Every so often someone wonders out loud or in print (and undoubtedly much more frequently to themselves) about the value of personal experience in writing about films—how far does a good writer go interjecting themselves or their life experience into a review as a point of reference or mode of analyzing what’s happening on screen? My own suspicion is that good film criticism, or at least the kind I’m most interested in reading, can’t

not betray the mind and the personality of the person writing it— using every tool at their disposal to literally guide the reader to

re-view a film from a specific perspective (theirs) is usually a journey worth taking, regardless of the final verdict. This is decidedly not the kind of writing I was first exposed to (and made to cough up myself) when I was studying film in college. I have no bone to pick with academia, but I’ve had to conclude, after 35 years or so, that dry scholastic exegeses and self-consciously overwritten prose about the movies is not the best way for me to enter into a discussion about them. Yet I can think of specific pieces by Pauline Kael, David Edelstein, Stephanie Zacharek, Jim Emerson, Matt Zoller Seitz, Andrew Sarris, Molly Haskell and just about every other critic that I admire that have approached movies with intelligence and style, but also with an eye toward not being ashamed or resistant to how their own life experience, political perspectives, awareness of their own moods and prejudices, can enrich the consideration of the film for the reader. It’s not hard to imagine this being a through- line for all the reading about film that appeals to me, and that includes the people I admire who are writing about film online.

One such person is

Bill Ryan, proprietor of

The Kind of Face You Hate, who consistent writes interesting pieces about what he’s seeing with no regard to trends and prevalent attitudes. Bill’s pieces are primarily his reaction to what he’s seeing, and if that sounds reductive I don’t mean it to. He has an intellect that prevents him from frequently jumping to visceral conclusions without at least wondering why it is he’s feeling that way, a simple requirement for any good critic. But he’s not afraid of his initial reactions either—anyone who followed the discussion the two of us had about

Inglourious Basterds the summer before last will know this to be true. Bill’s taste in films is also happily, unselfconsciously eclectic and hard to pin down, and his enthusiasms can be very convincing. (He is almost entirely responsible for turning this David Mamet resister into someone who can appreciate the likes of

Spartan and

Redbelt and, most astonishingly,

Homicide-- but don’t get me started on that dull puppet show called

House of Games.) So I was very interested in what Bill was going to make of seeing Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 cult hit

House, which has just been released on DVD and Blu-ray. The only thing I knew I could count on from Bill was honesty, no matter what his final assessment, and that’s exactly what I got:

“House is a true cult item, and it's recent DVD release from the good people at Criterion has turned it into one that all the kids are talking about … A plot summary of House is futile, and would be boring... This review may well turn out to be that anyway, but if so at least I'll go about it my own way. The problem is, I do not know what to do with a film like House… Don't be fooled into thinking that House is nothing but an incoherent mess, however. It sort of isn't! In terms of narrative, and logic, and all that stuff, sure, but visually -- which you sort of have to sense is what really matters to Obayashi -- it really is pretty consistent. Theoretically, I suppose that's easy enough to accomplish in a film where anything goes, but you can't watch House and not understand that Obayashi is a director who knows what he wants. Whether or not you want the same thing is an entirely different matter, and as captivatingly absurd as the film can be at times, I found it at least as often to be the kind of movie that I wanted to tell to go fuck itself.”

“House is a true cult item, and it's recent DVD release from the good people at Criterion has turned it into one that all the kids are talking about … A plot summary of House is futile, and would be boring... This review may well turn out to be that anyway, but if so at least I'll go about it my own way. The problem is, I do not know what to do with a film like House… Don't be fooled into thinking that House is nothing but an incoherent mess, however. It sort of isn't! In terms of narrative, and logic, and all that stuff, sure, but visually -- which you sort of have to sense is what really matters to Obayashi -- it really is pretty consistent. Theoretically, I suppose that's easy enough to accomplish in a film where anything goes, but you can't watch House and not understand that Obayashi is a director who knows what he wants. Whether or not you want the same thing is an entirely different matter, and as captivatingly absurd as the film can be at times, I found it at least as often to be the kind of movie that I wanted to tell to go fuck itself.”The preceding paragraph, it should be understood, was assembled from a few sentences peppered throughout the first couple of paragraphs of Bill’s piece. There’s a lot of consideration of what’s happening visually in Obayashi’s film that

you can read for yourself, and I hope you do, because futile or not, Bill has a good time recounting some of the strange things that happen in

House on his way to describing his own ambivalence about the film. And as the above excerpt indicates, I definitely think Bill is ambivalent about the movie. Frankly, I wouldn’t trust anyone who didn’t have the capacity to contain a lot of contradictory emotions and reactions to a movie like this. And I don’t think that ambivalence, especially in this case, is necessarily cleaved to a connotation of negativity. In fact, it may be an indication of a desire for further inquiry or experience, or at least a certain joy in the recounting of one’s own warring impulses while watching a film, impulses which certainly provide the structure of Bill’s piece.

*******************************************************

But one thing I was led to think about while reading Bill’s post was the nature of seeing something like

House, especially for the first time, in relative isolation. Peter Nellhaus was thinking along the same lines and started out a lively (if uncharacteristically, for Bill’s place, brief) comment thread wondering about the difference between seeing

House in a packed auditorium and watching the DVD at home, presumably alone or at least with minimal distraction. I can’t imagine that seeing the movie with an audience would have led Bill to paper over or simply not have some of the reactions he had to seeing

House on DVD. But I do think that the energy of seeing it communally with an appreciative audience would have lent a different energy to the experience. Would he have wanted to tell the film to go fuck itself

as much? Or maybe

more? (I can recall certain experiences seeing

The Rocky Horror Picture Show that made me seriously consider arson.) Who knows? It’s not a question that can necessarily even be answered by a second screening in a theater—that first experience is what it is. But I think there’s a lot to be said for that theatrical experience, whenever it might come, and I’d be very curious to read Bill on the movie after such a screening. My own first experience with

House was on a big screen with an audience, which as any theatrical frequenter of cult movies knows, can be fraught with its own perils. Seeing the image and hearing the sound amplified to this scale is

always a good thing, but a crowd’s behavior can color the experience in both positive and negative ways. The group of 200 or so viewers I saw it with was primed for an odd experience, to be sure, and eventually (maybe due to the late hour—it was a midnight screening) they settled down. But at first the audience was as much about itself—overeager laughter, loud wisecracks and other semi-boorish noise intended to clue others in that they “get” the movie—as it was about the cacophonic insanity of Obayashi’s imagery.

A little of this kind of nonsense can go a long way toward spoiling a movie (at least for me), and sometimes the gulf between what an audience is experiencing in the same theater can be too much. When I saw

Antichrist, a couple of months after its original, brief theatrical run had ended, the auditorium was pocketed with small groups of people determined to make their own dissatisfied reaction to the film known. The jokester element reacted as if they were watching Andy Warhol’s

Bad, unconcerned with how callous and rude their unmodulated braying came across in this context. Everybody’s got a story like this. It’s the potential trade-off you make, especially in this age of cell phones and PDAs and iPods and video games—the possibility that someone in a crowd will make the effort, consciously or unconsciously, to fuck up the communal bliss of sitting in the dark at the mercy of any movie, whether it’s

House (1977), or

House (1986), or

House (2008), or even

House! (2000).

*******************************************************

Even film festivals, where you’d think common courtesy might be in more generous supply, are not immune to thoughtless distractions. The guy sitting next to me at the AFI Fest screening of Werner Herzog’s

Cave of Forgotten Dreams was clearly being overwhelmed by the movie’s majestic, though at times claustrophobic imagery. Several times, while the mysterious images captured by Herzog’s 3D camera were ostensibly seducing the audience, this guy, someone supposedly interested enough in film to take the trouble to seek this movie out at a festival, opened up his cell phone several times to check his messages or perform some other

very important function. Of course the bright light emanating from his phone screen was plenty enough to break the spell being cast by the film, so after about the third instance of this inconsiderate boob’s phone jockeying I decided to take a page from someone I read about whose patience had reached its limit with his own neighboring agent of distraction. I began noticeably turning my attention away from the screen and toward his phone. This happened twice, and neither time did I actually

say anything—I just suddenly turned my head and shifted my gaze from the big screen to his tiny one, where there

must be something more fascinating going on. Right? Well, after the second time I did this (a little more obviously than the first) Mr. Verizon clapped his phone shut and it stayed that way for the rest of the film. But the fact that it would have occurred even once leads me to some pretty depressing conclusions about the way we seem to have lost touch with common sense courtesies when it comes to interacting with others in public situations, and it’s not unreasonable to presume that much of this ineptitude can be traced to how much more easy it is in the 21st century to experience films and other arts and entertainments in a solitary fashion, where it doesn’t matter if you burp or fart or snore or check your phone every five minutes, where you can rewind to catch a piece of dialogue you might have missed whilst snoring, or punch up the display function to see how much more this boring art snoozer you feel obligated to endure has left to go before the merciful end. Then again, there’s always the possibility that home theater convenience is less to blame than we’re willing to concede. Maybe these people are just self-centered assholes.

Entirely separated from the glow of nearby iPhones, Herzog’ movie has much to recommend it. The irascible, gloomily funny director narrates his own admittance into a very exclusive club—the perfectly preserved 1,300-square-foot Chauvet cave complex discovered by explorers in 1994 onto which humans had not laid eyes for some 35,000 years. The fascination lies in the paintings drawn on the walls of this cave, the contours and recessions and surface textures of which were used by these primitive artists to tell stories and effective “animate” the figures of horses and bears and other elements of early life during mankind being depicted. Despite his own reservations regarding the limitations of 3D (which Herzog elucidated with conviction after the screening during a brief Q&A), his use of the once-again-popular technology in this context turns out to be a master stroke. Seen flat, the paintings retain their historical and geological fascination, but it seems possible that they would not survive the ecstatic scrutiny to which Herzog’s camera (manned by masterful cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger, working with video cameras he and his crew had to assemble once inside the cave) subjects them without the illusion of depth. In 3D, however, Herzog is able to tease out every ounce of fascination with the paintings—the contours which the artists used to simulate motion and movement pop out at us subtly, as they would if we were seeing them in the cave ourselves. The 3D, combined with the geological composition of the cave walls themselves, sparkling and glistening with untold geologic treasures and compounds, completes the illusion for us—these paintings often do seem alive. The tactile experience is enhanced by the play of light across the cave surfaces, used to illuminate the images for us, of course, but also inadvertently simulating the flickering torchlight by which the artists themselves created the paintings and experienced them as depictions designed to bestow life onto the images. There are even drawings of animals with eight or more legs rendered in a kind of blur, which Herzog, in that omniscient narrator’s voice we’ve all come to love, speculates were created to imply movement, much like in a series of drawings designed for an animated film, a quality Herzog dubs “proto-cinematic.”

The 3D technology works surprisingly well considering the relatively low-tech and very quick shoot (six days), though there are shots which provide too much tension for the eye and were difficult (at least for this relative experienced 3D watcher) to comfortably, naturally process. But those moments are natural by-products of Herzog’s priorities. It will be no surprise that 3D imagery is not the end itself for him but instead a means one; his use of the trendy medium is refreshingly casual. In fact, in the Q&A afterward Herzog himself made a convincing case

against 3D. His argument is that 3D limits what can be gleaned from the imagery, by means of suggestion or other artistic strategies, due to the fact that it is designed to specifically guide your eye to seeing the image in a certain specific and (for him) limited way. For Herzog, the theoretically 3D guide cannot yield up anything more than what is shown—the screen becomes, ironically, shallow and impenetrable, sealed off from interpretation. But Herzog’s career has often embodied a gulf between what’s on screen and the director’s expressions of intent and theory, and that is most certainly the case here. Herzog discounts the very aspects of 3D that accentuate the most amazing elements of his subject matter here. With 3D we can see the recreation of the illusion of these cave drawings taking on life, which then leads to our own flights of imagination regarding how the images were created, how the effects were achieved, the physical experience of seeing the paintings in the cave and, of course what others secrets the cave might hold. Surely he’s correct that 3D instructs the eye to process the image in a certain way. But in the hands of directors like Herzog, or Joe Dante, or

Despicable Me’s Pierre Coffin and Chris Renaud , the 3D image isn’t a limitation but an invitation to experience the heightened reality of a physical and emotional response to the images being choreographed and recorded in 3D. It’s precisely the brilliantly intuitive use to which Herzog puts the process, alongside the passion of inquiry and empathy and interpretation that the director typically brings to his documentary work, that elevates

Cave of Forgotten Dreams into another dimension.

************************************************************

The audience seemed enthralled by Herzog’s film (with one obvious exception, of course), and it was a real treat to have him there in person, doubly so because the crowd (over 1,000 people filled the big auditorium) was atypically large—just ask anyone who has paid to see a Werner Herzog movie on a Saturday night anytime over the past 20 years--

Grizzly Man included, I would guess. And though the director, who flew in Florida where he had been filming that very morning just for the Wednesday evening screening, was clearly exhausted, he reveled in the audience’s enthusiasm and took several of their questions with articulate, good humor. The irascible

Burden of Dreams-variety Herzog did make a brief appearance, however, much to the delight of at least the folks in my general vicinity. Near the end of the film Herzog’s crew makes their way to a strange biosphere located on a river just downstream from France’s largest nuclear power plant. Inside he discovers a crocodile breeding farm, from which have emerged two albino crocodiles. Herzog’s 3D camera captures some fascinating, intimate and unsettling shots of these reptiles swimming and being reflected by the water’s surface. The appearance of these ghostly creatures also gives Herzog the opportunity to go metaphor hunting, and he bags a juicy one, speculating in that clipped German accent about these creatures, mutated from exposure to nearby radioactivity, and how they see the world. Do they see it with the same kind of detachment that we gaze upon those cave paintings? How would the

crocodiles see those paintings? It’s precisely these kinds of lunatic flights that make Herzog movies Herzog movies—we even got an iguana’s eye-view of the world in last year’s

Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

But during the Q&A Herzog, that Teutonic rascal, revealed with some relish that the albino crocodiles were actually alligators and that, despite the information he propagated in the movie, were not born in the biosphere but instead imported by its owners from Louisiana, and that he merely appropriated their image as a jumping-off point for the strangely poetic, left-field conclusion to his documentary. As Herzog said, it was a factual manipulation employed to get at a different, deeper perception. The audience then laughed and the director suddenly looked somewhat perturbed (which made me wonder how much he bristled during the occasional laughter, usually directed at the text and timbre of his narration, heard during the film itself). When he repeated his assertion about the use of his artistic license, somebody in the audience piped up, “The lie that tells the truth!” Herzog stiffened, and over the lingering laughter he turned toward the voice and said, testily, “What did you say?” The commenter shouted out his observation again: “The lie that tells the truth!” Herzog's face, friendly up to that point, morphed into one of his patented scowls. “I am

not lying!” he flung back, and proceeded to give a mini-lecture to the offending audience member, and anyone else who might have had the same thought, about the moral imperatives behind reaching for a kind of ecstatic poetry that transcends the limitations of the facts, or at least allows for the creative scrambling of them. It was a giddy and somewhat unexpected way to end an evening spent with Herzog’s transcendent, somber and awestruck documentary. I only wish that he’d noticed that jerk sitting next to me all aglow and stomped his way down to our seats mid-film to give him a good Germanic what-for as well.

*************************************************************

The film immediately following on this penultimate evening of the AFI Fest was the Los Angeles premiere of Jean-Luc Godard’s latest,

Film Socialisme, which premiered to much scandal and tumult at Cannes earlier this year. It would be the first time I’d have seen a new Godard movie theatrically since (I think)

Detective back in 1985, and the irony of the movie—any Godard movie—making an appearance at the upstairs Chinese complex, located in the Hollywood and Highland outdoor mall complex, hopefully wasn’t lost on everyone. This is the place that, as my friend Matthew David Wilder observed in a Facebook note posted the morning after the screening, features a central courtyard modeled after the gargantuan sets used in D.W. Griffith’s

Intolerance, located as it is mere yards from the Knickerbocker Hotel where it is said Griffith died. Adding to the odd vibe was the fact that here was a late-period Godard film, one made long after the director had sloughed off any pretense to narrative in favor of the audio-visual collage style that would mark his final separation from the low cinema he once so rigorously referenced, playing to probably the largest audience assembled for any Godard film in America since the days of

Contempt. (The main auditorium of the upstairs Chinese complex where

Film Socialisme screened has over 1,000 seats.) So it was with not a small amount of expectation and anticipation that my friend and I sat down for what was surely going to be a unique, characteristically “difficult” experience. In fact, the AFI staffer who introduced the film was quite deliberate in letting anyone who may have just wandered in because the tickets were free just what they were in for, right down to describing Godard’s use of “Navajo subtitles,” a form of broken English meant to parody the rudimentary fashion by which even non-English speakers experience English as a “common language,” subtitles which would, as Wilder describes them, “further complicate (Godard’s) blizzard of Babel without once plainly elucidating the dialogue.” In other words, here was a director not satisfied with sending his film off to be subtitled by some anonymous post-production house, come what may of the translation. Instead, the subtitles were, to my understanding, intended to play a key role in how Godard designed his film to be perceived, especially by audiences unfamiliar with the French, German and other languages used in the film. I was looking forward to seeing how this conscious use of translation would jibe or contrast with the images (I couldn’t look forward to making the same kind of distinction with the language, as English is the only one I speak and understand.) My friend, who claims about 75% fluency with French, might have an even richer experience.

Imagine our surprise then when, after about five minutes of film sans subtitles, the lights went up and another AFI staffer had the unpleasant task of reminding the audience that what we were seeing was an entirely digital presentation and that, through some unbelievable oversight, the film arrived to AFI downloaded

without the subtitles. Since it’s seems a reach to imagine that subtitles would have to be downloaded separately for theatrical exhibitions such as these, I’m not sure I buy the initial explanation. Why would they not be burned onto the image in the standard fashion? But whether or not the subtitles were indeed missing or just inaccessible because of operator unfamiliarity with the system for retrieving them, it was clear that we are all invited to stay and watch the film

sans subtitles. According to Wilder, whose own French, he admits, could be better, the entirety of the audience, minus a few walkouts, stayed, even though it could be reasonably assumed that most of those who stayed were even less conversant in the film’s primary language than Wilder, who wrote of the unintended language barrier, “Afterwards, everyone explained their incomprehension of the movie by saying, ‘Well, I don't speak French!’” (Could it be that the secret to

enjoying Godard's late-period films is to shut off the subtitles?)

Wilder ended up writing some interesting notes on the film regardless, but it’s time to admit that my friend and I were among the few who didn’t mind being seen walking out of a Godard film that night. Even a French speaker, after all, would have had to contend with the myriad different languages represented in Godard’s audio text, so it would seem subtitles would have been if not a necessity, then at least an aid (Godard’s own subversion of understanding aside) in interpreting the information on screen. But to a monolingual such as myself, I could not be satisfied with looking at 91 minutes of Godard’s admittedly astonishing digital imagery. And given that the subtitles were reportedly designed by Godard to be an integral part of the experience for English-speaking viewers, the AFI, through this screw-up which could have at least been detected before the actual screening, facilitated showing a version of

Film Socialisme that was missing an element deemed crucial by the none-too-permissive director himself. Congratulations to those who were there to be seen attending a Godard film—duly noted. My embarrassment at walking out, however, pales next to how pretentious I would have felt had I stayed. Leaving seemed far more preferable to being seen filing out by all the rest of the hardy, unaffected crowd, pretending the movie meant anything more to me than a series of compelling pictures out of context, a Pink Floyd Laserium show for the film snob hiding within. There are rumors, as there always are, of a possible theatrical release for this new Godard film. If it happens, I’ll be there. I just hope they send along something to read as well.

*************************************************************

There are fewer experiences in movies more pleasurable than connecting with an audience, particular with horror films and comedies, where vocal expression of the audience’s reaction is frequently part of what we appreciate about them—the raucous laughter, the collective scream. Seeing

House minus that sense of discovering something along with 200 other people that gives no clue as what will happen next, or as Bill says the sense that anything could happen, and will, is a key to the whole experience, I think. Without it, the experience becomes slightly detached. Appreciation is still possible, and so is emotional involvement; immersion in the film’s world is tougher. Over the past year I had occasion to see two of my favorite movies-- W.C. Fields’

Never Give a Sucker and Even Break and Howard Hawks’

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, on DVD and then in theaters. I had loved both of them for a long time and remembered them both as being hilarious, but on DVD, without the infectious participation of a crowd surrounding me with laughter, prompting me to respond in kind to what

they thought was funny (if and when those two perceptions should ever differ), both were much more calm, measured affairs. I smiled a lot, and I chuckled a lot, but belly laughs were largely absent. Luckily for me (and everyone who managed to attend), both movies recently screened at the New Beverly Cinema, and no more impressive comparison need ever be made. I brought my entire family, including my in-laws, to see W.C. Fields, and it was thrilling to hear a full house erupt into spasms of laughter at the Great Man’s every utterance.

But seeing

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was as close to a genuine revelation as I’ve had at the movies in years. The New Beverly screened a brand-new, never-before-seen 35mm Technicolor print that was stunningly beautiful—each widening of Monroe’s eyes was as clear and striking as a sunrise seen through cut diamond, and every element of the design of the movie, from the wild and wonderful costumes to the ornate sets lit up to heaven by cinematographer Harry J. Wild, seemed to be beamed in with laser-sharp intensity. Though I’ve long loved it, the movie never seemed more than a funny, fanciful trifle before. But as the first strains “Just Two Little Girls from Little Rock” rang out over the New Beverly’s sound system last Saturday night I felt something akin to a physical sensation of my own senses being heightened, and not just slightly. I was overwhelmed by the information I was receiving, a sort of excitement I have rarely felt watching any movie. As the film proceeded, I felt like Max Renn in

Videodrome, my neural receptors having been opened up to a new experience that was there lying latent under the surface of the movie since 1953 just waiting to be unleashed. What was always just a cute comedy and a charming musical before was certainly still both of those things, but suddenly, in high relief, I could also see an incredibly sharp reversal of sexual roles and morality in which Marilyn and Jane reveled in playing by the man’s rules and having their surface-crass intentions revealed as the moral and social high ground in romantic/sexual relationships. This film was produced in 1953, when most women other than stars like Monroe and Russell were still living out lives of subservience to men, on the professional as well as domestic circuit. But why should this have been so surprising, coming as it did from the director of

Bringing Up Baby, Only Angels Have Wings and

His Girl Friday, a director who has never shied away from depicting women as able to stand ground with men on their own terms as well as that of their male colleagues and rivals? Last Saturday night

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes gained in stature for me, morphing from a favorite to a masterpiece, and it took seeing it under the most perfect of conditions, in a favorite place, projected from a beautiful new print, and in the presence of a room full of people who were open to it in every way, for that to happen. I’ll still cherish my DVD, but I couldn’t feel any more lucky or privileged to have had the chance to see it this way.

*******************************************************

Wrapping up a theme, here’s one last great audience moment-- the Cinefamily’s wild and woolly Halloween offering,

The 100 Most Outrageous Kills , is poised for a repeat this coming Saturday, November 13, at 10:00 p.m. Let the Cinefamily ‘splain itself, in their own words:

“From the golden age of gore-mastery to the innovative new technologies of modern effects wizards, cinema is littered with the bodies of the awesomely dispatched -- and cold-blooded murder, in the hands of innovative filmmakers who present it in ways we’ve never seen before, can be a heavenly fine art. Tonight, in a show originated at Austin, Texas’s Alamo Drafthouse, we’ll be celebrating the absolute finest in on-screen annihilation with a non-stop nightmare of intestine-ripping, head-bursting, unrepentant baby-eating and other crimson-soaked savagery! This night is intended for the most severe and iron-stomached bloodhounds around, and we accept absolutely no responsibility for lost lunches. Wimps and weekend horrormeisters, leave the hall; if you can’t stand the meat, stay out of the kitchen. See all you death beasts in the murder pit!!!!”*************************************************

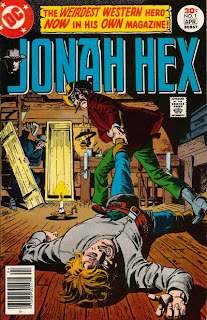

“Jonah Hex!” he shouts with twisted delight upon encountering our hero, “I’d recognize that undercooked pie hole anywhere!” The buzz is translated to the audience— Fassbender is, as always, magnetic. He’s the thinking person’s Sam Worthington, and as such it'll be no shock that he hasn't yet nailed the role that would make him a global star. (He and we might be better off if he ultimately doesn't.) But the movie rests on the weary but wide shoulders of Josh Brolin as the disfigured, disconsolate but ever-motivated Hex, a character drawn from a series of mid-70s DC comics whose revival in graphic novel form presaged this movie adaptation. On the page Hex has a personage much more resonant of hell-spawned demons than the more human carriage of guilt and fury weighing down Brolin’s Hex as he travels the prairies and mountains, first as a bounty hunter, then as a supernaturally-aided avenger. But even without the white-hot brimstone packaging, the temptation might have been to play Hex exclusively for his grim purity, a single-minded vision of hate-filled eyes burning for revenge, Clint Eastwood by way of Coffin Joe. Brolin, fortunately, allows for some humor—he has a way with a slightly upturned eyebrow when measuring his enemies that would make any good comic envious. And he does well with the obligatory dry one-liners— “What happened to your face?” taunts one of Turnbull’s goons, to which Hex responds with a tomahawk to the neck and an elegantly tossed-off “I’m all out of wise-ass answers,” a clue to Hex’s weariness as well as a nifty rejoinder to a couple decades worth of witty (and more often wilted) movie comeback lines.

“Jonah Hex!” he shouts with twisted delight upon encountering our hero, “I’d recognize that undercooked pie hole anywhere!” The buzz is translated to the audience— Fassbender is, as always, magnetic. He’s the thinking person’s Sam Worthington, and as such it'll be no shock that he hasn't yet nailed the role that would make him a global star. (He and we might be better off if he ultimately doesn't.) But the movie rests on the weary but wide shoulders of Josh Brolin as the disfigured, disconsolate but ever-motivated Hex, a character drawn from a series of mid-70s DC comics whose revival in graphic novel form presaged this movie adaptation. On the page Hex has a personage much more resonant of hell-spawned demons than the more human carriage of guilt and fury weighing down Brolin’s Hex as he travels the prairies and mountains, first as a bounty hunter, then as a supernaturally-aided avenger. But even without the white-hot brimstone packaging, the temptation might have been to play Hex exclusively for his grim purity, a single-minded vision of hate-filled eyes burning for revenge, Clint Eastwood by way of Coffin Joe. Brolin, fortunately, allows for some humor—he has a way with a slightly upturned eyebrow when measuring his enemies that would make any good comic envious. And he does well with the obligatory dry one-liners— “What happened to your face?” taunts one of Turnbull’s goons, to which Hex responds with a tomahawk to the neck and an elegantly tossed-off “I’m all out of wise-ass answers,” a clue to Hex’s weariness as well as a nifty rejoinder to a couple decades worth of witty (and more often wilted) movie comeback lines.

Admittedly, Jonah Hex’s aspirations exceed its reach—tonally, the movie never strikes a proper balance between its western roots, the overtly supernatural elements that occasionally lead it into blackly humorous Tales from the Crypt territory, and its own desires to fulfill the visual ambitions of the stock Hollywood blockbuster. Turnbull hopes to take his own personal extension of the War Between the States to a national level with the help of a high-tech weapon which fires little gold cannonballs that deliver much pictorially impressive destruction. But as Jonah inches closer to foiling Turnbull’s plot, the movie inches closer to a more 21st-century Hollywood conventional conclusion, an episode of Mission: Impossible on horseback, or worse yet, an unfortunate reminder of another TV western adaptation which this leaner, meaner movie thankfully far outstrips. And certainly I would have appreciated the casting of someone other than the plasticine Megan Fox as Hex’s romantic interest. This Flavor of the Moment’s heavy-lidded beauty and flat-line vocal expressions remind me of nothing so much as a blow-up doll on opiates; she hasn’t the spark to make me believe in her character’s feisty survival instincts. (Think what an equally beautiful but far more interesting actress like Mila Kunis or Maggie Q could have brought to this role. Fox, on the other hand, only makes me think she’d like nothing more than to blow off this movie stuff, curl up in her trailer and go to sleep.)

Admittedly, Jonah Hex’s aspirations exceed its reach—tonally, the movie never strikes a proper balance between its western roots, the overtly supernatural elements that occasionally lead it into blackly humorous Tales from the Crypt territory, and its own desires to fulfill the visual ambitions of the stock Hollywood blockbuster. Turnbull hopes to take his own personal extension of the War Between the States to a national level with the help of a high-tech weapon which fires little gold cannonballs that deliver much pictorially impressive destruction. But as Jonah inches closer to foiling Turnbull’s plot, the movie inches closer to a more 21st-century Hollywood conventional conclusion, an episode of Mission: Impossible on horseback, or worse yet, an unfortunate reminder of another TV western adaptation which this leaner, meaner movie thankfully far outstrips. And certainly I would have appreciated the casting of someone other than the plasticine Megan Fox as Hex’s romantic interest. This Flavor of the Moment’s heavy-lidded beauty and flat-line vocal expressions remind me of nothing so much as a blow-up doll on opiates; she hasn’t the spark to make me believe in her character’s feisty survival instincts. (Think what an equally beautiful but far more interesting actress like Mila Kunis or Maggie Q could have brought to this role. Fox, on the other hand, only makes me think she’d like nothing more than to blow off this movie stuff, curl up in her trailer and go to sleep.)  I was an avid reader of the comic’s initial incarnation in 1977, but stopped reading well before its cancellation in 1985, yet I only caught the movie on DVD a few nights ago after having missed it during its short theatrical run. And I was more than a little surprised by the fact that I enjoyed Jonah Hex quite a lot. Even so, I feel like I was holding my breath for at least the first half in dread of stumbling upon the moment when the movie would turn into the stinker I’d been led to believe it was from the multitude of dismissive reviews rained upon it this past June. Strangely, it never came. After the movie ended, it was no surprise to check out the roster of writers who had issues with the movie, some more intelligently expressed than others, to be sure. And I had remembered than Armond White liked it. But White’s prose reads like the words of someone desperate to justify his enjoyment of the movie by avoiding addressing it with anything like its own tone. When White writes, “Jonah’s post-Civil War adventure parallels contemporary malaise. N&T adapt the… comic book to fit their timely sense of disquiet and cultural confusion—that post 9/11 dread that Bruce Springsteen aptly described as ‘a fairy tale so tragic,’” well, let’s just say we differ as to why we liked Jonah Hex.

I was an avid reader of the comic’s initial incarnation in 1977, but stopped reading well before its cancellation in 1985, yet I only caught the movie on DVD a few nights ago after having missed it during its short theatrical run. And I was more than a little surprised by the fact that I enjoyed Jonah Hex quite a lot. Even so, I feel like I was holding my breath for at least the first half in dread of stumbling upon the moment when the movie would turn into the stinker I’d been led to believe it was from the multitude of dismissive reviews rained upon it this past June. Strangely, it never came. After the movie ended, it was no surprise to check out the roster of writers who had issues with the movie, some more intelligently expressed than others, to be sure. And I had remembered than Armond White liked it. But White’s prose reads like the words of someone desperate to justify his enjoyment of the movie by avoiding addressing it with anything like its own tone. When White writes, “Jonah’s post-Civil War adventure parallels contemporary malaise. N&T adapt the… comic book to fit their timely sense of disquiet and cultural confusion—that post 9/11 dread that Bruce Springsteen aptly described as ‘a fairy tale so tragic,’” well, let’s just say we differ as to why we liked Jonah Hex. Well, add Zacharek’s keen review of Jonah Hex, published last June on Movieline, to that list. Zacharek starts off with a line that might lead you to think you’re in for one of those “It’s so bad it’s good” pieces: “There’s something to be said for low expectations, especially when it comes to summer movies.” Let the nudge-nudge-wink-wink condescension begin, right? Well, no. This critic then proceeds to neatly sum up precisely why the movie worked for her, in language that suggests she enjoys engaging with it on its own lowdown terms. It has something to do with Josh Brolin playing Hex “with a wink and a snarl” and “a relatively restrained John Malkovich — for once he cuts the scenery into bite-size morsels before chewing it.” But after elaborating where the movie also doesn’t work for her (including a train robbery sequence that, despite a horrifically explosion conclusion, fizzles for momentum’s sake), she settles on praising director Hayward for the “downright leisurely” way he approaches the film’s visual strategy. In the essay's highlight, Zacharek writes:

Well, add Zacharek’s keen review of Jonah Hex, published last June on Movieline, to that list. Zacharek starts off with a line that might lead you to think you’re in for one of those “It’s so bad it’s good” pieces: “There’s something to be said for low expectations, especially when it comes to summer movies.” Let the nudge-nudge-wink-wink condescension begin, right? Well, no. This critic then proceeds to neatly sum up precisely why the movie worked for her, in language that suggests she enjoys engaging with it on its own lowdown terms. It has something to do with Josh Brolin playing Hex “with a wink and a snarl” and “a relatively restrained John Malkovich — for once he cuts the scenery into bite-size morsels before chewing it.” But after elaborating where the movie also doesn’t work for her (including a train robbery sequence that, despite a horrifically explosion conclusion, fizzles for momentum’s sake), she settles on praising director Hayward for the “downright leisurely” way he approaches the film’s visual strategy. In the essay's highlight, Zacharek writes: