OPENING SHOTS: FEMME FATALE AND YOJIMBO

Jim Emerson is a very busy man over at Scanners these days. In addition to filling in reviews at RogerEbert.com while Ebert continues recuperating from cancer surgery, he’s maintaining a very entertaining and fascinating environment on his own blog. Click the link above and you’ll get in on some very interesting discussions about the marketing of a certain reptilian aviation thriller coming soon to a theater near you; Sasha Baron Cohen’s Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan;

Jim Emerson is a very busy man over at Scanners these days. In addition to filling in reviews at RogerEbert.com while Ebert continues recuperating from cancer surgery, he’s maintaining a very entertaining and fascinating environment on his own blog. Click the link above and you’ll get in on some very interesting discussions about the marketing of a certain reptilian aviation thriller coming soon to a theater near you; Sasha Baron Cohen’s Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan; the debate over how politicized Oliver Stone’s new film World Trade Center really is; and enough good stuff on the smashing new horror film The Descent to make you want to see it again right away.

the debate over how politicized Oliver Stone’s new film World Trade Center really is; and enough good stuff on the smashing new horror film The Descent to make you want to see it again right away.(Warning: if you haven’t yet seen The Descent, you must get yourself to a theater near you and MUST NOT READ THESE until you do.)

But, as juicy as Scanners has been lately, the Opening Shots project continues as well. Jim claims to have a whole bunch more yet to publish, so keep your eyes open. Just in the last couple of weeks he’s highlighted the following:

Tom Sutpen of If Charlie Parker Were a Gunslinger… on Richard Lester’s Petulia;

Sam Goldsmith and Jerry Matthews on Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night;

Edward Bowie on Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark;

Jeff Levin on Philip Kaufman’s Quills;

Nathaniel Soltesz on Michael Tolkin’s The Rapture;

Robert Horton on Ivan Passer’s Cutter’s Way;

and Jim himself on Claude Chabrol’s La Femme Infidel, Ramin Bahrani’s Man Push Cart and HBO’s series The Wire.

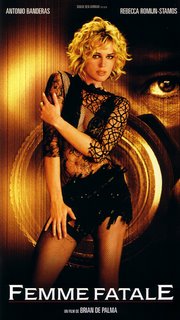

He also found space for a couple of my own submissions as well, taking a detailed look at the opening shots of Brian De Palma’s Femme Fatale and Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. (In the spirit of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Jim published my essay alongside that of Or Shkolnik, and you can read them side by side here.)

Upon seeing my Femme Fatale piece on Jim site, I realized that it ended up being merely a description of De Palma’s admittedly enthralling opening shot, and I think I became so enthralled in the literal translation that I left no room for any kind of analysis of what was really going on in the shot. Thankfully, Jim stepped in and did the heavy lifting for me here in a comment he posted immediately following my entry. Here then, with screen grabs cribbed from Jim’s site, is my description of the opening of Femme Fatale. If nothing else, you may be inspired to go rent it and watch the movie again, and after hearing what Jim has to say afterward you most surely will.

*************************************************************************************

Brian De Palma’s exceedingly stimulating and sensational consideration of femme fatale iconography and the possibility of redemption within it begins with one of the director’s customarily brilliant, multilayered opening shots.

Under the black of the producers credits, familiar voices are heard. It’s Fred MacMurray. Fade up on a shot of an extreme close-up of a TV. It’s MacMurray, 525 broadcast lines blown up to big-screen size, in "Double Indemnity". But a close examination of the image reveals a splash of color -- something else is visible here, contrasting with the black-and-white images of Billy Wilder’s film. It’s a reflected image of a half-naked woman stretched out perpendicular across the TV screen. She is watching "Double Indemnity", and we see her watching the movie in her reflection off the glass TV screen. "Double Indemnity" continues to play out, crosscutting between MacMurray and the original femme fatale, Barbara Stanwyck (as Phyllis Dietrichson).

The image of the young woman becomes clear, yet remains slightly ghostly, as the image in Wilder’s film darkens. MacMurray moves to close a window, when a shot rings out. Stanwyck has betrayed him with a bullet, and the title credit "Femme Fatale" pops on screen at the same time, as the ethereal image of the woman, reclining on her side, dispassionately watching the movie, lingers. (The title credit “A Film by Brian De Palma” was earlier synchronized with Stanwyck’s first appearance on the TV.) Now De Palma’s camera begins to pull back. We see the cabinet of the TV, and we can now also observe that there are French subtitles superimposed on Wilder’s film. The image of the woman reflected in the TV seems even clearer now, as we continue to pull back, seeing her much more clearly in the flesh, gray tendrils rising from the cigarette she’s smoking while watching the TV. At this point there is double layering of the woman’s image, the reflection and the person being reflected, over the image of Stanwyck, who has taken a dominant position over her wounded lover as she confesses her machinations against him.

The camera pulls all the way back to reveal that the woman watching is nude, her ass covered by a sheet, her bare back and legs exposed to us. Like the samurai in "Yojimbo", we’ve not had a clear look at her face, except for what we could discern in the reflection on the TV screen, and we’ll be denied one for the length of the shot. Suddenly a door opens (off screen), outside light briefly streams in and the door closes, as we hear a man’s voice say, “What the fuck are you doing?” A black man in a tuxedo enters the frame from the left and turns off the TV. The woman has not moved, not acknowledged his presence, not said a word. The camera begins moving in on him as he begins to quiz her. “Do you know what time it is?” She gets up off the bed, revealing that she is at least wearing black panties, but totally unselfconscious in this man’s presence in the fact that she is otherwise naked. She stands and moves across him to the left, still smoking. She begins to dress and he continues in what seems at first to be a parody of the hardboiled language we’ve just heard and seen on the TV:

The camera pulls all the way back to reveal that the woman watching is nude, her ass covered by a sheet, her bare back and legs exposed to us. Like the samurai in "Yojimbo", we’ve not had a clear look at her face, except for what we could discern in the reflection on the TV screen, and we’ll be denied one for the length of the shot. Suddenly a door opens (off screen), outside light briefly streams in and the door closes, as we hear a man’s voice say, “What the fuck are you doing?” A black man in a tuxedo enters the frame from the left and turns off the TV. The woman has not moved, not acknowledged his presence, not said a word. The camera begins moving in on him as he begins to quiz her. “Do you know what time it is?” She gets up off the bed, revealing that she is at least wearing black panties, but totally unselfconscious in this man’s presence in the fact that she is otherwise naked. She stands and moves across him to the left, still smoking. She begins to dress and he continues in what seems at first to be a parody of the hardboiled language we’ve just heard and seen on the TV:“Listen up. At 2200 Wetsuit’s down the hole when the snake hits the carpet. Security lifts the key. I terminate the torpedoes.”

The woman has now put on her top and moved completely out of frame to the left.

“Charm the snake into the stall. Bait and switch. At 2220 Wetsuit turns out the lights. Glasses on. I bag the snake.”

The camera is now pulling back as he moves left to where she is.

“Key in the bag. Bag to the boat. No radio unless absolutely necessary.”

The man has now seated himself next to the woman backward on a chair, as she continues to prepare herself at a vanity. She has still offered no response to what he is saying, or even really acknowledged his presence, or whether she is even hearing what he is saying or not. She tamps down her slick, short, dyed blonde hair with both hands, still holding a cigarette in the left.

“Code red, five minutes to blackout. Drop everything. Walk away. If the cops catch you, tell them the truth. You know no one. Got it?”

By now the man has begun staring at her intensely, looking for some hint that she is processing what he is saying to her.

“Got it?”

She leans into the frame, looks directly at him, coolly blows smoke in his direction, and nods.

“You have your passport?”

She flicks it into frame very casually. He peruses the document and continues:

“The plane leaves tomorrow at 0700.”

She flippantly offers a mock salute, as if to say, “Yes, sir, sir!” He smiles.

“And remember, no names and no guns.”

Suddenly there is the sound of a crowd chattering and milling about outside. The man acknowledges it with a cursory glance, but before we have had the chance to really process it ourselves, he leans forward slightly and slaps the woman hard across the face. She leans back, absorbs the blow and then slowly leans forward into a straight-up sitting position, her face still turned away from us and toward him, never taking her eye off of him. He continues:

“Are you high?”

She shakes her head slowly.

“Then stop dreaming, bitch. This isn’t a game tonight. People can die. Now get moving.”

He places the passport in his jacket pocket, rises up off the chair and moves away from her, toward the drawn curtain at the center of the room (and the frame). We become aware again of the sound of that mysterious crowd outside. He turns to her again, bends down out of frame and retrieves a headset, holds it up to her and says,

“You forget something?”

The woman emerges from the left, walks up to the man, never taking her eyes off his face, and grabs the headset from him. The producer’s credits are superimposed on the man as he rubs his hands together and considers this unflappable, impossibly cool woman. He adjusts his tie and his lapels, and light once again floods the room as the woman opens the door off screen. He turns sharply toward the window, reaches up and throws open the shade.

Cut to a long shot of the red carpet on closing night of the Cannes Film Festival. The credit is superimposed over the scene of the festivities: Directed by Brian De Palma.

JE: You picked a doozy here, Dennis! And there's so much communicated in this shot beyond the dialogue and the details of the caper, too. First, there's Double Indemnity -- the climactic scene of Double Indemnity, after MacMurray's plans have gone awry and he's wised up to what a sucker he's been -- with French subtitles. Well, the movie is called Femme Fatale, a French phrase, and now we assume we're probably in France. Visually, with that reflection/superimposition, De Palma transfers the title from Stanwyck to his "femme fatale" -- and, in movie terms, updates her in the process: She's still a blonde, but she's got a modern androgynous haircut... and she's nude, which is not something you would have seen in a 1944 Paramount Picture. (Also, something tells me this woman is not watching Double Indemnity for the first time; if anything, she's refreshing her study of it for her role in the movie we're about to see.)

JE: You picked a doozy here, Dennis! And there's so much communicated in this shot beyond the dialogue and the details of the caper, too. First, there's Double Indemnity -- the climactic scene of Double Indemnity, after MacMurray's plans have gone awry and he's wised up to what a sucker he's been -- with French subtitles. Well, the movie is called Femme Fatale, a French phrase, and now we assume we're probably in France. Visually, with that reflection/superimposition, De Palma transfers the title from Stanwyck to his "femme fatale" -- and, in movie terms, updates her in the process: She's still a blonde, but she's got a modern androgynous haircut... and she's nude, which is not something you would have seen in a 1944 Paramount Picture. (Also, something tells me this woman is not watching Double Indemnity for the first time; if anything, she's refreshing her study of it for her role in the movie we're about to see.)I love the way De Palma compartmentalizes screen space here, too, using frames within frames. (Remember, this is a guy who loves split screen: Sisters, Carrie...) First there's the TV screen (which is also a mirror), then the window that is obviously behind the drapes, and which will be used for the final reveal you describe. As you say, the journey is from a film (DI on TV) ... to a film festival (outside the window). De Palma keeps composing and re-composing -- and I think my favorite little moment is when she thrusts her head into the left edge of the frame (this profile is the closest we get to seeing her non-reflected face) to defiantly confront the man, coordinator of the unfolding plot, who is there to keep her in line. At the mirrored vanity, we have more frames-within-frames, but De Palma keeps us craning our necks to see more (kind of like Polanski's famous doorway shot of Ruth Gordon on the bedroom phone in Rosemary's Baby). He never actually shows us a clear reflection of the woman in those mirrors, frustrating our expectations. At the end of the shot we don't see her leave, but the light from an opened door (to the bathroom? hallway?) spills into the room. The movie's visual strategy has been beautifully set up now: We will be seeing pictures within pictures, one part of the whole but never the Big Picture... until the end of the picture.

This Jim Emerson guy is good!

*************************************************************************************

And finally, here’s my entry on Yojimbo (again, thanks to Jim for the screen grabs):

*************************************************************************************

The samurai films of Akira Kurosawa, themselves heavily influenced by the films of John Ford, were subject to reinterpretation several times themselves, the most famous examples being John Sturges’ refashioning of "Seven Samurai" into "The Magnificent Seven" and, more profoundly, Sergio Leone forging not only a remake, but the foundation of his entire directorial style, out of the discoveries he would make as he twisted new shapes into "A Fistful of Dollars" out of the original clay of Kurosawa’s "Yojimbo." Leone’s film follows Kurosawa’s template closely, but even by looking just at the opening shot it’s possible to see some of the parallels, and the differences, between Kurosawa and Leone.

The film begins on a close-up of a mountain range. A man, seen from behind and shot from a low angle, moves into the frame and observes the range which looms spectacularly before him. Leone might stage this shot to emphasize the landscape dwarfing his human figure by placing the figure low and small in the frame against the mountains. But Kurosawa achieves the same effect by giving the man roughly the same amount of graphic weight in the frame, but by shooting him from a low angle and keeping his face hidden from us. The man, dressed in the clothes of a samurai (the clothes themselves are ragged, worn and dirty), holds himself with dignity, adjusts his shoulders, and then, in a gesture that will find echoes throughout Leone (particularly in the opening of "Once Upon a Time in the West," reaches up under his robe and unceremoniously scratches his head—with a single scratch, the deflation of the image of this dignified samurai warrior is underway.

The film begins on a close-up of a mountain range. A man, seen from behind and shot from a low angle, moves into the frame and observes the range which looms spectacularly before him. Leone might stage this shot to emphasize the landscape dwarfing his human figure by placing the figure low and small in the frame against the mountains. But Kurosawa achieves the same effect by giving the man roughly the same amount of graphic weight in the frame, but by shooting him from a low angle and keeping his face hidden from us. The man, dressed in the clothes of a samurai (the clothes themselves are ragged, worn and dirty), holds himself with dignity, adjusts his shoulders, and then, in a gesture that will find echoes throughout Leone (particularly in the opening of "Once Upon a Time in the West," reaches up under his robe and unceremoniously scratches his head—with a single scratch, the deflation of the image of this dignified samurai warrior is underway.  The warrior looms in the frame, the mountain range but a background, and begins to move off to the left as the credits roll. We’re still seeing the man essentially only from behind, and he has now moved away from the mountain range, and Kurosawa still shoots him from that low angle—he is framed now only against the white, clouded sky of the afternoon. With the range now receded into absence, the man now seems to tower over his surroundings, greater than all he surveys—though nothing that he surveys is visible at this point in the shot. He looms large even as he moves deliberately along, adjusting his collar. Upon the appearance of the credit “produced and directed by Akira Kurosawa” the camera tilts down and we see the man’s raggedy sandals as he pads along on a dirt road—the landscape has been brought down to the level of this man moving silently through it. The visual strategy here is the inverse of close-ups and lone figures against the landscape that would mark Leone’s adaptation of "Yojimbo," and then eventually his entire style—in the opening of "Yojimbo", as the samurai moves along the road, the surrounding landscape dwarfs him by creating not a sense of its expansiveness, but instead of the claustrophobia created the tall grass alongside the road and the way the director angles the perspective on the man to exclude a sense of anything but the immediate space surrounding him.

The warrior looms in the frame, the mountain range but a background, and begins to move off to the left as the credits roll. We’re still seeing the man essentially only from behind, and he has now moved away from the mountain range, and Kurosawa still shoots him from that low angle—he is framed now only against the white, clouded sky of the afternoon. With the range now receded into absence, the man now seems to tower over his surroundings, greater than all he surveys—though nothing that he surveys is visible at this point in the shot. He looms large even as he moves deliberately along, adjusting his collar. Upon the appearance of the credit “produced and directed by Akira Kurosawa” the camera tilts down and we see the man’s raggedy sandals as he pads along on a dirt road—the landscape has been brought down to the level of this man moving silently through it. The visual strategy here is the inverse of close-ups and lone figures against the landscape that would mark Leone’s adaptation of "Yojimbo," and then eventually his entire style—in the opening of "Yojimbo", as the samurai moves along the road, the surrounding landscape dwarfs him by creating not a sense of its expansiveness, but instead of the claustrophobia created the tall grass alongside the road and the way the director angles the perspective on the man to exclude a sense of anything but the immediate space surrounding him.

The mountains have long since disappeared behind the tops of the grass as the samurai encounters some stone markers along the road and turns past them, as if to examine them. A series of title cards reads: “The time is 1860. The emergence of a middle class has brought about the end to power of the Tokugawa Dynasty.” The man’s observance of the markers is but a momentary distraction and he is soon heading back down the road. As he moves along, the mountain range returns to the top of the frame, only it too is dwarfed graphically by the expanse of grassy field the man finds himself moving through.

The mountains have long since disappeared behind the tops of the grass as the samurai encounters some stone markers along the road and turns past them, as if to examine them. A series of title cards reads: “The time is 1860. The emergence of a middle class has brought about the end to power of the Tokugawa Dynasty.” The man’s observance of the markers is but a momentary distraction and he is soon heading back down the road. As he moves along, the mountain range returns to the top of the frame, only it too is dwarfed graphically by the expanse of grassy field the man finds himself moving through.  More title cards: “A samurai, once a dedicated warrior in the employ of royalty, now finds himself with no master to serve other than his own will to survive… and no devices other than his wit and his sword.” The man has encountered a fork in the road, each trail leading he knows not where, and his preference of destination is nonexistent. His next move, like the momentary, alternating allegiances that he will assume later in the film, will be left to chance, as will his own fate. He takes in the surrounding space of the divided road, still surrounded by tall grass, and comes upon a large stick, which he picks up and tosses in the air. Where it lands will determine what direction he goes, what road he takes…

More title cards: “A samurai, once a dedicated warrior in the employ of royalty, now finds himself with no master to serve other than his own will to survive… and no devices other than his wit and his sword.” The man has encountered a fork in the road, each trail leading he knows not where, and his preference of destination is nonexistent. His next move, like the momentary, alternating allegiances that he will assume later in the film, will be left to chance, as will his own fate. He takes in the surrounding space of the divided road, still surrounded by tall grass, and comes upon a large stick, which he picks up and tosses in the air. Where it lands will determine what direction he goes, what road he takes…*************************************************************************************

The Scanners Opening Shots Project will continue for the foreseeable future. Keep an eye on Jim’s site for the next fascinating entries!

6 comments:

Hi Dennis--In case you hadn't seen it, I just wanted to point out that we bloggers popped up in the news over at De Palma A La Mod. [scroll down just a tad.]

Thanks for the tip, Girish. De Palma a la Mod is a terrific, all-encompassing site for De Palma fans and scholars-- we've hit the big time! And with the release of The Black Dahlia next month, this site should continue to be one to keep a close eye on.

All right, all right, I'll watch "Femme Fatale" again...and I'll have you to blame when i'm disappointed again.:) I am kind of looking forward to "The Black Dahlia." I haven't actually read this yet--too late at night--so I'll save it for after my viewing of "FF."

Romijn's dialogue contains a quote from "Double Indemnity" during the climactic scene on the bridge, in the second part of this line ... "I'm a bad girl, Nicholas. Rotten to the heart."

I loved this movie.

Ugh, The Descent was worthless, a wrote, trite, and worst, unfrightening horror movie. Who cares how many shots it steals fr . . . I mean pays homage to? I'm sure seeing it with the original ending would have redeemed the entire experience somewhat, though not by much.

I thought FF absolute dreck (Brian de Hairy-Palmas); only rented it for the Sakamoto score. Pitiful dialogue throughout, if one can yank his noggin' out of leather & lace-land.

Yojimbo, however, is unparalleled.

Post a Comment