The Internet is a wonderful thing, don’t get me wrong, but there is something about me, rooted, undoubtedly, in my predilection for cave drawings, that resists the idea of going all electronic. It isn’t necessarily that electronic media are more impermanent than print—the last I checked, books and paper can burn or otherwise be destroyed with about as much effort as it takes to hit a “delete” key. Much has been made of the imminent death of print newspapers and the emergence of e-book technology like the

Amazon Kindle, in which entire books can be downloaded onto a keen little device that turns the page for you and can even read the book

to you, and there is an undeniable appeal to this kind of cultural mutation. I don’t think that newspapers will ever go away, but I do think that newspapers will continue to evolve (devolve?) to become more like their online incarnations. And one thing that does get deemphasized in that process, alongside the increasing shallowness of the format and the coverage, is the reader’s physical connection and interaction with the printed material. It comes in that physical engagement—the immersion into a forest of bookcases looking for a particular volume, the feel of the paper or the newsprint as it folds and turns in the hand, the idea of words as tangible creations on a tangible medium, the portability of that medium—curling up in the breakfast nook on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and your Kindle just doesn’t seem the same--

isn’t the same—as cracking open the Sunday paper and laying it across the table. And what Googling an author or subject offers in terms of immediate convenience and ease of facilitating research is unrelated to the satisfaction one can feel at searching through that forest of bookcases and gathering the information the way a hunter might have gathered food for his family’s dinner.

For film lovers, one of the great developments of the Internet age has undoubtedly been the emergence of the Internet Movie Database, or

IMDb, as a primary research tool. I began my familiarity with IMDb back around 1995, some five years or so after the site’s initial launch. I was working on creating the closed-captioning for the sprawling documentary

A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies. We were not provided any research or script materials for this project, as was typical when working on a feature film, because the film, as we who were editing the captioning would soon discover, was composed primarily of clips from seemingly hundreds of films from Hollywood’s classic era. And when we got into the meat of the movie it became clear that we would need some way to access verified, complete and correct listing for the names of characters for each movie excerpted, as each clip would be referring to names and places within the world of the movie from which it was taken. Neither I nor anyone I worked with back then was in any way Internet savvy, and in fact only one computer in the entire office had access to it. But somehow we stumbled across the IMDb, and even in its relatively infancy it proved to be a godsend for our purposes. In addition to all the other mighty uses to which it has been put (as well as some relatively trivial ones), the existence of IMDb has virtually eliminated the occurrence of that maddening syndrome in which you are watching a movie and say to yourself, “I know I’ve seen that actor somewhere before, but I can’t think of where and it’s driving me crazy.” Now, if you can’t, as I couldn’t this past weekend, think of where I’d seen child actress AnnaSophia Robb before encountering her in

Race to Witch Mountain, all you have to do is click on her name on IMDb for a full list of her credits and start scouring. (The answer to my particular query? Tim Burton’s version of

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, where Ms. Robb was a juicily effective Violet Beauregarde, the girl destined to become a blueberry.)

Film fans younger than me, some of whom even read the words Your Humble Old Fart puts together on this site, would likely be hard-pressed to imagine a world without a convenient research juggernaut like IMDb. It has become the go-to spot in the virtual world (though not always perfectly infallible) for information on just about any movie ever released, dare I say, in the history of movies. But listen, you young whippersnappers—there was a day, before IMDb debuted in 1990, when film writers, researchers and fans had to actually consult a

library, either the public variety or one in their own home, to dig up the kind of information that is available instantly at the push of the correct sequence of keys on a computer nowadays. Some of my fondest memories, before all the various light-speed developments of this new information age, come from thinking about digging through library shelves and claustrophobic used bookstores looking for old, venerated or as-yet-unfamiliar texts on film criticism and history, books that would be used to add yet another brick to the construct of my sensibility as a student of the history and currency of the movies. As much as I loved searching those library shelves, the used bookstores were even more exciting, because if I found something grand or unusual or essential there, I could, if I had the cold, hard cash, take it home and make it a part of

my library.

Back in the early ‘70s, when I was just a pup of 12 or 13, I stumbled upon an ad in a movie magazine (probably something like

Modern Screen or

Photoplay) for a book club called the Movie & Entertainment Book Club. It was set up exactly like other book clubs of the time, like the Book of the Month Club, only this one would feature a monthly selection in the field of film or TV that would be sent to you automatically if you didn’t return the club card by a certain date. Of course you had to order a set of three or four books as your initial purchase (at a reduced rate, something like “Four books for $4.00!”). This was not an offer I could possibly resist, and with some cajoling at my mother’s heel she eventually assented to my joining the ranks. The first books I got were William K. Everson’s

The Bad Guys: A Pictorial History of the Movie Villain, Richard Bojarski and Kenneth Beale’s

The Films of Boris Karloff,

John Baxter’s

Sixty Years of Hollywood and a little paperback volume entitled

Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies, the very first incarnation, published in 1969, of what would eventually become one of the most popular movie guides ever published. The Maltin volume I had bought was already at the time three or four years out of date (the next edition wouldn’t be published until 1974), but I gobbled it up anyway, using it as a touchstone to become familiar with names and titles of movies that heretofore had existed for me only on the periphery—if they weren’t mentioned somehow in

Famous Monsters of Filmland

(and, incredibly, a lot of them were, even if they weren’t specifically horror or science fiction films), then I probably didn’t know much about them. So Leonard Maltin and his staff ended up being, along with Forrest J. Ackerman, some of my very first film teachers, a status probably held for thousands upon thousands of like-minded filmheads who grew up in the early ‘70s. These four books were the very beginning of my own library, the first four books about the movies that I ever owned.

But the Movie & Entertainment Book Club, which was instrumental in getting that library started, had an even more important ace up its sleeve in terms of the development of my cinematic interest. His name was

John Willis. A naval officer in World War II who served in the South Pacific, Willis was also a veteran of the New York Public School System, where he taught English for 20 years, as well as a member of the Actors Equity Association for over 50 years. (He currently, at age 92, resides in New York City.) These were all admirable achievements, to be sure, but for me, a certifiable movie nut growing up in an isolated desert town in Southeastern Oregon, at least 100 miles away in any given direction from any relatively current movie culture, John Willis was a beacon, a compiler of evidence testifying to the vitality of the world of film that stretched far beyond the printed monthly show calendar for my local movie theater. I became aware of Mr. Willis about two or three months into my membership with the M&EBC when there came an offer for the current month’s selection, a volume entitled

Screen World, subtitled “John Willis’ 1974 Film Annual,” which just happened to be the 25th anniversary edition of the book. I pored over the information on the order card, which told me just enough to get me curious—the book was a collection of information about all the movies released in the year previous to its publication date, meaning that the 1974 edition was all about the year 1973. It promised information on every domestic and domestically released film to see screen time in 1973, as well as over a thousand photographs, cast and crew lists and other statistics for each film, the year’s obituaries, Academy Award winners and other features. It all sounded far too tantalizing to resist and so, whether I intentionally opted not to return the card or it somehow got “lost” (given the size of my allowance back then, it was probably the second scenario), John Willis’ 1974 edition of

Screen World was soon on its way to my mailbox.

When it finally arrived in my mailbox,

Screen World did not disappoint. Beginning with a two-page pictorial dedication to Joan Crawford, the book introduced its main section on 1973 releases with another two-page photo spread, ranking the top box office stars of 1973. Not surprising, Clint Eastwood held the number-one spot, fresh off of

Dirty Harry, Play Misty for Me and his 1973 release

High Plains Drifter. The rest of the top 10 in descending order: Ryan O’Neal, Steve McQueen, Burt Reynolds, Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, Paul Newman, Charles Bronson, John Wayne and Marlon Brando. But the list doesn’t stop there. It goes all the way to 25, with some pretty fascinating stops along the way. The book never delineates the criterion for these box office rankings (most likely stats culled from

Variety or

The Hollywood Reporter), but it is amusing/amazing to think that we once lived in a world where the number 12-ranked box office movie star was Liza Minnelli.

Apparently, according to this document, people also used to pay to see great character actors in lead roles (Walter Matthau, #15, George C. Scott, #16). What in all likelihood should have been a grave marker—Roger Moore ranked at #13—turned out to be a flashpoint of apparently infinite regeneration. And as if there were needed any further proof that 2009 is not 1973, when I cracked open the book again recently it was revealed that the 19th most popular movie star of the year was Dyan Cannon. The rankings go all the way to number 25 (Dustin Hoffman, who once might reasonably have expected to have been sitting a bit higher), but on the page there is room for three more photographs, so photographs of three more actors there are.

These photos, however, are curiously unranked. We can only assume, then, that rather than just occupying space as filler, these actors continued the ranking down the number line. Therefore, the 28th most popular star of the year must have been Joanne Woodward, number-27 status was held by Sidney Poitier, and sitting in the number-26 spot… Eileen Heckart, Oscar winner for best supporting actress in 1972 for

Butterflies are Free who, according to

Screen World, did not appear in a movie in 1973. (

Butterflies opened in July 1972, so it must have had incredible legs!)

The book then moves on to the meat of the matter, the list of all the domestic and foreign films to have played in the United States during the calendar year under examination. The first movie listed,

Save the Tiger, gets a two-page spread, given over to many stills of Jack Lemmon in distress, a couple of Jack Gilford looking somewhat morose, and even one of Lemmon encountering Lara Parker and Janina Fischer in their provocative undies, topped off by a complete cast list, credits for the most of the top-end creative artists behind the camera, and even some technical specs (100 minutes; in Movielab color). Also listed is the month of the movie’s release (January), which establishes the chronological template for the rest of the book. (I always wished that the book would have been date specific here, but that’s a fairly minor complaint, given the bounty of information available.)

Screen World did not offer opinions or any other rankings about the films themselves—that was Maltin territory. For Willis, it was a matter of compiling the evidence of the film’s existence in the marketplace and the facts regarding who made it. For me, discovering the book in 1974, it was about using that information, and those photographs, to vicariously immerse myself in the ambience of the movie when the movie itself was often not available to me, either because I was too young to see it or, more likely, because it would never make it to my hometown movie screen. Therefore, I would spend hours staring at stills, cast and technical credits for movies like

Shamus, Payday, Godspell, The Long Goodbye, Slither, Book of Numbers, Scarecrow, The Mack, Super Fly T.N.T. and countless others, familiarizing myself with the names of the actors in these films, matching their names to the faces of the ones who appeared in the stills, and soaking myself in movies to which I would otherwise never come closer than the Sunday movie page in the big-city Portland

Oregonian.

I was recently thumbing through this 1974 edition over lunch, allowing myself the kind of luxury that I once took for granted to pore over the minutiae of some of the first few pages of entries. The books, at least the editions from the ‘70s and ‘80s that I became most familiar with, were not particularly well put together. There were the occasional typos, and the photos themselves, laid out rather perfunctorily, were not often clearly or otherwise well-reproduced. But I didn’t care then, and I don’t care much now. It didn’t take long to become lost in that very specific kind of

Screen World-inspired daze of information gathering. Not that any of this really matters, but for example, I’d forgotten that

The Train Robbers was directed by Burt Kennedy, that it was the last film photographed by William Clothier, who shot

Seven Men from Now, Merrill’s Marauders and

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and that Ricardo Montalban had a small role in it. But there it is in the first few pages of the 1974 edition. And just look at the cast for Disney’s

The World’s Greatest Athlete-- in addition to the leads John Amos, Jan-Michael Vincent and Tim Conway, look for cameos from Don Pedro Colley, Liam Dunn, Vito Scotti, Howard Cosell, Ivor Francis, Leon Askin, Frank Gifford, Jim McKay, Bud Palmer, Clarence Muse and a seeming ton of others. Turn the page and there’s a reminder that Phil Karlson directed

Walking Tall. Look, there a picture of Ahna Capri sitting in car with Rip Torn in Daryl Duke’s

Payday. (In 1974 I was far more fascinated by Capri than the oddly named R.T., because she was the villainess in

Enter the Dragon.)

Turn the page—Oh, my God, that’s Victor Garber in

Godspell. And a closer examination of the stills offers a reminder that Lynne Thigpen, the radio voice (and the lips, oh, the lips) that provided A.M.-frequency guidance to the bangers in pursuit of

The Warriors, was also a member of that movie’s cast. The stills made strange movies like

Slither and

Book of Numbers look more fascinating (and speaking of

Book of Numbers, there’s a pre-

Miami Vice Philip Thomas, sans the Michael, in a lead role). And sometimes those still revealed tantalizing sexual or violent elements that ever spurred on the imagination of an eager 14-year-old boy—there’s surprisingly graphic evidence of agony in one or two stills featured for

Scarecrow, and pictures that highlighted the sexual elements (however meager and twisted they might have actually been) of movies as disparate as

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Electra Glide in Blue, The Mack and

Heavy Traffic that made me definitely want to see more.

But for me perhaps the real glory of John Willis’

Screen World, this volume and every subsequent one I eventually added to my shelves, was the fact that the listings were not limited to the high-profile American pictures. About 100 pages in, the book would always turn to a section devoted to stills and technical/cast credits for scores of low-budget exploitation films and other under-the-radar mainstream releases. In the 1974 edition alone I learned of the existence of movies like

Sugar Cookies, an X-rated effort from producer Lloyd Kaufman (the accompanying picture shows Mary Woronov hovering lecherously over a nude Audrey Hepburn look-alike); Ferd and Beverly Sebastian’s

The Hitchhikers starring Misty Rowe;

Lolly Madonna XXX-- despite its title, a very violent (and PG-rated) story of a gory feud between moonshiners starring Rod Steiger, Season Hubley and Jeff Bridges, directed by Richard Sarafian;

The Baby, a psychological freak show directed by Ted Post and starring Anjanette Comer and Ruth Roman; and literally hundreds of others.

Many of these titles, helped, of course, by the lurid and somewhat arbitrary pictures Willis used to choose to include along with the titles, helped me to become obsessed with finding out more about them, tracking them down, and of course learning about the people who made movies like these, filmmakers and actors unlikely to ever get a think piece devoted to them in the Sunday papers and movie magazines I grew up reading. Similarly, the giant sections devoted to films from other countries released in the United States during the year under examination was always an exotic treat, and seeing full-page spreads devoted to movies like

Playtime, Deaf Smith and Johnny Ears, Day for Night, Late Autumn, Triple Echo, Don’t Look Now, Innocent Bystanders, Twitch of the Death Nerve, Trinity is Still My Name!, Ludwig and

Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me, to name only a very few, spurred me on to familiarity with many names from multiples genres of international cinema. The examination of these pages also helped to erode the defenses of a country boy who needed to know that there was more to the movies than just what Hollywood had to offer and who was scared to death of what some of those movies might hold in store.

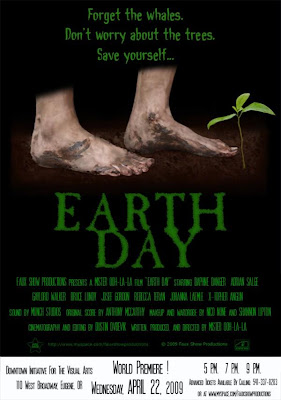

Finally, in addition to the obligatory sections on Academy Award winners from the previous year and the “Promising Newcomers of 19—“ section (see image below), my friend Bruce and I used to particularly love the section devoted to the year’s obituaries, which featured short write-ups on the luminaries who had recently passed away, and also the “Biographical Data” section which, assuming the information supplied to Willis by the stars’ publicists was correct, provided endless fodder for a little parlor game we often played during stretches of boredom in between studying for college classes in which we would try to guess the age of random celebrities pulled out of Willis’ book. Pride of accuracy was the only prize the winner ever got, and I don’t recall if it was ever documented just who did better in these contests on a regular basis. All I know is that we were both often able to zero in on the ages of the likes of Polly Bergen, Eddie Bracken, Teri Garr and Cliff Gorman, usually within a year or so on one side or the other, but sometimes hitting the target with the kind of laser precision that I seemed never to be able to duplicate when it came to things that really mattered, like school work or social graces.

Esther Anderson starred with Sidney Poitier in the movie he directed in 1973 entitled A Warm December.

Esther Anderson starred with Sidney Poitier in the movie he directed in 1973 entitled A Warm December.

It ought to be ridiculously clear by now that I loved the John Willis

Screen World series perhaps beyond reason, certainly more than any other books I had which managed not to offer any real point of view on its subject. Theirs was a true screen

world in which to get lost, and I frequently did. After that initial purchase from the M&EBC, for as long as I kept my club membership I made sure to order each annual edition of the book, editions which were always less expensive than they would have been had I purchased them off the shelf (and it occurs to me that during the time I was purchasing them I never entered a bookstore in which a new copy was available for purchase on a shelf). I kept up this affair with Willis’ books for about 12 years or so. By 1986 either my interest in the book club, or the book club itself (I can’t remember which) dried up altogether, and with movies like

Ordinary People, Terms of Endearment, Gandhi and

Out of Africa making their cultural mark on the Oscars, and crap like

Footloose, Flashdance, The Secret of My Success and

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off clogging up multiplexes, the ‘80s weren’t pitching much woo my way and I began to lose interest in keep track of them in that specifically

Screen World amount of detail. The last edition I bought was the 1986 edition. From then on I had enough tools of observation in my bag to navigate without the assistance of Mr. Willis, and though my

Screen World volumes remained dear to me, books I would revisit frequently, I had long since learned the value of reading the actual criticism found in books by Pauline Kael,

Andrew Sarris and within the pages of

The Village Voice and magazines like

Take One, Films in Review and, of course,

Film Comment. I still loved the books, but

Screen World no longer seemed as urgent to me, probably because the general trend of films during this decade did not itself seem urgent. I needed a critical voice to help me develop my own arguments and steer me through the dross in search of gems that could offset the depression generated by the bulk of what was available to me at the time.

Screen World’s overview had to, necessarily, yield to points of view.

When I moved to Los Angeles I spent a lot of time luxuriating in all the movies, both old and new, that were suddenly available to me, and a lot of time coming to understand that, unlike in Oregon, where the amount of screens that limited what I could see assured that it was possible to see just about

everything that came through town, my life as a moviegoer in Los Angeles was going to be defined, to some degree, anyway, by learning to be a bit more discriminating. Suddenly it was not possible to see everything that came through town, and as I became more and more well-adjusted this idea didn’t seem to be so bedrock horrifying to me as it once was. A key factor in my journey toward that adjustment was my meeting the woman who would eventually become my wife. The meeting was arranged—I was too socially inept or otherwise frightened to have ever navigated the seas of singledom with any success. But it was done with great sensitivity to the fact that this woman and I would never see eye to eye on everything, but in the realm of artistic appreciation—music, theater, literature, film—we had a lot of common ground. The very first movie we saw together was the opening night of Terry Gilliam’s

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, and though I liked it much more than she did there was a mutual appreciation of Gilliam’s sensibility and his effort, if not the quality of the final product, over which we could bond.

I remember some uncomfortable moments—we got into a pretty big scraper over

Nashville on an early date, she being of the mind that Altman was a talented but overly manipulative presence as a director. She hated his use of the zoom to punctuate thoughts or direct attention through a crowd, and she found him often fatally condescending. That night we sat in a Denny’s on the I-5 on our way home from a Warren Zevon concert arguing over my favorite movie of all time, and I wondered if this relationship was fated to ever go anywhere. (Later, the argument continued even more vehemently when we saw

Vincent and Theo together.) But more often than not we shared a sense of humor and general agreement on what film could be, and what it should be, that drew us ever closer. (Early on, my greatest miscalculations in this arena were misreading of just how far that connection would stretch. With some enthusiasm I lent her my Betamax copy of

Brewster McCloud—Altman again!— to watch while I went out of town on a trip, only to learn that she watched it with a friend and mocked it until they could take it no more and finally shut it off. And then there was the time Bruce and I invited her and her best friend over for dinner and a screening of

Basket Case, which we assured them was a ton of fun… The connection apparently did not extend to Times Square grindhouse fare.)

My future wife and I began spending a lot of time together around 1989, and my campaign to win her over took two more years, until one night in April 1991, on a beach near Malibu—well, it seems there is a limit even to my penchant for immodesty. Just know that we spent every weekend, and many evenings during the week, getting to know each other. Dating, in other words. And back in the late ‘80s when I was a swinging—or rather, dangling—bachelor, I had even less money than I do now, and certainly not enough to properly devote to affairs of the heart and other luxuries in the pursuit of love. Yet here I was, heading out every Saturday afternoon, whispering a silent prayer at the ATM that money would actually come out when I inserted my card and pressed the right sequence of buttons so I could cook dinner for her, or take her out for dinner and a movie, or a show, or whatever. Sometimes, when I knew damn well that the ATM wouldn’t work, it meant writing bad checks on a dwindling bank account in order to cover the grocery bill at Ralph’s for the dinner I would cook in my crumbly little one-bedroom apartment, a personal touch I hoped would somehow chip away just a little more of her resistance to my charms.

During my most desperate times I was not above selling some of my CDs and even books to local used record and bookstores in order to come up with dating cash. And one Saturday, sometime in 1990, if I’m not mistaken, engulfed by bills and not making nearly enough at my graveyard shift job to exist at a level that didn’t in one way or another embarrass me in front of friends and family, Patty and I had made plans to spend some time together. I knew that I didn’t have the means to take her out the way I knew I wanted to, and I wanted to mask from her the fact that I was as poor as house dust for as long as I could—God forbid she have all the facts and use them to decide one way or the other (probably the other) as to the wisdom of spending much more time with me. I’d already sold just about every CD, essential and nonessential, that I had, as well as every book that held any value for me or anyone else, so my meager resources were extra meager. There was, however, something on my shelf that might fetch enough pretty pennies to get us through the weekend, and I was committed enough to pursuing the relationship that, after only a minor session of hand-wringing, hemming and/or hawing, I swallowed hard and decided that, in order to get the money to take Patty out on the town that night, I would gather up my 12 years of John Willis’

Screen World volumes off the shelf and see if anyone in town was willing to pay me for them.

I found a buyer with little trouble. What trouble there was lay in the pittance he was willing to offer me in return for them. But I was desperate, and that afternoon, with our prearranged date time fast approaching, I accepted something like $5.00 a book for the entire 12-book set. Let’s see now… $5.00 times 12 books… that’s $60. And life in Los Angeles in 1990 was still cheap enough that an enterprising young man could take his date out (with, perhaps, just a little nudge from American Express) for what might pass for a nice evening out armed with $60 in cold cash. As I walked home I could hardly believe that I’d parted with those books, and for so little. But the fact that I did served to me as evidence that I really did love and care for this woman, and so I tried not to think of it again and certainly never held it against her, even on my crankiest, most self-righteously angry day. I never said a word to her about it until a couple of years after we were married in 1993. I don’t remember how the subject even came up, but I’m pretty sure it wasn’t in an argument (she can clarify this if necessary). I told her about the sale of the books and she was mortified. She knew, from the time she spent getting familiar with my bookshelves when we first starting going out, that the Willis books were very important to me, and as I suspected she would she immediately began a campaign of guilt directed toward herself over the fact that I’d used them to finance one of our dates. I appreciated that she took the gesture so seriously, but I honestly never intended that she find out for this very reason—I was living just fine without the books, and though I never conceptualized it as such, I felt then, as I feel now, that I came off with the better end of the trade-off.

Manager Noriyaki Nakano, left, and owner Jerome Joseph in Brand Books. (Photo by Ricardo DeAratanha)

Manager Noriyaki Nakano, left, and owner Jerome Joseph in Brand Books. (Photo by Ricardo DeAratanha)Even so, she spent the next few years paying special attention to the film section whenever we’d go into used bookstores in the hopes of finding a few volumes of

Screen World that she could put back into my library. She had little luck, until sometime in the late ‘90s when we found several volumes from the early to mid ‘70s in a nice shop called

Brand Books on Brand Boulevard in Glendale. The price was steep-- $17 each—so I had to limit myself to two. It was only when I got them home that I realized the books had been severely mutilated or otherwise bowdlerized for stills. With great disappointment I took them back to the store and showed them to the owner, Jerome Joseph, who was suitably horrified. Of the volumes still on his shelf there were two—1976 and the original year my Willis obsession began, 1974—that had somehow escaped the scissors. I grabbed them as replacements, and for the last 10 or 11 years they have stood as the only representation of my once–proud collection. In the ensuing years every time I’ve toyed with the idea of adding to my collection I’ve run up against the reality that, in the age of eBay, even just “very good” quality editions of these books begin selling at around $25 each. I recently ran into a copy on the 1974 edition online that was going for $75. Without those book club member discounts afforded me by the Movie & Entertainment Book Club, the

Screen World market had become officially too rich for my wallet.

Jump cut to the year 2009. The Saturday before last, just as we do a couple of Saturdays every month, the missus and I took our daughters to visit the Glendale Public Library to pay overdue fines (it happens) and check out new goodies. While she herds them up to the children’s library and gets the selection process underway, I usually take the books to be returned back to the counter and settle up whatever late fees we might have accrued. After finishing this task on this particular Saturday I decided to check out the Book Nook, the library’s own used bookstore, composed largely of donations or books the library has decided, for one reason or another, to excise from their inventory. I can usually find some dog-eared volume on Watergate, or perhaps a celebrity biography on which it might be worth taking a 50-cent chance, but usually the shelf rotation is pretty stagnant, so I don’t go in all that often. But this day I felt like poking around. Unfortunately, I was seeing many of the same books I usually see-- an awful lot of John Patterson was hogging the fiction shelves, and all the Watergate and Nixon stuff was the leavings I’d already pawed through several times already. Even the film section was fairly paltry, though it had been moved to the opposite side of the small room space the Book Nook called its own. As I rounded the corner into the third row of shelves where the film books were located I let out an audible “Oh, my God!” which was audible and emphatic enough that the volunteer the Nook’s cash box said, “Is everything all right?”

“Oh, yes,” I think I said—I don’t actually remember if I replied. I was too busy staring at the cart at the end of the row, parked up against the window and thrown into dim silhouette against the sun streaming in from outside. On the bottom rack of the cart was an entire set of Encyclopedia Brittannica, quite the treasure indeed. But this was not what had inspired my bark of joy. On the top shelf of the cart, stretching from end to end, was a row of at least 25, maybe 30 volumes of John Willis’

Screen World. There were a couple of copies from random years in the ‘50s, one or two from the ‘60s, and starting from 1970 the entire run of

Screen World up through 2003 was sitting right in front of me. My defenses spoke first—“Christ, they probably want $10 apiece for these things,” I thought to myself, not remembering that I was in a room where the highest price for an item was usually around a buck and a half. Then I noticed the little yellow bookmark sticking out of the top of each and every book which said, “For sale $3.00 each.” My heart began to race. The shoe is going to drop here at some point. What was it going to be? These volumes, each one, were library copies, so they sported conspicuous Dewey decimal system markings on the spine. But who cared? They also each had nice transparent dust jackets, standard operating equipment for most libraries, and they looked to be in at least “very good” condition.

But no sooner than my heart had set a nice racing acceleration speed, it had to quickly gear down somewhat. I opened one of the early volumes—1953, I believe—and I was horrified to discover that, like the volumes I encountered at that Glendale used bookstore a decade earlier, this book had been butchered, ransacked for stills, and left for dead. There was copious accounting on the inside cover, in the handwriting of some studious, hard-working librarian, as to the exact pages that were either missing or mangled, as well as a note to someone with instructions on backtracking the identity of the last person who checked the book out, presumably now the possessor of a whole bunch of neat black-and-white stills unceremoniously hacked out of the book and, what—Scotch-taped to his or her refrigerator? Shit. Here we go again. I put down 1953 and picked up 1967-- the same dirty deal. No, no, no, no. 1971—destroyed. 1972—mutilated. Then suddenly, with expectations thoroughly trampled, here was 1974, the year of my originating obsession, in my hands again, and this volume was in perfect condition. I began slowly opening and examining each of the remaining volumes, and each one—1969, 1970, and everything from 1973 to 2003—in perfect f-ing condition. I actually had to take a breath to keep from bursting into tears right there in front of the library volunteer, who was still concerned that something might be wrong. She renewed her fear when, after about 15 more minutes of examination and weighing which books I would most want to walk out of there with, I rounded the corner to her desk with nine books stacked in my arms. I figured that my wife wouldn’t mind if, out of those 30 or so books sitting on that cart, I judiciously chose nine of them to take home without first running it past her. (I wear the pants, she keeps the books, you see…) So I laid down my $27 in exact change (which the library volunteer greatly appreciated) and headed upstairs with my bounty. I couldn’t wait to show off my discovery to my wife, in the hopes that in seeing the books after all this time she might feel a degree or two less bad about the decision I had made so many years ago.

If anything, the grin on her face was bigger than mine when I revealed my treasure. I told her that I’d forced myself to choose, that I could have spent another 60 bucks or so to pick up the entire rack, but even at that ridiculously low price $100, for a family budget like ours, adds up to a pretty big notch in the bark. And of course, she didn’t yell at me for spending the $27. Instead, she insisted that we go back downstairs and buy the remaining volumes! Seems the mantle of guilt she’d assumed over my selling the books was still weighing pretty strongly with her, and this chance to drive a stake through its heart was more than she thought either one of us should resist. So we gathered up our daughters' book picks and when story time was finished we headed back down to the first floor to relieve the Book Nook of the rest of the bounty that seemed to be of so little value, suddenly, to anyone but me and my wife.

Well, I’ll be damned if, in the ensuing 20 minutes between when I left and when I came back, that library volunteer hadn’t shut the Book Nook’s doors for the day, leaving a little sign in the window bearing the promise of return “sometime tomorrow.” I wasn’t worried about it—I was still glowing over the initial find—but my wife was knotted up about this near miss and insisted that we come back the next day and clean out the remaining Willises before someone else who shared the same cultural mutation as I came in a snapped them up in a frenzy. The library opened the next day at 12:00 noon, and I’m sure it was probably around 12:04 that she and I burst back into the Book Nook and headed straight for that portable rack at the far end of the third row of bookshelves. The books that I had yesterday left for someone else were still there. I showed my wife the notes on the various mutilations in the unfortunate books, and we pored over each remaining volume, assuring ourselves that each one was complete and truncated not by so much as a page. And after we were satisfied, I gathered 24 more volumes of

Screen World in my arms and the two of us walked out of the library triumphant. How wonderful to be reunited with these books, which are, in the age of IMDb, largely superfluous and cumbersome and clunky and relatively incomplete. And how wonderful that my wife, who had taken so personally my decision to use my original collection to fund one night in a series of wonderful nights that we used to get to know each other and to eventually fall in love, could be part of that reunion. My original collection of John Willis’

Screen World dated from the 1974 volume up through the 1986 edition. I now have

two copies of the 1974 and 1976 editions, and the years covered go from 1969 and 1970 (missing 1971 and 1972) to 1974, up through 1978 (missing 1979), and then from 1980 all the way to 2003, now easily twice and closer to three times what it was at its most complete. I will keep my eye out for those missing editions, but to my mind I need worry or obsess no further—this is the collection I will have to pass on to my daughters when the day comes, surely then only as quaint and near-useless antiquities, tokens of a time when books were the primary sources transmitters of knowledge and minutiae and ineffable wonder. But maybe I’ll get lucky and they’ll see them also as a connection to the movies that made me fall deeply in love with the movies, and maybe they’ll have some real connection of their own to those movies, or the movies in general, that will render the books as special and meaningful to them. If nothing else, they will know the story of my history with them, and the small part the books played in bringing their mother and I together. Perhaps my daughters will treasure them for no other reason than that, and that will be good enough.

Sting certainly got a lot of mileage out of the idea, and made enough money off of it, but I think it was one of the happening young nuns (think Helen Reddy in

Airport 1975) in my catechism classes back in the ‘70s who originated the notion (at least to me) that if you love somebody you must let them go their own way, and if the love be true then you would one day again be united. Well, I know of a lot of young ladies in my past that I let go (my editor insists that I be truthful and admit that I was

always the one being “let go”), and I guess it wasn’t really love because I’ve seen hide nor hair of any of them since. But how nice to think that some wrinkle in that tidy little Catholic bromide seems to have worked itself out in my real world, after 20 years no less. I loved those books, but I loved a woman more and was able to grin and bear it long enough to take those books and trade them for the hope of a future with her. Fifteen years of marriage, a tragic loss (and the ensuing haunted life), and then two lovely young testaments to our love later, and my wife is there with me to help restock my book shelves. She took a gander through one of the volumes last week and had to admit that she didn’t quite get the fuss over what was inside them, and that’s okay. This may very well be a case of “you just had to be there” watching for the specific way that the books shaped my feelings and hunger for the movies to have any real understanding of why I was so excited when I entered that library bookstore a couple of weeks ago. But she does understand that they hold a lot of meaning for me, and for us, and I think it was that, rather than guilt, which drove her to insist on returning to grab the entire set. For this understanding I will always love her far more than I have ever or will ever love John Willis’

Screen World, and now the first thing I will think of when I see one of the books on my bookshelf, rather than who directed

The Train Robbers or the true age of Polly Bergen, is how much she loves me, and how much I love her.

****************************************************