When

I was 11 years old, The French Connection came out and joined a list of

pictures I was too young to see (Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs, Dirty Harry, Shaft)

but would obsess over anyway. I even read the book, which somehow was okay with

my parents because, I guess, it wasn’t rated R. I saw my first R-rated movie, Dirty

Harry, later that year, but I never saw TFC until I was in college, and

though it was among the first cassettes I ever bought for my new Betamax in

1982, once I finally did see it William Friedkin’s movie never lived up to my

heightened expectations. Seeing it again last month for the first time in years

only confirmed that, its landmark car chase excepted, I think of The French

Connection as a fairly routine, relentless cop thriller that, despite Gene

Hackman’s Oscar-winning performance, is hardly the best of its kind.

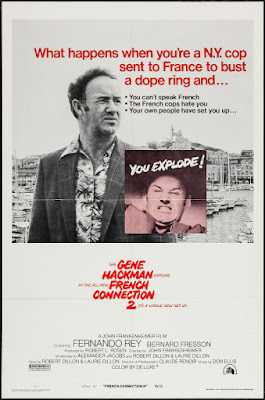

In fact, I’d only ever “seen” the movie in MAD magazine (“WHAT’S THE

CONNECTION?”) before I saw its sequel, French Connection II, at my

hometown movie palace, the Alger Theater, sometime in late 1975. I was

determined to love it, and I did like it a lot, though I remember thinking that

it didn’t feel at all like what I expected its predecessor might. In fact, this

would be the first of two sequels made from William Friedkin-directed megahits,

both of which would stray from the path of simply ghosting the template of the

original, a strategy that would not exactly endear either film to audiences or

critics. The sequel John Frankenheimer made to TFC is certainly not an admirable

oddity like Exorcist II: The Heretic, nor is it, like that film, a daring

artistic failure, but it must have certainly frustrated those who came to

theaters expecting their pulses to be pounded in the manner of the original

film.

Whereas

Popeye Doyle (and Hackman) by nature dominated the grim, burnt-out NYC milieu

of the first film, FCII transplants the detective to Marseilles, where his

overt racial bigotry can be directed exclusively, and in classic

really-ugly-American fashion, toward his French counterparts, and where the

movie can monitor Doyle’s fury at being brought over to ostensibly pursue Frog

One (Fernando Rey, reprising his role as drug kingpin Alain Charnier), only to

realize he’s being used as bait to lure the criminal into position to be grabbed

by the local police force.

But

Frankenheimer and screenwriters Alexander Jacobs, Robert Dillon and Laurie

Dillon, doggedly, some might even say perversely refuse to follow in Friedkin’s

footsteps. FCII is mapped out and directed as if the location (shot evocatively

by Claude Renoir) seeped into their bones— it feels more like an arty policier

that might have been made by any number of French directors of the time, its

concerns much more in locating the core of Doyle’s blackened heart than in

replicating the gritty, nihilistic thrills of Friedkin’s movie. One of the true

strengths of FCII is how it conveys Doyle’s sense of abandonment, his lack of

any real French connection, how he feels adrift in a culture, and more

precisely a policing culture, that he doesn’t understand or respect— to that

end, the movie provides no subtitles for its extensive French dialogue; like

Doyle, the audience is left to fend for itself and extract meaning from

context, observation and multiple conversations that lead nowhere.

Hackman

may have won his first Oscar for the original film, but this is the far more

rich, interesting, compelling performance. The actor courts our empathy at

being lost in a language and society he doesn’t comprehend, but he’s no less

blusteringly self-righteous for that; he makes a crude art of alienation,

because he can’t allow himself to believe that any other method than his own

could possibly be effective. Beyond all that, however, the filmmakers allow

Hackman to dominate the center of the film in an entirely unexpected way— about

45 minutes in, Doyle is nabbed by Charnier’s thugs and, in an attempt to rid

themselves of their American albatross, they string him out on the heroin

they’re trafficking and then, when he’s entirely dependent, toss him back into

the street. What follows is a long, harrowing, and strangely moving section in

which Doyle, with the help of the French detective (Bernard Fresson) he refers

to more as “Asshole” than by his actual name, agonizes through narcotic

withdrawal on his way back toward the world and his now-elevated fury over

Charnier and the way he has been used to tease the kingpin out into the open.

Perversely,

or perhaps daringly, Frankenheimer and company have structured this section of

the movie to be their stand-in for the prolonged car chase which is probably

one of the only things people remember from the first movie. It is the film’s

raison d’etre, its meaning, the polluted blood coursing through FCII, and it

alters the perspective of the entire enterprise, including Doyle’s own sense of

outrage and refusal to heed any precaution or safety in seeing his own personal

mission to its end. It’s a gutsy, not entirely rational response to the mission

of following up a well-respected Oscar-winning thriller, which is in its way,

like Doyle’s, its own personal mission, and it turns what could have been a

rote regurgitation designed to sell popcorn

into something akin to a living, breathing creation, something made to respond

to the world instead of just make furious noise within it.

FCII ends

on a more definitive note than its closure-denying predecessor, but even in

that definition Frankenheimer finds room to undercut any true sense that Doyle

has finally completed his task. With an abrupt cut to end credits just before

we can process the resolution we seem to have witnessed, we get Doyle’s shot at

some measure of release, of payback, alongside the simultaneous realization

after the cut that things are still moving on the water, that we can never

really be sure if the prey is down or simply delayed in the game.

At a

time when a tidal wave trend toward commodifying sequels was only just

beginning, French Connection II, in a way perhaps more modest but

spiritually akin to Coppola’s work in expanding the tale of the Corleone family

the previous year, proved that it is possible to honor origins by mining

character more than simply committing a hollow act of imitation. It may not be

particularly well remembered in the shadow of its 1971 predecessor, but it

should be.

***********************************