ROBERT ALTMAN IN THE REAR-VIEW MIRROR

On the short list of film directors whose work helped develop and change my way of watching film, receiving imagery, and then processing the ethereal, combustive collision of often melodious, often contradictory impulses generated by the world of the film itself, Robert Altman has to be at the top. Altman changed not only the way I saw movies-- his movies helped change the life I lived while I was watching them. When I entered college, Altman's films (at least the two or three I’d seen up till then), and especially the chattering of his enthusiastic disciples, were to be endured, momentarily rest stops on a journey of learning and consuming all the sorts of cinema and literature I already knew that I loved. By the time I left my university world behind, Altman’s movies had transformed for me into dreamscapes of satirical, cacophonous beauty and brazenness and bad behavior, worlds worth not only stopping for but diving into. And they had helped transform me into a more thoughtful viewer, someone capable of more easily embracing a perspective on the world that differed from the one I was used to, someone more willing to bring my own intelligence to the party and understand that that was where the greatest pleasures of the movies lay in wait.

A little over seven years since his death and release of his last movie, most of Altman’s output is available through the usual home video formats—DVD, Bu-ray and streaming are the ways we end up seeing the greatest variety of films in 2014, though it’s hard for me to imagine that it’s even possible to appreciate the crowded splendor and aural fascination of Nashville or McCabe and Mrs. Miller or Buffalo Bill and the Indians on an iPhone. Finding an opportunity to see them projected, as they all were upon their initial releases and throughout the checkered history of repertory cinema in the 40-or-so years since, is a much spottier enterprise, so much so that any opportunity to be there when it happens in this grand digital age should be seized without hesitation.

Such an opportunity has arrived for viewers in Los Angeles, courtesy of the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Beginning tonight and stretching through June 29 the archive has mounted an impressive career retrospective of the innovative, challenging, maddening and rapturous work of Robert Altman, all films screening at the Billy Wilder Theater with the Armand Hammer Museum in Westwood. The schedule is far-ranging and satisfying, even if it is perhaps incomplete—several of his lesser-regarded features from the mid ‘80s, such as H.E.A.L.T.H, Streamers, Fool for Love, Beyond Therapy and O.C. and Stiggs, have been left out, as have been the Pinter adaptations of The Laundromat and The Dumbwaiter which aired on ABC during this same period. But any Altman program which includes a slot headed up by Pret-a-Porter (1994), widely considered to be one of the director’s flimsiest, most misguided trifles (I love it, by the way), cannot be accused of hiding under the covers. (Easily my favorite pairing of the entire festival is the inspired matchup of McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Quintet.)

Perhaps the greatest lure for fans of Altman’s work, who have voraciously consumed books like Patrick McGilligan’s biography Jumping Off the Cliff or Mitchell Zuckoff’s more recent Robert Altman: The Oral Biography is the chance to see some of the director’s earliest achievements as a filmmaker, culled from the catalog of industrial films he did in Kansas City for the Calvin Company while building up to his big break in Hollywood. These rarities, borrowed directly from the director’s own collection which was donated to the UCLA archive after his death in 2006, provide glimpses of the birth of the Altman style, and they include gems like Modern Football (1951), considered to be the director’s first real movie, The Perfect Crime (1955), A Honeymoon for Harriet (1950), The Model’s Handbook (1956), The Kathryn Reed Story (1965), a short Altman made about his wife, and a restoration of a bare-bones backstage musical co-written by Altman called Corn’s-a-Poppin’ (1956). There’s also a collection of Altman’s work for television, including episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Route 66. And speaking of restorations, among the festival’s many highlights are two full-scale restorations performed by the UCLA Archive—the disturbing psychological drama That Cold Day in the Park (1969) and 1982’s Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean.

Here’s the full schedule. You can click on the links for tickets and more information.

April 4 (tonight!): Nashville (1974), plus four-minute short Color Sonics CS-2010: The Party. In attendance: Kathryn Altman, Richard Baskin, Ronee Blakely, Elliot Gould.

April 5: The James Dean Story (1957) and The Delinquents (1957), plus Alfred Hitchcock Presents "The Young One." In attendance: Lew Bracker

April 7: A Perfect Couple (1979) with The Kathryn Reed Story (1965). In attendance: Paul Dooley.

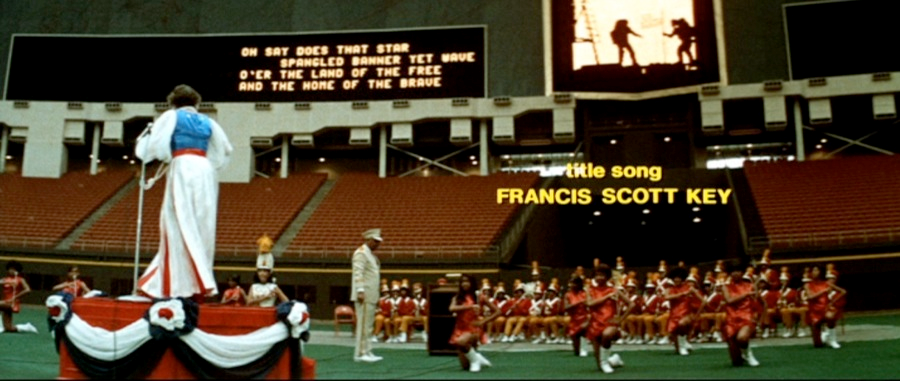

April 11: Brewster McCloud (1970), with Behind the Scene s of Brewster McCloud, some silent footage of Altman and crew on the set of the film working with some of the complicated mechanical effects needed for the movie’s conclusion in the Houston Astrodome. In attendance: Rene Auberjonois.

April 13: 3 Women (1977) and Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982). In attendance: Dennis Christopher

April 19: Countdown (1968) with Modern Football (1951)

April 26: M*A*S*H (1970) with Pot au Feu (1965), a four-minute short starring Altman and others in which they expound upon a glories of the everyday joint. In attendance: Michael Altman, Corey Fischer, Danford B. Greene, Tom Skerritt.

May 3: Pret-a-Porter (Ready to Wear) (1994), with two rarities: Altman’s Color-Sonics short Girl Talk (1965) and Go to Health (1980), a rarely-seen promotional documentary on the set of Altman’s even more rarely-seen feature comedy H*E*A*L*T*H.

May 4: A night devoted to Selected Industrial Films from the Calvin Company, including Corn’s-a-Poppin’ (1956), A Honeymoon for Harriet (1950), The Magic Bond (1956), The Sound of Bells (1952), The Model’s Handbook (1956) and The Perfect Crime (1955).

May 11: A Wedding (1978), plus a 1978 segment from the Dinah! show in which hoist Dinah Shore interviews Altman on the set of A Wedding and gets more than she expected from her subject. In attendance: Dennis Christopher and Paul Dooley.

May 17: Secret Honor (1984), plus a film of Frank South’s play Precious Blood (1982), directed by Altman on the stage and starring Guy Boyd and Alfre Woodard. In attendance: Phillip Baker Hall.

May 29: California Split (1974) and The Long Goodbye (1973), plus Color Sonics short Ebb Tide (1966) featuring burlesque dancer Lili St. Cyr.

June 1: Altman and Television (Free admission): Alfred Hitchcock Presents "Together" (1958) starring Joseph Cotton; Route 66 "Some of the People, Some of the Time" (1961) starring Martin Milner, George Maharis and Keenan Wynn.

June 7: Short Cuts (1993), plus Color Sonics short "Speak Low."

June 9: Thieves Like Us (1974) and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's Sitting Lesson (1976).

June 15: Images (1972) and That Cold Day in the Park (1969), plus Damages (2001), a 16mm movie shot on the set of Images.

June 20: In advance of its cable screening, Ron Mann’s documentary entitled Altman (2014), an original movie shot for the EPIX channel examining the legacy and influence of Robert Altman, with appearances by Paul Thomas Anderson, Philip Baker Hall, Lyle Lovett, Michael Murphy, Lily Tomlin and more.

June 25: Vincent and Theo (1990), plus Zinc Ointment (1971), another short 16mm film by Marianne Dolan (Damages), this one shot on the set of McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

June 27: McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) and Quintet (1979).

June 28: Gosford Park (2001).

For more on the individual films from my perspective, I direct you to one of the first major undertakings of this blog, a four-part tribute to and account of my personal history with the films of Robert Altman, some of which, as in the case of McCabe and Mrs. Miller, has been seriously augmented since this writing on the occasion of his 81st birthday in March 2006. Also, there is below a link to the impromptu words dashed out upon hearing of his death just a few months later, in November 2006.

81 Candles for Robert Altman (Part 1)

81 Candles for Robert Altman (Part 3)

***********************************************

No comments:

Post a Comment