SAW III

By the time the curtain rings down and the charnel house door swings shut on Saw III, the grisly series, which began life as a micro-budget calling card for screenwriter/star Leigh Whannell and director James Wan, completes the journey from one-off fluke hit to a genuine phenomenon that gains considerable power from its insistence on revisiting and expanding its own narrative history.

When the 2004 film blew up the box office and made back anywhere from 50 to 60 times its cost, it was clear that these two professed horror geeks would have to bow before the sequel gods and serve up another slice (or laceration, or tear, or whatever). But where the template for expanding successful horror franchises was pretty well set by the mindless repetition of the Friday the 13th series, or the inventive but inconsistent pattern of the Nightmare on Elm Street films, the second Saw film took a different tack. Instead of simply revisiting the two-men-in-a-room/detective investigation trajectory of the first movie, Saw II alternated a haunted house setting, complete with a new series of grisly scenarios to be survived (or not) by those trapped inside, with a riveting standoff between the villainous mastermind Jigsaw (Tobin Bell) and the crooked cop (Donnie Wahlberg) who is far more central to the movie’s machinations than we understand at first.

Saw II delivered the grisly goods for the mass audience to the tune of $85 million (making it the most profitable film of 2005), but it was satisfying to more sophisticated fans of the horror genre too because it made the most of the opportunity to fold back onto the first movie, fill in a few (glaring) holes of plot logic, and most importantly (and subversively) expand the weird game both movies play with the audience in asking/daring/demanding that we consider Jigsaw's murderously moralistic philosophy seriously on some level. It is very unusual to see a movie openly acknowledge any kind of sympathy with the perpetrator of horrific crimes against persons such as the ones we witness in Saw II, much less allow us to accept such brutalization as having any kind of moral underpinning. It’s much easier to just let the audience go along with their vicarious enjoyment of the cleverness that characterizes the violence without implicating them in it in any way. But that, along with giving its audience a filthy, unnerving good time, is precisely what Saw II reveals itself to be up to. If we can, on any level, understand Jigsaw’s rationale, however clouded by madness and helpless rage at his own fatal trajectory it may be (the man is riddled with cancer), then we are implicated in what we are seeing and forced to engage with the movie on a more potent level. Saw II set itself apart, in fundamental ways, from the structure of the first movie, and set us up in a most tantalizing way for part three.

And it is a pleasure to report that screenwriter Leigh Whannell and director Darren Lynn Bousman, well aware of the temptation to amp up the violence to the exclusion of all else, have fulfilled the potential of Saw II by creating, with Saw III, not a perfunctory sequel but a superior piece of shock entertainment that takes the series off into yet another narrative direction while expanding on the second film’s impulses to enrich the back story of Jigsaw (Tobin Bell) and his demented, self-loathing assistant Amanda (Shawnee Smith). Saw III serves up two intriguing new storylines—a young doctor (Bahar Soomekh) is kidnapped and forced to operate on the rapidly deteriorating Jigsaw, while in a parallel thread a father (Angus MacFadyen), destroyed by grief over the loss of his son, is turned loose on what will come to pass as Jigsaw’s final series of gruesome, agonizing tests—and teases out the connections between the two until we end up coming face to face with the inevitable trajectory of Jigsaw’s curious moral inquiry, one which finds the madman at the center of his own puzzle.

And it is a pleasure to report that screenwriter Leigh Whannell and director Darren Lynn Bousman, well aware of the temptation to amp up the violence to the exclusion of all else, have fulfilled the potential of Saw II by creating, with Saw III, not a perfunctory sequel but a superior piece of shock entertainment that takes the series off into yet another narrative direction while expanding on the second film’s impulses to enrich the back story of Jigsaw (Tobin Bell) and his demented, self-loathing assistant Amanda (Shawnee Smith). Saw III serves up two intriguing new storylines—a young doctor (Bahar Soomekh) is kidnapped and forced to operate on the rapidly deteriorating Jigsaw, while in a parallel thread a father (Angus MacFadyen), destroyed by grief over the loss of his son, is turned loose on what will come to pass as Jigsaw’s final series of gruesome, agonizing tests—and teases out the connections between the two until we end up coming face to face with the inevitable trajectory of Jigsaw’s curious moral inquiry, one which finds the madman at the center of his own puzzle. Saw III completes the journey begun in the 2004 film with satisfying finality, and with an agonizing awareness of a perpetual nightmare that, for once, is not rooted solely in the desire for the studio to make more and increasingly pointless sequels. The shocks that await attentive viewers at the end of Saw III are perhaps the series’ most devastating, because they are secured in the story of Jigsaw and Amanda, whose ultimate fates illuminate the movie’s thematic concerns—how we stand up to and ward off our worst impulses and thirst for vengeance—with a clarity and immediacy rare for the genre. I’d go so far to say that, taken as a whole, and given that I didn’t much care for the first Saw, the three films form a legitimate trilogy that can stand with the first three Alien films in terms of how each consecutive film informed the others while carving out unique narrative and/or stylistic territory with each new entry.

Darren Lynn Bousman directs Angus MacFadyen on the Toronto set of Saw III

Darren Lynn Bousman directs Angus MacFadyen on the Toronto set of Saw IIIThe Saw films are stylistically similar, as were the Alien films, of course-- the Alien films were all informed by the consistency of the H.R, Giger-inspired creatures and the overall art design. But the tone and approach differed from film to film, from Ridley Scott's cool malaise to James Cameron's muscular war imagery to David Fincher's oppressive close-ups and grim religious visual motifs, much as the narrative strategies of the Saw are as varied as the visual style is similar from film to film. I’d argue that the introduction of Bousman to the Saw series brought a directorial assurance and deftness of vision that the first film lacked. But the films are very different from each other in terms of what they serve up to the audience in terms of the way their stories are told and the direction those stories take. There’s a very satisfying sensibility at work here that honors the pact between storytellers and their audience that says more of the same is not enough. It’s a compliment of the highest order to say that, in retrospect, the Saw films don’t feel like an opportunistic, market-centric response to the fact that the first film was such a monster hit. I’ve spent the last couple of days since seeing Saw III reflecting on how all three films work together and seem like one long, well-observed, horrifying story told over the course of three films, a gorefest trilogy spun from, of all things, a confrontation with a very grim morality. Saw III folds back on both previous films in the same way Saw II did, filling in more holes, as well as expanding the characters of Jigsaw and Amanda in intriguing ways that leads to a very satisfying conclusion where the confrontation with Jigsaw's philosophy, his real purpose, moves front and center, right alongside with the series' most agonizing and gruesome set pieces, of course.

I was a little dismayed at first because the movie kicks off, in typical fashion, with a couple of grotesque traps, one of which dispatches the only other actor besides Bell and Smith to have appeared in all three Saw films, and neither of which looked very escapable to these eyes. More importantly, they seemed peripheral in importance to the ultimate thrust of the movie and seemed to violate the rules set down by Jigsaw—that those ensnared in the traps are given a legitimate chance to save themselves, depending on whether they have the intestinal fortitude and/or threshold of pain and/or escalating level of panic and madness necessary to emerge from them alive. That made me worry for a moment that what Bousman, Whannell and company had done was trade in any real thought behind these Rube Goldberg death scenarios in favor of the inevitable can-you-top-this? sensibility. The craven disregard of the pointless sequel seemed to be calling-- if the traps can't be beat, then that's a betrayal of the twisted reasoning behind them-- the test to see how much remaining alive means to the person hung up in all the gear. But, happily enough, Saw III is sufficiently clever that it even incorporates the kind of doubting observation that was nagging at me early on into the main course of the character action at the end—the fact that those traps weren’t challenges but jerry-rigged coffins turns out to be a central element in the fate of one of the film’s characters.

I was a little dismayed at first because the movie kicks off, in typical fashion, with a couple of grotesque traps, one of which dispatches the only other actor besides Bell and Smith to have appeared in all three Saw films, and neither of which looked very escapable to these eyes. More importantly, they seemed peripheral in importance to the ultimate thrust of the movie and seemed to violate the rules set down by Jigsaw—that those ensnared in the traps are given a legitimate chance to save themselves, depending on whether they have the intestinal fortitude and/or threshold of pain and/or escalating level of panic and madness necessary to emerge from them alive. That made me worry for a moment that what Bousman, Whannell and company had done was trade in any real thought behind these Rube Goldberg death scenarios in favor of the inevitable can-you-top-this? sensibility. The craven disregard of the pointless sequel seemed to be calling-- if the traps can't be beat, then that's a betrayal of the twisted reasoning behind them-- the test to see how much remaining alive means to the person hung up in all the gear. But, happily enough, Saw III is sufficiently clever that it even incorporates the kind of doubting observation that was nagging at me early on into the main course of the character action at the end—the fact that those traps weren’t challenges but jerry-rigged coffins turns out to be a central element in the fate of one of the film’s characters.(Speaking of happy, let’s not pretend that part of the appeal for anyone who appreciates the Saw films aren't those nasty traps. And Saw III features my favorite of the entire series—a possibly corrupt judge who is chained to the bottom of a large vat by a thick neck brace must rely on that previously mentioned tortured father, the human rat in Jigsaw’s maze, to free him before he drowns in a rising pool of offal pouring into the chamber, created by the liquefying of an endless production line of rotting, maggot-infested hogs dropped into a gauntlet of rotating saw blades. For a series condemned in some circles as witless, that’s pretty funny.)

Another way that Saw II upped the ante from the first film (and for horror franchises in general, I think) was in the quality of the acting, and Saw III is, if anything, even better performed across the board than II. MacFadyen and Soomekh, the series newbies, are effective as the father and the doctor, respectively, both tortured by home lives that have sent them spiraling into various levels of depression and despair, agonies Jigsaw claims to be guiding them through with his special kind of tough love. And the ultimate fate of Donnie Wahlberg, who ended up in that dank, smelly bathroom at the end of II, is explicated as well, giving us another chance to remember how good he was in the previous film. But Saw III ultimately belongs to two actors-- Tobin Bell is exceptional once again, even though the movie keeps him completely bedridden, except for some brief flashbacks. Amazing is a word that is bandied about with as much abandon as “masterpiece” or “awesome” these days, but it really is fairly amazing what Bell can do, the moral authority he manages to project, with practically no variance in his tone, facial expression and pace of line delivery. He’s fashioned a warped villainy that presides over three memorable horror films from an almost entirely sedentary performance, which Bousman’s overactive, occasionally overwrought camerawork and editing more than make up for, and it’s telling that, for all the gruesome sights and sounds indulged in over the course of this series, his heavy-lidded visage may be, along with that famous headgear shot featuring Smith from the first movie, the Saw franchise’s most potent image.

Another way that Saw II upped the ante from the first film (and for horror franchises in general, I think) was in the quality of the acting, and Saw III is, if anything, even better performed across the board than II. MacFadyen and Soomekh, the series newbies, are effective as the father and the doctor, respectively, both tortured by home lives that have sent them spiraling into various levels of depression and despair, agonies Jigsaw claims to be guiding them through with his special kind of tough love. And the ultimate fate of Donnie Wahlberg, who ended up in that dank, smelly bathroom at the end of II, is explicated as well, giving us another chance to remember how good he was in the previous film. But Saw III ultimately belongs to two actors-- Tobin Bell is exceptional once again, even though the movie keeps him completely bedridden, except for some brief flashbacks. Amazing is a word that is bandied about with as much abandon as “masterpiece” or “awesome” these days, but it really is fairly amazing what Bell can do, the moral authority he manages to project, with practically no variance in his tone, facial expression and pace of line delivery. He’s fashioned a warped villainy that presides over three memorable horror films from an almost entirely sedentary performance, which Bousman’s overactive, occasionally overwrought camerawork and editing more than make up for, and it’s telling that, for all the gruesome sights and sounds indulged in over the course of this series, his heavy-lidded visage may be, along with that famous headgear shot featuring Smith from the first movie, the Saw franchise’s most potent image. As for Smith, this movie really is her reward for enduring the horrors of parts one and two with little fanfare or recognition. As Amanda, she travels an arc from horrified victim to a survivor unconvinced she deserved to survive, to a madman's surrogate daughter who is also in love with Daddy, a damaged woman who may be the most gnarled-up and demented character of the three films. The exciting thing about Saw III, in terms of this character, is that we get to see all of these aspects of Amanda because of the way the movie is structured to expand upon what we’ve seen before-- it makes quite a show of revealing to what extent Amanda was involved in this carnival of horrors even from the beginning. Smith grabs onto these scenes with her teeth and shakes them for all they're worth—she gives a fearless performance, and I hope someone talks a little bit about her this time around. She’s no longer the narrative secret the Saw films have to keep hidden, and she exults in the chance to embody one of the more interesting characters I’ve seen in a horror movie in a long while.

As for Smith, this movie really is her reward for enduring the horrors of parts one and two with little fanfare or recognition. As Amanda, she travels an arc from horrified victim to a survivor unconvinced she deserved to survive, to a madman's surrogate daughter who is also in love with Daddy, a damaged woman who may be the most gnarled-up and demented character of the three films. The exciting thing about Saw III, in terms of this character, is that we get to see all of these aspects of Amanda because of the way the movie is structured to expand upon what we’ve seen before-- it makes quite a show of revealing to what extent Amanda was involved in this carnival of horrors even from the beginning. Smith grabs onto these scenes with her teeth and shakes them for all they're worth—she gives a fearless performance, and I hope someone talks a little bit about her this time around. She’s no longer the narrative secret the Saw films have to keep hidden, and she exults in the chance to embody one of the more interesting characters I’ve seen in a horror movie in a long while.Time magazine greeted the arrival of Saw III this week by talking about it in relation to other films, like Hostel, Wolf Creek, High Tension and the recent remakes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes, going so far as to dub the directors of these films “the Splat Pack.” So be it. But if nothing else (and, obviously, I think there's plenty else), Saw III exposes the empty shenanigans of a movie like Hostel to those who like their grue delivered on schedule but who also may be in their seats hoping for something to contextualize or enrich the bloody mayhem. Hostel’s most effective section was the 45 minutes leading up to the torture, which director Eli Roth exploited for all the queasy dread he could. But once we plop down inside that abattoir and realize that the movie has nowhere to go except for escalating the gore and becoming otherwise increasingly nonsensical, the hot air escapes out of Roth’s movie faster than a hitchhiking American tourist trying to skip out on the bill for his lodgings. Saw III, on the other hand, executes the steps in its bloody dance of death on the foundation of the audience’s fascination with its singular villain’s raison d’etre and with Amanda’s increasingly desperate need to connect with Jigsaw in order to avoid the looming realization that her life has no meaning beyond him.

The movie has the conviction of its actors, and of its own grim worldview, and it turns out to be, as well as a (literally) ripping good finale to a queasily interesting horror franchise, a twisted moral puzzle and a perverse love story based on the conviction that the best and worst impulses of people are practically indistinguishable and will both fail them in almost exactly the same way. Saw III comes to its end brutally, logically, with an icy exhilaration, a finish that should mark the terminus of the series as well. Will its creators be able to stave off the seductive promises of the shameless sequel?

3 comments:

It's really interesting to see someone tackle these films with such thoughtful consideration. I haven't actually seen any of them, and your piece here has done more to intrigue me than any of the trailers.

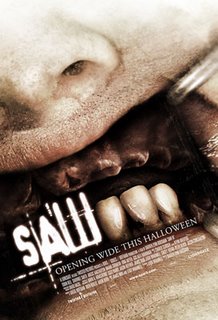

I dunno...I'm going to have to work hard to keep an open mind and go see SAW III, a film with the most revolting ad campaign I've seen in awhile...it's hard not to decide in advance that you're giving it too much credit. However, in this day of U.S. government-sanctioned torture, I have to allow for the possibility that a thoughtful horror film, with a serial killer with a conscience, might at least be worth a look. Is it possible this is a thinking person's horror franchise? I'd like to hope so. If not, I can always blame you...but of course, I won't. For one thing, the smug, smart-ass reviews I've read remind me how easy it is for critics to be dismissive of people who have actually created something. It's especially galling when the critics don't write half as well as you do...so off I go into the unknown!

Well, I have to admit, gentlemen, that the majority of reviewers that talked about Saw III all seemed to find it unredeeming and/or unendurable, so I can't call upon a whole lot of concurring opinion. But I was heartened to read today that Scott Foundas seemed to think that there was something worthwhile going on in that torture chamber as well. Not that I'm necessarily looking for validation, but it was starting to seem a little cold out there!

Post a Comment