SICK THOUGHTS ON THE OSCARS AND OTHER MATTERS OF IMPORTANCE

UPDATED 1/31/11 4:33 p.m.

You’re very excited, aren’t you? You’ve just settled into your seat after being in line for about an hour. The house is packing up quickly in anticipation of a rare screening of that cult film you’ve only seen on VHS and DVD up till now, and what’s more, the director, the screenwriter and a few other luminaries involved in the making of this favorite film of yours are all scheduled to appear in person to discuss it. You’ve got a great seat, seven rows back from the front, popcorn already purchased, all necessary pees taken. Yep, this is a little bit of paradise. The lights dim, the movie starts…

And so does the coughing. You’re so caught up in the crucial first moments of this film you love so much, you barely even notice it. But after 10 straight minutes of hacking courtesy of a guy seated a mere row and a half away from you, followed by the inevitable nervous shuffling and murmuring of everyone else in the immediate area, the spell, if it was ever really cast, is broken. All you can think about is this hacking, wheezing, phlegmy son of a bitch and how you’d give anything if he’d just take his bronchial circus home to a warm bed and a shot of hot Irish whiskey and leave you and everyone else in peace.

I am that hacking, wheezing, phlegmy son of a bitch.

But I have tried to keep my infectious projections to myself rather than taking them on the road, which is why, even though I had tickets for this past Sunday, Monday and Friday’s screenings I have managed to miss everything good and decent being offered this week by the New Beverly Cinema and the Wright Stuff II series. From Frenzy and Dressed to Kill (both brilliant prints, I understand), to Walter Hill and Bruce Dern introducing a very rare screening of The Driver, to a surprise appearance by David Lynch and Laura Dern and Hill’s second visit during the week, along with actor James Remar, to introduce The Warriors-- yep, I missed ‘em all! I’m trying to take the high road and look at it all as a lesson in selfless courtesy to my fellow man, which works just fine until I start thinking about all the wonderful stuff I must have missed. No calming fog of Vicks Vap-o-rub could possibly compete with listening to Walter Hill talk about The Driver, could it?

Well, in the real world, yes, I suppose it could, really. Here it is, the last Sunday of Edgar Wright’s series, and I’m still coughing a bit, especially in the morning. But confronted with a stout regimen of antibiotics the dragon has been, if not completely silenced then at least appeased for the most part, enough so that I am actually considering venturing out for tonight’s closing program of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (from whence comes the cute and fuzzy image above) and Miami Blues. But much will depend on the how the weight in my chest is sitting come 5:30 or so, when time to consider actually jumping in the car and making the drive over the hill actually arrives. And it’s raining in Los Angeles again today (what did we ever do to deserve such a treat?), and it’s cold in my house, so I may find solace right here at the keyboard writing to you, a tumbler of that warm Irish whiskey at my side, a much more seductive proposition. It has been a long time since I’ve been able to just sit down to bring forth random thoughts from my keyboard rather than random chunks of lung from my outraged respiratory system. And I do have a few thoughts to collect before finally marshaling my resources for the big year-end piece. (Yeah, I know, it’s February. Let go, let go…) So let me spend some time with those bits and pieces, stuff I think you might enjoy with me as the rain falls, and we’ll see where the day takes us…

Well, in the real world, yes, I suppose it could, really. Here it is, the last Sunday of Edgar Wright’s series, and I’m still coughing a bit, especially in the morning. But confronted with a stout regimen of antibiotics the dragon has been, if not completely silenced then at least appeased for the most part, enough so that I am actually considering venturing out for tonight’s closing program of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (from whence comes the cute and fuzzy image above) and Miami Blues. But much will depend on the how the weight in my chest is sitting come 5:30 or so, when time to consider actually jumping in the car and making the drive over the hill actually arrives. And it’s raining in Los Angeles again today (what did we ever do to deserve such a treat?), and it’s cold in my house, so I may find solace right here at the keyboard writing to you, a tumbler of that warm Irish whiskey at my side, a much more seductive proposition. It has been a long time since I’ve been able to just sit down to bring forth random thoughts from my keyboard rather than random chunks of lung from my outraged respiratory system. And I do have a few thoughts to collect before finally marshaling my resources for the big year-end piece. (Yeah, I know, it’s February. Let go, let go…) So let me spend some time with those bits and pieces, stuff I think you might enjoy with me as the rain falls, and we’ll see where the day takes us…Of course, the biggest, most insistent elephant in the room right now is that strange tribal phenomenon known as the Academy Awards. I was discussing the elephant with a good friend of mine over breakfast yesterday, and one of the first things he mentioned was how he never trusts anyone who, upon news of the nominations being announced, said something like, “Oh, I wasn’t even aware the nominations were being announced this morning, so when the phone rang at 5:30 I just thought to myself, ‘Who on earth could be calling at this hour?’” It is awfully hard to swallow that anyone who might actually expect that an Academy Award nomination might be in the cards would be surrounded by a phalanx of publicists and agents so lame as to let them enjoy even one moment’s ignorance regarding the impending announcements. It’s an awfully big pill to swallow to be asked to believe that Natalie Portman, Ryan Gosling and Christian Bale, to name just a few, weren’t if not completely awake at 5:30 this past Tuesday morning, then at least extremely aware of what was coming at dawn when they went to bed on Monday night. My thoughts always go to the people I figured were sure things who, as it turned out, were anything but. Hopefully Lesley Manville wasn’t sitting by her phone waiting for it to ring. Hers was the name that most quickly jumped out at me as missing from the ranks of deserving nominees this year.

In fact, the list of deserving actresses from whom there was no room at Oscar’s Inn this year is a fairly stunning one, especially considering that Meryl Streep didn’t make a movie this year—in addition to Lesley Manville for Another Year, what, no love for the highly touted Tilda Swinton in I Am Love, Catherine Keener in Please Give, Hye-ja Kim in Mother or Emma Stone in Easy A? Yeah, yeah, I know—Manville had some critics awards giving her momentum, but the movie hasn’t made a huge splash even on the art house circuit; Swinton and Kim starred in movies that were so far off Oscar’s radar it’s as though they were never even made; and everybody knows that an actor like Stone has to amass a drawer full of great comic performances to even get a sniff from Oscar, the great inhale coming when said masterful comic actor dives deep into a dramatic role that ignores the elements which made their previous performances so joyful but will finally get them taken seriously by the givers of the gold. Still, goddamn it, they were great performances, any of which could easily supplant that of our hee-hawing, genially goofy front-runner. (And speaking of supplanting, I’ll just come out and say right now that, as much as I enjoyed Annette Bening’s work in The Kids Are All Right, it strikes me as a bit too cleanly worked out and modulated compared to her downright thrilling, much more complicated performance in Rodrigo Garcia’s Mother and Child.)

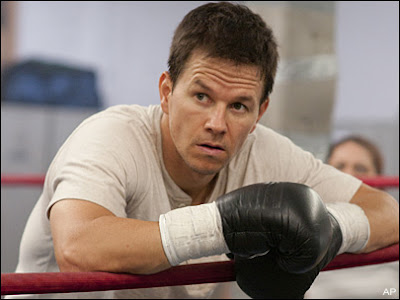

In the best actor category, neither will win, but I’d boot James Franco in favor of Mark Wahlberg’s understated calm at the eye of The Fighter’s familial hurricane any day of the week. And it’s Wahlberg’s centered performance that makes room for the more lionized, outsized work of Christian Bale and Melissa Leo, both of whom are likely to take home statuettes at the end of February. Bale’s “Look, ma! No hands!” brand of acting skirts the edges of “too much,” but the emotional core of the work (”inspired by true events”) keeps it within the ring as demarcated by director David O. Russell. But Melissa Leo’s fiery brand of lower-middle-class motherhood almost always had me averting my eyes. The actress, current poster rep for glum indie self-seriousness, is funnier than she’s usually allowed to be in The Fighter, but from the bouffant on down her working-class matriarch rarely challenges the boundaries of the cartoon manner in which the character has been conceived. I prefer Amy Adams’ smoldering Irish anger, and with that body, doughy in the middle but slightly wider than usual in the shoulders, maybe from hoisting all those beers for the regulars at the local pub, I’d lay money on her taking Leo in a no-holds-barred grudge match without hesitation.

That said, my vote, of the five nominated, would go to Hailee Steinfeld, whose work in True Grit is every bit the equal of Jennifer Lawrence, and her part every bit as central to the film as Lawrence’s. Yet Steinfeld is somehow a “supporting actress” while Lawrence enjoys “Best Actress” status. Based on the running times alone, one would have to guess that their screen time is comparable, and certainly neither film would have worked nearly as well without the actresses who played those roles. But because one actress’s face seems to be more marketable as the face of the film, she gets the push for a lead actress nomination without having to worry about faces from her own picture competing for the spotlight, whereas Steinfeld is looked at as secondary to Bridges and the Coen Brothers as the marketable stars of True Grit. Obviously the thinking isn’t entirely misguided (in terms of rooting out awards anyway) because both women got their deserved nominations. But just imagine the head scratching if Jennifer Lawrence had snared a Best Supporting Actress nomination for Winter’s Bone. Would it have been anything other than laughable? I hope that by the time the winner is announced in Lawrence’s category, Hailee Steinfeld has already had lots of time to smudge up her Oscar as the evening’s first triumphant Best Actress.

That said, my vote, of the five nominated, would go to Hailee Steinfeld, whose work in True Grit is every bit the equal of Jennifer Lawrence, and her part every bit as central to the film as Lawrence’s. Yet Steinfeld is somehow a “supporting actress” while Lawrence enjoys “Best Actress” status. Based on the running times alone, one would have to guess that their screen time is comparable, and certainly neither film would have worked nearly as well without the actresses who played those roles. But because one actress’s face seems to be more marketable as the face of the film, she gets the push for a lead actress nomination without having to worry about faces from her own picture competing for the spotlight, whereas Steinfeld is looked at as secondary to Bridges and the Coen Brothers as the marketable stars of True Grit. Obviously the thinking isn’t entirely misguided (in terms of rooting out awards anyway) because both women got their deserved nominations. But just imagine the head scratching if Jennifer Lawrence had snared a Best Supporting Actress nomination for Winter’s Bone. Would it have been anything other than laughable? I hope that by the time the winner is announced in Lawrence’s category, Hailee Steinfeld has already had lots of time to smudge up her Oscar as the evening’s first triumphant Best Actress.There have been the usual suggestions that Oscars are as blind to the achievements of non-whites as ever, but in a year like this one that complaint raises the specter of quotas even more than it normally would. Who was it that won the Best Supporting Actress award last year, after all, in a movie that did not go wanting for recognition? The simple answer has to be that this year there just weren’t that many great roles for nonwhite actors of any race, and those ones that were great—Kerry Washington, Shareeka Epps, S. Epatha Merkerson and even Samuel L. Jackson in Mother and Child come to mind—came in films that were simply not on Oscar’s radar, for whatever race or non-race-based reason there might be. But even lodging these kinds of complaints regarding errors of omission, I took a look at the nominations in general this year and had to admit that, excepting one or two glaring instances, the list Oscar has come up with this year is a pretty solid one, at least as far as the major categories go. John Hawkes? Nice. Jeremy Renner? Nice. I wish Edgar Ramirez could be on the list, but okay, at least there’s some silly bylaw upon which that omission can be foisted.

I will say that I’m at a bit of as loss to explain the surge of love for Jacki Weaver, who plays the frighteningly ingratiating matriarch of an Australian family of murderous criminals in Animal Kingdom. Weaver is good with insinuating smiles and the contrast between honeyed pronouncements and sinister intentions, and with those gigantic eyes the intimidation factor certainly registers. But the part itself seems underwritten, and I must admit that, after months of hearing how dynamic and riveting was her performance, I kept waiting for the moment-- the moment—where the actress ensnared me in the evil machinations of her character and seduced me with her fearlessness as a performer. It never really came. I’m not saying I was looking for Melissa Leo, exactly, but if I’m thinking of ruthless criminal matriarchs “inspired by true events,” I’ll take Billie Whitelaw as Violet Kray, the spidery Freudian nightmare looking after Reggie and Ronnie (Gary and Martin Kemp) in Peter Medak’s superb historical crime drama The Krays.

And only two years in, and I’m ready to dump this whole 10 nominees for Best Picture experiment. Everyone knows it is designed largely so that the Academy can tell itself it’s more in touch with the vanguards of mass taste than it may actually be. So as a result big audience pictures like The Blind Side and Inception get their token nominations. But has anything like momentum for Inception, whose moment as an $880-million worldwide box-office hit has, to put it mildly, already come and gone, really changed? The vagaries of the Academy’s own system insured that Inception, despite its flurry of big-ticket nominations, would be an immediately also-ran when it failed to snag a Best Director nomination for Christopher Nolan. The consensus, and it seems undeniable, is that “they” just don’t like him and therefore manifested that dislike by voting for the Coen Brothers, against DGA precedent, instead of the Dream Warrior. The Hollywood Reporter, noting the snub, reported (in my favorite headline of the season) that “Christopher Nolan’s Snub Sparks Twitter Outrage,” but at that point even the deafening buzz of 880 million fanboys didn’t much matter a damn, and we were left to think about, in the framework of the friendlier, expanded Academy Award nomination format, whether or not Nolan might have actually deserved one. Listen, for all of that movie’s flaws I’d give Nolan a nomination over Darren Aronofsky or Danny Boyle in a beat of my heart. But over also-not-nominated directors like Lee Unkrich or Debra Granik? Probably not.

And only two years in, and I’m ready to dump this whole 10 nominees for Best Picture experiment. Everyone knows it is designed largely so that the Academy can tell itself it’s more in touch with the vanguards of mass taste than it may actually be. So as a result big audience pictures like The Blind Side and Inception get their token nominations. But has anything like momentum for Inception, whose moment as an $880-million worldwide box-office hit has, to put it mildly, already come and gone, really changed? The vagaries of the Academy’s own system insured that Inception, despite its flurry of big-ticket nominations, would be an immediately also-ran when it failed to snag a Best Director nomination for Christopher Nolan. The consensus, and it seems undeniable, is that “they” just don’t like him and therefore manifested that dislike by voting for the Coen Brothers, against DGA precedent, instead of the Dream Warrior. The Hollywood Reporter, noting the snub, reported (in my favorite headline of the season) that “Christopher Nolan’s Snub Sparks Twitter Outrage,” but at that point even the deafening buzz of 880 million fanboys didn’t much matter a damn, and we were left to think about, in the framework of the friendlier, expanded Academy Award nomination format, whether or not Nolan might have actually deserved one. Listen, for all of that movie’s flaws I’d give Nolan a nomination over Darren Aronofsky or Danny Boyle in a beat of my heart. But over also-not-nominated directors like Lee Unkrich or Debra Granik? Probably not. And I always get a kick out of listening to the harping on about the various technical awards snubs, because this is where I, as a former techie movie nerd of the first order, always used to get most of my dander up in the wake of the nominations announcement. I can remember scribbling furiously in a preamble to my annual Oscar ballot about the outrageous snub visited upon Rob Bottin and his effects crew when they were not acknowledged by Oscar for their work on The Thing. It didn’t matter to me that I would have never in a million years actually expected recognition for this box office flop, which in 1982 was dwarfed by the shadow of E.T.-- it was the principle of the thing! Nor did it matter to me that my no-doubt-brilliantly-articulated rage was being wasted on a ballot which would be read by precisely one other person who had any emotion invested in the Oscars at all. The rest of the Oscar pool participants that year could have cared less about awards and movies—they were in it for the fun of watching the TV show-- but by God it was my call to school ‘em, and school ‘em I would!

I was reminded of myself and my self-righteous screed when I saw this year’s list of nominees for Best Visual Effects-- Alice in Wonderland, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, Hereafter, Inception and Iron man 2. Solid technical achievements all and, with the possible exception of Alice, each and every one of them fairly routine in that they resemble the achievements of lots of other movies that have come down the pipe in recent years. My own nominee might have been the impish and playful effects that adorn (but are not the raison d’etre of) Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, or perhaps the skin-crawling, mythopoetic visualizations of Splice. But I can guarantee you there’s much more black feeling astir over the exclusion of the overwhelming effects in Tron Legacy than just about anything other Oscar omission this year. I got an e-mail from a friend earlier this week which expressed a lot of the frustration that people who saw and liked Tron Legacy (and yes, those people do exist) are feeling over the overlooking of this picture in the Visual Effects department. But what I thought was most amusing was the little reminder of the Academy’s attitude about the original Tron, again back in that watershed year of 1982 which had already given me such case for infuriation. The writer of the e-mail recalled that in 1982 there was no great love for Tron as a groundbreaking piece of special effects cinema. The original movie did get nods for Best Costume Design and Best Sound, and as is typical was recognized 14 years later with a special award for technical achievement once the movie’s influence on effects technology became undeniable. But according to Steven Lisberger, Tron’s writer-director, the movie was bypassed for Best Visual Effects consideration in1982 because “the Academy thought we cheated by using computers.” In other words, the landscape of the computer, not yet having taken over American life in every aspect, was still a no-man’s-landscape; if the effects didn’t exist in three-dimensional space, if they weren’t quantifiable, tactile, products of objects rendered on film, they weren’t real special effects.

In the time it took the Academy to catch up with Tron America caught up with it too, in terms of internalizing the very language that propelled the movie into the daily fabric of its collective life through the computer. So why the Academy brush-off this year? Could it be that, for all of its flash and wonder, Tron Legacy represented a world that has in its way become too familiar, too routine? Or maybe the movie was seen (properly, I’d say) as a lot of sound and thunder signifying nothing more than sensation, eschewing the fascinating allegorical framework that lay beneath the relative crudity of the first film. Okay, so if we accept any or all of that, the question remains: Why then the relatively dull effects that did get nominated?

Some final thoughts. I have to say that, in a banner year for documentaries in which Restrepo and Inside Job were nominated, it does tickle me that Banksy is nominated for Exit Through the Gift Shop, a movie that calls into question notions of art, the appreciation of art, and even the purposes and structure of the documentary film itself. Had there been room for The Tillman Story or Marwencol or even Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, this would have been the most flatly inarguable category of the year. How is it that the Best Song category, most usually a dumping ground for unmemorable caterwauling of every stripe in the post-Disney Animation Renaissance years, is this year populated by four nominees that actually seem to be good songs? And in that light, the most perversely underpopulated category of the year, Best Animated Film, is the one with the best argument for expansion. How annoying to be limited to only Toy Story 3, How to Train Your Dragon and The Illusionist when there was also Tangled, Despicable Me and My Dog Tulip from which to choose. Renaissance, indeed.

But enough about the Oscars. On to some friends I need to brag about. First, old pal Ali Arikan, he of Cerebral Mastication, The House Next Door, Roger Ebert. Com and many other shingles, has a new one to hang out—that of resident film critic for Dipnot.TV, a Turkish news site. The site is in Turkish, but that won’t keep me from heaping congratulations on a fellow well-deserving of his good fortune in this enterprise. Plans are afoot for expanding Ali’s influence within the Dipnot empire via an iPad magazine launch slated for February. Look for updates here, and in the meantime brush up on your Turkish and enjoy Ali’s work here, starting with a look back at the movies of 2010.

But enough about the Oscars. On to some friends I need to brag about. First, old pal Ali Arikan, he of Cerebral Mastication, The House Next Door, Roger Ebert. Com and many other shingles, has a new one to hang out—that of resident film critic for Dipnot.TV, a Turkish news site. The site is in Turkish, but that won’t keep me from heaping congratulations on a fellow well-deserving of his good fortune in this enterprise. Plans are afoot for expanding Ali’s influence within the Dipnot empire via an iPad magazine launch slated for February. Look for updates here, and in the meantime brush up on your Turkish and enjoy Ali’s work here, starting with a look back at the movies of 2010. Los Angelenos who enjoy the privilege of having a place like the New Beverly Cinema to aid them in their continuing cinematic education already know how lucky they are. But a little reminder never hurt, and this one comes from the inside, from the beating heart of the New Beverly itself. One of my favorite people, Julia Marchese, who happens to be special events coordinator and all-purpose muse for the theater, has a new blog called Flotsam and Jetsom and it is well worth a look. One of her first posts really separated the men/women from the boys/girls-- it's called "The First Rule Is, You Don't Talk About..." and it will answer many questions you didn't even know you had about why a young woman would decide she wanted to-- Well, I'll just let you read it and be surprised. Less outre but more emotionally charged is Julia's account of how her life became entwined with the New Beverly. She relates her own budding cinephilia marvelously here, but it's her relationship with the theater, and specifically with the theater's late owner-operator Sherman Torgan, which locates the soul in this cinema and illustrates just why this place means so much to so many. It's a beautiful and moving piece, and I hope Julia follows the blogging muse whereever it leads her. These two entries alone indicate that there's something special on the horizon if she does, for her and for us.

Los Angelenos who enjoy the privilege of having a place like the New Beverly Cinema to aid them in their continuing cinematic education already know how lucky they are. But a little reminder never hurt, and this one comes from the inside, from the beating heart of the New Beverly itself. One of my favorite people, Julia Marchese, who happens to be special events coordinator and all-purpose muse for the theater, has a new blog called Flotsam and Jetsom and it is well worth a look. One of her first posts really separated the men/women from the boys/girls-- it's called "The First Rule Is, You Don't Talk About..." and it will answer many questions you didn't even know you had about why a young woman would decide she wanted to-- Well, I'll just let you read it and be surprised. Less outre but more emotionally charged is Julia's account of how her life became entwined with the New Beverly. She relates her own budding cinephilia marvelously here, but it's her relationship with the theater, and specifically with the theater's late owner-operator Sherman Torgan, which locates the soul in this cinema and illustrates just why this place means so much to so many. It's a beautiful and moving piece, and I hope Julia follows the blogging muse whereever it leads her. These two entries alone indicate that there's something special on the horizon if she does, for her and for us. The Los Angeles division of the Horror Dads (me, Richard Harland Smith, Paul Gaita and Nicholas McCarthy—Jeff Allard and Greg Ferrara are East Coasters) finally got together a couple of weeks ago for a lunchtime summit at The Oinkster and it truly was a great, relaxing time. It was a genuine treat to spend time with these guys—none of whom I’d ever met in 3-D before—though I will say it’s been a good long while since I’ve spent time talking with guys who have so much joyful knowledge about genre cinema—particularly European horror of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. I felt completely out of their league in this regard, but they were to a man such genuinely friendly and entertaining folks that I can’t wait to get together, have a cheeseburger and be happily intimidated all over again. Of course, love of the movies, and love of our kids binds us all, and there was plenty to talk about on that front.

And Nicholas—who it turns out I had actually met before, in the aftermath of one of those giddy nights last summer at the New Beverly—is off at Sundance right now with a short film this year. It’s called The Pact, and it just last night completed its run there screening in front of a film entitled The Oregonian. You can see the trailer for the film here. I finally got a chance to see it myself a few nights ago and I was extremely excited for not only the film itself but what it bodes for Nicholas’s abilities as a stylist and a storyteller.

A terrific film that clocks in at 11 minutes is a film that wisely makes use of ambience, mood, the tension between what is seen and spoken of and what is implied, and the surety of the director’s hand in guiding the viewer to settle into the limited, haunted worldview of the main character. Nicholas’s movie is adept at all these things, anchored as it is in a beautifully modulated performance by Jewel Staite as a woman forced to oversee the estate of her recently deceased mother who comes to believe that her mother’s spirit, and the horrors of an abusive past, may not be content to remain consigned to death. What’s thrilling about The Pact is how it quite literally leaves you wanting more, speculating about inconsistent electrical signals in a darkened hallway and the empty spaces beckoning behind a basement door, all the while guiding the viewer by the gently insinuating pull of the camera (Did I just see something, or was it literally a trick of the light?) and our mutually shared desire for a spine-chilling touch, a signal that we will never be alone, whether we want to be or not. The Pact is a masterful little jewel of a short film, perfect if not for the necessary bit of exposition that anchors the film a little too literally before Nicholas’s camera and teasing sense of delayed gratification as a director sends it soaring. One hopes that the movie will soon become widely available and that further glory at Sundance will be forthcoming. For The Pact’s appreciative audience, the greatest tease now is not what fear lies waiting in that basement, but instead what Nicholas McCarthy will do for an encore.

Another short film definitely worth a look is Oren Shai’s Condemned, a creepily contemplative ode to the women-in-prison pictures of the ‘50s (perhaps most notably John Crowell’s Caged) which finds its unlikely pitch somewhere between Jack Hill and Rainer Werner Fassbender. Prisoner #1031 (Margaret Anne Florence) fearfully awaits execution within the confines of her dank cell, accompanied only by the occasional visits of a sneering guard and the Morricone-esque whistling that resides in her head, calling her to an alternate future that she will never access. Enter a sultry, Audrey Totter-inflected prisoner who shares #1031’s last hours and who may be an angel of death in waiting, and Shai’s recipe for low-boiling tension, conjured almost exclusively by the poker-faced terror of his heroine and the way her face is framed by the negative space and rusty accoutrements of a lonely, darkened cell, reaches its visual apex. Shai’s achievement, like McCarthy’s, is one of patience with building mood and ambience that is possible only when a director gets a handle of how to modulate little things like time and space, making our anticipation of the gathering of bits of information in such prescribed worlds as prison cells and haunted apartments of the utmost importance. And like The Pact, Condemned is a lovely illustration of the possibilities inherent in investigating genre forms when the director has something other than shock effects on his mind. (Click here and see Condemned for yourself.)

Finally, for those of you who can’t get enough Chucky—and frankly, I’ve developed quite an addiction myself these days—a couple of items worth passing on. First, there is the revelation culled from Oprah Winfrey’s interview with Piers Morgan that the 1998 box-office failure of Beloved, the movie which the star produced from Toni Morrison’s book that was directed by Jonathan Demme—was the biggest disaster of her professional life. “I don't want to call it a turkey, but it didn't work,” says the none-too-understated mogul, “and it sent me into a massive, depressive macaroni and cheese-eating tailspin. Literally!" But who does she blame for the movie’s failure to lure the public out to the movie theater to see her genuinely odd, tonally miscalculated movie? Herself? Touchstone Pictures? Thandie Newton? No, it’s Chucky’s fault, of course! Bride of Chucky, specifically, which had the audacity to come out the same weekend as Oprah’s medicinal motion picture and lay waste to its misconceived ass, providing what Oprah’s bitter, hardly little pill refused to provide—actual entertainment value to go along with its apparently demonically possessed characters. “It premiered on a Friday night and I remember hearing on Saturday morning that we got beat by something called Chucky,” bemoaned the TV titan. “I didn't even know what Chucky was," she asked viewers to believe (no doubt just before going on to tell a story about how she was awakened by a phone call on a Tuesday morning back in 1986 with news of her Oscar nomination, which she had no idea was even being announced that day!) The upside: the perpetually upbeat media giant’s first real inkling of what it means to be down in the dumps. “Oh, this is what it must feel like to be depressed,” she recalled saying to herself before remembering that she was the obscenely rich and powerful Oprah Winfrey. No word at whose feet she placed the artistic failure of Beloved…

And if you’re a Chucky fan in the Bay Area come Saturday, February 12, there’s going to be an event taking place which you will not want to miss. Renowned director/transgender performance artist Peaches Christ has a very special Valentine’s Day weekend on tap at the Victoria Theater-- ”When Chucky Meets Christ: A Monster-Sized Chucky Tribute”, presented in conjunction with the San Francisco Bay Guardian, SF Indiefest and Peaches Christ productions. In addition to a screening of Seed of Chucky, this special event will include an on-stage conversation between Peaches, the film’s star Jennifer Tilly and writer-director Don Mancini, a specially choreographed musical number and a killer costume contest. The fun begins at 8:00 p.m.. For more details you can access the Peaches Christ Web site. And if that doesn’t do ya, take a gander at this:

Here’s hoping that I can scrape together enough cash for a cheap Southwest Airlines flight to San Francisco, because if I can I’ll be there for this one. Sounds like the only thing that could possibly top our own Seed of Chucky tribute last October! At any rate, many congratulations to Don Mancini, whose cursed creation deserves all the recognition and extended life it can muster. All this will help me keep my own hopes alive that the adventures of Chucky will not have concluded with Seed, but that a new and vital chapter in this most subtly satiric and bedrock scary franchise might be just around the corner…

Speaking of coming soon… the year-end wrap-up posts this week. Watch for it!

***********************************************