Disney marketing department has been, I suppose, relatively restrained in not coordinating some synergistic photo layout in ESPN magazine featuring Lohan languishing on top of Herbie's steaming hood, leisurely stripping off her racing gear. And that digital breast reduction float was just that-- nonsense. Seriously, if the x-and-o artistes did digitally diminish her curvaceosity to accentuate the girl-next-door-ishness of her character and she still fit into a T-shirt like that (at least at the time of shooting), then their tinkering has to rank as the most colossally over-hyped groundbreaking CGI wonder since Forrest Gump shook hands with John F. Kennedy. (I have since been told that the digital futzing was actually no more than a slight masking of the cleavage Lohan reveals in certain scenes to reduce the visuals, apparently, from lascivious to mildly arousing, news which makes the pre-release announcement even more of a tempest in a D-cup.)

RUBE GOLDBERG’S DEATH MACHINE, LEGOLAND AND THE GLORIES OF THE VISTA

Evan's flight from the north ended up running late, and by the time he and I made it home from the airport that night it was far too late to head out to a movie theater. So after we got the luxurious air mattress set up on the living room floor that would serve as his bed for the next six days, we cracked open a couple of Diet Pepsi Limes and he shook off his plane trip to the cackling rhythms of the Rube Goldberg death machine that is Final Destination 2. We both giggled and snorted and shivered in all the right places, and I went to bed happy that I'd converted another unsuspecting movie fan to this picture's ghastly pleasures, happy at the thought of spending a week watching movies with somebody who would actually want to stay up late with me after a evening flight to see somebody get spectacularly trisected by a airborne section of taut barbed wire.

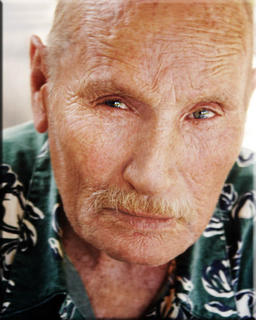

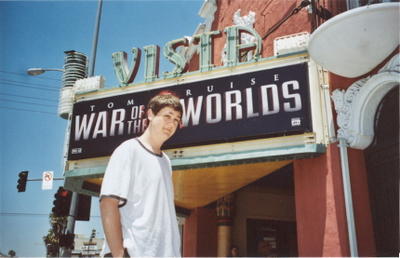

Patty, Evan, the girls and I spent Sunday in Legoland, just north of San Diego, so no movies that day. And Monday I took him to the glorious Vista Theater for a screening of Batman Begins. He was duly impressed with the decor of the recently remodeled auditorium while the lights were still up, and extremely impressed when the lights went down and the Vista showed off what I still believe to be the best combination of picture and sound in Los Angeles. Just seeing a movie in a genuine old single-screen movie palace with a real sense of history was an unusual treat for this movie-mad child of multiplexes, VCRs and DVD players, and he was suitably appreciative enough to get excited when I told him we'd likely be coming back to the Vista later in the week for opening day of one of the biggest summer blockbusters of them all.

AT THE DRIVE IN: SEXY ASSASSINS OUTPERFORM THE MEAN MACHINE

Tuesday night was drive-in night. One of the things that Evan’s mom insisted on before he came to visit was that I figure out a place to take him to see a drive-in movie—finally, a good excuse to get to get back out to one myself! The drive-in was a story in itself, and Evan, master of the deadpan reaction, was as enthusiastic about his new experience as I could have hoped. I too was thrilled about finding this little gem of a theater, considering that I had assumed all the good drive-ins in Southern California had dried up and blown away—hell, I assumed all of them, good and bad, had dried up and blown away. So I was, as the dark horse Oscar nominee inevitably says as he/she traipses up the red carpet, just happy to be there. And a good thing too, because the double feature we chose didn’t seem to hold much promise—when darkness finally fell, we would bear witness to Mr. and Mrs. Smith (not a remake of the Alfred Hitchcock screwball comedy starring Robert Montgomery and Carole Lombard) and The Longest Yard (definitely a remake of Robert Aldrich’s brutal and astringent 1974 prison comedy).

That calm, level-headed, absolutely not a bit reactionary curmudgeon Armond White, in the first review of many bad reviews I read of Mr. and Mrs. Smith, led off his piece with this:

“You don't have to be Osama bin Laden to think that only a horrible culture would produce an ‘entertainment’ like Mr. and Mrs. Smith. But when a bootleg of this facetious comedy does get satellite-projected to that crazy hermit in a Middle Eastern cave, he'll probably break into an ‘I told you so’ grin.”

And from the timber of the rest of what White has to say about this movie, underneath the subheading “Two Shallow Spies and Everything That’s Wrong With America,” who could be blamed for expecting the experience of the movie to be akin to washing down your popcorn with Jonestown Kool-aid or having the Charles Manson and company drop-in unexpectedly for late-evening coffee? Almost all of the other reviews I read in the wake of White’s diatribe were, if a little less sackcloth-and-ashes in their condemnation, then at least none-too-excited about the movie and far too eager to focus on the back story of the film’s torturous production and whether the alleged off-screen chemistry of stars Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie translated into on-screen fireworks, not exactly scintillating subjects for honest film criticism. As for White, since his initial review of the movie he has derided Bewitched as “after Mr. and Mrs. Smith, the second screwball catastrophe in a month,” and Don Roos’ Happy Endings as “2005’s most loathsome film so far (outstinking Mr. and Mrs. Smith and Crash).” (White is the writer who chided Americans for ignoring the pop pleasures of Torque by saying, among other hilarious things, “Only a humorless prig would be appalled by this.”) I can’t wait to find out how Wedding Crashers is so wretched as to justify not only bin Laden’s hatred of America but perhaps further action against its citizenry, and during his lecture White will surely find a way to bring up Mr. and Mrs. Smith yet again. This blockbuster comedy may no longer be the worst movie of 2005, but it remains, for White, a significant touchstone of evil.

Maybe it’s just my taste for touchstones of evil, but I settled in behind the wheel and almost immediately found Mr. and Mrs. Smith to be much less a laundry list of American (and Hollywood) decadence than a surprisingly deft, sharp satire of the middlebrow aftermath of romantic seduction housed inside a typically nonsensical Hollywood high concept. The film’s construct of personal observation inside oversized action holds up remarkably well, until the last third or so, when the explosive set pieces start to stretch out a bit too long and thin. The movie posits the absurd situation that John and Jane Smith, whose meet-cute relationship began under fire in a foreign country, are assassins for rival companies who have remained unaware of their spouses’ true vocation for six years. The calcification of their marriage into robotic routines and half-felt dialogues, and their attempts to solve the problem through counseling, coincides with the realization that each has been assigned to assassinate the other in the aftermath of a botched hit on an industrial spy. So Smith becomes a comedy of marital rebuff, struggle and reconciliation that plays itself out in literal/metaphorical gunfire and explosions, as the Smiths escalate the War of the Roses into total suburban apocalypse. Pitt and Jolie handle the subtler tensions of that flattened-out suburban existence, decorated at every turn by a fantastically imagined manse done up in fetishistic Crate and Barrel detail, tossing off the movie’s sometimes excessively loaded innuendo with panache and teasingly acrid humor. By the time the Smiths have decimated their house in trying to decimate each other, and then end up in an erotic clinch the likes of which they haven’t experienced since the early days of their courtship, the movie has made a believable connection between the playing out of aggressions and the reigniting of romantic passion within a relationship. It isn’t a therapeutic strategy you necessarily need to believe could be applied to real life, but within the screwball parameters the movie has set for itself, it works remarkably well, and the patterns of actual marital concerns are discernible amid the rubble and revving engines. The movie falls too much in love with Mr. and Mrs. Smith shooting themselves out from one sticky situation after another as the movie whizzes to its climax and unfortunately devolves into simple post-John Woo pyrotechnics. But until then Mr. and Mrs. Smith, with its perfectly beautiful stars (and Jolie really has never seemed so lustrously gorgeous on screen as she does here) standing in for Mr. and Mrs. Joe Married, works small wonders with a premise that at first glance seems tired and obvious at best, overbearing, snotty and sexist at worst. Osama bin Laden could probably care less, actually. Now, how do we get Armond White to calm down?

The less said about the evening’s second feature, the better. Adam Sandler has brought his laid-back (barely sentient) persona to bear on the remake of Robert Aldrich’s The Longest Yard, and the result is a reduction of the rating by a half-notch (R to PG-13), an escalation of homophobic humor, and a straight-across trade of the original movie’s nihilistic worldview for a cynical devaluation of just about all points of view, those derived from Tracy Keenan Wynn’s original screenplay, and those provided as thin padding in the “new” script by Sheldon Turner. All you really need to know about the new version of The Longest Yard is that the rough-and-tumble black prostitutes brought in to act as cheerleaders for Paul Crewe’s Mean Machine squad of inmate football players in the 1974 original have been replaced by black transvestite prisoners, objects of high comedy indeed, and all the better for our boys keeping a good, solid hold on that bar of soap in the shower. If that little bit of “updating” strikes you as riotously funny in itself, then by all means, don’t miss the new version of The Longest Yard, a movie singular in its ability to make me pine for that other Adam Sandler football movie. Rob (“You can doooooo eeet!”) Schneider shows up in the stands to get absolutely no laughs by recycling his peculiar catch phrase while cheering on the Mean Machine in this one too. And not only that, but we got to sit through a trailer for Deuce Bigalow, European Gigolo. After it was all said and done, I’ll be damned if that grotesque-looking sequel didn’t still look like it’d be better than what Sandler hath wrought this summer.

WAR OF THE WORLDS AND SPIELBERG'S TENDRILS OF BLOOD

We were back at the Vista the next day for the opening of Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (H..G. Wells goes unmentioned above the title), munching on sandwiches from the Vons across the street while standing in line about an hour and 15 minutes ahead of show time. It was a good opportunity for Evan to peruse the celebrities immortalized in cement in front of this theater, a rather more specialized crowd than the more famous collection in front of the Grauman’s Chinese. Here you’ll see signatures, handprints, lip prints and whatever other body part might make an impression from the likes of Ray Harryhausen, Ray Bradbury, Adrienne Barbeau (The Fog, in case you were wondering), Robert (Count Yorga) Quarry and the 30th-anniversary reunion of the cast of Night of Dark Shadows, the 1971 sequel to the first movie version of TV’s horror soap opera hit, House of Dark Shadows (1970). Handprint ceremonies are much more infrequent at the Vista than in front of the Chinese, where even Ryan Seacrest can rate a star or a wet block of concrete, but when they do happen it is cause for hollering and rejoicing in Genre Heaven, the epicenter of which, on those nights, could easily be mistaken for the Vista Theater.

As for hell, it is often joked that New Jersey is if not the underworld’s fair representation here on Earth, then at least a reasonable facsimile, a way station with plenty of ghastly offenses all its own with which to whet the terrors of the damned. But in War of the Worlds the vision of New Jersey as hell is realized as the world of the everyman under devastation by rampaging alien invaders whose deadly attack vehicles have laid buried under our major cities for centuries, awaiting the moment when their operators would beam down into them and bring them to fearsome life. There is the requisite calm before the storm: everyman protagonist Tom Cruise is a divorced father named Ray whose wife (Miranda Otto, consigned to bookend cameos), now pregnant and living in Boston with her new husband, drops off their two children, sullen teenaged boy Robbie (Justin Chatwin) who hates Ray for abandoning his family and his responsibilities, and precocious pre-teen Rachel (played by precocious pre-teen actress Dakota Fanning), for a weekend with Dad. The kids are exasperated to see Dad’s none-too-tidy apartment, but Rachel is willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. Robbie, however, makes a point to wear his Red Sox cap when Dad offers to play a friendly game of catch—Ray is, as it is implied everyone is in Jersey, a Yankees fan. (Have angry Mets fans have made a point of storming out of screenings in disgust during this scene?)

Dad gets a chance to prove his mettle, though, when a very creepy electrical storm hits town and one of those alien vehicles comes charging right up from under a church—so much for religious institutions when it comes to standing up to interstellar threat—initiating the devastation that will compel Ray to find it within his callous heart to become the dad he’s failed to be up till now and to reunite his kids with their mother in Massachusetts. For the first two-thirds, War of the Worlds is very scary and unsettling, and it seems that Spielberg has got his mojo going pretty strong, creating imagery-- those tendrils of blood snaking out over the deadened landscape-- and individual sequences that comprise some of the best filmmaking he’s done in years—the opening storm sequence and the initial appearance of the alien force are both shot through with the kind of dread, and the subsequent explosion of fear, the director conjured in that rippling glass of water just before the T-Rex appeared in Jurassic Park, only this time on a much grander scale, and infused with references, both direct and indirect, to the horror of 9/11. And an onslaught of panicked citizens overrunning a ferry, with horrific results, is staged with such fury and clarity that, despite the difference in the scales of the vehicles, it makes James Cameron’s sinking of the Titanic look like bathtub play.

(SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t seen War of the Worlds yet, or if you skipped that reading assignment back in junior high, be aware that for the rest of this review I will be assuming that you have or that you don’t care if key plot points are revealed to you ahead of time.)

Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp have gambled on the idea of revealing the invasion entirely from the point of view of Cruise’s character, hewing close to the original storytelling strategy of Wells’ narrative—which means never revealing more about the motives and methodology (beyond mass destruction) of the invaders than Ray himself ever discovers. This is a risky strategy, especially since Ray is a lower middle-class dockworker, not a scientist who could be used as a convenient device to create context for the alien presence or explain their ultimate failure. The movie generates much of its momentum from its episodic structure as Ray fights his way out of Jersey, trying to keep his son from running off to join up with the military to fight the aliens, trying to keep his daughter from being an eyewitness to too much horror, and trying to keep from being vaporized by or sucked inside one of the alien tripods.

Everything eventually settles down into an extended interlude in which Ray and Rachel take shelter in a basement along with a somewhat deranged survivalist type played by a wild-eyed Tim Robbins, who, it becomes clear, is as dangerous to their survival as the aliens themselves. It’s a scene that provides a much needed respite from the relentless action, but I also think that it’s here that the air starts leaking out of the movie and the weakness of Spielberg and Koepp’s storytelling tack begins to be revealed. Ray is eventually compelled to cover his daughter’s eyes and murder Robbins (behind a closed door) to keep him from pointlessly attacking the alien forces and revealing their whereabouts, but they are discovered nonetheless, and the movie, initially one man’s point of view of global apocalypse, becomes a movie about how global apocalypse affects one man. He couldn’t be bothered to provide them a decent meal before the horror began, and now he’s murdered to keep one of them from harm and will be forced into even more conventional heroics in order to reunite them with their mother in Boston. Unfortunately, Cruise is too much a look-at-me presence, so the movie’s shift in perspective is easily accommodated and encouraged not only by the movie’s refusal to elaborate on the events we’re witnessing, but also by the actor’s natural tendency toward narcissism. It’s hard to accept Cruise everyman-ness, no matter how much the movie insists on it, so it’s seems natural that we should be led to see the destruction of our planet as simply the impetus that gets Cruise to see the light re his familial responsibilities.

By choosing not to provide the scientific or military context more familiar from less ambitious science fiction epics, the movie can’t help but slide into this kind of narrative reductivism—it has nowhere else to go, and its adherence to Wells’ ending reinforces the reductivism too. Ray and Rachel finally do make it to a curiously undevastated Boston, where they are reunited with Ray’s ex-wife, her new husband and his parents (played distractingly by Gene Barry and Ann Robinson, stars of the 1956 George Pal movie version of Wells’ book) in one of those fairy-tale conclusions Spielberg is often fond of imposing on stories and situations that warrant far grimmer results. Even more unexpectedly, Ray and family realize that the attacks have just suddenly stopped; the alien ships are crashing and burning for no discernible reason. The movie pulls up short and the characters are presumably left to wonder just what the hell happened, but fortunately we have Morgan Freeman’s narration to tell us what they may never find out—that exposure to the most insignificant microbes, the building blocks of life on our planet and the bacteria to which we have built up millions of years of resistance as a species, have somehow proven toxic to these creatures and in a matter of days devastated their immune systems in much the same way as they have laid waste to much of our civilization.

Ironic, yes, but not exactly the stuff of which satisfying movie climaxes are made, and the matter-of-fact biology of the events got me wondering about those aliens and their supposed intelligence. One might suppose that the alien warriors wouldn’t have gotten a taste of those microbes until they were deposited in those subterranean sleeper cell vehicles via the very specifically directed lightning bolts of the film’s opening storm sequence and then emerged from the ground to begin their assault. But what of the reconnaissance squad, the exploratory forces that determined our planet worth invading and harvesting to begin with? Would not the aliens that initially engineered the planting of those vehicles been exposed to the same fast-acting biological defenses that proved so fatal to the aliens we do see? And if so, one would think that the inability to sustain life on a planet crawling with single-celled killers would be information that might be comported rather quickly to the main forces supporting the attack on Earth, thus circumventing the destruction before it ever had a chance to begin. Spielberg’s filmmaking is strong enough that many might not be bothered by this inconsistency, but it’s a hole in logic that, in retrospect, conjures up too many comparisons to M. Night Shamaylan’s asinine Signs, in which an ostensibly advanced race of murderous aliens decide to invade a planet which is three-quarters covered in a substance (water) that—whoops!—turns out to be kinda fatal to them.

Some have accused Spielberg of pornographic misappropriation of the horrors of 9/11 to bolster the effectiveness of what is essentially a fantastical representation of an attack with no pointed political context—in other words, a boogeymen-from-outer-space schlockfest. Well, even though I think of the new War of the Worlds as only a partial success, I think it’s a mistake to condemn it on such grounds. Doing so negates a long history of science fiction film that engages in the paranoia and devastation of the day to inform its narratives and provide potent ways of dealing with those realities. I’ll admit to some initial trepidation over some of the film’s more overt references to what New Yorkers experienced in the aftermath of those ghastly attacks nearly four years ago—the ash settling on survivors of the first assault, posters pleading for information about missing loved ones posted on walls and fences, and Rachel’s terrified inquiry to her dad as to the identity of the attackers—“Is it the terrorists?” Obviously the wounds of the disaster of the Pentagon and the World Trade Center are still fresh even to those of us who had no proximity at all to the epicenters of the attacks, and those wounds are what I credit for the ache in my gut as some of the film’s sequences unfolded and were revealed to be treading some very familiar, very turbulent psychological waters, as well as the insistent ambiguousness of my response to them even weeks later. It was all very powerful, but in this context I wasn’t sure what it all meant. And then I started remembering that science fiction and horror (and this War of the Worlds is often as much a horror film as it is sci-fi) have always been genres that have lent themselves well to filmmakers, and audiences, projecting their fears and societal concerns onto the narratives and wrestling with national traumas. As David Edelstein points out in a response to a fellow Slate writer who has condemned Spielberg for crass exploitation of the 9/11 tragedy, sometimes it is the movies that are best suited to give those feelings, those points of view, those reactions a structure, a format for concrete expression, and manages to remind us of a couple of good examples:

“A respectable body of critics—myself among them—consider (the original Godzilla) a haunting depiction, by the Japanese themselves, of the trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Farther afield, I can't think of a film that captures the social upheaval—racial and interfamilial—of the middle and late '60s as suggestively as Night of the Living Dead.”

Similarly, the three separate versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers-- Don Siegel’s 1956 version and the 1978 and 1994 remakes, courtesy of Philip Kaufman and Abel Ferrara—wrung fear of communism (or its inverse, fear of McCarthyism, depending on who you believe and, of course, your own political point of view), fear of the numbing pop psychological trends of the Me Decade, and fear of rampant militarism all out of the same basic story outline. And one could go on a long time pointing out examples of trepidation and distrust of what lay ahead on the new frontiers of science in any number of science fiction and horror films of the ‘50s, ‘60s and even into the ‘70s. If Edelstein’s article had shown up a little earlier than today, it might have been useful in helping me sort out the scramble of emotions that the imagery in Spielberg’s film churned up in my heart and mind. But it’s valuable also as a reminder that, whether you find the film a masterpiece, as Edelstein does, a brilliantly realized but honorably flawed experiment in narrative, as do I, or “the worst movie I’ve ever seen” (as one man muttered to my nephew and I upon bolting from the movie midway and encountering us as we entered another auditorium that same day), one thing seems unalterably true: Spielberg is not a carnival barker exploiting real-life misery by grafting it onto some candied sideshow of Hollywood-ized atrocities, and to accuse Spielberg of being a pornographer just seems reactionary and misguidedly moralistic. War of the Worlds is a sincere attempt to carry on in a way that science fiction has carried on almost since its beginnings. Whether it succeeds or fails as a work of art, it should be recognized as a seriously intended product of a nation’s fears, perhaps even of the dangers of a government, like a race of alien attackers, concocting rationales for invasion before all the deadly facts have been assembled— that is, a product of the times in which it was made.

(Amusingly, and somewhat convincingly, Andrew Sarris, writing in the New York Observer, posits a theory about Spielberg’s movie that, curiously, everyone else seems to have missed. Sarris writes:

”Ray barely has time to order take-out pizza for his boisterous brood before all hell breaks loose in the heavens and below the earth’s surface. And there, staring me in the face, was a glaring subtext that had been missed in all the reviews I’d read: While Rachel was a little darling (at least until she begins screaming like a banshee nonstop), Robbie was a pain in the neck from the word go. He seems to hate Ray for having left his two children behind after he got the divorce. The usually symbolic evidence is clear: While Ray is complacently wearing a New York Yankees cap, Robbie stands head-to-head with his father and defiantly sports a Boston Red Sox cap. So that’s what this updated version of War of the Worlds is at least partly about: the hard feelings that have lingered long after the Red Sox ended their ancient curse of futility by sweeping the Yankees out of the American League Championship (and a shot at the World Series) after the Yanks had won the first three games of the series and were leading late into the decisive fourth. If this proposed subtext seems more than a little farfetched, let us consider the literally laughable last shots of the movie. After much of New Jersey, Staten Island and upstate New York has been pulverized by the aliens, Ray and Rachel find their way to Boston, which apparently has been completely untouched by the invasion. Indeed, Boston seems to serve as a spiritual Shangri-La for Ray, his children and all the other survivors from the devastated domains of Yankee fandom.”)

THE RETURN OF PETER JACKSON

Far more tantalizing, for me, than witnessing Spielberg’s destruction fest (9/11 and baseball subtexts or no), was the unveiling of the first full-length trailer for his upcoming remake of King Kong. Predictably, fan boy sites began deciding as soon as they saw the trailer what to think of the movie, even though Jackson himself said that it was full of CGI shots that were not fully completed, and even though it’s patently absurd to decide on your opinion of a movie a full six months ahead of its release. It is one thing to get bad vibes about a movie based on what you see in a preview (after all, those vibes could end up being caused by the way the trailer itself is assembled, and the movie could either feel different or reveal other aspects that the trailer overlooked which might sway an opinion to the positive). It’s quite another develop ossified opinions about the work itself based on two minutes of clips. And it is quite another to have high hopes again about another spectacular Peter Jackson offering after having seen this trailer, which I now most definitely do have. The movie itself could turn out to be the year’s biggest disappointment—anything’s possible. But the effects and the grandeur and the atmosphere are all there in the trailer we saw, and I would be surprised if it wasn’t at least as good as the underrated (though admittedly tacky) 1976 version. I was also surprised, while watching the preview, to find myself reacting just as positively to the offbeat casting—Jack Black in the Robert Armstrong role, Adrian Brody as Bruce Cabot, and Naomi Watts in spot-on (though Panavision and full-color) recreations of familiar poses from 1933 in the part stamped forever by the gossamer presence of Fay Wray. Jackson has the ability, the passion and the love for the original that makes him the only person who could possibly bring off such a tricky project. The question that remains to be answered, that can only adequately be answered not in endless Internet diary excerpts and interviews, but by the film itself is, what compelled him to want to do it in the first place? Perhaps more so than any of the multitude of other remakes that have been unveiled or have yet to be unveiled in 2005, I expect that Jackson’s answer will itself be compelling and heartfelt, and just may translate into another transporting visual/aural amazement to add to his filmography, and to our benefit as moviegoers in search of an Event at last worthy of all of the hype.

LAND OF THE DEAD: APOCALYPSE CHOW!

I’ve admitted to the heresy before, and here is as good a place to admit to it again as any— While I count myself among those who recognize 1968’s Night of the Living Dead as a landmark work of social horror and one of the scariest films ever made, I think George A. Romero’s sequel, Dawn of the Dead, is an overlong, clunky and flabby pile-up of obvious alle-gory that gets driven into the ground and pulverized by its writer-director during the movie’s near two-and-a-half hour running time. The movie’s narrative metaphors and punk visual strategies get worked over and worked over until the meaning is just so much pulp, shredded like the innards of those bikers unfortunate enough to stumble upon that overrun shopping mall and think, for even a second, that their chrome and hot leather aggression could stand against the rampaging, flesh-eating horde. That shopping mall metaphor (“They’re drawn to it; it was a place that meant something in their lives”) is a good jumping-off point, but Romero hauls it out of the barn out early and rides it until it’s way wet, revealing few other tricks beyond numbing repetition in his bag—Boom! Get it? Boom boom! Get it? Boom boom boom! Get it??!! (Conversely, in last year’s stunning remake of Dawn, the shopping-mall-as-social center observation is just that—the place from which Zach Snyder’s far-superior movie spins off.) Romero’s Day of the Dead was, I thought, a big improvement, charting the profoundly frightening waters of the zombies’ further evolution from untethered force of evil toward domestication, or at least applied militarization (an idea also flirted with in the devastatingly funny conclusion of Shaun of the Dead). Romero was denied the budget to bring his movie to its obvious conclusion—zombie-fried apocalyptic war—but the movie still had a potency that its wildly overpraised predecessor lacked. Well, it’s taken 20 years and a Romero-less zombie revivification in the cinema made up of the likes of 28 Days Later, Shaun of the Dead and that 2004 Dawn remake (all films that are head and shoulders above Romero’s second zombie movie) to get Romero back out onto the playing field again, and what’s he’s come up with, Land of the Dead, finds the director continuing to mine his zombie horde for all the metaphorical weight it can bear, with the vein finally starting to come up empty.

Much is made of the zombie’s emerging intelligence, their empathy (for each other, that is—they still don’t much care that their meals don’t really care to be eaten), and their rudimentary ability to communicate—all signs that the director lights up like cheap neon in Vegas, the better not to miss. The zombies are just like us! Leaden line after leaden line drives the point home as we see the games human survivors play in order to perpetuate a financially (and ethnically) segregated, zombie-free society behind the glass walls of a high-rise community for the rich—a lame retread of the shopping mall motif in Dawn that gets little chance for its own satirical deconstruction—while the poor live down on the street and have to fight off the occasional zombie onslaught at the gates. Romero’s budget is probably the biggest he’s ever had, and the movie looks good, if not just a little too much like Escape from New York, with all that super-saturated blue standing in for night light. But the story’s wheels do nothing but spin right from the start, and what little momentum the narrative has is routinely dragged down by the actors—Simon Baker, Asia Argento, John Leguizamo, and Dennis Hopper, relatively restrained but still not very interesting as the corrupt Trump-esque owner of the high-rise—and Romero’s own adherence to the rules of the genre he created—the splatter must run on time, no matter the situation. Romero has largely failed to find vivid new uses for the up-to-the-minute CGI-enhanced gore techniques at his fingertips and, the occasional detached jaw notwithstanding, ends up creating the first zombie movie to flirt with genuine boredom. For the first time, the genre feels like a straitjacket for Romero rather than a freeing canvas on which to develop the kinds of ideas that can so easily blossom under such stringent narrative guidelines. So little is going on that the mind begins to wander to places it ought not go, such as, who keeps stocking the zombie-overrun supermarket shelves with fresh product for Hopper’s mercenaries to raid? If this is a society in collapse, obviously nobody told Procter & Gamble, Heinz, Nabisco or the truckers’ unions.

Land of the Dead is a serious movie—that is, it doesn’t let its roots in B-movie schlock deter it from trying to engage in some honest discourse with its audience about the state of the world (in the movie and outside the doors of the cineplex). But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s much good. Romero talks a much better movie, in the avalanche of interviews and feature stories written about this movie in the weeks before its release, than he has directed one this time around. I just hope that this movie’s artistic (and apparent financial) disappointment won’t end up meaning that we’re in for Romero making another protracted absence from filmmaking. On the other hand, when he does return, it might just be better if the director moved on and left the zombies where they are at the end of Land of the Dead-- lurching off over a city bridge into an uncertain future, the better for us to imagine our own next chapter to his increasingly depleted series.

HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE AND AN INAUSPICIOUS WRAP-UP

Evan and I ended our week together with a screening of Hayao Miyazaki head-spinningly beautiful Howl’s Moving Castle, which finds the director musing about age and ageism, sacrifice and, of course, the juggernaut of war (the movie was adapted from Diana Wynne Jones’ novel and conceived in the early days of George W.’s second “engagement” with Iraq). The movie is stuffed with imaginative flights, brilliantly semi-organic design (that castle is like a city all gummed up in a gigantic ball, held together with bailing wire, organs, piping and prayers, and made mobile by what look like gigantic chicken legs) and daring narrative leaps, parries and asides. Yet everything you need to follow the somewhat elliptical narrative (especially as regards the fate of the young prince whose disappearance has sparked the conflict) is there woven into Miyazaki’s heady design—you just have to have ears to hear it and eyes to see it. As mesmerizing as it all is, though, there’s nothing in Howl to equal that train ride with the masked spirit in Spirited Away, or the lovely cadences, spectacular vistas and telling observations of Kiki’s Delivery Service, or that midnight ride on the cat bus, or the treetop meeting with the titular My Neighbor Totoro. If anything, Howl’s narrative is only slightly disappointing in its straightforwardness—coming after the giddily free-associative Spirited Away, almost anything might seem so. It’s still the biggest visual treat you’ll see this year, but this time Miyazaki’s imagination is, if not grounded, then at least not soaring quite so high. It’s an unusually high standard that’s been set in order to consider a movie as wonderful as Howl’s Moving Castle a slight disappointment, but a small wonder that disappointment can still be so exciting.

The night before Evan flew back to McKinleyville, we decided to unwrap a DVD I picked up over the course of the week, that long-anticipated Anchor Bay edition of Race with the Devil. I sold it to him by breathlessly describing it as a movie about two vacationing couples who witness a satanic murder and spend the rest of the picture running from the killers, who now want to slice them up as well. What kid wouldn’t bite on that concept? (I certainly did when I saw it at age 15, the same age Evan is right now.) So we cranked up the DVD and settled in. The movie is every bit as clunky and fun as I remembered it, although it’s really amusing to see how age and nostalgia and faded memories end up embellishing favorite moments to the point where the ethereal reimagining of those moments almost always far surpasses the real thing. Seeing Race with the Devil again was a 90-minute exercise in reshuffling my memories back to reality—- not an unpleasant exercise, to be sure, and it’s certainly not like I’d inflated the movie to some sort of rarified status since last having seen it some 30 years ago. But it was refreshing, in the shadow of the many steroid-driven summer action movies we’d experienced that past week alone, to watch an unpretentious, small-scale drive-in classic, a movie unconcerned with blowing you away but fully engaged in the not-so-fine art of the cheaply budgeted cheap thrill. And with those cheap thrills Race with the Devil is loaded. By the time the movie sped, and lurched, to its trendily grim denouement, things had grown awfully quiet on Evan’s end of the couch. The ring of fire surrounded the ill-fated Winnebago containing our quartet of whining witnesses for the last time, and the very brief credit sequence rolled, unimpressed by the cackling Satanists who have apparently reigned triumphant. There was a moment of silence after the final frame, and then Evan turned to me and said, “Is that it?”

Yep, that was it. The curtain on our week of summer cinema madness had wrung down on a note of a gulf in generational experience that would probably never be spanned. How could a low-rent thriller like Race with the Devil ever compete for the attention of a movie-going generation for whom apparently even Michael Bay’s The Island, if early box-office receipts are any indication, is not even enough of a sensory-overload temptation? But this is a question best left to the academics. The bottom line is, it was a lot of fun having my movie-mad nephew around for a week to show the old fart what movie madness really looks like. Evan, I love you. It was wonderful to have you visit. Our floor and air mattress is yours any time you want it.

(* Evan has returned to the relative calm of Northern California, and I have, since I started writing this article two weeks ago, been lucky enough to see three movies in the theater, all of them terrific, two of them masterpieces, one of them one of the best movies I’ve ever seen, and none of them a THX-enhanced 6.1 Surround Sound spectacle of aural and visual bombardment. I will write, briefly, or perhaps not so briefly-- stop giggling out there; you know who you are-- on all of them in the coming week. Movie madness is fine, but the kind of emotion these three movies generate is more like the real thing—- it’s movie love.)