THE "FIGHT FOR 35mm" CONTINUES

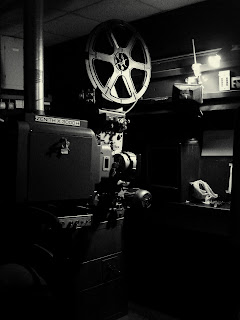

The fight to keep 35mm print production from disappearing continues. On November 15 Julia Marchese, one of the faces you see every time you buy a ticket to see a movie (projected in 35mm) at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, posted an online petition in support of resistance to the apparently inexorable industry movement toward the elimination of traditional 35mm prints for theatrical exhibition. For Marchese, and for many who attend the theater regularly, the concern goes beyond a mere question of technology. “The human touch will be entirely taken away,” she writes in the petition’s statement, and then goes on:

“The New Beverly Cinema tries our hardest to be a timeless establishment that represents the best that the art of cinema has to offer. We want to remain a haven where true film lovers can watch a film as it was meant to be seen — in 35mm. Revival houses perform an undeniable service to movie watchers — a chance to watch films with an audience that would otherwise only be available for home viewing. Film is meant to be a communal experience, and nothing can surpass watching a film with a receptive audience, in a cinema, projected from a film print.”

So far, after not quite 15 days, the petition has gathered upward of 5,300 “signatures,” just over halfway to the intended goal of 10,000, at which point the petition would presumably find its way to the desks of Those It May Concern at the various studios, all of whom will be free to consider the passion behind it or disregard the petition as a blip of protest from a minority of selfish Luddites who refuse to understand and accede to the inevitable march of progress.

And that progress does indeed march on. As Jen Yamato reported in her piece for Movieline on the downshift in 35mm print production, studios like 20th Century Fox have already begun movement in some Asian markets to phase out distribution of 35mm prints to theaters in favor of an all-digital exhibition format. She quotes Fox International’s Sunder Kimatrai as having said, back in August of this year, that “the entire Asia-Pacific region has been rapidly deploying digital cinema systems” and that “over the next two years we expect to be announcing additional markets where supply of 35mm will be phased out.” And if that isn’t convincing enough, John Filian, president of the National Association of Theater Owners, had this rather definitive statement to deliver in his annual state of the industry address to attendees of Cinecom, NATO’s inaugural convention gathering in Las Vegas back in March 2011:

And that progress does indeed march on. As Jen Yamato reported in her piece for Movieline on the downshift in 35mm print production, studios like 20th Century Fox have already begun movement in some Asian markets to phase out distribution of 35mm prints to theaters in favor of an all-digital exhibition format. She quotes Fox International’s Sunder Kimatrai as having said, back in August of this year, that “the entire Asia-Pacific region has been rapidly deploying digital cinema systems” and that “over the next two years we expect to be announcing additional markets where supply of 35mm will be phased out.” And if that isn’t convincing enough, John Filian, president of the National Association of Theater Owners, had this rather definitive statement to deliver in his annual state of the industry address to attendees of Cinecom, NATO’s inaugural convention gathering in Las Vegas back in March 2011:“Based on our assessment of the roll-out schedule and our conversations with our distribution partners, I believe that film prints could be unavailable as early as the end of 2013. Simply put, if you don’t make the decision to get on the digital train soon, you will be making the decision to get out of the business.”

What else needs to be said, right? In the face of a digital tide like this one, the complaints of 10,000 folks who claim to care about the aesthetic difference between 35mm and digital projection are likely to have the cumulative amplification akin to the tiny residents of Whoville shouting at the top of their lungs from a speck of dust while dangling over a vat of boiling oil. The dire implications that the elimination of 35mm prints will have for the very concept of revival cinema, which is already withering in the face of the explosion of new media options for watching films, likely won’t amount to much more than a hill of beans to studios who, if history can be trusted, can’t be expected to be concerned about much more than their own financial solvency and the practical expediency of the digital conveyance of their product.

And the importance of that practical expediency extends not only to the owners of revival houses, who are faced with the very real possibility of the flow of available product for their specific programming needs being shut off at the spigot, but also to the owners of those small town movie houses in rural areas far outside the immediate dollar-sign-impeded gaze of the studios. I’ve spoken to several owners of theaters in rural areas of California and Oregon in the past year, many of whose theaters are operating at a near-zero profit margin on equipment that was outdated 30 years ago, who have all worried to me openly about the increasing cost of rentals as well as the specter of being put out of business by a industry-wide switch to digital that they can’t afford to make. Last Picture Show-like images of shuttered hometown movie theaters all across the country are already too prevalent, and a forced paradigm of digital conversion is likely to ensure that the rural landscape will be dotted with even more corpses of once-vital movie palaces that will have been abandoned not only by audiences in favor of the cozy confines of their home theater systems, but also by the very studios whose product they still sought to present to the few who still cared to buy a ticket.

Suppose it were desirous and within the budget of a theater like the New Beverly Cinema to proceed with the conversion to digital projection, even one in which the current 35mm film projection system could be maintained. The viability of a theater like this would still depend on the availability of 35mmand digital access to those vast film libraries, which, even if they continued to exist at their current volume, are likely to become even less available to small exhibitors as the economic viability of dealing in “niche” programming becomes increasingly devalued. Sure, it makes sense for studios to keep their claws on existing 35mm prints now, because there’s still a shekel or two to be squeezed from their existence in the marketplace. But once these geniuses, all foresight and no historical perspective, become convinced of the economic righteousness and solidarity of the move to digital that they initiated, it’s not hard to imagine the ascension of an even more cavalier attitude toward keeping those expensive underground vaults (and the staff required to maintain them) occupied with such an anachronistic duty as preserving film history on quaint, outdated chemical film stock.

After all, 35mm film decomposes, but digital is forever, right? Well, the answer to that ostensibly rhetorical question is, um, not quite. Arthur Wehrhahn, spokesman for the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center, which recently participated with Turner Classic Movies in a festival presentation of 14 restored films, has felt the need to make crucial clarifications on the subject. In a piece written for the Museum of Modern Art’s Inside Out blog in March 2011, Wehrhahn expressed concern about the way digital is frequently perceived as a magical solution to issues surrounding film preservation:

“In this era of digital storage and viewing of moving image materials and films, I’m sometimes afraid that the public at large will think that the problems of preserving films have all been solved—or worse, rendered irrelevant. I feel this most acutely when I speak with younger people, from schoolchildren to 20-somethings, and they’re stunned when they realize that we have to preserve and protect film materials. I find myself explaining that, despite every new wonder of electronics or digital format that comes along, the best source material for older works is still the film itself.”

(See Wehrhahn’s video presentation by clicking here.)

Yet production of 35mm films, for archives and for rentals, remains an increasingly low priority for the studios. As I said in my own response to Yamato’s piece on Movieline, when we've finally done away with 35mm projection in revival houses that rely on these vaults for programming, is it so far-fetched to imagine those same penny-pinching studios citing economics as an excuse for not making available all but the most "popular" classic film titles? In the near future, in the name of short-sighted number-crunching, a double feature of 99 River Street and The Blue Dahlia at a place like the New Beverly will be a long-forgotten pleasure, with only Turner Classic Movies to remind us of the theaters and the programs we once took for granted.

Not everyone is convinced that going digital is necessarily all that bad an idea however. Friends and acquaintances of mine who live in small-to-medium-sized markets outside of major cities in California and New York, where the issue of revival cinema is moot, are pleased as punch to see the spiffy, bright, crud-free imagery that conversion to digital brings to their stadium-seating-style multiplexes, and to the crappy cracker-box cinemas that have limped along without much change since the ‘80s. (Whether they remain equally pleased by the same 10-15 movies that will be available at these mainstream movie houses is another question, one with which most moviegoers are well familiar.) But even some who have access to great revival programs like those available in Los Angeles and Austin, Texas are unconvinced that the potential loss of 35mm exhibition is all that significant. Yamato’s piece inspired several passionate comments, like this one from “Sunnydaze”:

Not everyone is convinced that going digital is necessarily all that bad an idea however. Friends and acquaintances of mine who live in small-to-medium-sized markets outside of major cities in California and New York, where the issue of revival cinema is moot, are pleased as punch to see the spiffy, bright, crud-free imagery that conversion to digital brings to their stadium-seating-style multiplexes, and to the crappy cracker-box cinemas that have limped along without much change since the ‘80s. (Whether they remain equally pleased by the same 10-15 movies that will be available at these mainstream movie houses is another question, one with which most moviegoers are well familiar.) But even some who have access to great revival programs like those available in Los Angeles and Austin, Texas are unconvinced that the potential loss of 35mm exhibition is all that significant. Yamato’s piece inspired several passionate comments, like this one from “Sunnydaze”: “I love the New Beverly and have some great memories. One being when I saw Kubrick's The Killing and realized while watching with an audience that it is a comedy. But the experience would have been the same had it been digitally projected. The audience was what made the difference, not actual film.”

And this from a respondent named “Joshua”:

“Audiences aren't there to see how much money is being saved and if they can tell the difference between digital and print, they don't care.”

Finally, a reader going by the handle “Rainestorm” seemed to most calmly and tersely drive in the final, arguably inarguable point in the debate by leading off his response with this statement:

“Film exhibition is dead. It's been dead for years and people have been selfishly and cruelly keeping it on life support rather than letting it move on. Sentimentality for dead technology is fine as long as you're the one footing the bill. Asking someone else to keep it breathing just for you is ridiculous…. Seems as though this outcry is misplaced.”

Realistically, it does seem to be asking a bit too much of a corporate-owned studio to suddenly develop a sensitivity to concerns that are more convincingly couched in arguments based on sentiment than on dollars. Yamato herself admits in the piece that the plea for preservation of 35mm is largely sentimental and not practical. But she goes on to make an important point about film culture as it exists in the Internet age where metropolitan revival and repertory cinemas serve to provide support for studio catalog sales on home video and pay-per-view in markets that reach far beyond those urban epicenters. “If a curious neophyte without access to local revival houses downloads a classic film onto their iPod because they read a blog about a screening halfway across the country or the world,” Yamato asks, “hasn’t repertory cinema done its part?”

In fact, the most potent outcry is one that is based not on aesthetic preference but on preservation of cinema history, and there is no compelling reason why art and commerce need necessarily be at odds here. Reader Ant Timpson points out that there even seems to be little economic sense for studios to resist continuing to strike archival prints designated specifically for revival programming. “They'd make their money back within the first 20 bookings,” Timpson argues, not to mention holding cultural value in the cause for preservation. But it’s no comfort for film fans if it’s left up to almighty market demand instead of historical or artistic worth to determine which titles the studios deem worthy of preserving on 35mm, from where shall come further digital copies. Only the titles that have been determined to be the most commercially viable are likely to be available in digital formats, thus limiting what can be shown in cinemas and exposed to future generations. For these films to mean anything to anyone down the road, is it not crucial that people be able to at least have the option to see them in environments considerably more enveloping, and less distracting, than their living rooms or on airplanes? Comparing the dollars-and-cents cost of actual preservation to the cost of the loss of these films in terms of cultural heritage, it seems that one is (or ought to be) far more heavily weighted than the other.

In fact, the most potent outcry is one that is based not on aesthetic preference but on preservation of cinema history, and there is no compelling reason why art and commerce need necessarily be at odds here. Reader Ant Timpson points out that there even seems to be little economic sense for studios to resist continuing to strike archival prints designated specifically for revival programming. “They'd make their money back within the first 20 bookings,” Timpson argues, not to mention holding cultural value in the cause for preservation. But it’s no comfort for film fans if it’s left up to almighty market demand instead of historical or artistic worth to determine which titles the studios deem worthy of preserving on 35mm, from where shall come further digital copies. Only the titles that have been determined to be the most commercially viable are likely to be available in digital formats, thus limiting what can be shown in cinemas and exposed to future generations. For these films to mean anything to anyone down the road, is it not crucial that people be able to at least have the option to see them in environments considerably more enveloping, and less distracting, than their living rooms or on airplanes? Comparing the dollars-and-cents cost of actual preservation to the cost of the loss of these films in terms of cultural heritage, it seems that one is (or ought to be) far more heavily weighted than the other.Even so, one suspects that the point of view of Rainestorm, again expressing her/his thoughts in the comments thread beneath Yamato’s original piece, is not in the minority, certainly not from a studio perspective, and maybe not even from the audience’s. “This is the old art versus commerce argument and commerce will always win, as it should,” she/he writes, and then continues:

“Commerce is a reflection of artistic merit and popularity. After all, if only a small minority declare something to be art, does that make it so? That, too, is an old argument. Not every book that's been written, not every song that's been sung, not every piece of art that has ever been created or viewed has been preserved.... and that's how it should be. Too much variety has the undesired side-effect of diluting even the most meritorious work of art.”

Forgive me if I say that this rather strident pronouncement sounds a lot like the wolf of cultural elitism hidden under a populist sheepskin. In an art form where art and commerce have always coexisted uneasily, why exactly is it that it should be so that commerce wins the argument between the two? Because the concerns of those who stand to make money off of a work of art, or a work of simple entertainment, are so much more important than those who created it, who attempt to preserve it, who insist upon its original, intended form? Of course monetary concerns must be considered. But we live in an increasingly greedy world of Hollywood product, where a nonsensical business model has created a “Can you top this?” mentality of blockbuster filmmaking in which modest aims are often drowned amidst the crashing waves of bloated, attention-grabbing, lowest common denominator hubris. Why is it that the short-sighted financial aims of studios, in perpetual genuflection toward Mammon, have taken precedence over a movement to preserve a vital part of film history that would, in comparison, demand but a pittance? Surely these efforts comprise but a fraction of the budget of a studio holy grail like the digitally gratuitous Transformers franchise, each sequel costing more and demanding more in order to perpetuate the escalating model of excess, each sequel crowding out smaller, perhaps worthier films in the marketplace and now, apparently, crowding out the studio’s own history as well.

I would certainly agree that it is not enough to qualify a piece of work as art if only a small minority says it to be so. (The writer makes sure to point out that this too is an “old” argument, as if to imply that it having simply been expressed already is evidence of its invalidity.) On any visit to any museum in the country, or to any film festival you care to attend, you ought to find yourself surrounded with paintings and sculptures and films that do not, despite their endorsement by the museum or the programming staff, qualify as either masterpieces or even art. But as obvious as it may be that a simple minority proclamation toward art is not evidence of the actual thing, we must also hold in skepticism that proclamation’s opposite, that because a work or a movement has the ringing endorsement of the majority, as expressed in ticket sales or dollars spent to create and distribute it, we should automatically give it the benefit of the doubt in the argument over validation via commerce versus art any more than we would be quick to bestow the imprimatur of art upon an unworthy subject.

Rainestorm then goes on to suggest a sort of law of natural selection as it might unreasonably apply to the stewardship of film culture. It sounds pretty self-assured to proclaim on behalf of everyone that “not every book that's been written, not every song that's been sung, not every piece of art that has ever been created or viewed has been preserved.... and that's how it should be.” Such a cavalier response to the vagaries of the history of all arts again smacks of an elitism that suggests that only certain works of art are even worth the effort of preservation. Are we to leave preservation to the whims of chance? Of ambition (or lack thereof)? And if the effort to preserve is to be undertaken, who is it that decides which works are art and whether or not they should be well kept or simply discarded? These are questions that are best left unconsidered if you’re rushing to make a statement like, “Too much variety has the undesired side-effect of diluting even the most meritorious work of art.” Isn’t this attitude precisely the opposite of the one taken by most film preservationist movements?

The attitude of film preservation has at its core the notion that every bit of film that can be saved from any era has its worth, its value, its important historical context. I was lucky enough to see a largely forgotten Warner Brothers-Vitaphone picture from 1932 the other night, an ensemble comedy-drama from 1932 called Central Park. No one has fallen all over themselves rushing to make great claims for this John G. Adolfi–directed picture as a work of art. But it has got a lot of the fizz and pop one expects from early Warner Brothers talkies, as well as some anthropologically appealing footage of Central Park and New York City as it existed during filming, the kind of footage probably once thought of as disposable, without value, and of increasing interest the further we pull away from that period of history. And it also has plenty of evidence of the seductive star power of Joan Blondell, who never carried her Photoplay popularity to the great heights one might have reasonably expected, given the effortless charm she displays in this movie. Are we to blindly accept the queasy proposition that it’s okay if a movie like Central Park falls to the wayside and gets trampled into silver nitrate dust by history just because to have it out there makes it more difficult for the masses and the historians and critics to discern art for all the multitude of choices diluting our sensibilities?

Thank you very much, but I’d at least like to have all the historical evidence before me in order to be able to decide for myself. That’s why film preservation, and the continued availability on 35mm of even the most marginal films from any era, studio or country, is important, for the sake of film history and encouraging further generations to appreciate that history, as well as the continued survival and health of venues like the New Beverly Cinema, the Cinefamily, the American Cinematheque, the Alamo Drafthouse, the Film Forum and all the other houses dedicated to presenting the full spectrum of cinematic art and entertainment. The effort to preserve 35mm as at least a viable option in the increasingly digital 21st century may be a sentimental, selfish impulse, but it is also one that places value on something other than the instant gratification of profit, a goal of greed that is even more fleeting than the chemical composition of that precious celluloid. It’s one that believes wholeheartedly, simply, in the audience’s sensitivity and receptivity to the movies as an art form.

Pauline Kael, in her 1974 essay “On the Future of Movies,” wrote the following, and it’s worth considering in light of the possible future of 35mm film distribution:

“Perhaps no work of art is possible without belief in the audience—the kind of belief that has nothing to do with the facts and figures about what people actually buy or enjoy but comes out of the individual artist’s absolute conviction that only the best he can do is fit to be offered to others… An artist’s sense of honor is founded on the honor due others. Honor in the arts—and in show business too—is giving of one’s utmost, even if the audience does not appear to know the difference , even if the audience shows every sign of preferring something easy, cheap and synthetic. The audience one must believe in is the great audience; the audience one was part of as a child, when one first began to respond to great work—the audience one is still part of.”

You can keep the momentum going by signing Julia Marchese’s “Fight for 35mm” petition right here.

********************************************

13 comments:

Wonderful, insightful, thought provoking and yet still clouded. As always Dennis....marvelous!!

Thanks, DID. Don't know what to do about the clouded part other than shine a little light on those voices who don't appreciate the road we're being led down on concerning this issue.

I'd love the chance to see Central Park. The big lesson I've leaned in over forty years of cinephilia is that you can't outguess what's important and why in film history, which is why it is all worth saving. And yes, some of the films are of value simply because they give a glimpse as to how people lived at a certain time and place.

By the way, I saw Joe Dante's Matinee last Sunday, and a shot near the end, of the projector being turned off. was especially poignant.

I'm not going to pretend like my interest in maintaining 35mm (or any other size of celluloid) doesn't come, at heart, from a selfish place - after all, I'm only 25, have theoretically decades of attendance at the New Bev, Cinefamily, etc. ahead of me, and would very much not like to see that cut off, or even degraded.

Obviously that could perhaps continue under the digital domain, but the cost, I think, is greater than one of the joy of celluloid. Even if every film that sits in every vault does get scanned, then what? That's it? A 4k, MAYBE 8k scan is the best we've got? For how long? I know it seems silly now to say that an 8k scan isn't good enough, but less than ten years ago we were all marveling at 1080p. Standards change.

And I do worry about preservation in the digital era. Everything SEEMS to last forever right now because we're really only fifteen or so years into the digital revolution (in terms of its impact on and acceptance in mainstream culture). We really don't know how file formats will change, how data can be corrupted, etc.

And that last part worries me the most - my first viewings of Picnic at Hanging Rock and Edward Scissorhands were through awful prints full of scratches and missing frames. I still loved both. I recently attended AFI Fest, and a screening of Restless City had to be interrupted and restarted because the digital file kept "skipping". That instance was far more distracting than even the worst damage I've endured with any film print. AFI was fortunate enough to have another deck on hand, but what of theaters that don't?

And as much as I'd still pay to see great films with crowds, in the end, you're essentially paying for image quality you can get at home.

I wonder if the solution lies in the tax code. Offer incentives in the form of tax deductions to the film companies for money spent on preservation, with the requirement that the films preserved must be made available for use by museums and colleges for educational purposes. ("Central Park," for example, could be part of a series showing how New York looked in the 1920s and '30s.) That would provide the enlightened self-interest needed for the film companies to assume the cost of preservation. Certainly their lobby has the oomph needed to get a relatively minor item like this tucked deep inside some bill.

Though so much of this post is dedicated to tearing about Rainestorm's comments, I don't think they were completely off the mark when they wrote "Sentimentality for dead technology is fine as long as you're the one footing the bill. Asking someone else to keep it breathing just for you is ridiculous." It's a bit to bitterly phrased for my taste, but it's not wrong.

Studios are corporations. As such, they see as their primary jobs (1) making money and (2) making new product - not preserving culture. When they keep well-cared-for archives, when they go out of their way to make sure that projection prints of their back catalogs exist - those are bonuses and blessings. This is how it's always been - this is part of why so many films from the first half of the 20th century are lost, for example. Begging them to "save 35mm" just seems misguided.

So, rather than quixotically trying to persuade the studios to "do something" - which seems unlikely, given how much they've invested in the switch to digital and given how capitalism works (at least in the 21st century - let's not forget that cinema itself is an expression of how it worked in the 20th) - I hope that the signers of Marchese's petition will do something substantial on their own.

Like, programmers and venues who care about screening repertory films on film should acquire - and care for - projection prints that they think should be exhibited, so that they will always have film to show. (There are cinemas that are already doing this, Cinefamily, Doc Films, and my own home organization among them). They should make sure that their projectionists always handle film like it's priceless - even if that means paying them like skilled rather than menial labor so that they can keep experienced people around. People with money should consider making donations to film archives with the provision that they would like their money to go to support the preservation and circulation of 35mm prints, not toward digitization. People with energy should explore the possibility of acquiring some space and some lab equipment from one of the many film labs that have gone under in the last year or two and try to get some old lab employees to teach them what they know before they disappear (not sure if this is actually a feasible plan, but at the very least the lab work end of this whole issue is something that needs more attention). People who want to make films and care about 35mm (or 16mm, or 8mm...) should do their part to support the industrial infrastructure that allows filmstock to exist and shoot on film, even if it's expensive - it's not going to keep existing (or being affordable, for individuals or for archives doing preservation work) without a market for it. Everyone should talk to everyone they know who isn't thinking about this stuff and might care, and try to convince them to (they'd care if it was a matter of art museums deciding to only ever show paintings in reproduction just so they could save on paying the union art handlers, right?)

Not to say that a petition can't be part of this potential flurry of action! But there are a billion things that people who care about 35mm and other filmstocks can do ourselves - without groveling before the studios - to help the cause.

Dennis: I read this over my lunch break, and each time I thought, "Well, wait, you're missing X," you'd come along and deal with it. Thorough to the end!

Thus, some of this covers stuff you've already covered, but nevertheless a few thoughts that I had while reading this:

* I'm fortunate enough to have seen Lawrence of Arabia in 70mm. But the thrill was seeing it on the big screen, not the celluloid. I won't begin to argue that film and digital look different (never mind if it was shot on film or digital), but the difference is negligible, and to suggest otherwise is a silly argument from anyone with a DVD collection. We've all been happily consuming digital for a long time, and it weakens our ability to argue for the necessity of film from an aesthetic perspective.

* Thus, we need to preserve film to preserve history -- in the name of history and art. It's true, of course, that not all art has lasted. But the reason so much art hasn't lasted has nothing to do with its greatness or popularity so much as whether the country of the artist was in power or annihilated in war. The beautiful thing about film is that, while so much has been lost already, the art form is young enough and civilization and technology have advanced enough to make the thought of preserving almost all of film history to seem not totally impossible (at least until global warming kicks all our asses, in which case never mind). From that perspective, film is unique, and so we should cherish the rare opportunity to preserve everything that's out there, rather than deciding it's expendable just because all of literature, music, sculpture, etc., couldn't possibly have been collected for all time. (BTW, your Central Park example is a great one, also because it made me think of the so many films to include the World Trade Center towers that suddenly took on new importance after 9/11.)

* We should fight to preserve film, at least what film exists, purely for archival purposes and simply because we can and because it's the right thing to do. We do things like that all the time. It's not a novel concept.

* I feel for any theater that might not be able to afford a switch to digital, but this is the way of the world. Many of those struggling cinemas stand there because some other business folded on the same footprint before cinema's time. It depresses me to see abandoned theaters. But it also depresses me to see sold-out theaters full of people who can't sit for a two hour movie without checking Facebook.

Peter, Scott, Becca, wwolfe, Jason:

No time to respond to all the wise words you've offered right now other than just to say that I am very happy to see all of your thoughtful and well considered comments under this post.

Thank you all most sincerely for taking the time to elaborate of points I made, challenge others, and oftentimes elucidate angles on the issue I completely missed. I hope I can return to all these comments and respond more thoroughly soon!

“I love the New Beverly and have some great memories. One being when I saw Kubrick's The Killing and realized while watching with an audience that it is a comedy. But the experience would have been the same had it been digitally projected. The audience was what made the difference, not actual film.”

====================

Oh good lord.

A bunch of yahoos laughing at a serious film about a robbery gone bad does not make it a comedy. Remember, stupid people laugh at things they don't understand.

--t

Scrolls gave way to books. Vinyls gave way to cds. Film will give way to digitalized images. A movie is ultimatley not what in the film but what's on the screen.

It's too bad movies weren't digital from the beginning. If it had been, most early movies would still remain us with us. But because they're printed in fragile film, 90% of early cinema has been lost forever.

"Vinyls gave way to cds."

Some would say that's not a good thing, either.

Thanks for the post, Dennis - easily the best and most balanced rundown I've seen of a really murky issue.

Perhaps most do not realize this, but when you watch movies on DVD or VHS or TV in general, the brain is not as engaged as it should be. When you watch a film, in the theater, projected through celluloid at 24 frames per minute, your mind is the object that's really creating the illusion of movement. You see a picture, and a picture, and a picture, 24 times a second, and your brain makes the connection between all of those little still pictures, and is thus automatically always engaged, and thus transported. Mind you, this goes for all films that are projected in this way. This adventure is what we pay big money to experience when we go to the movies.

When watching a film at home, or at a theater using digital projection, this work that so delights many human brains in movie theaters, and hopefully will for a long time--this work is done for you. There's no 24 frames per second bullcrap at home. These images are electronically blended together for you, like processed food. As a result, if a film is not loud or dramatic enough to punch through to the viewer by sheer force, one can find themselves meandering away, easily distracted by a ringing phone, by a light or a noise, by a lover or friend, by a pet, or by one's own thoughts. This might be something most movie viewers have never thought about. Or maybe, if they did, their distractions were merely attributed to the small size of the TV screen, or to some perceived fault of the movie or its makers.

Preserving the exhibition of 35mm is important in many ways. I signed the petition and passionately support this cause.

Hear, hear. Well said, Dennis. In case you're interested, I cited your piece in a blogpost in support of this effort. Thanks.

Post a Comment