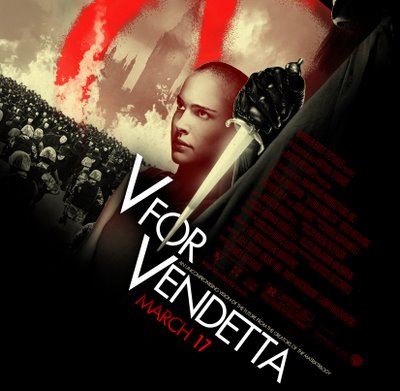

BEHIND THE MASK: MORE ON V FOR VENDETTA

V for Vendetta-- I know, I know, that’s so two weeks ago. But the movie, less than flawless though it may be, has rib-sticking power, and I like the fact that it’s forcing itself to churn and burn around in my head to the degree it has so far. And I really liked the degree of debate that it inspired in my comments column—meager by the standard of some blogs, perhaps, but pretty juicy for the old SLIFR. A couple of points of view came to light in the last week or so, after my original piece had been bumped far enough down the page as to be relatively missable. I liked what I read in these pieces—two from posts on other blogs, the other from a private e-mail from a friend whose permission I have secured so I might reprint his comments here—enough to want to highlight them in their own post and ensure that they didn't get buried at the bottom of a two-week-old item.

************************************************************

First up, David Lowery, proprietor of Drifting had this to say when he checked after reading my post:

”Wonderful review, Dennis, and one which I would have agreed with completely up until I saw the film again the other day. I think it's a fairly successful adaptation of a difficult work, and I admire it greatly for what it does right - but the filmmakers make one or two very crucial errors that essentially dumb everything down, that make the politics subversive on a very surface level (which, granted, is still more than one might expect from an action movie). I'll have a review of my own at my blog shortly in which I go into these issues more throroughly. For the meantime, I'll just say that I'm glad people are seeing it and that it's inspiring so much writing and eloquent, multi-sided discussion - that alone validates the film.”

I was definitely intrigued. I like the process of debating ideas about movies, especially one like this, and I like to think I can keep an open mind about thoughts that don’t fall in line with my own. And that last sentiment was certainly one I could get behind. So I kept my eyes open for David’s own post and, sure enough, a few days later David was ready to go. Here’s a taste:

”It's not the ideology that's problematic, necessarily, but that the Wachowskis and director James McTiegue don't have the courage of their convictions. The film, so revolutionary up to a point, is ultimately unable to commit to the concept of noble anarchy espoused by Alan Moore in the original graphic novel. The film wants to support this, and it makes steps in that direction; but at the crucial point, it sidesteps the issue and reduces a legitimately challenging thesis to something of more Orwellian proportions. Granted, Moore's novel was a polemic against Thatcherian fascism that owed much to 1984, and in preserving a great deal of his solution to Big Brother, the film is quite radical. At the last minute, though, the filmmakers take what it is a very gray area and make it distinctly black and white; after aspiring for intelligent provocation, the Wachowskis settle at the end for inspiration.”

”It's not the ideology that's problematic, necessarily, but that the Wachowskis and director James McTiegue don't have the courage of their convictions. The film, so revolutionary up to a point, is ultimately unable to commit to the concept of noble anarchy espoused by Alan Moore in the original graphic novel. The film wants to support this, and it makes steps in that direction; but at the crucial point, it sidesteps the issue and reduces a legitimately challenging thesis to something of more Orwellian proportions. Granted, Moore's novel was a polemic against Thatcherian fascism that owed much to 1984, and in preserving a great deal of his solution to Big Brother, the film is quite radical. At the last minute, though, the filmmakers take what it is a very gray area and make it distinctly black and white; after aspiring for intelligent provocation, the Wachowskis settle at the end for inspiration.”What’s fascinating about Lowery’s approach is that for all of his exposition of what he sees as the film’s flaws, he still makes a reader want to see the film for their own experience with it. In fact, by the time he concludes his own comments, he’s ready to see the film again and enjoy it and admire it despite his own criticism. Check out David Lowery on V for Vendetta and enjoy a very good writer grappling with a very provocative film.

**********************************************************

The second piece, entitled “The Smallest of Killings: The Public Sacrifice of Alan Moore and V for Vendetta,” fooled me. Posted on Chris Stangl’s blog The Exploding Kinetoscope, I admit I was expecting another anti-Wachowski tirade from yet another angry fan of the graphic novel. Instead, the article serves up the perspective of a very levelheaded appreciator of the graphic novel who attempts to see what film adaptation does to the original work, how it filters and/or alters the original ideas, and what the film ends up doing apart from the original work. Here are a couple of choice excerpts, the first considering how the film compares to Moore’s storytelling strategy:

”There’s no way for a narrative film to get away with the kind of radical formal experimentation of Moore’s novel. This is a book in which a chapter is structured as sheet music, for random example. But retained are Moore’s trademark impossibly complex networks of visual motifs, echos and mirrors; in Vendetta, the flashiest is the letter V itself, showing up as graffiti, as crossed knives, as a massive row of dominos, as a smear of blood, as a Roman numeral on a prison cell, and in a crucial moment, in the linked arms of two young lovers. The film cannot best the novel’s exhaustive inventiveness, but when the parallel rebirth of Evey in a nighttime rain, and V’s origin story by fire are startlingly intercut, it demonstrates a respectful attempt to retain a sense of Moore’s craft.”

And then, on the film’s point of view:

”It seems to me that V for Vendetta is primarily about how fascism works, how it happens, and a warning that it is the complicity of a citizenry that will allow it to happen again. There are other important questions posed, about the tensions between individuality and nationalism, about media manipulation, about the fate of ill-mounted revolutions. But that’s the core idea. While the celebratory blowing-up of Parliament at the film’s finale, it must be admitted, is unequivocally “positive,” there is never the assumption that V’s means have justified his ends. He spends equal time carefully preserving works of banned art, but destroys beautiful historic architecture; he teaches Evey the power of personal spiritual freedom by torturing her; he cultivates extinct roses only to use them as calling cards for murder: V can only understand art and people as the ideas they symbolize. He can only love or do violence to them based on that relationship. It’s a shortcoming for a human being as much as it is a strength for an activist. And so Vendetta asks: IS this guy right?”

”It seems to me that V for Vendetta is primarily about how fascism works, how it happens, and a warning that it is the complicity of a citizenry that will allow it to happen again. There are other important questions posed, about the tensions between individuality and nationalism, about media manipulation, about the fate of ill-mounted revolutions. But that’s the core idea. While the celebratory blowing-up of Parliament at the film’s finale, it must be admitted, is unequivocally “positive,” there is never the assumption that V’s means have justified his ends. He spends equal time carefully preserving works of banned art, but destroys beautiful historic architecture; he teaches Evey the power of personal spiritual freedom by torturing her; he cultivates extinct roses only to use them as calling cards for murder: V can only understand art and people as the ideas they symbolize. He can only love or do violence to them based on that relationship. It’s a shortcoming for a human being as much as it is a strength for an activist. And so Vendetta asks: IS this guy right?”There’s much more in Stangl’s very well written and reasoned piece, and it’s worth checking out at his appropriately titled blog The Exploding Kinetoscope.

**************************************************************

The other notes I found well worth passing on came in a private e-mail to me last week. They specifically referred to some of the comments made in the wake of my own thoughts on the film. But the main reason I wanted to publish them is because they convincingly offered a response to one of my major complaints about the film. Here’s what I said:

”V For Vendetta is by no means perfect. When Evey's friend, a host of a national TV talk show, played by Stephen Fry, stages a brutal satire of dictatorial figurehead John Hurt (seen throughout the film mostly on video monitors invoking the spirit, if not the letter, of 1984's Big Brother), it seems a crucial misstep that he so arrogantly misjudges the dictatorship's willingness to come directly to his home and shut him down permanently. The incident is used to remind Evey of the abduction and execution of her own parents and lay the groundwork for her own imprisonment, but it's a narratively sloppy way to achieve those ends. Fry's character, who functions largely as a safe-and-sane harbor for the fugitive Evey, for all intents and purposes an above-ground mirror version of V, could have easily served as more than just a ill-thought-out plot device. (I'll be interested to see if the comic book makes the same mistake.)”

I haven’t made it far enough along into the book to know whether or not this development is taken whole hog from Moore, but even if it is I doubt I’ll still be thinking of it as a “mistake,” thanks to these thoughtful comments and their ability to open my eyes a little bit:

”One thing I wanted to say about Stephen Fry's character... The way I interpreted his staging of the satire of John Hurt's character is that Fry's character does what he does because he's simply tired of wearing the mask of the jolly funny man for the state-run network. He knows that he will be put out of his misery once they find his copy of the Koran, and he doesn't care because he's weary of lying about who he really is and lying to the viewing public by distracting them from the horror that exists all about them. His celebrity has given him comfort and the ability to collect things, but he has to put on a front because it is expected of him, and all those pretty things have to be kept locked behind closed doors. And given that the Wachowskis are such private guys, and that one of the brothers maintains an alternative lifestyle that most people would find peculiar, I think it's safe to say that Fry's character mirrors one or both of them more than he mirrors V.”

”One thing I wanted to say about Stephen Fry's character... The way I interpreted his staging of the satire of John Hurt's character is that Fry's character does what he does because he's simply tired of wearing the mask of the jolly funny man for the state-run network. He knows that he will be put out of his misery once they find his copy of the Koran, and he doesn't care because he's weary of lying about who he really is and lying to the viewing public by distracting them from the horror that exists all about them. His celebrity has given him comfort and the ability to collect things, but he has to put on a front because it is expected of him, and all those pretty things have to be kept locked behind closed doors. And given that the Wachowskis are such private guys, and that one of the brothers maintains an alternative lifestyle that most people would find peculiar, I think it's safe to say that Fry's character mirrors one or both of them more than he mirrors V.”The reader went on to wonder whether it was the filmmakers or their corporate sponsors who were making the kinds of explicit links to the Bush administration that SLIFR regular That Little Round-Headed Boy was hearing some reviewers claim, links that he was not seeing in the film itself:

“That Little Round-Headed Boy put forth his take regarding links to the Bush administration, suggesting that the moviemakers themselves might have started that particular discussion. I think that it was Time-Warner, and not the Wachowskis, who started the whole thing. While they stopped short of featuring the movie on the cover of Time, they did devote two pages to the controversial nature of the film (and a sidebar review that was very favorable), and they didn't shy away from mentioning the current administration and 9/11. Odd, but the other day I was thinking how 9/11 has eclipsed so many things, like the Oklahoma City bombing, where a terrorist with an ax to grind with the government and explosives consisting of or derived from fertilizer leveled the federal building. Anyway, TLRHB said that he'd give credit to Spielberg for, I guess, being able to weave politics into his art, I'd have to disagree. The Wachowskis seem a whole lot braver than Spielberg, who really chickened out in Munich in my estimation, not that I expected him to do otherwise.”

Finally, the reader took issue with the Alan Moore quote cited by Benaiah at the end of his own negative assessment of the film in the comments section of my post.

Finally, the reader took issue with the Alan Moore quote cited by Benaiah at the end of his own negative assessment of the film in the comments section of my post.Benaiah said:

“I keep meeting people who love this movie, and my only solace in my bitterness after seeing what they did to Moore's brilliant work is a quote from the author himself: Interviewer: ‘How do you feel about Hollywood ruining your work?’ Moore: ‘What are you talking about? They didn't ruin my work. It is right up there on the shelf.’”

I thought Moore’s quote was funny and, if somewhat maddeningly egocentric, then also a fairly clearheaded way of separating his own work from the adaptation without trying to make it seem like a successful adaptation was an impossible proposition. (Of course, this comment is taken out of context from the interview in which it originally appeared, and it is well known that Moore’s general attitude approaches just that level of artistic arrogance.) But the reader, in his e-mail, thought a whole lot less of Moore’s response than either I or Benaiah did and wasn't too shy about saying so:

”That quote by Alan Moore is just glib shit. It's what I would expect of a writer who sounds pretty talented as well as quite full of himself. If you're a fan of his and his books, a quote like that makes you say, "Yeah, way to zing 'em!" But what writer under the sun looks forward to having her/his work adapted? And, in the case of this particular work, to have one of the biggest communications conglomerates in world release the dang thing-- man, irony is just cold.”

******************************************************************

V for Vendetta may have fallen off the average moviegoer’s radar in time it takes to say Ice Age: The Meltdown, but thoughtful comments like these, and writing like that found on David Lowery and Chris Stangl’s blogs, work to ensure that the tangled, complex responses inspired by the film, and the graphic novel, have a chance to get worked out, or at least massaged and further twisted around to encourage the squeezing out of as much intellectual juice as the film will allow. I still think it’s a terrific movie, and I look forward to wrestling with it again sometime soon.

6 comments:

Well, Dennis, I can't totally remember what I disliked about the movie at this point, but it doesn't stick with me at all, sorry to say. In the end, I just don't get what it's really trying to say, other than we hate the current government's actions. That's fine, but let's not mistake it for deep discourse. What does that V FOR VENDETTA ending signify, anyway? That if we disagree with the current administration, we should go burn down our public buildings? A public rally, even with cool masks, I can get behind that. But mass explosions? Sorry, that's simple-minded. Again, while anarchy is very popular in action movies, in real life disaffected Democrats just need to find a viable candidate. I just think it's a comic book movie, in the best sense of the phrase, and the marketers are trying to add a patina of political/ripped from the headlines depth to goose the box office. No harm, no foul. BUT, while a decent entertainment that didn't leave me feeling ripped off, it certainly didn't leave me feeling I'd gotten the video equivalent of a year's worth of FOREIGN AFFAIRS magazine.

Also I don't get your anonymous poster's thrashing of Moore as being "glib." I'm sure Moore's a difficult egomaniac, what writer isn't?, but this time he seems accurate. For a writer, the book should be sufficient. By the way, and I thought I had mentioned this earlier, you'll find the Stephen Fry character isn't in the graphic novel, though a different kind of broadcaster is.

In the end, maybe V FOR VENDETTA is best looked upon by some, not me, as a tabula rasa that you can project your own ideas about our current state of affairs. I can live with that. Also, I'll stick with MUNICH because in the end, while I didn't love the movie, it asked in a reasonable way if violence is the answer. It didn't have any answers, but it also didn't pretend to have any answers.That to me has more humanity than anything raised by the pyrotechnics of V FOR VENDETTA. (Although I wish they had explored the idea of the fingermen more, now there is something you could hook to today's headlines.)

OK, that should be enought to set off another debate, eh? Peace and love, TLRHB.

I don't think most people see V for Vendetta as a primer on political activism, nor do I think the filmmakers intended it as such. It is, first an foremost, a smashing entertainment, albeit one that has something on its mind. I really think Chris Stangl is onto something as to what that something is, which is why I highlighted it:

"While the celebratory blowing-up of Parliament at the film’s finale, it must be admitted, is unequivocally “positive,” there is never the assumption that V’s means have justified his ends. He spends equal time carefully preserving works of banned art, but destroys beautiful historic architecture; he teaches Evey the power of personal spiritual freedom by torturing her; he cultivates extinct roses only to use them as calling cards for murder: V can only understand art and people as the ideas they symbolize. He can only love or do violence to them based on that relationship. It’s a shortcoming for a human being as much as it is a strength for an activist. And so Vendetta asks: IS this guy right?”

As I stated in my comments on the previous post, I think the film missteps in not making that ambiguity a little clearer, what with Portman and Rea staring out over the explosions and there being just a touch too much triumph in the tone at that point.

My e-mailing friend brings up the same questioning attitude when he remembers Timothy McVeigh (whose actions are specifically alluded to in V for Vendetta with that unmistakable close-up of the fertilizer packed into the subway train that will deliver the film's "celebratory" destruction of Parliament.) Why remind us of McVeigh if you're also expecting us to just swallow V's methods as dependable, righteous or otherwise translatable into a current-world situation?

No, I wouldn't say the movie has the depth of a year's worth of Foreign Affairs magazine, and perhaps not even the depth of Moore's original work (I'm still coyly abstaining for an opinion on that as I haven't yet finished it.) But I think the filmmakers would also be the first to admit that their work is no substitute for impassioned political discourse in the real world. I think they'd be satisfied if their narrative of extreme political resistance and reaction stirred the intellects of its viewers enough that they would ask themselves simple, basic questions about the events (and the motivations behind them) that they witness in the film. Because McTeigue and the Wachowskis (and perhaps-- here's that qualification again, Moore) create a film centered around a swashbuckling terrorist with revenge on his mind as much as revolution, that doesn't necessarily mean they are endorsing V's behavior, any more than Martin Scorsese is advocating crushing someone's head in a car door or dragging a spouse or girlfriend by their hair and beating the shit out of them because they might have been unfaithful by making a film about Jake La Motta, no matter how much Scorsese might identify with the existential, inarticulate rage of his chosen protagonist.

Myself, I still think Moore's comment is a rather creative way of diverting attention from a work he didn't otherwise want to publicize by refocusing on the original work. But it does also make me wonder what Moore's role in making these works available for adaptation. Do you, or does anyone else, know if Moore has had involvement up to a certain point in the production of these films of his graphic novels that he has ultimately distanced himself from or otherwise disowned?

And I'm probably more enthusiastic about Munich than perhaps you are, and more certainly my anonymous e-mailing friend is. I thought it was a pretty compelling, deft way of dealing with some pretty sticky questions about the nature of vengeance and violence, all within a thriller-based structure than I found more than just casually involving. No, Munich didn't pretend to have any answers, and it successfully got a debate going about the righteousness of both the Israelis and the Palestinians, and whether it was possible to ever find ground zero for the questions it raises. I don't think, as you might, that V for Vendetta thinks it has the answers either. Maybe it's those pyrotechnics, its primary positioning as a big-budget action movie, that make it seem more simpleminded than at least I think it is.

At any rate, as much as I agree with your notion that real change should and must come through the strengthening of weak-kneed political parties to serve their constituencies with viable, intelligent candidates, I'd be willing to bet that McTeigue, the Wachowskis, and even Moore would be glad to see this kind of discussion going on, that on some level it is a valuable by-product of their work, as opposed to audiences marching out of theaters and destroying federal buildings with homemade bombs.

Well, Moore doesn't own the copyright on V for Vendetta; that's owned by DC (same with Gaiman and Sandman). So the most he can do is ask for the comic not to be made into a movie, but if DC and Time Warner, part of the same AOL/TW mechamonster, want it done then it's going to happen.

Essentially Moore's pissed that he was accused of being a shill for the LXG film, and so he's washed his hands completely of all films made from his work, including the money, having the other principals split his part up amongst themselves. With films like League of the Extraordinary Gentlemen and Constantine made from his work, I can hardly blame him. At any rate, Neil Gaiman has written about it a bit--he and Moore are friends--and here's what he has to say about it.

Gaiman, for his part, has been lucky not to have had a Sandman film made so far, as a two-hour movie of that work would suck as bad as The Odyssey as done by Hallmark.

The Moore quote about his own works being on the shelves still is actually a bit of plagiarism. It was cited in Stephen King's Danse Macabre, published in the mid-1980s, as by one of the main hardboiled authors whose films were so often made into noir films. I can't remember which it was, though.

Tuwa:

I'm off to my copy of Danse Macabre to see if I can find out who Moore think is sharp enough to steal from! And thanks for the Gaiman link too. I'm really enjoying Moore's original graphic novel, but, as with most reading these days, I'm having to take it fairly slow. My wife bought the paperback edition for me, which is not printed on the glossy sheets like (I assume) the hardback was, but instead on lower-resolution paper in which some of the detail in the illustrations is undoubtedly lost, but which looks, feels and smells like the comic books I used to rabidly consume in the '60s and '70s. I like it!

I hope you'll come back around for Professor Van Helsing's spring break quiz!

I'm a bit late on this, but I believe the quote in question was originally spat out by James M. Cain, in response to a journalist egging him on about a perceived butchering of "The Postman Always Rings Twice".

I'm amazed to see TLRHB putting everything I've thought about the film into words... and more. Yeah, maybe I'm really missing something here, but V For Vendetta just didn't blew me away as I've thought it would have. Hmm.

Post a Comment