THE SLIFR 2011 MOVIE MIDTERM REPORT...... THE JOURNEY SO FAR

Here we are, on the eve of the eighth month of 2011, well over the halfway point and past the moment where most of us who have a tendency to want to do these sorts of things start the process of looking back and making grand proclamations about the year in movies-- or books, or videogames, or technology, or whatever-- so far. It’s not like there’s much that can be said conclusively about a year that still has five months-plus left in the tank, and in my case, as it happens every year, much of those remaining five months will be spent trying to dole out time to see new releases that will be hugging screens in anticipation of year-end awards, as well as seeking out and hooking up with the stuff I couldn’t manage to see from January through July that will soon be debuting in the more user-friendly (read convenient or lazy, whichever suits your mood) format of home theater.

Speaking of which, any assessment of the year for me has to include my increased exploitation of streaming media and my relatively life-changing introduction, a good 10 or so years after everyone else figured it out, to the DVR. I’m still relatively new to digital video recording—there’s barely any dust collected on the spiffy receiver box supplied to me a couple of weeks ago by DirecTV, and in the cluttered no-Windex zone that is my humble abode that’s really saying something. And I have managed to actually watch a couple of the 10-12 movies I’ve recorded—Jean Negulesco’s Three Strangers (1946) is an interesting melodramatic curio starring that Casablanca/Maltese Falcon tag team of Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, spurred on by the delicious Geraldine Fitzgerald (whose psychosis is revealed gradually, tantalizingly) as the titular unfamiliars whose lives take some fatal left turns after making a wish over the statue of a Chinese goddess; and Michael Curtiz’s odd, engaging British Agent (1936), featuring Leslie Howard and Kay Francis in a juicy tale of political intrigue set against the nascent Russian revolution of 1917. (In the ever-growing queue: Bill Forsyth’s Housekeeping, Tom Holland’s-- and Don Mancini’s-- Child’s Play, Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort, all in HD, plus several others.) And ever since I added Vudu to the menu of choices available through the magic of my Playstation3 hub, I have become much closer to the stay-at-home viewer most coveted by corporate drones and purveyors of the shrinking of the cinematic experience. Needless to say, the recently announced and publicly trounced Netflix rate hike has assured that the at-home model for acquisition of movies will continue to change, at least for those of us unwilling to acquiesce to the mail order gargantuan’s overreaching greed. I’m also inclined to resist the shrinking of the movie image—I’m all for the convenience of a DVD player on my laptop, but seeing movies on a 4G Smartphone, however, still holds no appeal for me.

Speaking of which, any assessment of the year for me has to include my increased exploitation of streaming media and my relatively life-changing introduction, a good 10 or so years after everyone else figured it out, to the DVR. I’m still relatively new to digital video recording—there’s barely any dust collected on the spiffy receiver box supplied to me a couple of weeks ago by DirecTV, and in the cluttered no-Windex zone that is my humble abode that’s really saying something. And I have managed to actually watch a couple of the 10-12 movies I’ve recorded—Jean Negulesco’s Three Strangers (1946) is an interesting melodramatic curio starring that Casablanca/Maltese Falcon tag team of Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, spurred on by the delicious Geraldine Fitzgerald (whose psychosis is revealed gradually, tantalizingly) as the titular unfamiliars whose lives take some fatal left turns after making a wish over the statue of a Chinese goddess; and Michael Curtiz’s odd, engaging British Agent (1936), featuring Leslie Howard and Kay Francis in a juicy tale of political intrigue set against the nascent Russian revolution of 1917. (In the ever-growing queue: Bill Forsyth’s Housekeeping, Tom Holland’s-- and Don Mancini’s-- Child’s Play, Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort, all in HD, plus several others.) And ever since I added Vudu to the menu of choices available through the magic of my Playstation3 hub, I have become much closer to the stay-at-home viewer most coveted by corporate drones and purveyors of the shrinking of the cinematic experience. Needless to say, the recently announced and publicly trounced Netflix rate hike has assured that the at-home model for acquisition of movies will continue to change, at least for those of us unwilling to acquiesce to the mail order gargantuan’s overreaching greed. I’m also inclined to resist the shrinking of the movie image—I’m all for the convenience of a DVD player on my laptop, but seeing movies on a 4G Smartphone, however, still holds no appeal for me.

There is, however, a bigger benefit for me to the whole stream-at-home option, beyond the primary advantage of cutting loose from the drudgery of the Blockbuster experience, or even from the sad queue at my local supermarket in front of those giant red DVD-spewing robots that charge you a buck for a movie, then count on your Netflix-nurtured laissez-faire attitude toward actually watching the movie while an extra buck piles up on your credit card every night you blow off actually watching the film. That advantage is, simply, being able to endlessly scroll through Vudu’s list of brand-new, HD-quality features, as well as their hefty back catalog, or lazily punching up yet another tasty oddity for my personal Netflix queue that seems available only through this service. This brilliant new wrinkle on channel surfing creates a powerful virtual illusion: it duplicates the often exciting experience of thumbing through one’s own vast DVD/Blu-ray library without the disadvantage of actually having bookcases of space-hogging DVDs to actually thumb through or (and this is really important) having to buy the damn thing first. For me, the availability of the Vudu/Netflix channel surfing option has dramatically altered my DVD-buying habits and reduced that familiar desire, like a gnawing hunger in the pit of a cinephile’s belly, to snap up every title that looks tantalizing or otherwise casts some sort of spell that dissipates by a significant degree the minute the shrink wrap has been torn away.

I actually walked into a Barnes and Noble a couple of nights ago completely unaware that their apparently bi-annual 50% sale on Criterion DVD and Blu-rays was under way. I thumbed my way through their selections and noted the ones which I still coveted, but at no time was I seized by a serious desire to pick up four or five of them and start justifying the expense in my head as I headed toward the cashier. I credit this sanding away of my typically sharp impulse to smash-and-grab in this precise situation to the fact that I knew that many of these same titles were available on one or the other of the services I had available to me, and most often in high definition, thereby eliminating the sinister undertow otherwise known as pride of ownership. (It also helped to remember that I still have a stack of actual, physical, as-yet-unwatched DVDs and Blu-rays at home, Criterion or otherwise, that, should I start watching one a night, would last me at least two years.) It seems that in order to get me to seriously consider a DVD or Blu-ray purchase these days the title must be sufficiently niche, perhaps a title previously hard to find, or have a ridiculously low price tag (for Blu-ray, I don’t even raise an eyebrow for anything over $9.99 these days).

Streaming has also increasingly become a viable way of catching up with new releases, as companies like Magnolia, Magnet and others make available acclaimed genre titles like 13 Assassins, Hobo With a Shotgun and Trollhunter that could very well end up in the year-end best-of discussion, at least on some of the more interesting lists. One that I saw in this format, Christopher Smith’s Black Death, will certainly figure in the one I’ll be undertaking here in a few months. This grim historical drama-horror film, whose roots are secured deep in the same ground as that in which inquisitor classics like The Witchfinder General (1968) are planted, plays uncertain fear of the exact nature of the Black Plague—the time is 1348—against an even greater fear of those who would operate outside the bounds of accepted Christian faith and fealty. Sean Bean (Britain’s apparent go-to representative on ambivalent medieval manhood) leads a group of righteous warriors in search of a village rumored to be the only one unaffected by the shroud of death enveloping the countryside, one rumored to be led by genuine necromancers.

It becomes clear early on that the villagers operate on their own moral order, under the guidance of village leaders Tim McInnerny and Carice Van Houten and, perhaps, a supernatural influence as well. They recognize the warriors, who claim to be only wandering knights, for what they are--- neither band is long fooled by the other-- and the gruesome delight of Black Death lies partially in discovering just how demented both sides are. The movie is a spectacular display of medieval torture, including the flaying of religious philosophy, and the rich bloodline of horror movie iconography; grim and unrelenting, Smith is a genre director who knows on which side of the blade his heavy scimitar has been caked with mud and blood. Here theistic debate and the historical formalities of the horror genre coexist with gusto; within the construct of this twisted epic, the filmmaker’s nihilism is well earned and well accepted.

It becomes clear early on that the villagers operate on their own moral order, under the guidance of village leaders Tim McInnerny and Carice Van Houten and, perhaps, a supernatural influence as well. They recognize the warriors, who claim to be only wandering knights, for what they are--- neither band is long fooled by the other-- and the gruesome delight of Black Death lies partially in discovering just how demented both sides are. The movie is a spectacular display of medieval torture, including the flaying of religious philosophy, and the rich bloodline of horror movie iconography; grim and unrelenting, Smith is a genre director who knows on which side of the blade his heavy scimitar has been caked with mud and blood. Here theistic debate and the historical formalities of the horror genre coexist with gusto; within the construct of this twisted epic, the filmmaker’s nihilism is well earned and well accepted.

Regardless of format, I was lucky enough to see Black Death early on in the year, concurrent with its meager theatrical release, early enough to give me hope that the coming year would be, in the end, as good as the last one ended up being. And I saw the best movie of 2011 (so far) way back in October 2010—Kelly Reichardt’s beautiful, otherworldly Meek’s Cutoff seems not only distanced by how much time has passed since it passed over my eyes and through my head; it seem distanced by its very existence. Reichardt frames her film as if we were looking through a stereopticon at opaque images piped directly from the past. (The movie is shot in the perfectly square 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which underscores its direct relationship to our perceived past, as if it were a tattered photograph glimpsed in a display case of classic Hollywood arcana.) The movie’s images may be opaque, but they are pointedly not sepia-toned—Reichardt’s images, shot by talented cinematographer Chris Blauvelt, are immediate and harshly lovely, attendant to the tactility of the desert, in long-shot long takes as well as lingering close-ups, and sensitive to the tension of the unrelenting sun, as well as that of the creeping nightfall that surrounds these travelers who know not where they’re really going. Meek’s Cutoff tells the story of a group of Oregon Trail pioneers who, at the film’s beginning, are already aimlessly plodding across the parched plains of the West under the guidance of a scout (Bruce Greenwood) with a sketchy past who may be leading them, by design or by incompetence, to their slow-baked doom. The three couples (and the children) under Meek’s watch include Solomon Tetherow (Will Patton), who hired Meek for a job which the others come to suspect he may not be qualified, and Tetherow’s wife Emily (Michelle Williams). Emily’s distrust of Meek leads her to openly question, and then stand up against not only his judgment but his dismissal (and abuse) of an Indian whom they capture and who eventually begins to usurp Meek’s authority over the barren ruthlessness of the landscape. (One of the less-ruthless landscapes of the movie is Williams’ face, yielding yet tough, open yet firm, unassuming yet subtly aggressive. It’s a performance to equal Williams’ best work, which includes her Oscar-nominated turns in Blue Valentine and Brokeback Mountain as well as in Reichardt’s previous film Wendy and Lucy.)

Meek’s Cutoff looks and feels like no other on the movie landscape this year; it presses on, at the pace of its characters, quietly assuming its position at the head of a pack of far more ostentatious claims to our attention, including movies as disparate as Transformers: Dark of the Moon and Terence Malick’s Tree of Life. They all have vocal supporters and detractors and have already positioned themselves upon the docket for discussion of the year’s most important movies, for wholly different reasons, of course. But Reichardt’s movie (shot in collaboration with screenwriter Jon Raymond) has a unique authority amongst this year’s treasures; it knows the value of what can be communicated by a glance, a gesture, by silence, by absorption into the frame through means more contemplative than cacophonous. It is the movie that disproves the notion that the squeaky wheel gets the grease, unless of course that squeaky wheel is one which roughly rolls a covered wagon over the parched crevices of a withered and parched lake bed, each squeak rhythmically underlining the existential dilemma of the film’s characters like agonized sonic poetry carried along the most arid of desert winds.

The rest of the year has not been so transcendent, which is not to say that it has been without its treasures. But certainly in the realm of what is now referred to as “family entertainment” the pickings have been somewhat slimmer than what we’ve become used to in this supposed renaissance era of animation. By this time last year we already had films of indisputable quality like Despicable Me, How to Train Your Dragon, The Secret of Kells and Toy Story 3 under our belts, with The Illusionist and Tangled still to come. That’s a formidable lineup, and so far only one animated film that I’ve seen this year belongs in that stellar company—Gore Verbinski’s Rango, which is so smart, so strange, so well-acted (I’m sure Johnny Depp will make my top-five list of best performances this year, and Isla Fisher might too) and so tactile that I’ve almost come to think of it not as artificially imagined but instead as a wide-screen transmission from a vaguely recognizable but separate world where lizards and cats and dogs are living with each other and acting out a peyote-buzzed alternate version of human (movie) history. To my mind and eye, even the next-best offerings for the family demographic—the exquisitely realized Kung Fu Panda 2 and the down-and-dirty Diary of a Wimpy Kid 2: Rodrick Rules-- come up woefully short of Rango in every conceivable category.

Other pictures, like Rio and Hop, are mainly distinguishable by being considerably less bad and obnoxious than I expected them to be, and as a dutiful dad accompanying my kids to the drive-in, where we saw every one of the pictures in this category (I’ve since seen Rango twice more indoors), at least I did not fall asleep during either Hop or Rio, which is more than I can say about Cars 2. Pixar’s incredible run was blemished slightly by the first Cars (2006), which was still a terrific movie by most any other animation studios standards. But measured against what Pixar had done up to that point, it seemed a bit of a letdown, conceptually middle of the road, if a driving metaphor must be invoked, and much closer to an advertisement for a future line of toys than any of its far-more-soulful predecessors. But that 2006 model seems downright organic compared to the higher-octane sequel, which to these weary eyes and ears had an air of desperation about it from the very beginning. All the winks and jabs and asides to James Bond and other spy adventures seem welded on to the original’s folksy chassis with little care, and after the requisite pulse-pounding, slam-bang opening, the movie’s first-gear retreat to Radiator Springs to get the machinations of the plot in motion sent me into sweet slumber, like a cranky baby at the beginning of a long road trip. The only other thing I know about Cars 2 is that there seems to be another Rascal Flatts song involved, this one over the end credits, the only other part of the movie for which I remained awake.

Other pictures, like Rio and Hop, are mainly distinguishable by being considerably less bad and obnoxious than I expected them to be, and as a dutiful dad accompanying my kids to the drive-in, where we saw every one of the pictures in this category (I’ve since seen Rango twice more indoors), at least I did not fall asleep during either Hop or Rio, which is more than I can say about Cars 2. Pixar’s incredible run was blemished slightly by the first Cars (2006), which was still a terrific movie by most any other animation studios standards. But measured against what Pixar had done up to that point, it seemed a bit of a letdown, conceptually middle of the road, if a driving metaphor must be invoked, and much closer to an advertisement for a future line of toys than any of its far-more-soulful predecessors. But that 2006 model seems downright organic compared to the higher-octane sequel, which to these weary eyes and ears had an air of desperation about it from the very beginning. All the winks and jabs and asides to James Bond and other spy adventures seem welded on to the original’s folksy chassis with little care, and after the requisite pulse-pounding, slam-bang opening, the movie’s first-gear retreat to Radiator Springs to get the machinations of the plot in motion sent me into sweet slumber, like a cranky baby at the beginning of a long road trip. The only other thing I know about Cars 2 is that there seems to be another Rascal Flatts song involved, this one over the end credits, the only other part of the movie for which I remained awake.

In the realm of the standard-issue action movie, sheer volume usually ensures that there will be no sleeping, and that premise certainly held true for Fast Five. This is the fifth and most preposterous of the ludicrously popular and now-apparently numerically infinite FastFurious franchise, most of the fun of which has devolved into guessing what absurd configuration will represent the title of the next installment of the series. (I’m backing FastSixFurious, but gas prices being what they are the more economical FF6 seems the more eco-responsible choice, not to mention being much more text-friendly.) The level of asininity reaches choke-inducing levels in Fast Five, as does the all the macho posturing that takes the place of acting, attitude which by the way is not held in check by mere gender—the women are just as arrogantly stupid, and ultimately action-movie sentimental as the men. That said nothing beats the sight of a bald, oiled-up and hyperinflated Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson puffing chests and trading intimidating glares with the slightly softer, slightly less articulate Vin Diesel. When these two bulletheads finally go at it mano a mano, the concept of a human cockfight is defined and redefined before your very eyes.

Liam Neeson doesn’t fare much better in Unknown, which at least has sleek Euro locales and a coldly metallic blue sheen where Fast Five had only the nitro-injected lust to best Michael Bay at every rubber-laying turn. The problem is that Unknown also has a logically perforated premise—a doctor awakens from a coma to find that everyone he once knew denies that he is who he says he is-- that depends on sleight of hand in order that we may more easily disregard the story’s myriad absurdities, and director Jaume Collett Serra (Orphan) isn’t enough of a magician to pull off the task. The shaggy, cruddy exploitation vibe of Drive Angry is what Unknown, with its classy drapery of Hitchcockian nods, is trying to disavow, but it would have been better off embracing its B-movie lineage. Nicolas Cage, like Neeson, rides alone, and he too picks up a sleek travel partner, but Drive Angry’s shotgun-riding Amber Heard could mop the barroom floor with Neeson’s spunky taxi driver, played by Diane Kruger. Cage is an escapee from Satan’s nightclub, a.k.a. Hell—he’s come back to Earth searching for the dimwitted occultists who killed his daughter and kidnapped his baby granddaughter, and he’s got a deadpan agent of the devil (William Fichtner) on his tail. Drive Angry is merely an excuse for lots of Race with the Devil-style auto action, all souped up with detached wheels and chunks of flaming metal comin’ at ya in 3-D, and if it’s not a patch on last year’s triumphantly trashy Piranha 3-D, well, it all still goes down like a cool summer night in 1977 at the drive-in. Somewhere in his art-exploitation Cineplex in the sky, Paul Bartel is nodding with approval.

One of the year’s best turns of adult-oriented drama so far came from Joe Wright’s beautifully disorienting Hanna, its soul electronically wired to its thrumming, sonically fertile soundtrack (designed by the Chemical Brothers) and patched through a fairy tale sensibility that even Grimm might at times find too grim. Saoirse Rohan is a 16-year-old trained by her father, Eric Bana, in the ways of survival, martial arts, the ascetic life of a perfectly focused assassin, and then sent on a mission to confront the agent (Cate Blanchett) who knows all about her past. It’s an enthralling piece of work, certainly as a formal exercise in the ways that familiar premises can be invigorated by a fresh stylistic approach, but primarily as a showcase for the feral beauty of the choices made by Rohan, an intuitively inquisitive actress who doesn’t seem to be processing her material as much as interpreting it from the inside out. Conversely, Matthew McConaughey has seemed, from his revelatory turn as the benignly predatory Wooderson in Dazed and Confused straight on through to his unofficial reign as King of the Rom-Coms, all sleek and buffed surface charm. But that characteristic veneer of charm and swagger is part of the subject of The Lincoln Lawyer,

or at least how that swagger is undermined for McConaughey’s character, a successful defense lawyer named Mick Haller operating on the outskirts of legal procedure in Los Angeles (he works out of the Lincoln Towncar of the film’s title). The actor, whose level of confidence has always been mixed up with a slightly slurred aura he apparently can’t help but exude, at first seems an odd choice for a brash and amoral defense attorney. But the movie, directed by Brad Furman, is as stylish and comfortable as that vehicle, and McConaughey sinks into it as if it was a back seat made of rich Corinthian leather. His good-ol’-boy arrogance is a perfect foundation for the moral crisis in which he finds himself embroiled when he takes on the case of a rich Bel Air trust fund baby accused of a brutal attack on a prostitute. The defendant is played by Ryan Phillippe, another actor whose petulant, entitled good looks are well used here; the entire movie is well cast, with worthy roles for everyone from William Macy and Marisa Tomei to Josh Lucas, Michael Pena, and even Laurence Mason in the not-quite-stock role of McConaughey’s driver. The movie flirts with a bit too much attention-diverting camerawork at times, but it’s a solidly conceived, completely satisfying thriller, the kind that used to be a John Grisham-inspired Hollywood cottage industry 15 years ago, the difference being that, with the exception of Joel Schumacher’s The Client none of them were much good. Nowadays movies like The Lincoln Lawyer, if they get made, have no such world-conquering expectations laid on them. A friend of mine recently speculated that the modest returns on this picture were enough to make it a hit, but that it’s basically considered arthouse fare, “too small to be a proper studio movie.” Hopefully the adults who make up the demographic most likely to be interested in a well-made movie like this one won’t have their will to march out to the movies beaten out of them by the next round of Hollywood blockbusters by the next time the next Mick Haller picture arrives.

or at least how that swagger is undermined for McConaughey’s character, a successful defense lawyer named Mick Haller operating on the outskirts of legal procedure in Los Angeles (he works out of the Lincoln Towncar of the film’s title). The actor, whose level of confidence has always been mixed up with a slightly slurred aura he apparently can’t help but exude, at first seems an odd choice for a brash and amoral defense attorney. But the movie, directed by Brad Furman, is as stylish and comfortable as that vehicle, and McConaughey sinks into it as if it was a back seat made of rich Corinthian leather. His good-ol’-boy arrogance is a perfect foundation for the moral crisis in which he finds himself embroiled when he takes on the case of a rich Bel Air trust fund baby accused of a brutal attack on a prostitute. The defendant is played by Ryan Phillippe, another actor whose petulant, entitled good looks are well used here; the entire movie is well cast, with worthy roles for everyone from William Macy and Marisa Tomei to Josh Lucas, Michael Pena, and even Laurence Mason in the not-quite-stock role of McConaughey’s driver. The movie flirts with a bit too much attention-diverting camerawork at times, but it’s a solidly conceived, completely satisfying thriller, the kind that used to be a John Grisham-inspired Hollywood cottage industry 15 years ago, the difference being that, with the exception of Joel Schumacher’s The Client none of them were much good. Nowadays movies like The Lincoln Lawyer, if they get made, have no such world-conquering expectations laid on them. A friend of mine recently speculated that the modest returns on this picture were enough to make it a hit, but that it’s basically considered arthouse fare, “too small to be a proper studio movie.” Hopefully the adults who make up the demographic most likely to be interested in a well-made movie like this one won’t have their will to march out to the movies beaten out of them by the next round of Hollywood blockbusters by the next time the next Mick Haller picture arrives.

Of all the familiar types of movie genres I’ve indulged in this year, perhaps it’s the comedies that have delivered the most, in terms of wear, tear and soreness on the diaphragm muscles, for my precious and few entertainment dollars. Simon Pegg and Nick Frost’s fanboy paean Paul was a delight, even affording the nitpicking. Why, for example, would such obvious candidates for believing have such an initially hard time accepting the discovery of an alien life-form, their greatest fantasy come true? And enough with the fervent worship at the altar of the Cult of George Lucas, please. The movie’s insistent referencing of the usual sacred source material makes for the laying of an occasional rotten egg—the Star Wars cantina theme is playing when our boys drop into a local diner. Funny, right??!! Fortunately, Pegg and Frost are brilliant, as usual, together, and they get stellar (get it?) support from Seth Rogan as the voice of the titular spaceman and Kristen Wiig as a one-eyed preacher’s daughter who hooks up with the trio and gets her faith shaken, then stirred by the existence of Paul.

Of all the familiar types of movie genres I’ve indulged in this year, perhaps it’s the comedies that have delivered the most, in terms of wear, tear and soreness on the diaphragm muscles, for my precious and few entertainment dollars. Simon Pegg and Nick Frost’s fanboy paean Paul was a delight, even affording the nitpicking. Why, for example, would such obvious candidates for believing have such an initially hard time accepting the discovery of an alien life-form, their greatest fantasy come true? And enough with the fervent worship at the altar of the Cult of George Lucas, please. The movie’s insistent referencing of the usual sacred source material makes for the laying of an occasional rotten egg—the Star Wars cantina theme is playing when our boys drop into a local diner. Funny, right??!! Fortunately, Pegg and Frost are brilliant, as usual, together, and they get stellar (get it?) support from Seth Rogan as the voice of the titular spaceman and Kristen Wiig as a one-eyed preacher’s daughter who hooks up with the trio and gets her faith shaken, then stirred by the existence of Paul.

Rogen also co-wrote and starred in The Green Hornet, which I think is a lot funnier and more entertaining than its hideous reputation would ever allow. It’s a lark, and undoubtedly an expensive one, but it has an infectious spirit and a terrific cameo by a recent Oscar show host that’s among his zippiest minutes on screen. And Wiig, of course, made a mark for herself and for comedies focusing on women (you remember those, the ones studio executives have claimed for years no one wants to see) when Bridesmaids took over the early summer box office tallies. Wiig is heartbreakingly funny as a woman who finds her number-one status being usurped during the planning of her BFF’s wedding. But Bridesmaids surprised me not only in its level of Apatow-style gross-out humor (which is very funny), but also in its depth of feeling, and its access of that feeling sans mawkishness. Wiig is also surrounded by comic performers who turn out to be every bit her match, including Maya Rudolph (the BFF), Melissa McCarthy, Wendi McLendon-Covey (please, someone get this woman her own movie) and Rose Byrne. For those who may have forgotten her hilarious turn in Get Him to the Greek, the revelation of Byrne as a swift and subtle comic performer may turn out to be the year’s happiest movie surprise.

Also surprising was the level of dismissal afforded Bad Teacher, a mildly transgressive comedy in the Bad Santa mold which provides a showcase for the comic fizz of another female star, Cameron Diaz (who has much more going on here than in her perfunctory role in The Green Hornet.) Diaz plays a narcissistic junior high school teacher who dumps her job and then gets in turn dumped by her rich boyfriend. She’s forced back to work in order to finance her dream of the ultimate boob job, which she figures will be her ticket to fame and fortune, if not simply leaving her checkered past in the education system far behind her. The movie is slickly, cynically hilarious, but general audiences (even the one I saw it with) did not get behind its rude worldview. My theory is that audiences will make room for a drunken, besotted Santa Claus, but a coke-snorting gold-digger at the center of a movie that suggests our educational system is insular, out of touch and populated with conservative snobs and dolts who haven’t a clue how to reach out and actually engage students—well, what’s funny about that?

The laff machine I’ve liked most so far in 2011 is one that’s gotten the worst reviews, probably even worse than Bad Teacher. (Remember, I loved Land of the Lost and Year One.) You would think that, for audiences of a certain age and a certain bent, Your Highness, with its gleeful perforation of the kinds of indulgent medieval epics that were de rigueur in the ‘80s, interspersed with anachronistic foul language and drug use, to say nothing of a minotaur with a mythologically imposing hard-on, would be an instant classic. And in places where midnight movies still mean what they did when I was in college (do these places still exist?) it may one day achieve that status. Danny McBride and James Franco are hilarious together as mismatched sons of an arrogant but benign king who set out on a quest to retrieve Zooey Deschanel, Franco’s moony would-be bride, from the clutches of a spectacularly lecherous wizard, played by Justin Thereoux. Along the way they stumble upon Natalie Portman, she of the awesome bod and the recent Oscar, who is brilliantly, pointedly awful as a vengeful warrior (mm-hmm) with her own agenda. (“I must surprise a band of thieves and burn them alive in a symphony of shrieks,” she flatly intones at one point, causing me to go temporarily mad with glee.) The movie is crude and obnoxious, of course, and it doesn’t have the subversive wit of its obvious model, Monty Python and the Holy Grail. But when it is on, Your Highness delivers that special high piped straight from comedy heaven in larger doses than any other picture I’ve seen this year.

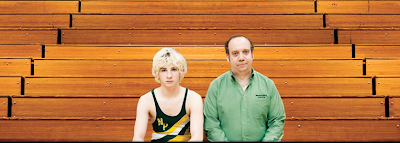

More adult-oriented comedies have fared pretty well too. The best comedy I’ve seen so far this year is Win Win, the latest wry missive from the heart of writer-director Tom McCarthy, who last directed The Visitor and whose wonderful film The Station Agent provided an excellent first-film blueprint for emotionally acute comedy which McCarthy seems to be fulfilling right on schedule. McCarthy’s lead is the impeccable Paul Giamatti, who seems to be carving out quite a career for himself as the poster boy for curdled hopes and dreams. Here Giamatti plays a small-town lawyer whose economically depressed business leads him to assign himself as conservator of the estate of an Alzheimer’s-afflicted client (Burt Young) so he can “borrow” the money to keep his practice alive. Giamatti also moonlights as a high school wrestling coach, and when Young’s grandson, abandoned by his drug-addict mother, comes to visit and is revealed to be a talented wrestler himself, Giamatti takes him under his wing without disclosing to the boy, or to his wife (Amy Ryan, a force of nature), how he’s been manipulating the old man’s money. The director closest to McCarthy’s sensibility is, at this point, Bill Forsyth, who knew how to weave “quirky” into the fabric of his stories without ever betraying the audience’s trust, and Win Win is a master class of rich character touches that are similarly turn-your-head funny and believably, achingly human. McCarthy’s touch is unforced and realistic, leavened with a slight dusting of whimsy, and his cast, including the aforementioned along with Jeffrey Tambor, Margo Martindale, Bobby Cannavale and Melanie Lynskey, are confident without a hint of smugness, as if they intuitively knew what good, kind hands they were in. The boy, played by Alex Shaffer, has raw presence too. He may not be turn out to be an actor in a class with his other cast mates, but his performance here has real power, anger and the sting of betrayed innocence. A side note: Win Win, like The Station Agent and some of the wistful films in Forsyth’s filmography, has the wisdom to know just how and when to end, and that ending, like those of the other films, comes on an unexpected beat. It feels like grace.

The elliptical and emotional Beginners sings roundelays around the great subject of sadness and loss in telling the story of a commercial artist (Ewan McGregor) who finds out in fairly quick succession, upon the death of his mother, that his father (a marvelous and sly Christopher Plummer) is gay and soon after that that the man is dying of cancer. McGregor also strikes up a relationship with an actress (Melanie Laurent) whose presence in his life seems as fleeting as everything else he holds dear. But the movie is practically miraculous in the way it avoids the melodramatic pitfalls usually associated with the accounting of parental reckoning and passing we usually see in American movies. (This ain’t no Tribute or Tuesdays with Morrie.) Credit for that has to go to writer-director Mike Mills, drawing on his experience with little see-me-feel-me pleading and plenty of agility in making connections between thoughts, glances and entire scenes that bump into each other throughout this movie in unexpected ways.

And unexpected is certainly one of the primary words I would use in describing Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. It’s easily the director’s best movie since Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), and audiences have made it (adjusting for inflation and all that, of course) his biggest hit ever, at $46 million and counting surpassing even Annie Hall, Manhattan and Hannah and Her Sisters. What was most joyous to me about Midnight in Paris, apart from the initial conceit of the movie, is the way Allen’s usually detached style, full of long takes and frames full of people entering and leaving at random, seems invigorated. He’s using the camera here with passion, alternating close-ups and sweeping postcard imagery of the city with movement and depth of field that suggest he’s engaged by the material for the first time in a long while. Whatever Works felt like a movie made by a man who was throwing his hands up in defeat, but Midnight in Paris feels, for all its flaws (and it is an imperfect gem) like a movie Allen had to make, a consideration of how we ruminate upon and process the past. For Allen in particular this is a fertile subject, given that so much of his oeuvre has been devoted—at least in part—to bemoaning or belittling the current fascinations of pop culture in favor of the achievements of his pantheon of musical, philosophical, cinematic and literary heroes, all of which have been previously sealed and preserved in Allen’s nostalgic amber. Here the amber melts, allowing the director to consider the past as if it were present, with melancholy results. Some have found the very substance of Allen’s fantasia to be a bit too spot on, as if one could actually roam the streets of Paris in the ‘20s and bump into F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel, all of whom would be talking about famous incidents of their creative and personal lives for all the tourists to hear, and all in one night. I had no trouble buying into that fantasy and its attendant jokes because though the concept is pure fantasy it reaches beyond simply trotting out a gallery of literary and society luminaries to something more real, an understanding of the longing behind nostalgia and what nostalgia we can’t understand might mean to someone else.

My problem with Midnight in Paris, such as it is, is that for all the rich imagination poured into his Paris of the ‘20s, Allen still relies on typically lazy caricatures when it comes to the modern world. Owen Wilson, this year’s Allen stand-in, is a hack Hollywood screenwriter with bigger things on his mind, and he’s surrounded by enough shrieking, ugly-spirited Los Angelenos to make anyone want to retreat, either to a glowing, romanticized past or to the nearest dank saloon. His fiancée, Rachel McAdams, is a towering bitch, the entitled daughter of a pair of rich, materialistic Republican retirees who look with disdain upon any professional calling for Wilson that doesn’t guarantee the most abundant lifestyle for their daughter. McAdams is impatient with her soon-to-be hubby, choosing to tour Paris with a boring intellectual know-it-all (Michael Sheen) and his wife while Wilson sleeps all day, after having taken a time-altering coach ride 70 years in reverse and dancing the Charleston with his new famous friends all the previous night. Allen misses the opportunity to enrich the drama of Wilson’s dilemma by giving us not even a sliver of indication as to why Wilson would hesitate for a second to dump the petulant McAdams for the love of his past life, Marion Cotillard. (Cotillard, as it turns out, is a muse who has designs of her own on a time even further past.) And the writer-director makes it too easy on Wilson, and on us, when it is revealed that McAdams has slept with Sheen, thereby excusing any guilt Wilson should probably be harboring over his own not-quite-extramarital designs on Cotillard. Ultimately, Midnight in Paris makes clear that Allen’s imagination is the furthest thing from empathetic—he long ago stopped writing characters, settling instead not even for archetypes but just simple types, easily defined in a few broad strokes, and those who differ from him politically and culturally usually don’t come off too well. These are road bumps, to be sure, and they don’t scuttle the many pleasures Midnight in Paris has to offer. But they are familiar creative flaws to those who have followed Allen’s long career closely, and I think maybe the fact that they smudge even a jewel as radiant as this one might speak to the fact that they are, at this late date, as inseparable from Allen as his wit or his Bergman fixation.

My problem with Midnight in Paris, such as it is, is that for all the rich imagination poured into his Paris of the ‘20s, Allen still relies on typically lazy caricatures when it comes to the modern world. Owen Wilson, this year’s Allen stand-in, is a hack Hollywood screenwriter with bigger things on his mind, and he’s surrounded by enough shrieking, ugly-spirited Los Angelenos to make anyone want to retreat, either to a glowing, romanticized past or to the nearest dank saloon. His fiancée, Rachel McAdams, is a towering bitch, the entitled daughter of a pair of rich, materialistic Republican retirees who look with disdain upon any professional calling for Wilson that doesn’t guarantee the most abundant lifestyle for their daughter. McAdams is impatient with her soon-to-be hubby, choosing to tour Paris with a boring intellectual know-it-all (Michael Sheen) and his wife while Wilson sleeps all day, after having taken a time-altering coach ride 70 years in reverse and dancing the Charleston with his new famous friends all the previous night. Allen misses the opportunity to enrich the drama of Wilson’s dilemma by giving us not even a sliver of indication as to why Wilson would hesitate for a second to dump the petulant McAdams for the love of his past life, Marion Cotillard. (Cotillard, as it turns out, is a muse who has designs of her own on a time even further past.) And the writer-director makes it too easy on Wilson, and on us, when it is revealed that McAdams has slept with Sheen, thereby excusing any guilt Wilson should probably be harboring over his own not-quite-extramarital designs on Cotillard. Ultimately, Midnight in Paris makes clear that Allen’s imagination is the furthest thing from empathetic—he long ago stopped writing characters, settling instead not even for archetypes but just simple types, easily defined in a few broad strokes, and those who differ from him politically and culturally usually don’t come off too well. These are road bumps, to be sure, and they don’t scuttle the many pleasures Midnight in Paris has to offer. But they are familiar creative flaws to those who have followed Allen’s long career closely, and I think maybe the fact that they smudge even a jewel as radiant as this one might speak to the fact that they are, at this late date, as inseparable from Allen as his wit or his Bergman fixation.

Or perhaps as inseparable as Hollywood is from the budget-busting blockbuster effects movie, many of which have broken out of the summer corral and made their omnipresence felt during the other three seasons as well. I somehow escaped taking in Zach Synder’s latest Sucker Punch, and though I think Ryan Reynolds is perfectly keen, I have so far managed to avoid the sickly emerald radioactivity of The Green Lantern. This very weekend the ostensibly sure-fire generics of Cowboys and Aliens seems to be opening to derision from fanboys and critics, which is not to say that it won’t have one of those “Quick, let’s brag about it while we can!” opening weekends that Hollywood executives are so keen on before the inevitable 70% drop-off the following week as the conventional wisdom begins to solidify. But hey, now, I hark from a fanboy-oriented past, and though I have largely thrown off the Big Red Cape of Self-Seriousness that often characterizes the Comic Con-conversant modern breed of this rich cultural stereotype, I am still mightily willing to indulge in a good superhero yarn or other chapter in a fantastical Hollywood blockbuster franchise well told. Thor, for example, sports a hallucinatory design and good humor that seems quite an improvement upon Jon Favreau’s blandly overstuffed Iron Man 2 from last year; and no one was more floored than I was that I would find Transformers: Dark of the Moon tolerable in the least.

I think David Edelstein is absolutely right—this is visionary filmmaking. But eventually it did weigh on me, as it didn’t on him, that the vision was one of giant corporate-endorsed toys smashing everything in sight—Andrew O’Hehir called it a magnificent “performance art act of juvenile Id-fulfillment”-- and intoning dialogue corny enough to embarrass even William Shatner. (It’s Leonard Nimoy’s voice however, heard coming out of that mean ol’ Sentinel Prime.) I enjoyed the first Transformers (on DVD) and passed on the second one, so this is the first one I’ve seen in, shall we say, full bloom, projected in 3D, and elements of it are astonishing. The sheer aggressive force of the last hour, in which Chicago is laid waste by the evil Decepticons, is something like awesome (and exhausting) to behold. In addition to the usual clunky-but-way-limber metalloid bad guys, there’s a subterranean multi-tentacled robot that burrows through Michigan Avenue like it was made of butter; this creature is one of the scariest monsters I’ve ever seen and might even give the notoriously anti-CGI Ray Harryhausen fits of envy. Director Michael Bay justifies his own loopy gigantism with his use of 3D here to not just create things what pop out at ya, but also a vertiginous depth of field that lends stomach-churning realism to the movie, particularly to a sequence involving a ragtag group of commandos paragliding into the city, plummeting down into and amongst the crumbling, smoking skyscrapers. And speaking of skyscrapers, the outrageous sequence of a multi-story office building being scissored in half while our heroes are still inside plays like the greatest Irwin Allen movie never made. My only complaint is that Shia LeBouf manages to make it out alive. Otherwise, it’s the humans, man. Transformers, DOTM manages to get plenty of juice from Bay’s near-self-parodic tone, especially in the first half, courtesy of actors like Frances McDormand, John Turturro (resplendently weird), John Malkovich (giving Turturro a run for his money in the weird department), and even the close-to-overexposed Ken Jeong, who seems always ready to wrest away Most Specious Racial Stereotyping honors away from the estimable Geddy Watanabe, here getting loads of crass laffs as a paranoid scientist who assaults LaBouf in a men’s room. Yes, I enjoyed Transformers: Dark of the Moon, but it made me want to see a season of Yazujiro Ozu movies as penance, as necessary therapy.

Best in class honors for the blockbuster superhero genre thus far would go to two other Marvel creations—the splendid prequel X-Men: First Class, directed by Matthew Vaughn (Kick-Ass) and Joe Johnston’s visually sublime Captain America: The First Avenger. The X-Men prequel jettisons hoary old Patrick Stewart (Mr. X) and Ian McKellan (Magneto) for supercharged younger versions in the personage of James McAvoy and Michael Fassbender, respectively, and the trade-in is a good one. Both actors suggest the reserve of pain, anger and dignity brought to the parts by their predecessors, as well as the fire and energy to keep the franchise alive over two or three more episodes. The element that makes that a tantalizing prospect is the way XMFC cheekily injects its heroes and their nascent band of mutant followers (including recent Oscar nominee Jennifer Lawrence as Raven, the girl who will grow up to become Rebecca Romijn’s Mystique) not only into the history of Nazi atrocities in World War II, but also as unlikely players in the Cuban Missile Crisis. One can imagine the fun Vaughn, with fellow screenwriters Ashley Miller, Zack Stentz and Jane Goldman, might have plundering the history books to find more sticky real-world situations in which to figure this philosophically opposed band of mutant heroes, hopefully with as much Bondian panache as X-Men: First Class manages to muster.

Captain America, on the other hand, is a rousing, straight-arrow adventure and a showcase for the classical filmmaking strengths of director Joe Johnston. Like his previous outing in period superhero adventure, The Rocketeer, Johnston makes the most of the gleaming retro-futuristic set design (what forward thinkers in the 1940s might have imagined for Things to Come), and he has a penchant for pacing and editing this kind of movie that might make him come across as slightly doddering to audiences expecting more cuts per minute and fewer stop-downs for actual conversation. This kind of approach seeps into the sensibilities of the actors too, not a wink or a nudge to be found among them. Chris Evans, who might have been expected to wear some snark on his sleeve, occupies Steve Rogers (especially his shrunken, slight-framed pre-transformation incarnation) with admirable sincerity (though I will concede he, or the screenplay, doesn’t do as much with his adjustment to those rippling pecs as one might hope). Crisp and lovely Hayley Atwell provides both romantic and moral interest as a British intelligence officer, while Dominic Cooper (as Tony Stark’s dad, Howard) and Tommy Lee Jones as the army colonel who questions whether Rogers has the stuff to be Captain America, provide our hero’s military support. And as Colonel Johann Schmidt, aka Red Skull, Hugo Weaving demonstrates once again, relishing each villainous bon mot as if it were filet mignon, why all future bad guy roles should automatically go to him. (I also loved Toby Jones as his brilliant henchman, a scientist who cannot hold back the dawning horror of what his boss is really up to from flashing across his face.) Ultimately, the movie manages to demonstrate the dollars spent on its surely enormous budget while at the same time seeming considerably down-scale in its urge to bowl us over with giant set piece after giant set piece. Johnston knows the value of restraint, of delayed gratification, and in Captain America he demonstrates the principles with gleeful ease. In the process he’s crafted a modern superhero movie that, like its titular character, looks entirely capable of standing the test of time.

As for those wizard kids, turns out everything’s going to be all right. After last year’s lugubrious Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, which seemed like agreeable filler at best (absent the addictive ritual of the seasonal Hogwarts arrival and all the attendant fun), it was a great relief to see everything wrapped up so expertly, so emotionally, in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2. I was indifferent to the series all the way up through the release of The Half-Blood Prince (part 6), having seen part one on DVD months after the fact, and only parts 2 and 3 theatrically. But part 6 was so good that I was compelled to go back and watch the series in its entirety, excellent prep as it turned out for the emotional grandeur of the finale. Everyone has their great moment here, including Maggie Smith, Helena Bonham Carter, Daniel Radcliffe, Ralph Fiennes and, I think most importantly, Alan Richman whose Severus Snape becomes, with this closing chapter, one of the great misunderstood villains of all. (An Oscar nomination for him here would be the right thing to do.)

Just as anticipated (certainly by the girls in my family) as Harry’s Last Stand, was Super 8. The movie stands primarily as a heartfelt valentine not so much to a more innocent time of childhood, but specifically a heartfelt valentine to childhood as seen through the prism of Steven Spielberg, whose own films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. The Extra-terrestrial documented a version of childhood for a generation of movie-fed kids, like Spielberg himself and Super 8 director J.J. Abrams. What’s genuinely wonderful about Super 8 is the way it captures the knockabout obsessive creativity of kids making their own movie (the title refers to the consumer-grade film stock on which most of those movies in the late ‘70s were made) as they careen about in a universe made up almost entirely of Spielbergian tropes, situations and camera moves. The kids witness and accidentally film the Train Accident to End All Train Accidents while shooting a nighttime scene at a railroad station. The shooting of that scene reveals as much, if not more, about kids’ fragile relationships than the Spielberg pictures it has in its rear-view mirror ever did. (Elle Fanning as the lone female in the group has a moment rehearsing her part in the movie-within-the-movie as the detective’s put-upon wife that is as revelatory as Naomi Watts’ shocking audition in Mulholland Dr.)

What was actually on the train is a mystery the kids, and the movie, begin to focus on, but unfortunately Super 8 never makes the kids and their moviemaking an integral, organic part of solving that mystery, even when it turns out that the camera has been left running and has captured what looks like an alien leg emerging from an overturned train car. Had writer-director Abrams ever been able to figure out a way to make their movie genuinely important to his movie, as something other than a nostalgic nod to his own creative past, Super 8 might have been genuinely great, and it might have figured out a way to avoid the slightly generic feeling that begins to settle in as the movie makes the rush toward its overly familiar conclusion. That said, there’s so much on a human scale to be excited about in Super 8 that its flaws, its overt genuflecting in the direction of Spielberg, becomes almost endearing, or at least an emblem of its good intentions. I saw it in two low-tech situations—a drive in, and then a nondescript cracker-box four-plex in Big Bear, both of which greatly resembled the venues in which I saw the original Spielberg films being referenced here, so there was an added extra layer of meta-nostalgia in Super 8 for me. My oldest daughter, on the other hand, loved the movie so much that she stood up at the drive-in and excitedly proclaimed that “This is the best movie I’ve ever seen!” And that was only at the midway point. The most wonderful thing is that now, inspired by Super 8 and by seeing some of my own old super 8 movies, she and her friends have embarked on the adventure of writing a script and making their own movie this summer. Now, that’s a filmmaking tradition worth celebrating.

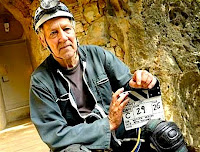

There have been other adventures at the movies as well. My hopes for Monte Hellman’s return to filmmaking with The Road to Nowhere were dashed pretty quickly. The movie, a meta-concoction mixing murder on the set of a Hollywood thriller with the mind games of The Stunt Man, The French Lieutenant’s Woman and a hundred other similarly-themed indie features over the past 20 years, collapses under the weight of its flimsy, self-conscious conceits. It’s a sadly misconceived hall-of-mirrors puzzle play done in by indifferent acting and an ugly DIY mise-en-scene. A better time was had when my girls and I went spelunking with Werner Herzog in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the director’s mesmerizing 3D document of the Chauvet caves of Southern France, in which reside the oldest known man-made drawings. The kids were at turns riveted and bored by Herzog’s methodical approach, but two wonderful things emerged from the experience, both courtesy of my eight-year-old. She has now developed a hilarious Herzog impersonation in which she quotes the director’s narration about a group of albino crocodiles in a nearby biosphere, adopting her very best Teutonic drawl: “"They had lots of room in which to thrive... and man, did they thrive!" And after the movie, she asked me, in reference to one of Herzog’s claims in the movie that the drawings represent man’s very first toying with the idea of representing movement in pictures, “Daddy, what is proto-zinneeema?” Worth the price of admission for those two moments alone, not to mention the sundry other marvels Herzog’s terrific documentary lays out for us.

There have been other adventures at the movies as well. My hopes for Monte Hellman’s return to filmmaking with The Road to Nowhere were dashed pretty quickly. The movie, a meta-concoction mixing murder on the set of a Hollywood thriller with the mind games of The Stunt Man, The French Lieutenant’s Woman and a hundred other similarly-themed indie features over the past 20 years, collapses under the weight of its flimsy, self-conscious conceits. It’s a sadly misconceived hall-of-mirrors puzzle play done in by indifferent acting and an ugly DIY mise-en-scene. A better time was had when my girls and I went spelunking with Werner Herzog in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the director’s mesmerizing 3D document of the Chauvet caves of Southern France, in which reside the oldest known man-made drawings. The kids were at turns riveted and bored by Herzog’s methodical approach, but two wonderful things emerged from the experience, both courtesy of my eight-year-old. She has now developed a hilarious Herzog impersonation in which she quotes the director’s narration about a group of albino crocodiles in a nearby biosphere, adopting her very best Teutonic drawl: “"They had lots of room in which to thrive... and man, did they thrive!" And after the movie, she asked me, in reference to one of Herzog’s claims in the movie that the drawings represent man’s very first toying with the idea of representing movement in pictures, “Daddy, what is proto-zinneeema?” Worth the price of admission for those two moments alone, not to mention the sundry other marvels Herzog’s terrific documentary lays out for us.

Finally, after much hemming and hawing and distraction and excuse-making, I made time to see Terence Malick’s The Tree of Life last night and, frankly, as someone who has admired Malick's past movies, I was curiously underwhelmed. Maybe it was because the director felt compelled to go after the big statement, to try to sum up all of the ways of looking at the world that have been encompassed by his other movies. And maybe it was because he’s hitched his cosmic point of view to a series of moments stitched together from memories of growing up in rural Texas in the ‘50s. The problem for me is, that summation seems unnecessary; he’s already dealt with issues of nature, the origins of life and the nature of nature compellingly in Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line and The New World, only without eschewing the possibility of dramatic involvement, which is the lifeline that gets cast away here pretty quickly. Visually the movie is full of poetic, sometimes unexpected imagery (including the way those images attach to one another in Malick’s intuitive, weirdly-wired editing). And I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a movie more intoxicated with the magic hour. It’s as if the entirety of Malick’s memory of childhood were composed of idyllic shots of his idealized mother (Jessica Chastain, who does little else but worry and glow) twirling in the backyard, or a preoccupied dad (Brad Pitt) shouldering the weight of existence in between playful squirts of Eden’s garden hose, while their three boys wander aimlessly, happily through a rural paradise, all lit by a setting sun as they await the arrival of the serpent. There is also an astonishing sequence in which the oldest boy’s growing up amongst his two younger siblings is compressed into a beautiful visual essay about the way a child might see the surrounding world. It is with this gaze that Malick most clearly relates.

But I don't know, if this movie were the only evidence, that I'd say Malick is a visually brilliant filmmaker. To me that phrase is meant to describe someone who knows how to marshal the power of images, not just as individual creations, but as pieces of a whole, or as a philosophy of design or, most important, the curiously undeniable urge to tell a story. It's when the images add up to something other than a director's microscopic, fleeting attention to the minutiae of the world around him that I start to sit up and pay attention. In my mind this standard can apply to directors as disparate as Don Siegel, Jean Renoir and Vicente Minnelli, to name just a couple off the top of my head, but not, at least in the first 24 hours after having seen it, to the Malick of The Tree of Life. I've been trying to figure out how to deal with my reaction to the movie, which obviously many others loved, without betraying my own disappointment and pretending to be more impressed, or throwing everyone I respect who holds it in high esteem under the pretentiousness bus. I wrote earlier this year that I would distrust anyone’s instant proclamation of The Tree of Life as an unqualified masterpiece (and there have been many of those claims, right straight out of the movie's Palme D’Or –winning showing at Cannes) as much as I would anyone who insisted upon rejecting it out of hand. Mine is certainly an amorphous, immediate reaction too; maybe in three months my memories of it will coalesce into a movie I can’t wait to see again. Stranger things have happened. But right now I’m dealing with a vaguely depressed feeling, and I can’t decide if that’s due to a sense that I’m missing out on something, or if it’s simply a disappointed feeling for a filmmaker who has this time out, in my view, shot way wide of his intended cosmic target.

The halftime show is over. Onward to the second half.

***************************************************