SEEING AND WRITING (AND SEWING): QUALITY TIME WITH STEPHANIE ZACHAREK

If you’re familiar with the little “On the Marquee” shortcut on the sidebar of this blog, you probably know that throughout the year I only write about 5% of the movies I actually see. Some of that is due to how much time I can actually devote to writing, and some of it is due to sheer laziness. (I usually try to make up for these shortcomings in my year-end posts.) But whether I write about a movie or not, I try to find interesting pieces—reviews, essays, whatnot—about each title to make available at a click, whether or not those pieces represent my own point of view. (The four-star system, a bit of shorthand from which I just don’t seem to be able to fully divorce myself, takes care of that in a pinch when all else fails. Thanks, Mr. Maltin.) And one of the critics I seem to turn to most frequently in “On the Marquee” is Salon magazine’s senior film critic, Stephanie Zacharek, whose work I have admired for years, even on those occasions when we disagree, as representative of the kind of writing about movies that, by design and insistence of deadline, must understand the movie in its moment, but is also cognizant and respectful of the richness of film history, which is frequently accessed and encompassed in the work she does. She’s smart, funny, and she loves The Lady Eve. What else do you need to know? Well, if that question is more than a rhetorical one, you’ve arrived at the right post. Recently Stephanie, who through her warm and friendly demeanor has fast become one of my favorite people, agreed to sit down with me for a webcam conversation via Skype (She’s in Brooklyn, I’m in Glendale) about as many things as we could pack into a hour—growing up with the movies, meeting Pauline Kael, movies she loves to stand up for, film criticism in the age of Internet interactivity, and much, much more. At some point I forgot I was supposed to be conducting an interview and, for me, it became more of a relaxed conversation. I sincerely hope that our time, transcribed here, is as much fun for you to read as it was during the moment for the two of us. She has a standing invitation to return to these pages anytime. We start, as most stories do, at some sort of beginning. (Cue 20th Century Fox theme music.)

If you’re familiar with the little “On the Marquee” shortcut on the sidebar of this blog, you probably know that throughout the year I only write about 5% of the movies I actually see. Some of that is due to how much time I can actually devote to writing, and some of it is due to sheer laziness. (I usually try to make up for these shortcomings in my year-end posts.) But whether I write about a movie or not, I try to find interesting pieces—reviews, essays, whatnot—about each title to make available at a click, whether or not those pieces represent my own point of view. (The four-star system, a bit of shorthand from which I just don’t seem to be able to fully divorce myself, takes care of that in a pinch when all else fails. Thanks, Mr. Maltin.) And one of the critics I seem to turn to most frequently in “On the Marquee” is Salon magazine’s senior film critic, Stephanie Zacharek, whose work I have admired for years, even on those occasions when we disagree, as representative of the kind of writing about movies that, by design and insistence of deadline, must understand the movie in its moment, but is also cognizant and respectful of the richness of film history, which is frequently accessed and encompassed in the work she does. She’s smart, funny, and she loves The Lady Eve. What else do you need to know? Well, if that question is more than a rhetorical one, you’ve arrived at the right post. Recently Stephanie, who through her warm and friendly demeanor has fast become one of my favorite people, agreed to sit down with me for a webcam conversation via Skype (She’s in Brooklyn, I’m in Glendale) about as many things as we could pack into a hour—growing up with the movies, meeting Pauline Kael, movies she loves to stand up for, film criticism in the age of Internet interactivity, and much, much more. At some point I forgot I was supposed to be conducting an interview and, for me, it became more of a relaxed conversation. I sincerely hope that our time, transcribed here, is as much fun for you to read as it was during the moment for the two of us. She has a standing invitation to return to these pages anytime. We start, as most stories do, at some sort of beginning. (Cue 20th Century Fox theme music.)**************************************************

Dennis Cozzalio: When did the movies first become important for you?

Dennis Cozzalio: When did the movies first become important for you?Stephanie Zacharek: Well, I was very little. I guess the first movies I really remember watching—I would watch the Creature Feature on Saturday afternoon, stuff like that, and I would watch Monday Night at the Movies on one of the TV networks, whatever was on there. I had an older sister who was really into black-and-white classic movies—Fred Astaire and that kind of thing. And in those days—this was before videos and VCRs, ashamed and embarrassed to say—you had to stay up really late to see anything like this. Luckily, I had very permissive parents who allowed me to stay up, but who really didn’t know what I was doing half the time! (Laughing) So I’d stay up late with my sister, and sometimes by myself, or with my mom, even, and would watch these old movies.

And then when I got a little bit older—PBS used to do these series of foreign films, and when I was about 12 years old that’s when I saw Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, Jules and Jim-- And that one really blew my mind—“People actually live like this?!” And for a long time I watched whatever PBS offered up. It’s funny to think that a lot of times people say, “Oh, my kids won’t watch anything with subtitles.” And as a kid myself I don’t even remember making the distinction between a movie with subtitles and one without them. But that was probably the first time I ever became conscious of them as, I don’t want to say “more than entertainment,” but I would look at these movies and realize, Okay, this is a cut above the average made-for-TV movie you’d see on the ABC Movie of the Week. The first movie I ever saw in a theater was Thomasina, a Walt Disney movie about a cat with three lives or something like that who ends up using her three lives. Of course I loved it and managed to get them to take me to see it again. But it wasn’t like I came from a big movie-going family or anything like that.

DC: Did you grow up in a small town?

SZ: I grew up in Syracuse, upstate. So, no repertory house, nothing like that. I’m kind of envious of people who grew up in New York or San Francisco or Boston who had access to all this stuff, because that was definitely not the case with me. I was out in the boondocks.

DC: Me too. I suspect my parents looked at movies in much the same way yours did. My parents weren’t overly interested in them either, so it’s always been a source of curiosity for me to try and trace back and figure out where my interest in the movies came from.

SZ: Yeah, it’s weird, isn’t it? I know Charlie, my husband (film critic Charles Taylor), his dad was very cool and took him to see The Godfather and things like that when Charlie was far too young to see them on his own, which is great. And I remember I went to see Saturday Night Fever with my mother because she had a crush on John Travolta. But otherwise, I really don’t know where it comes from. You find them on your own, and they stick.

DC: I remember having to work very hard to talk my mother into taking me to see Dirty Harry at a drive-in when I was 11.

(SZ laughs)

DC: But that tactic backfired on me several times. I fooled my parents into taking me to see Deliverance--

SZ: Oh, my God.

DC: “Look, Dad, they’re carrying a canoe. It’s a nature movie! This’ll be fun!” I even knew what was coming, and so I ended up sitting between them as the movie is starting and then I realize, “Oh, no. What have I done?” And they weren’t too happy with me afterward. (Both laugh) Yeah, I saw the movie, but at what price?!

SZ: The other thing that was key for me was, my mother was a secretary for Syracuse University, and they would have The New Yorker in the waiting room of the administration building. I was about 12, and she came home with big stacks of them, and I would go through them and read the cartoons, and I’d look at some of the articles but just end up thinking, this is boring! But then I started flipping to the back and I realized that they had movie reviews that were written by Pauline Kael. I knew her name because my mom used to watch The Dick Cavett Show, and occasionally when I would watch with her Pauline would be a guest, so I knew of her from there. But I started reading these reviews and I immediately loved them because I felt she was obviously this incredible writer and intellectual, I never felt like she was writing above my head. What she was doing seemed very accessible and very vivid to me. And she was writing about movies, most of which I hadn’t seen. Most of them I would not see for 10 or 20 years. But she opened up a world, in a way. Reading her made me feel like I had all this stuff waiting for me. At some point when I was older and autonomous, I could go and see this stuff for myself. That was really important to me. But that was a reading experience, not a film-watching experience, and it kind of reinforced some of these other interests in my life that were simmering.

DC: What did Pauline Kael mean to your development as a writer? Did you ever meet her?

SZ: Yeah, I did meet her, and I would say she was a friend. I knew her for the last 10 years of her life. I met her in 1990 through my husband, Charlie. I remember him talking about her and saying, “Would you like to meet her?” And of course I said, “No!” (Laughs) He kept saying, “You’ll love her, she’ll love you.” So eventually we drove out to Great Barrington to see her one day—we were living in Boston at the time—and the first thing I remember—She was a very tiny woman, and by the time I met her she was quite a bit older, so she’d probably shrunk even a little bit more. So we go to the door, and here’s this very small person peering at us from behind the screen. At the time my hair was very long, halfway down my back, kinda wild, and she said, “Oh, you have Annette O'Toole's hair!” (Laughing). That immediately put me at ease.

DC: The Pauline Kael ice-breaker.

SZ: Yeah! I was nervous, but I wasn’t really intimidated by her in that way that a lot of people talk about. After that we would see her occasionally or talk on the phone. It was a little weird meeting and getting to know this person you had been reading for years and not just respected, but sort of revered. And it was the first time in my life where I had this instance of getting to know someone as a person as well as a writer or an artist. She was very important to me, and in the time that I knew her— (Pauses) I have to say I’ve become very protective of her legacy. There were a lot of people who were friends of hers at one time, and some of them waited until after she died-- and some didn’t-- to start tearing her down. Of course, one thing that people have often said about her is, “She only liked male critics. She didn’t want to have anything to do with women.” Well, there weren’t that many women film critics, so I don’t know if that really holds water. And a lot of men ended up saying things like, “Well, you could never disagree with her. She would never allow it.” So how does that work? You couldn’t stand up to her, or you wouldn’t? It seems to me if you disagree with somebody and you don’t say so or you’re afraid to make your case, or you lose the argument every time, that’s not the other person’s fault. And because she was so incredibly brainy, you would get into conversations with her where you couldn’t argue her down. But that’s not the same as saying she wouldn’t allow you to have your own opinion. Someone not allowing you to think for yourself—

DC: Who would want to spend time with someone like that?

DC: Who would want to spend time with someone like that?SZ: Exactly. And how would that even work? It’s like the Eleanor Roosevelt thing—nobody can make you a victim without your consent.

DC: The first time I saw Pauline Kael was on The Mike Douglas Show, and I remember even just as a viewer being kind of intimidated by her because she seemed so smart, she took herself seriously, but she had a sense of humor. I wasn’t used to seeing people who were that composed, so sure of themselves. Then, in college I picked up a copy of Reeling because I recognized her name, and that was all it took. I feel like an important, influential moment in my life can definitely be demarcated at the point where I first encountered that book.

SZ: She was so influential, even to those who don’t like her or consider themselves “fans.” At this point I think it’s really ridiculous that you have to be in the Kael camp or the Sarris camp. Andrew Sarris is a sweet guy and a wonderful critic—it’s just a very different approach. Maybe in the days of “Circles and Squares” you really would have to draw a line in the sand, but at this point perpetuating this feudal sensibility is ridiculous. But at the same time, that people go out of their way to tear her down now- I think it’s pointless. There are still people who think that if you were friends with her or if you were influenced by her, you’re somehow still getting your cues from her from beyond the grave.

DC: Speaking of influence, as you mentioned earlier, you’re married to a film critic. I can’t imagine that you don’t have moments when you disagree with Charlie about something.

SZ: (Laughs)

DC: How does that work for you two? I once posed the question on one of my quizzes, Is there a movie, piece of art, whatever , that should the person with whom you were having a relationship expressed great love for something you thought was a piece of crap, would that be the deal-breaker? And I’ve always wondered that about people in relationships who share a profession in which the cultivation of personal ideas about art is front and center. How does that work? Do you get into a lot of arguments about movies?

SZ: Not so much. Charlie and I share a sensibility. We often tend to like the same things, even though we often don’t like them for the same reasons. That’s one thing that has sometimes been kind of difficult during the course of our relationship and our professional lives. You always hear, “Oh, they always like the same things. Their 10-best lists are always identical.” And often I feel it’s a kind of sexist way of reacting, like saying I can’t think for myself, I take my cues from him—that always seems to be the subtext, and don’t even get me started on that. But we do disagree. For example, recently we went to the screening of Public Enemies, and because there were so many people there we couldn’t sit together. I pretty much liked the movie, aside from some misgivings. Afterward I went out to the lobby and I find Charlie, and he’s kind of fuming and he says, “Somebody needs to kick Michael Mann’s ass!” “So you didn’t like it?" And he starts explaining to me why he didn’t like it. “The camera’s all shaky, and I’m so sick of the shaky camera thing--” “I know, I’m sick of it too.” But it’s interesting—if I’m sitting with him, I can tell whether or not he’s with something. So the fact that we were sitting apart was interesting, because I really didn’t know until afterward. But at this point we’ve known each other so long, disagreements on movies are like anything else—you just talk it out: ”I think you’re full of shit,” or whatever. But the deal-breaker question is an interesting one. I do have a friend who had a girlfriend at one point, and we were out for drinks and talking, and he said, “I showed her The Lady Eve and she didn’t like it.” And I just looked at him said, “Are you sure about this girl?” (Laughs)

DC: Okay, I didn’t think I had one, but you might have uncovered one of my deal-breakers with that little anecdote.

SZ: Yeah, I think that would qualify for me too. And by the way, that relationship did not last, and I knew it wouldn’t. I didn’t want to be too harsh, but—

DC: Somewhat related to that, is there a movie you feel you’ve really had to stand up for when everyone else was booing and hissing? Charlie’s piece on Showgirls really turned my head around on that movie—he was writing about it in a way that no one else seemed capable of, seemed willing to. I didn’t see the movie again for about another couple of years after I read that essay, but when I did it was literally as if I’d never seen the picture before. There was something about the way that he chose to understand that movie, how he took it seriously enough to write about the movie on the screen rather than the one everyone had already decided was so irredeemably bad, that was so unusual and gratifying. I’ve since tried to be as persuasive as he was about Showgirls, but I don’t think it’s had very much of the same effect. Is there a movie like that for you?

SZ: There are a couple. I really loved Masked and Anonymous, the Bob Dylan movie that everyone hated. That thing got universally trashed and it’s considered a fiasco, and nobody ever talks about it now. But I loved that movie. And I remember people who really should have known better coming out of it and saying, “What was that?! That didn’t make any sense! I couldn’t put it together! It wasn’t very linear!” And I kept thinking, have you ever actually listened to a Bob Dylan song? Because there’s really a lot going on in that movie, and it is a little crazy, and it does rattle your head, but, really what kind of movie do you want Bob Dylan to make? Well, I really shouldn’t ask that question, because then you get—

SZ, DC: Renaldo and Clara! (Both Laughing)

SZ: But really, what do we expect from this guy? So, Masked and Anonymous is one. Another one that I really love, which is actually not such a tough sell, I have found out, is CQ, the Roman Coppola movie. I adore that movie because it’s so affectionate. It’s one of those movies that could only have been made by the son of someone whose dad has shown them a lot of weird movies—Mario Bava, Danger: Diabolik, and all that stuff. It’s lovely and beautifully made. No one went to see it in theaters, but when it came out on DVD—When Charlie and I find DVDs really cheap, in the discount bins, five dollars or whatever, if we find something we love we’ll buy up chunks of them and give them to deserving people or people we think might like them. We did that with CQ, and I can’t remember giving it to anyone who didn’t like it. People would watch it and say, “Oh, my God, how did I miss this?” And it’s the only movie Roman Coppola has ever made, as far as I know—he’s primarily a second unit director for other people. I really feel protective of movies like that. Sometimes people can be so automatically dismissive of things. You see something on a bad day, you’re in a bad mood—

SZ: But really, what do we expect from this guy? So, Masked and Anonymous is one. Another one that I really love, which is actually not such a tough sell, I have found out, is CQ, the Roman Coppola movie. I adore that movie because it’s so affectionate. It’s one of those movies that could only have been made by the son of someone whose dad has shown them a lot of weird movies—Mario Bava, Danger: Diabolik, and all that stuff. It’s lovely and beautifully made. No one went to see it in theaters, but when it came out on DVD—When Charlie and I find DVDs really cheap, in the discount bins, five dollars or whatever, if we find something we love we’ll buy up chunks of them and give them to deserving people or people we think might like them. We did that with CQ, and I can’t remember giving it to anyone who didn’t like it. People would watch it and say, “Oh, my God, how did I miss this?” And it’s the only movie Roman Coppola has ever made, as far as I know—he’s primarily a second unit director for other people. I really feel protective of movies like that. Sometimes people can be so automatically dismissive of things. You see something on a bad day, you’re in a bad mood— DC: That was precisely my experience with CQ. I went into it knowing that writers I respected thought pretty highly of it, and I fell asleep midway through. And I put that more on seeing it at home than anything else—the home-viewing environment is, if anything, too comfortable for me at times. I need to take myself out where I know I can’t just flop at will—I automatically feel more aware and receptive in a theater. So when I miss something at home for those reasons, I usually file that movie away and try to get back to it. I don’t want to be dismissive of a movie because it’s usually not the movie’s fault if I can’t keep my eyes open. So I’ll put CQ at the top of that list.

DC: That was precisely my experience with CQ. I went into it knowing that writers I respected thought pretty highly of it, and I fell asleep midway through. And I put that more on seeing it at home than anything else—the home-viewing environment is, if anything, too comfortable for me at times. I need to take myself out where I know I can’t just flop at will—I automatically feel more aware and receptive in a theater. So when I miss something at home for those reasons, I usually file that movie away and try to get back to it. I don’t want to be dismissive of a movie because it’s usually not the movie’s fault if I can’t keep my eyes open. So I’ll put CQ at the top of that list.SZ: Maybe you should look at Speed Racer again…

DC: (Laughs) This is the part where I storm out of the interview.

SZ: (Laughs)

DC: I want to talk a little bit about the interactivity with your readers. You’re in a position as a critic where you hear a lot from people who are reading your stuff. I used to look at the comments after one of your reviews, or one of David Edelstein’s, just to gauge the reaction to what you wrote. But it has gotten to the point where I can almost predict the reaction, particularly if you’re talking about a big blockbuster summer release where many people already have so much invested in the anticipation of the movie, because of marketing or advance write-ups or whatever, that, goddamn it, it’s got to be good, and don’t tell me otherwise. "You knew you weren’t going to like it, so why did you review it?" I get the feeling if you said to your editor, “Gee, I don’t think I’m gonna like this one—"

DC: I want to talk a little bit about the interactivity with your readers. You’re in a position as a critic where you hear a lot from people who are reading your stuff. I used to look at the comments after one of your reviews, or one of David Edelstein’s, just to gauge the reaction to what you wrote. But it has gotten to the point where I can almost predict the reaction, particularly if you’re talking about a big blockbuster summer release where many people already have so much invested in the anticipation of the movie, because of marketing or advance write-ups or whatever, that, goddamn it, it’s got to be good, and don’t tell me otherwise. "You knew you weren’t going to like it, so why did you review it?" I get the feeling if you said to your editor, “Gee, I don’t think I’m gonna like this one—"SZ: Yeah, that would go over really well!

DC: And of course, whenever I see this kind of response to something a critic has written, I always think, why are you reading a serious critic in the first place if you’re going to be so thin-skinned

about they write? Is this attitude something you encounter often?

SZ: I encounter it a lot, but the one thing that I have come to terms with is that there’s a difference between readers and commenters. I often suspect, though this is certainly not true across the board, that those whose reactions are most outraged may have only read the deck, or the first paragraph, and no more. Some people try to engage with the ideas I’ve written about, or challenge a particular observation, but sometimes the comments are weirdly personal or along the lines of, “Oh, she never likes any action movies or comedies.” I’ve been reviewing for Salon since 1996—I could point to any number of exceptions to that kind of assertion. I don’t like to have to make that kind of distinction (about readers vs. commenters), but it’s not like the people who come to your blog who are interested in movies, interested in talking about them and having a dialogue where they want to know what you think. You draw a very specific kind of engaged reader. I’m not saying you don’t get crackpots, because there’s always going to be an element of that. But Salon is very easily accessible from Rotten Tomatoes, for one thing. I think that’s how a lot of people found The Dark Knight review. It’s less that those readers come to Salon every Friday to see what I think. It was more like they went on Rotten Tomatoes and looked for the people who didn’t like The Dark Knight, clicked on those names and came on over. I mostly tend not to read those comments, however. Sometimes I’ll read them months after the fact, just out of curiosity.

DC: Well, it’s one thing if someone is there to present an honest argument or challenge you factually, but really, so many of those kinds of comments I see are from people who are there just to pop off and see their names on the Internet.

SZ: One of the great things about writing for Salon, and this has been true since the very beginning, and I absolutely love this about it, is that people do have access to you. I know it might sound like I’m contradicting what I just said, but I realized in the late ‘90s I would write a review and, hey, people could send me an e-mail! I would get letters—some of them very nice, agree or not agree, and sometimes they wouldn’t be so nice—but sometimes they were just normal, engaged, interesting people who only wanted to be able to make their case. I felt like I had this relationship with them. And now you can’t have an online publication without having that interactive arm where people can just post their comments. And what it means is that I actually get less interaction because fewer people write to me directly. I mean, anyone can e-mail me. But I get fewer letters sent to me directly than I used to because I think people may feel posting a comment is the same thing, or maybe it’s more convenient.

DC: I love that close interaction with the readers I have, but something I don’t get much of here is that kind of interaction with people who seem as if they are actively trying not to understand your point of view.

SZ: Yeah, and the other thing is, I do hear from enough people to know that the people who are actually reading the reviews from start to finish-- and agreeing, disagreeing, it doesn’t matter which—aren’t usually the same ones that are commenting. They’re too busy with their lives. I mean one guy actually went through the archives and his criticism was, “Stephanie Zacharek likes the word ‘hangdog’ an awful lot!” And he did a search and found every time I had used the word “hangdog” in a piece going back to 1997. Maybe there were 10 or 12 instances over a period of 12 years! (Laughs). Somebody actually commented about that and said, “You have too much time on your hands,” and he responded, “It only took three minutes!” Well, even three minutes—

DC: A friend and I have been thinking about something lately, and I would like to know what you think. You, as a critic, seem to be more open, I won’t say to every silly comedy that comes around the bend, but you’ve come to the defense of a lot of silly movies that many critics and moviegoers have just tended to dismiss outright as being beneath consideration or, well, silly. I’m thinking of stuff like the Will Ferrell movies-- Anchorman, or even Land of the Lost, which I suspect I liked more than you did. But I heard people getting actively annoyed by that movie, and I’m curious as to what they expected. Do you get a sense that blatant silliness is more likely to be rejected by audiences these days?

SZ: I think you’re right. Comedy is so delicate.

DC: And maybe this is what accounts for the some of the dourness in our superhero/fantasy movies these days. We don’t take our mythologizing as seriously if there’s a detectable sense of humor involved.

SZ: Comedy is difficult to write about too. That’s another thing.

DC: It’s easy for me to just find myself repeating all the jokes and passing that off as a review. And when you try to figure out why it’s funny, that’s a real show killer.

SZ: That’s one of the great pleasures of the movies is just to give yourself over. “This is ridiculous. Why am I laughing?” Isn’t that what you want? One of my favorite people to see a comedy with is David Edelstein, because sometimes the oddest things will get him giggling. We saw The Animal together, the Rob Schneider movie, which is totally stupid and not very good, but he started giggling at some dumb gag, and then I started giggling—Maybe it could skew your critical judgment, this kind of response, but what does that even mean, if something does or doesn’t make you laugh?

SZ: That’s one of the great pleasures of the movies is just to give yourself over. “This is ridiculous. Why am I laughing?” Isn’t that what you want? One of my favorite people to see a comedy with is David Edelstein, because sometimes the oddest things will get him giggling. We saw The Animal together, the Rob Schneider movie, which is totally stupid and not very good, but he started giggling at some dumb gag, and then I started giggling—Maybe it could skew your critical judgment, this kind of response, but what does that even mean, if something does or doesn’t make you laugh? DC: You write about movies for a living, and movies are an art form that derive their effects and approaches and pleasures from the combination of all of the other arts, so obviously it takes more than just an knowledge of movies to write well about them. What do you like to read about or think about that is not related to the movies that informs your understanding of them?

SZ: Well, I was a pop music critic before I was a movie critic, and for me music is really, really hard to write about. I did it for four or five years on a freelance basis, and it became so difficult that I think I was really ready to give it up.

DC: I credit you and Charlie with turning me on to Fountains of Wayne, by the way.

SZ: Oh, I love Fountains of Wayne! Did you see That Thing You Do? Adam Schlesinger wrote the title song from that movie. I love that. It’s genius. But really, one of the reasons I loved writing about movies is that you could pull together all of these things—literature, sound, music, to an extent. You’re watching what a director is doing, where he or she is putting the camera, what’s going on with the script, the vibe and the strategy of the cinematography. There’s so much going on in movies that I think a steady diet of only movies is very bad. You have to live a life and pursue other interests, because otherwise you have nothing to hang the movies on. I can see how you could get sucked into it though—you could fill up your life just watching movies.

DC: So many film school graduates are adept with a camera, but they haven’t lived a life that they could tell through the films they make.

SZ: Exactly. And that extends to a lot of young critics, who are just all movies all the time. They’ve seen a lot of stuff—sometimes more stuff than I’ve seen. They’re very movie literate, which is great, but you really do have to make room for other things. So I do listen to music, and I read -- probably not as much as I should, but I try to keep up. You know, I really like to sew. It’s hard to find time to do it, but I make a lot of my own clothes. I don’t think it’s related to movies at all, except that I like seeing the way things go together. Fabric is flat, two-dimensional, and I love sewing it into a shape based on a pattern. There’s a lot of problem-solving, and it’s also completely nonverbal—it’s just visual and tactile.

DC: So, how is 2009 shaping up, movie-wise, in your view?

SZ: Well, I don’t think it’s been a particularly great year so far. Often I find that by May or June I have three, four, maybe five movies that might possibly go on my ten-best list. This year, maybe the Assayas movie, Summer Hours, which I think is lovely. Two Lovers, the James Gray movie which, if you missed it, is out now on DVD. Charlie was just waving it in front of my face, like, “Don’t forget this one!”

DC: What did you think of Tyson?

SZ: I haven’t seen Tyson yet, but I really need to. That movie has gotten a lot of interesting and varied reactions. Oh, and The International!

DC: Yeah! I liked that one too. There’s a good example of a movie that seems to have fallen victim to advance received wisdom about it being bad.

SZ: It opened the Berlin Film Festival, and I was there, and the buzz on it was very weird. A lot of the European critics didn’t like it, and I think the sense of it was that Tom Tykwer was this German director of great promise, and he had sort of let people down by making a movie that was too Hollywood. So the American critics in Berlin kind of followed suit because the Americans don’t want to be seen as unsophisticated. Everyone was saying things like, “Oh, The International wasn’t that good,” and I couldn’t believe they didn’t see how subtle it was and how beautiful it was to look at. I found one Italian critic who felt the same way about it that I did, and we kind of clung together and developed these theories about why- I mean, he said he felt European critics just simply thought it was too American. I love going to festivals, and the Berlin Film Festival is particularly lovely, but you are in this world of critics where these professionals become afraid to render a dissenting opinion. There’s a very strong sense that everybody kind of decides what the good movies are—

DC: And that generalized sense of a movie’s worth does filter down to not only critics and executives at festivals, but it also factors into the way the movie is perceived when it’s finally released in the marketplace.

SZ: It’s true, because those of us who don’t go to the festivals look at the festival coverage and make conscious or subconscious note that, oh, this one didn’t get such great notices at Cannes or wherever. I don’t go to that many festivals myself, but since I have been going I’ve learned to take those initial festival reports and roundups with a grain of salt in most cases, because it’s hard not to be affected by your colleagues. Part of that is because it’s a social atmosphere and you are talking and exchanging ideas, and because you don’t have much time you may say to someone, “Have you seen anything good?” And they’ll tell you, “Oh, see Ten Canoes, or see this little Romanian movie.” So in a way you need to have that interaction with other critics, even though it can be a double-edged sword.

DC: It would seem that a lot of it might also come down to your own confidence in your ability to assess things for yourself rather than get swept up in whatever groupthink might be going on. With my blog, I don’t have time to write about everything or see everything, so the ones I usually gravitate toward writing about are the ones that may be overlooked in the shadow of the latest blockbuster, or maybe I have an alternate point of view from the consensus. I’m not trying to be consciously contrarian, and there are plenty of times when I find myself squarely amongst the pack, but I think it’s a worthy challenge to try to consider why my view might be so different from the majority on a given movie. That’s what’s more interesting to me.

DC: It would seem that a lot of it might also come down to your own confidence in your ability to assess things for yourself rather than get swept up in whatever groupthink might be going on. With my blog, I don’t have time to write about everything or see everything, so the ones I usually gravitate toward writing about are the ones that may be overlooked in the shadow of the latest blockbuster, or maybe I have an alternate point of view from the consensus. I’m not trying to be consciously contrarian, and there are plenty of times when I find myself squarely amongst the pack, but I think it’s a worthy challenge to try to consider why my view might be so different from the majority on a given movie. That’s what’s more interesting to me.SZ: And also more interesting to read.

DC: I hope so. If it’s well-written, then maybe there’s a reason to read another article about Up, or whatever it might be. Okay, time to start wrapping this up.

SZ: Yes, it’s almost the cocktail hour! (Laughs)

DC: Indeed! Okay, what would be in your movie hall of fame?

SZ: The Lady Eve. The Apu Trilogy. The Rules of the Game. Um, the Godfather movies.

DC: Even Part III?

SZ: No, no, no. When I say the Godfather movies, Part III does not exist. (Laughs). The Wild Bunch. Um… (Pauses and makes hissing sound while considering other titles).

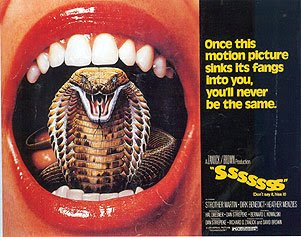

DC: Oh, I thought you were recommending Sssssss!, the snake movie with Strother Martin and Dirk Benedict!

SZ (Laughs) No, not that!

DC: I like that movie!

SZ: Let me see. Also something by Brian De Palma, probably Casualties of War.

DC: Finally, given the events of the past week, do you have any thoughts, as a former music critic or just as an appreciator of pop music, about Michael Jackson? (Jackson died the day before this interview was recorded.)

SZ: Four or five days ago, I just happened to be thinking about “Billie Jean.” I hadn’t heard it in a while, and somehow it got back into my head. My God, what a fabulous, frightening song, you know? And really, I feel like Michael Jackson is somebody we lost long ago. Mourning him at this point is— This is awful to say, but it’s kind of like an afterthought, because I, and so many of us, had to give up on him so long ago. Many times over the years I’d see a film clip of him when he was with the Jackson 5ive, or-- Off the Wall is actually my favorite Michael Jackson period. But when he was little, singing “I Want You Back” or something, I would just look at that face and start to cry. You have this incredible, beautiful kid with an incredible voice and amazing talent as a dancer, even just as a little guy. He was really a born entertainer, but I guess it’s kind of a curse to be a born entertainer in a case like that.

DC: What I find difficult in watching the tributes and people’s attempts to deal with what it is that he meant to them is that so much of it—I mean, to follow the media and the general way the wind has been blowing over the past several years, three or four days ago Michael Jackson was a freak, and now today he’s a saint. There’s an uncomfortable air of sanctimony, especially in the media coverage, after all that’s been written and said. It’s not that I want to wallow in the horrible stuff in this moment. I think I’m just looking for more of an acknowledgment of his complexity.

SZ: You’re not supposed to speak ill of the dead, right? But I feel like when anyone dies, it’s more respectful to consider the whole of the person. I remember going on the Graceland tour 20 or so years ago, and these glassy-eyed girls would be leading you through the mansion telling you all about Elvis’s life--I’m a big Elvis fan, by the way—and they finally get to the end and they would say, (sing-songy falsetto) “Elvis died of a heart attack.” Well, no, actually he died on the crapper. He was messed up toward the end. He had this very difficult, complicated life. And I think they probably thought it was disrespectful to acknowledge that the guy had any problems or idiosyncrasies… but that’s what makes Elvis Elvis-- a human being and a deity, you know, God and man. (Laughs) That might sound cracked, but we do make these people larger than life.

DC: And the way we deal with that aspect of their legacy is the way we should deal with anything that affects us from an artistic perspective. If you only focus on the warm fuzzies, you’re missing so much more of the total picture of what an artist, or a song, or a film can mean. And when you get to read a good writer, like you, you’re reading someone who’s willing to engage with the uncomfortable stuff too. Maybe that annoys some people when you write about popular cinema, but that’s what gets me on your side, your ability to peel the movie back and really look at it, whether it’s The Dark Knight or Summer Hours or Transporter 3.

SZ: Part of it too is that movies have gotten so strange now—there is, I find, less attention to craftsmanship. A lot of filmmakers are making these big budget movies, and they don’t even know where to put the camera—a lot of hand-held camera shaking all over the place. Put it on a tripod for a while.

DC: That was an interesting point in your review of The Hurt Locker, this resistance to what I’ll call classical filmmaking and letting the camera be an observer, putting it in the right spot to amplify what’s going on. I think Kathryn Bigelow is a brilliant filmmaker, but I wanted a little less of the you-are-there jittery camerawork and more shaping of sequences that were more likely to stay in my head visually.

SZ: I was tough on her, and I did like the movie a lot. I would have been more complimentary, I think, had the movie been made by just a random joe. But because it was her, and she is somebody who knows what she’s doing—I mean, it’s actually a pleasure to write about someone who knows what’s she doing, ‘cause then you can look and find certain things like, “Oh, stealing from Paul Mazursky! No, no, no!” (Laughs). But my thing is, at this point I’m just looking for something that’s alive on the screen. Give me something that has some energy to it—and real energy, not just fast cutting. Or even something as relatively simple as making a woman look beautiful, or lighting someone in a certain way, so much of that seems to have been lost. You just have to grab pleasure wherever you can get it.

DC: When I took my daughter to see The Lady Eve, there was a shot of Barbara Stanwyck early on and she turned to me and said, “Is she real? Does she really look like that?”

DC: When I took my daughter to see The Lady Eve, there was a shot of Barbara Stanwyck early on and she turned to me and said, “Is she real? Does she really look like that?”SZ (laughing): That’s great!

DC: I got a real kick out of imagining her mentally comparing the way Barbara Stanwyck looked and was photographed in that movie to the way actors are shot in the movies she’s more used to seeing.

SZ: Because cinematographers then would set lighting up very meticulously, and you would have to be on your mark. So the woman would be lit and placed so carefully and if she moved the effect might be lost, but if she sat or stood still she would seem to be the most beautiful, radiant creature. Same with men too. Someone like Cary Grant is beautiful to begin with, but part of it was the skill of DPs and the lighting guys and the director knowing what he wants. I wish more young filmmakers would rediscover and explore more classical filmmaking technique. I don’t want every movie to be like that, but it would be nice to see them screw the camera into a tripod every once in a while. (Both laugh). See what that’s like! Just try it!

SZ: Because cinematographers then would set lighting up very meticulously, and you would have to be on your mark. So the woman would be lit and placed so carefully and if she moved the effect might be lost, but if she sat or stood still she would seem to be the most beautiful, radiant creature. Same with men too. Someone like Cary Grant is beautiful to begin with, but part of it was the skill of DPs and the lighting guys and the director knowing what he wants. I wish more young filmmakers would rediscover and explore more classical filmmaking technique. I don’t want every movie to be like that, but it would be nice to see them screw the camera into a tripod every once in a while. (Both laugh). See what that’s like! Just try it!

*************************************************

13 comments:

That was a great interview, Dennis. Kudos!

Wow -- SLIFR is always entertaining and provocative, but today I felt like I was at lunch with friends.

Good friends. . . .

Nicely done!

Great interview. I'm glad someone else liked Masked and Anonymous. Nobody complained that I'm Not There didn't make any linear sense. Why the hate on M&A?

Heck, I'd even watch Renaldo and Clara.

Oh, how wonderful! It was even better than I had expected. What a cool, smart person she seems to be; I can imagine you and she would be good friends, if you had the chance (and maybe you are, even long-distance).

Fantastic, Dennis. Just fantastic.

Thanks, all. I had never actually spoken to Stephanie Zacharek before we did this interview. (Lots of e-mails, but that don't count.) Of course, I had some problems getting Skype to work on my end, and I wasn't even aware I had video conferencing capability. We were actually connected for 30 seconds or so before we even knew it, and so I had to announce myself out of nowhere. And once I did I knew immediately she was one of these people with whom I felt almost instantly comfortable. I'm really glad that you all seemed to enjoy reading the interview and that the relaxed vibe seems to have been communicated. She had fun too and has said that she'd be interested in doing another one of these-- maybe an end-of-the-year look back at 2009 session or something along those lines? We'll see! Right now I've gotta take another look at CQ, and finally get to Masked and Anonymous, which even my Dylan-worshiping wife hasn't yet seen. But I stand firm on Speed Racer, dammit...

Next week: Joe Dante returns!

Larry, did you ever see Masked and Anonymous?

Blaaagh: If we'd known Stephanie in college, we would have all been fast friends, I'm sure of that.

Thank you for defending the unrealized masterpiece Speed Racer! If it doesn't achieve cult status in 15 years I have no faith in the critical masses.

Oh yeah, I love Masked and Anonymous because, as she says, it is totally a Dylan song. Which means it's wonderfully weird and discursive, plus you get the sense that all these big movie stars are gobsmacked to be appearing with Bob Dylan. The soundtrack kicks ass, too. It would make a weird companion viewing piece to I'm Not There, which would also make a good title for Masked and Anonymous. I gotta go watch that again now!

And as Larry Charles movies go, it's a lot better than Borat and Bruno.

I'd like to second the kudos for The International. I took my wife, who works in finance, to see it and we both thought it was very entertaining. More importantly, the movie got her respect with the "debt is control" scene. She told me that was dead on.

Really fantastic, Dennis! I teach a film reviewing course every now and then where I work, and I think this interview will be fascinating for the students. It was certainly fascinating for me! (And I love that she remains such a stumper for Masked and Anonymous. We few, we proud!)

NFP: I'm curious. Would you mind saying where you teach film criticism, or in what context? I think Stephanie's perspective as a film critic working in a journalistic mode (that is, beholden to deadlines and timely reporting of movies relevant to the marketplace) is very valuable. She must be able to compose her thoughts and her reasoning very quickly, which is sometimes very difficult to do. It's really great to be able to take a look at a movie after a couple of years, away from all the hype and noise, as I and many other bloggers often do. But to be able to write the way she does in such a time-sensitive situation, with integrity, style and wit, is much more difficult, and exhausting, than I'd bet most of us realize. Thanks for checking in!

Really nice interview, Dennis. And I completely agree with Stephanie, CQ is quite wonderful. Now I really need to see The International!

What an absolutely embarrassing suck-up job this interview is. Not a single tough question asked, not a single moment in which the servile sycophancy is alleviated.

If I had the opportunity to interview Little Ms. Zacharek (the fake, intellectually null, BLADE RUNNER replicant version of Pauline Kael), I'd give her a grilling the likes of which she's never encountered.

What Kael said about Streep in SILKWOOD, that she had the surface mannerisms down pat, but "something is not quite right," and that "she's a replicant, all schtick," is the perfect, dead-on description of Zacharek vis-a-vis Kael. She can fool unobservant and lazy readers into thinking she's the heir apparent to Kael, but it's just an act of shallow replicant mimicry. She's all style and no substance, Kael's synthetic clone, with "no natural vitality."

Post a Comment