I LOVE THE SMELL OF MIMEOGRAPH PAPER IN THE MORNING: Dennis Submits To The Van Helsing Quiz

1) What film made you angry, either while watching it or in thinking about it afterward?

Getting angry while watching a movie doesn’t seem too unusual. Casual missteps in direction, wrongheaded acting choices, dumb dialogue, all of these can lead to headaches, even if they occur in movies we otherwise like. Getting really fired up, really pissed off and flat-out offended, that’s a much less frequent occurrence (Cinema, my blood pressure thanks you). However, two of the instances I remember most vividly making me boil involved the manhandling, steamrolling or just plain out-and-out disregard for the subtleties and special qualities of children’s literature. I saw Walt Disney’s adaptation of Alice in Wonderland in college, after reacquainting myself with Lewis Carroll’s books, and was flabbergasted at how little care was taken to preserve the texure and rather somber disorientation that I found so fascinating in the read. Enough of the wordplay made it in to make the cartoon reconizable as being based on Carroll’s work, but then there were the songs wedged in to make it all “family friendly” that really shattered the illusion that the movie had anything to do with the book I loved. (Even more annoying was Disney’s abysmal marketing of the movie as yet another 2001/Fantasia head trip.) More recently, I was aghast at what Mike Meyers, director Bo Welch and screenwriters Alec Berg, David Mandel and Jeff Schaffer were allowed to do to Dr. Seuss’ much-revered fable The Cat in the Hat.

If there is such a thing as rape of literature, here is a prime instance of it. But the angriest I think I’ve ever been, practicaly from start to finish and for hours, days afterward, had to be when I saw Mississippi Burning. It’s not very often that subjects like the Civil Rights Movement get the big budget treatment. But when a movie like this is the result, it’s hard to argue with critics, pundits and Joe Average Ticketbuyer when they say (if they say) that Hollywood just doesn’t get it, or to not come to the conclusion that social issue dramas are better left to television, where the financial stakes aren't so high from project-to-project. It could have been big money influence, or it could have been the incredible arrogance of director Alan Parker and writer Chris Gerolmo that turned the true story of the murders of three civil rights workers into a hot-blooded B-movie revenge melodrama. Adding insult to injury, Parker and Gerolmo cast the FBI (which in real life took steps to hamper the investigation) as white (!) knights riding to the rescue, with head agent Gene Hackman finally losing his cool and going after the baddies with fictitious methods of torturous interrogation only after the white wife of a local deputy starts getting her clock cleaned by her hubby! And, of course, when Hackman’s bookish partner, Willem Dafoe, questions Hackman’s motivation and raises objections to these methods, Hackman shouts him down and puts him in his place. The movie is full of the usual Parker grotesqueries—lots of lovingly shot lynchings and shootings and beatings to linger over, all in the name of peace, love and understanding, slobbering redneck villains and saintly Negro victims (no African-American is allowed to live and breathe as a character in this movie), and the total disregard for anything, like consistency or believability of character, that doesn’t add up to an immediate, bludgeoning effect. Mississippi Burning purports to be about the evil results of hate, and in the end I ended up hating Alan Parker.

If there is such a thing as rape of literature, here is a prime instance of it. But the angriest I think I’ve ever been, practicaly from start to finish and for hours, days afterward, had to be when I saw Mississippi Burning. It’s not very often that subjects like the Civil Rights Movement get the big budget treatment. But when a movie like this is the result, it’s hard to argue with critics, pundits and Joe Average Ticketbuyer when they say (if they say) that Hollywood just doesn’t get it, or to not come to the conclusion that social issue dramas are better left to television, where the financial stakes aren't so high from project-to-project. It could have been big money influence, or it could have been the incredible arrogance of director Alan Parker and writer Chris Gerolmo that turned the true story of the murders of three civil rights workers into a hot-blooded B-movie revenge melodrama. Adding insult to injury, Parker and Gerolmo cast the FBI (which in real life took steps to hamper the investigation) as white (!) knights riding to the rescue, with head agent Gene Hackman finally losing his cool and going after the baddies with fictitious methods of torturous interrogation only after the white wife of a local deputy starts getting her clock cleaned by her hubby! And, of course, when Hackman’s bookish partner, Willem Dafoe, questions Hackman’s motivation and raises objections to these methods, Hackman shouts him down and puts him in his place. The movie is full of the usual Parker grotesqueries—lots of lovingly shot lynchings and shootings and beatings to linger over, all in the name of peace, love and understanding, slobbering redneck villains and saintly Negro victims (no African-American is allowed to live and breathe as a character in this movie), and the total disregard for anything, like consistency or believability of character, that doesn’t add up to an immediate, bludgeoning effect. Mississippi Burning purports to be about the evil results of hate, and in the end I ended up hating Alan Parker.2) Favorite sidekick

I love Walter Brennan, of course, most of all in Rio Bravo, but I’ll also give props to his Bizarro-world counterpart, who lived on SCTV after the show left NBC in 1982. It was on a parody of western serials called Six-Gun Justice that Don Mills (Eugene Levy) fought the black-hatted Slade Cantrell (Joe Flaherty) with a little help from a very Brennan-esque fella called Cheaplaffs Johnson (Martin Short)—this hilarious caricature was a highlight of the short-lived Cinemax episodes of SCTV. I’m also partial to Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street.

I love Walter Brennan, of course, most of all in Rio Bravo, but I’ll also give props to his Bizarro-world counterpart, who lived on SCTV after the show left NBC in 1982. It was on a parody of western serials called Six-Gun Justice that Don Mills (Eugene Levy) fought the black-hatted Slade Cantrell (Joe Flaherty) with a little help from a very Brennan-esque fella called Cheaplaffs Johnson (Martin Short)—this hilarious caricature was a highlight of the short-lived Cinemax episodes of SCTV. I’m also partial to Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street.3) One of your favorite movie lines

Professor Van Helsing, as they used to say about a beloved greasy potato chip, nobody can eat just one. And with the exception of one, you might say that right now I’m in the mood for a laugh…

“Refund? Refund?!” – Paul Dooley as Dennis Christopher’s beleagured papa in Breaking Away

”I'm sorry, sir. I was just pondering what drifter's corpse you stole those shoes from.” - Nathanial Mayweather (Chris Elliot), distractedly responding to the headmaster of Stephenwood Fancy-Lad Finishing School, from Cabin Boy

”I'm sorry, sir. I was just pondering what drifter's corpse you stole those shoes from.” - Nathanial Mayweather (Chris Elliot), distractedly responding to the headmaster of Stephenwood Fancy-Lad Finishing School, from Cabin BoyAfter being read the riot act by studio head Jack Woltz (John Marley) about why Johnny Fontaine will never get that picture, Tom Hagen quietly replaces his napkin and silverware and stands up: “Thank you for the dinner and a very pleasant evening. If your car could take me to the airport. Mr. Corleone is a man who insists on hearing bad news immediately.” Next stop: Khartoum in the bedroom (The Godfather)

“They call Los Angeles the City of Angels. I didn’t find it to be that exactly, but I’ll allow as there are some nice folks there. Course, I can’t say I seen London, and I never been to France, and I ain’t never seen no queen in her damn undies, as the fella says. But I’ll tell you what—after seeing Los Angeles and this here story I’m about to unfold—well, I guess I seen somethin’ every bit as stupefyin’ as you’d see in any of those other places, and in English too, so I can die with a smile on my face without feelin’ like the Good Lord gypped me.”-- The Stranger (Sam Elliot), The Big Lebowski

“They call Los Angeles the City of Angels. I didn’t find it to be that exactly, but I’ll allow as there are some nice folks there. Course, I can’t say I seen London, and I never been to France, and I ain’t never seen no queen in her damn undies, as the fella says. But I’ll tell you what—after seeing Los Angeles and this here story I’m about to unfold—well, I guess I seen somethin’ every bit as stupefyin’ as you’d see in any of those other places, and in English too, so I can die with a smile on my face without feelin’ like the Good Lord gypped me.”-- The Stranger (Sam Elliot), The Big Lebowski “I was Lon Chaney’s lover!” – Johnny Knoxville, in mock outrage (and bad old-age makeup), to the night manager after being tossed from a Hollywood convenience store for obvious and relentless shoplifting, from jackass: the movie

“I was Lon Chaney’s lover!” – Johnny Knoxville, in mock outrage (and bad old-age makeup), to the night manager after being tossed from a Hollywood convenience store for obvious and relentless shoplifting, from jackass: the movieAnd finally, this perfectly nonsensical exchange from Horsefeathers-- Professor Wagstaff (Groucho) is “teaching” a class, and Baravelli (Chico) decides to engage the prof in a little back-and-forth:

Wagstaff: As you know, there is constant warfare between the red and white corpuscles. Now then, baboons, what is a corpuscle?

Baravelli: That's easy. First there's a captain. Then there's a lieutenant. Then there's a corpuscle.

Baravelli: That's easy. First there's a captain. Then there's a lieutenant. Then there's a corpuscle.Wagstaff: That's fine. Why don't you bore a hole in yourself and let the sap run out? We now find ourselves among the Alps. The Alps are a very simple people living on a diet of rice and old shoes. Beyond the Alps lies more Alps, and the Lord Alps those that Alps themselves. We then come to the bloodstream. The blood rushes from the head down to the feet, gets a look at those feet, and rushes back to the head again. This is known as auction pinochle. Now in studying your basic metabolism, we first listen to your heartsbeat. And if your hearts beat anything but diamonds and clubs, it's because your partner is cheating - or your wife...Now take this point for instance (He points to a horse's ass placed over an anatomy chart - a picture of Pinky's beloved horse that he placed there when Wagstaff wasn't looking) That reminds me, I haven't seen my son all day. Well, the human body takes many strange forms. Now here is a most unusual organ. The organ will play a solo immediately after the feature picture. Scientists make these deductions by examining a rat, or your landlord, who won't cut the rent. And what do they find? Asparagus! Now, on closer examination-- (Pinky—played by Harpo-- has now placed a picture of his ballerina beauty over Wagstaff's anatomy chart) Hmm! This needs closer examination. In fact, it needs a nightgown. Baravelli, who's responsible for this? Is this your picture?

Baravelli: I no think so. It doesn't look like me.

(Thanks to Matt Zoller Seitz for pointing me toward FilmSite, which saved me from having to transcribe this entire bit from my DVD by hand.)

4) William Holden or Burt Lancaster?

4) William Holden or Burt Lancaster?I acknowledge Burt Lancaster’s versatility, likability and talent as an athlete, actor and producer (and I acknowledge that “mesmerizing torso” too); I appreciate his Moonlight Graham as literally the only thing I found tolerable about Field of Dreams; I love The Crimson Pirate, The Killers and Sweet Smell of Success (though not Elmer Gantry); and I am forever grateful for his Ned Buntline in Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians… and his Felix Happer in Local Hero. But William Holden was in, and was integral to the artistic success of, Sunset Boulevard, The Bridge on the River Kwai and The Wild Bunch, and he was excellent even when saddled with the voice of moral authority in Chafesky and Lumet’s Network. Holden gets my vote.

5) Describe a perfect moment in a movie

A blind young man, who plays piano for a girls’ dance school in Rome where a couple of grisly murders have already occurred, is fired after his seeing-eye dog attacks a child at the school. He storms out of the building and, after getting drunk at a pub, begins to make his way home, accompanied by the accused animal. As he makes his way down the street, the camera tracks along with him and a familiar, insistent and haunting theme begins to ring ominously on the soundtrack. The blind man continues his walk through the empty streets, the soundtrack begins to work its dreadful magic, and that awful feeling begins to set in—surely, after that unpleasant scene with the school headmistress that precipitated the firing, a scene played out in front of several students, this man is being set up to be the vicious killer’s next victim. But despite that feeling, the camera subtly reinforces the notion that, though it is dark and the man is alone, there is nothing particularly threatening about his surroundings.

It’s then that he begins to make his way across the middle of a well-lit piazza, and although the music continues to unnerve us, there’s a noticable slackening in our fear for the man— even a director as often deranged and illogical as Dario Argento couldn’t possibly stage an assailant looming up from behind to rip out his throat after placing the character in such a wide-open space. The camera continues to track along with the man, and then stops as the dog senses something wrong and begins to bark. The man is visibly concerned, but Argento reassures us with a extremely wide and high shot that there is nothing within 100 feet on any side of man or dog that could pose any threat. Despite the dog’s inexplicable reaction, there doesn’t seem to be any immediate danger. The man pets the dog and tries to reassure him, and himself. “Easy. What is it?” Cut to a shot of the man framed in the foreground against a building decorated on the façade with a row of gigantic pillars. The man turns toward the building and proceeds down the Z-axis with the dog. “Come on. Let’s go home.”

It’s then that he begins to make his way across the middle of a well-lit piazza, and although the music continues to unnerve us, there’s a noticable slackening in our fear for the man— even a director as often deranged and illogical as Dario Argento couldn’t possibly stage an assailant looming up from behind to rip out his throat after placing the character in such a wide-open space. The camera continues to track along with the man, and then stops as the dog senses something wrong and begins to bark. The man is visibly concerned, but Argento reassures us with a extremely wide and high shot that there is nothing within 100 feet on any side of man or dog that could pose any threat. Despite the dog’s inexplicable reaction, there doesn’t seem to be any immediate danger. The man pets the dog and tries to reassure him, and himself. “Easy. What is it?” Cut to a shot of the man framed in the foreground against a building decorated on the façade with a row of gigantic pillars. The man turns toward the building and proceeds down the Z-axis with the dog. “Come on. Let’s go home.”The camera begins to dolly in as he moves toward the building. Suddenly there’s another cut— the camera is now moving laterally within another grouping of pillars. We quickly realize it’s not the pillars we’ve just seen, but another—we’re looking at the man as he continues to move across the piazza from inside the formations of another building we weren’t previously aware was even there. Suddenly that swell of fear rises in our stomach again—is this the place from which the killer will emerge? Cut to another long shot from above, as the dog continues barking, even more agitated now. The man is becoming concerned too, swinging his cane to all sides in fear of discovering someone or something which may be much too near. “Who’s there? Easy, boy.” The music continues, unchanged from when it started, its jingling theme repeating and becoming more and more ominous. Cut to a close shot of the dog barking, the large red cross on its collar standing out in stark relief against the darkness of the night that comprises the rest of the tightly framed shot. Cut to a medium close-up of the man, the first pillared building still in the background. He is looking out at the night, obviously seeing nothing, and just as obviously sensing something. “What is it? What’s happening?”

A very quick cut to the dog, suddenly quiet—it sees something. Cut to a closer shot of the façade of the building. Something is moving across the face of the front wall, under the lights—a small flock of birds. Cut back to the man, who turns sharply to the building and shouts, “Who’s there?” Still we’re aware that he’s in the middle of the piazza, unprotected but for the distance he remains from anyone, or even anything that could hide anyone, yet the sense of impending doom is almost unbearable now. If only we could reconcile it with what we know about where the man is—how could anything possibly happen? We see the dog, now strangely calm, look toward the building. Suddenly we cut to a shot of the building from head on, which then tilts up toward the blackness of the night sky. The blackness has almost completely engulfed the frame when, again suddenly, there is a jarring, unnerving cut-in to a medium close-up of the statue that resides at the top of the columns—the phoenix rising from the ashes, surrounded by nothing but pitch black. And then another jarring cut-in to a slightly closer shot of the same statue (which Argento undoubtedly noticed bears a striking resemblance to the statue of the demon Pazuzu unearthed by Father Merrin at the beginning of The Exorcist). Then, from a disorienting distance above, Argento’s camera swoops down toward, and then past, the man and his dog, as if borne on the wings of that nightmarish stone bird which has come to life simply to torment the man a little further, or perhaps to snap his head off in its beak.

The man looks around, and we see what he cannot—a series of vaporous, amorphous shadows swooping across the face of the columned building. The music has now broken from its seductive relentlessness into a kind of techno-tribal drum beat laid over a thrumming, hellish synthesizer bed, perhaps to accompany the rising of the phoenix again. What other creature could possibly find enough advantage to approach this man suddenly enough to deliver the kill, and the fright, that Argento seems to building toward, even as he cuts again to a long shot of the man and his dog surrounded by the relative comfort of isolation at the center of the piazza? The dog has calmed now, but is still attentive to what looks like movement (it’s those birds fluttering again), against which the soundtrack booms and wails in contrast to the relative stasis inside the frame. More sitting quietly, listening, waiting, as the frightening banshees on the soundtrack subside.

The dog, seemingly placated, its tongue hanging out in a mild pant, turns once again, then gives the blind man a tiny glance that he couldn’t possibly be aware of… and then lunges at him, taking the man’s throat in his powerful jaws and tearing it out. Argento then cuts to a familiar long shot of the man and his dog, still surrounded by only the quiet of the piazza at night, the dog continuing to rip at the flesh of his master. The ominous drum beating, the lurid and pulsating low chords of a synthesizer, and the wails of the banshees have returned to the soundtrack.

The man tries in vain to fight off the beast, which has simply too strong a hold on what’s left of his neck. In a tight close-up emphasizing his unseeing eyes, which have been exposed by the falling away of his dark glasses during the attack, he gives up the last vestige of fight, and his life, in a spray of bright red blood from his mouth. Another long shot, and then back in again tight on the dog, feasting on the body of the blind man, which rests just beneath the Panavision frame line. The dog is now yanking up just enough gristle and viscera to assure us that it hasn’t suddenly had a change of heart and is now licking the wounds it so violently inflicted just a moment before. Suddenly we see two policemen, who themselves have just spotted the strange scene. As they run toward the dog, we cut one last time to a long shot of the piazza, the policemen running in from the left, shouting at the animal, which has picked up and started to run off toward the right, leaving the mangled, lifeless body of the blind man for the others of his kind. A perfect moment from Dario Argento’s Suspiria.

The man tries in vain to fight off the beast, which has simply too strong a hold on what’s left of his neck. In a tight close-up emphasizing his unseeing eyes, which have been exposed by the falling away of his dark glasses during the attack, he gives up the last vestige of fight, and his life, in a spray of bright red blood from his mouth. Another long shot, and then back in again tight on the dog, feasting on the body of the blind man, which rests just beneath the Panavision frame line. The dog is now yanking up just enough gristle and viscera to assure us that it hasn’t suddenly had a change of heart and is now licking the wounds it so violently inflicted just a moment before. Suddenly we see two policemen, who themselves have just spotted the strange scene. As they run toward the dog, we cut one last time to a long shot of the piazza, the policemen running in from the left, shouting at the animal, which has picked up and started to run off toward the right, leaving the mangled, lifeless body of the blind man for the others of his kind. A perfect moment from Dario Argento’s Suspiria. 6) Favorite John Ford movie

6) Favorite John Ford movieSuddenly, I’m glad the professor put “favorite” instead of “best” too. I know there are probably many other Ford films that might deserve consideration as the “best,” but we’re talking favorite, and so the clear choice for me is Young Mr. Lincoln. I saw it again recently and was struck by how imperfect it is—there’s an awful lot of cornball humor, the climactic courtroom scene is not exactly staged out of procedural verisimilitude, and it often sways toward the overly sentimental. But there’s no underestimating the power of the mythical center of the movie—Henry Fonda’s magnetic, understated, lived-in performance as Abraham Lincoln. There may be no one person in American history so mythologized, dissected and perhaps even misunderstood than Lincoln, and the movie is certainly not about undercutting or investigating what we, as a nation, understand to be his character. Instead, it examines the roots of that mythology, accepts it, adds to it. But what’s remarkable is how, at the same time, Fonda finds a recognizable person under the false nose and high brow and veneer of historical truth, which serves to expand Ford’s understandable investment in Lincoln as the ultimate American. Fonda makes us believe, in a fuller dramatic sense than many of the historical regurgitations Lincoln has been subject to, that the ultimate American may have been what we’d like to think of as the best in ourselves, but he also came from a recognizable place and had no real reason to believe he would be one to galvanize the direction of the country. When he walks up the road toward his destiny at the end of Ford’s film, there’s a finer feeling, to go along with the goosebumps raised by the perfection of the moment, of glory and ambiguity, in knowing where Lincoln came from, what lay in store for him, and what lay in store for the country in the decades after his passing into legend.

7) The inverse of a question from the last quiz: What film artist (director, actor, screenwriter, whatever) has the least–deserved good reputation, artistically speaking? And who would you replace him/her with on that pedestal? At this point in the game, after an eight-year run from 1997 to 2005 than produced glossy, pretentious, thoughtless crap like G.I.Jane, Gladiator, Hannibal, Black Hawk Down and the relatively intelligent, if still stultifying, Kingdom of Heaven, I wonder if it’s not time to show Ridley Scott the door.

Let him go off in a corner, chomp his cigar and glower about how no one gives him any respect as an artist. I’d rather the critical respect he does manage to garner, along with his influence with the studios and the budgets that go hand-in-hand with that influence, be transferred to someone like Joe Johnston, a genuinely gifted director whose style and demeanor are far more reminiscent of the studio hands of old, like William Wyler or Howard Hawks, who took assignments and, through their talent and professionalism, often spun gold from them.

Let him go off in a corner, chomp his cigar and glower about how no one gives him any respect as an artist. I’d rather the critical respect he does manage to garner, along with his influence with the studios and the budgets that go hand-in-hand with that influence, be transferred to someone like Joe Johnston, a genuinely gifted director whose style and demeanor are far more reminiscent of the studio hands of old, like William Wyler or Howard Hawks, who took assignments and, through their talent and professionalism, often spun gold from them. I’m not suggesting Johnston is at the level of a Hawks or Wyler, just that he’s got that kind of rock-solid foundation beneath him, one that allows him to trust the thrust of his characters, and his actors, and to embue outlandish action and special effects sequences with a human element that tends to keep them specially effective. As good as he is with large-scale action (Hidalgo, Jurassic Park III), I can think of great acting and character turns from every one of his movies—Bonnie Hunt in Jumanji, Chris Cooper and Jake Gyllenhaal in October Sky,

I’m not suggesting Johnston is at the level of a Hawks or Wyler, just that he’s got that kind of rock-solid foundation beneath him, one that allows him to trust the thrust of his characters, and his actors, and to embue outlandish action and special effects sequences with a human element that tends to keep them specially effective. As good as he is with large-scale action (Hidalgo, Jurassic Park III), I can think of great acting and character turns from every one of his movies—Bonnie Hunt in Jumanji, Chris Cooper and Jake Gyllenhaal in October Sky,  Timothy Dalton and Alan Arkin in The Rocketeer, Tea Leoni and William H. Macy in Jurassic Park III, Rick Moranis in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Viggo Mortensen, Omar Sharif and Zuleikha Robinson in Hidalgo. A glance at IMDb reveals that, in the wake of Hidalgo's less-than-triumphant run at the box office in 2004, Johnston has yet to find himself at the helm of his next film. I hope that changes very soon.

Timothy Dalton and Alan Arkin in The Rocketeer, Tea Leoni and William H. Macy in Jurassic Park III, Rick Moranis in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Viggo Mortensen, Omar Sharif and Zuleikha Robinson in Hidalgo. A glance at IMDb reveals that, in the wake of Hidalgo's less-than-triumphant run at the box office in 2004, Johnston has yet to find himself at the helm of his next film. I hope that changes very soon. 8) Barbara Stanwyck or Ida Lupino? Stanwyck. I love Ida Lupino, but if Barbara Stanwyck never did another movie after The Lady Eve she’d still win. Of course, she also did Forty Guns, Sorry, Wrong Number, Meet John Doe, Double Indemnity, Night Nurse, Christmas in Connecticut, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Annie Oakley, Stella Dallas, Clash By Night, Golden Boy and Ball of Fire (and by God, I will see The Bitter Tea of General Yen!) I dug her in The Big Valley too!

8) Barbara Stanwyck or Ida Lupino? Stanwyck. I love Ida Lupino, but if Barbara Stanwyck never did another movie after The Lady Eve she’d still win. Of course, she also did Forty Guns, Sorry, Wrong Number, Meet John Doe, Double Indemnity, Night Nurse, Christmas in Connecticut, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Annie Oakley, Stella Dallas, Clash By Night, Golden Boy and Ball of Fire (and by God, I will see The Bitter Tea of General Yen!) I dug her in The Big Valley too!  9) Showgirls-- yes or no?

9) Showgirls-- yes or no?Absolutely, and preferably with a double cheeseburger and a side of chili cheese fries.

10) Most exotic or otherwise unusual place in which you ever saw a movie My soon-to-be wife took me to see Singin’ in the Rain at the Hollywood Bowl for my 30th birthday—Donald O’Connor, Gene Kelly, Debbie Reynolds, Adolph Green and Betty Comden were all in attendance, and I’d never seen the movie before. If there is such a thing as the magic of Hollywood, it’s just not possible that the Bowl wasn’t coursing with it that night. As we headed down Highland and toward our car afterward, I started whistling the titular tune and swung on a street lamp in imitation of Gene Kelly, and even though no one would ever mistake me for anything like the lithe, athletic Kelly, I was drunk on movie love and real love, and I didn’t care a damn if I looked like the stupidest man alive.

10) Most exotic or otherwise unusual place in which you ever saw a movie My soon-to-be wife took me to see Singin’ in the Rain at the Hollywood Bowl for my 30th birthday—Donald O’Connor, Gene Kelly, Debbie Reynolds, Adolph Green and Betty Comden were all in attendance, and I’d never seen the movie before. If there is such a thing as the magic of Hollywood, it’s just not possible that the Bowl wasn’t coursing with it that night. As we headed down Highland and toward our car afterward, I started whistling the titular tune and swung on a street lamp in imitation of Gene Kelly, and even though no one would ever mistake me for anything like the lithe, athletic Kelly, I was drunk on movie love and real love, and I didn’t care a damn if I looked like the stupidest man alive.Coming a close second: Watching my first movie on HBO-- Taxi Driver-- during a break in the filming of Animal House at the Sigma Nu house, with John Belushi, Judy Jacklin and a host of hyperactive and excited extras all sitting around the TV, juggling the giddiness of being on a film set and casually watching a movie with Belushi, whose star had just begun to rise, with the insinuating terror and loneliness of the movie we were watching.

11) Favorite Robert Altman movie

11) Favorite Robert Altman moviePut the following four on a spit and rotate until brown-- Nashville, The Long Goodbye, California Split and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson. But if pressed, I’d still have to say Nashville, the Altman movie where “it” all comes together and swirls like a gathering electrical storm, an amazing confluence of talent, inspiration, luck and the happy convivality of chaos, ordered and endured.

12) Best argument for allowing rock stars to participate in the making of movies

12) Best argument for allowing rock stars to participate in the making of moviesI love Brian’s answer: George Harrison’s Handmade Films production division.

My answer: James Taylor and Dennis Wilson in Two-Lane Blacktop.

13) Describe a transcendent moment in a film (a moment when you realized a film that just seemed routine or merely interesting before had become become something much more)

The dance musicals of Astaire and Rogers are, at their best, themselves transcendent, and Follow the Fleet informs the moment when the 1981 movie version of Dennis Potter’s Pennies from Heaven soared from engaging and disturbing to heights of emotional profundity for me. The moment comes late in the movie, when the characters played by Steve Martin and Bernadette Peters, sit inside a grand, eeriely quiet movie palace watching the Mark Sandrich-directed Astaire-and-Rogers vehicle. Just as characters have lip-synched to popular recordings of 1930s pop tunes throughout the film, Martin and Peters stand up and begin to dance at the bottom of the screen, their movements synchronized perfectly with those of Fred and Ginger, until they become one with the film and are suddenly the stars of a spectacular Gordon Willis-lit Panavision version of Fleet that expresses all the romantic desire of these two dreamers, who have no idea that the wheels of their doom are already in motion.

When I saw this movie on the opening weekend of its disastrous theatrical run (it was MGM’s big Christmas movie, and they marketed it like it was just another Steve Martin vehicle), I had not much interest in it and certainly nothing at stake in it being either bad or good. But it immediately floored me with its originality and MGM musical-inspired flights of fancy, and drudgery too—the movie’s big theme is the contrast between the glossy, pop-fed fantasies of people whose own lives were being slowly smothered by the insistent economic realities of the Great Depression. The movie definitely had me in its spell almost from the beginning, but when Martin and Peters took the stage in that movie theater, I shocked myself by the tears that had started to flow from my eyes, as if I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. In her review of Pennies from Heaven, Pauline Kael said: “(The moment) makes you gasp. Do Steve Martin and Bernadette Peters really dare to put themselves in Astaire and Rogers’s place? And yet they bring it off.” She’s right— it’s not a moment of hubris, but one of genuine connection with what feeds these desperate characters, a moment fed also by the spectacular talent that these two actors—these two dancers— bring to such a pivotal moment.

When I saw this movie on the opening weekend of its disastrous theatrical run (it was MGM’s big Christmas movie, and they marketed it like it was just another Steve Martin vehicle), I had not much interest in it and certainly nothing at stake in it being either bad or good. But it immediately floored me with its originality and MGM musical-inspired flights of fancy, and drudgery too—the movie’s big theme is the contrast between the glossy, pop-fed fantasies of people whose own lives were being slowly smothered by the insistent economic realities of the Great Depression. The movie definitely had me in its spell almost from the beginning, but when Martin and Peters took the stage in that movie theater, I shocked myself by the tears that had started to flow from my eyes, as if I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. In her review of Pennies from Heaven, Pauline Kael said: “(The moment) makes you gasp. Do Steve Martin and Bernadette Peters really dare to put themselves in Astaire and Rogers’s place? And yet they bring it off.” She’s right— it’s not a moment of hubris, but one of genuine connection with what feeds these desperate characters, a moment fed also by the spectacular talent that these two actors—these two dancers— bring to such a pivotal moment.  I’d also like to mention The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), a spectacular feat of silhouette animation based on tales from The Arabian Nights, which is purported to be the very first feature-length (at 65 minutes) animated film. The entire movie is constructed from cardboard figures with moveable parts cut out with scissors and animated to tell a story with largely suggestive silhouetted imagery, and the effect is mesmerizing. It’s one of those films that is impossible to stop watching once you’ve started. Directed by Lotte Reiniger, its subject is a fairy tale, but its story is so intertwined and so compelled by the singular art of its technique that it practically defines transcendent.

I’d also like to mention The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), a spectacular feat of silhouette animation based on tales from The Arabian Nights, which is purported to be the very first feature-length (at 65 minutes) animated film. The entire movie is constructed from cardboard figures with moveable parts cut out with scissors and animated to tell a story with largely suggestive silhouetted imagery, and the effect is mesmerizing. It’s one of those films that is impossible to stop watching once you’ve started. Directed by Lotte Reiniger, its subject is a fairy tale, but its story is so intertwined and so compelled by the singular art of its technique that it practically defines transcendent. 14) Gina Gershon or Jennifer Tilly?

14) Gina Gershon or Jennifer Tilly?Tilly, of course. When I first saw No Small Affair, I thought Jon Crier was the biggest idiot alive to not dump his ridiculous obsession with Demi Moore and turn his attention to the beauty right there in his inner circle who obviously, inexplicably, had a thing for him. You know Tilly’s the “best friend” here, though, because she wears glasses! But there’s no eyesight problem extreme enough to mask her charms. She has endured through terrific movies like Let It Ride, The Fabulous Baker Boys and Bound and scores of other movies and TV projects, most of which were unworthy of her sexy demeanor and talent and depth as an actress (don’t let that voice fool you!). She even got an Oscar nomination, arguably exploiting her public misperception as a shrill ditz, in Bullets Over Broadway. But her unlikely hero has been, of all creatures great or small, the killer doll Chucky. In Ronny Yu’s Bride of Chucky, and most significantly in Don Mancini’s Seed of Chucky, she began a brilliant process of deconstructing the very broad and public persona of “Jennifer Tilly,” giving herself no quarter, and none to the brutal business of Hollywood either. I’ve never seen such brazen, giddy and brave self-parody, especially in the face of all the insistent casting of tanned-and-buffed WB beauties that studios seem convinced we all want desperately to see. I want desperately to see Tilly in whatever she can get her hands on and her long nails into. Here’s hoping Chucky goes on another meta-movie rampage real soon.

15) Favorite Frank Capra movie

15) Favorite Frank Capra movieIt’s a Wonderful Life. Despite its overexposure, it’s just too damn good to get killed by being turned into a holiday requirement. I thought they got me before, but now, as a father of two, Zuzu’s petals represent complete and honorable emotional devastation.

16) The scene you most wish you could have witnessed being filmed I’d love to cite a great classic moment of cinema here, but I think I fall in line with the thinking that, especially in this age of “making-of” documentaries, DVD commentaries and every other kind of lifting of the veil, there are some things about movies that I think I’d rather have shrouded in mystery, or at least my own imagination. Seeing some of those great scenes being put together in the drudgery and glacial pace of a film set would be just too much information for me, I think. (Ask me if I’d wouldn’t have loved to simply visit the set of, say, Once Upon a Time in the West, just to meet a certain actress, or a director, or any number of other great actors involved, and my answer might well be different.) However, if I’m gonna pick one scene to witness being filmed, I’ll pick one that probably was close to as much fun to watch being created as it was to see in the finished film. My choice: the “French Mistake” production number and ensuing fight from Blazing Saddles. Piss on you! I’m workin’ for Mel Brooks!

16) The scene you most wish you could have witnessed being filmed I’d love to cite a great classic moment of cinema here, but I think I fall in line with the thinking that, especially in this age of “making-of” documentaries, DVD commentaries and every other kind of lifting of the veil, there are some things about movies that I think I’d rather have shrouded in mystery, or at least my own imagination. Seeing some of those great scenes being put together in the drudgery and glacial pace of a film set would be just too much information for me, I think. (Ask me if I’d wouldn’t have loved to simply visit the set of, say, Once Upon a Time in the West, just to meet a certain actress, or a director, or any number of other great actors involved, and my answer might well be different.) However, if I’m gonna pick one scene to witness being filmed, I’ll pick one that probably was close to as much fun to watch being created as it was to see in the finished film. My choice: the “French Mistake” production number and ensuing fight from Blazing Saddles. Piss on you! I’m workin’ for Mel Brooks! 17) Robert Ryan or Richard Widmark?

17) Robert Ryan or Richard Widmark?I think very highly of Richard Widmark—he was Madigan for Don Siegel and Skip McCoy for Sam Fuller, after all. But there’s a depth to Ryan—sometimes there’s a core of unreachable sadness there, sometimes its hard-boiled cynicism, sometimes it’s fear, sometimes a potent mixture of them all—that makes him continually fascinating to me. There was a period last year where it seemed like every third movie I was seeing on Turner Classic Movies starred Ryan, and I was made aware of just how many movies he starred in in his day. Not all of them were great, or even good, but how could anyone reasonably complain about a resume that includes Bad Day at Black Rock, The Tall Men, The Wild Bunch, On Dangerous Ground, House of Bamboo, The Dirty Dozen, The Naked Spur, Day of the Outlaw, The Set-Up and Lawman? If I had to pick one performance, it’d probably be his Deke Thornton from The Wild Bunch. But why pick one? Watch ‘em all.

18) Name a movie that inspired you to walk out before it was finished

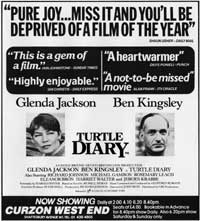

18) Name a movie that inspired you to walk out before it was finishedI stayed to the bitter end of Mississippi Burning, but I bolted out of fear of rigor mortis from Turtle Diary, a fairly innocuous movie written by Harold Pinter (never one of my favorites) starring Ben Kingsley and Glenda Jackson as two cloistered souls who bond over a decision to free a bunch of turtles from captivity and release them into the sea. Directed by John Irvin (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Dogs of War, Hamburger Hill), it might very well be a perfectly okay little movie. But on that rainy Sunday afternoon when I saw it, all those caged animal-repressed spirit metaphors floating around in the morose atmosphere created by Jackson and Kingsley trying to out-under-emote each other made that little crackerbox cinema I was sitting in feel more and more like a long, narrow sarcophagus from which I just had to escape.

19) Favorite political movie

19) Favorite political movieThe BEST answer is Videodrome, but my own personal favorite is Secret Honor, a brilliant, infuriating, surprisingly empathetic dissection of the pathlogy of Richard Nixon and, by extension, the hellbound trajectory of American politics left in his wake. (Thanks to Tom Sutpen for the great screen grab.)

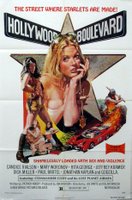

20) Your favorite movie poster/one-sheet, or the one you’d most like to own

I own Blow Out, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, Nashville, the Jack Davis rerelease one-sheet for The Long Goodbye and Lisztomania, so what else would I need, beside actual wall space (in my own home theater, perhaps?) on which to hang them? Well, maybe the one-sheet for Charley Varrick.Or perhaps Hollywood Boulevard. Or an original British version of the Hammer classic Plague of the Zombies.

(Thanks to That Little Round-Headed Boy for the inspiration!)

21) Jeff Bridges or Jeff Goldblum?

21) Jeff Bridges or Jeff Goldblum?The Brundlefly carries a lot of weight. But then again, way out West there was a fella—fella I wanna tell you about—fella by the name of Jeff Lebowski. At least, that’s the handle his lovin’ parents gave him. But he never had much use for it himself. This Lebowski, he called himself the Dude. Now, Dude, that’s a name no one would self-apply where I come from. But then, there was a whole lot about the Dude that didn’t make sense to me. Sometimes there’s a man— I won’t say a hero, ‘cause what’ a hero? But sometimes there’s a man— and I’m talkin’ about the Dude here. Sometimes there’s a man who, well, he’s the man for his time and place. He fits right in there. And that’s the Dude.

22) Favorite Ken Russell movie The Devils, which is, I think, also Russell’s best movie by a country mile. The first time I saw it (luckily enough, on the big screen about 20 years ago), it blew me away. The movie is about hysteria, and it has been steeped, of course, in its own measure of hysteria (it is a Ken Russell movie, after all), but I was struck by just how seriously it takes that atmosphere of hysteria and religious terror, and by its fatalistic conviction. It’s also one of the few movies I’ve seen made during that three or four-year period after the advent of the ratings system, when “X” ratings for serious adult material (not pornography) were still fairly common, that 20 or so years later seemed to still actually deserve its stiff certificate. (Midnight Cowboy, an “X” upon release in 1969, was rereleased wthout a cut many years later and was re-rated “R.” A frame or two missing from the theater scene and it might even get a PG-13 today.) I also think very highly of Kathleen Turner and Anthony Perkins in the uncut Crimes of Passion (avoid the disastrous “R” version, which is a full two stars below the unexpurgated version on the Leonard Maltin scale). And I have an irrational, nearly indefensible fondness for Lisztomania.

22) Favorite Ken Russell movie The Devils, which is, I think, also Russell’s best movie by a country mile. The first time I saw it (luckily enough, on the big screen about 20 years ago), it blew me away. The movie is about hysteria, and it has been steeped, of course, in its own measure of hysteria (it is a Ken Russell movie, after all), but I was struck by just how seriously it takes that atmosphere of hysteria and religious terror, and by its fatalistic conviction. It’s also one of the few movies I’ve seen made during that three or four-year period after the advent of the ratings system, when “X” ratings for serious adult material (not pornography) were still fairly common, that 20 or so years later seemed to still actually deserve its stiff certificate. (Midnight Cowboy, an “X” upon release in 1969, was rereleased wthout a cut many years later and was re-rated “R.” A frame or two missing from the theater scene and it might even get a PG-13 today.) I also think very highly of Kathleen Turner and Anthony Perkins in the uncut Crimes of Passion (avoid the disastrous “R” version, which is a full two stars below the unexpurgated version on the Leonard Maltin scale). And I have an irrational, nearly indefensible fondness for Lisztomania.23) Accepting the conventional wisdom that 1970-1975 marked a golden age of American filmmaking in which artistic ambition and popular acceptance were not mutually exclusive, what for you was this golden age’s high point? (Could be a movie, a trend, the emergence of a star, whatever)

Charlie (Harvey Keitel) holding his hand over the flame in Mean Streets, and that film’s subsequent opening credits scored to the Ronettes’ Be My Baby (it occurs to me this would also be a candidate for a “perfect moment”); the first two Godfather films;

Charlie (Harvey Keitel) holding his hand over the flame in Mean Streets, and that film’s subsequent opening credits scored to the Ronettes’ Be My Baby (it occurs to me this would also be a candidate for a “perfect moment”); the first two Godfather films; the emergence, unpredictable output and perseverance of Robert Altman; and Robert Aldrich’s sublime and brutal Emperor of the North Pole starring Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine and Keith Carradine and the spectacular Oregon countryside.

the emergence, unpredictable output and perseverance of Robert Altman; and Robert Aldrich’s sublime and brutal Emperor of the North Pole starring Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine and Keith Carradine and the spectacular Oregon countryside. 24) Grace Kelly or Ava Gardner?

24) Grace Kelly or Ava Gardner?Ava for The Killers, but ultimately Grace for Rear Window.

25) With total disregard for whether it would ever actually be considered, even in this age of movie recycling, what film exists that you feel might actually warrant a sequel, or would produce a sequel you’d actually be interested in seeing?

Though I was intrigued by the possibility of Robert Altman directing Nashville Nashville, I’m kind of glad the project felt apart. But I’d be first in line if Brad Bird ever decided to direct The Incredibles II, or if Peter Jackson got down and dirty again for Dead Alive II.

Whew!

8 comments:

Your description of That Moment from Suspiria makes me want to run into the next room, break out my DVD and watch the film. Dario Argento IS (or at least WAS) cinema.

Also, why the hell didn't I think of Dead Alive II? Good on ya!

Dennis, thought I was gonna turn purple holding my breath and getting to the end of the SUSPIRIA post! Another film I gotta see! Now, you've probably covered this in detail before I started visiting, but you must tell me sometime about your ANIMAL HOUSE experience. You were in the movie?

Longest survey answers ever!

I added you to my blog links, finally. Don't know what took me so long.

good quiz...great pictures. You are very complete in your answers.

--RC of strangeculture.blogspot.com

I enjoyed reading your answers, especially your detailed response to "perfect moment" since I also selected a moment in Suspiria as my own "perfect moment". Argento has many of them in his pre-Two Evil Eyes films. Sadly nothing he's done since Two Evil Eyes has impressed me much.

I also liked your defense of The Devils which is one of my favorite films. I may be one of few, but I think Russell's made a lot of good movies.

Your posts are so long it's hard to scroll through them and find the next blog entry down.

Can you widen the columns at all?

And get that damn recent activity button working so I can keep track of all the comments!

- The Mysterious ADRI;AN BET.AMAX (IMF 15978)

TLRHB: Actually, I've never covered it in any detail. Just waiting for the right time, I guess. But yes, Blaaagh and I, best friends for 29 years, met on the set of Animal House, where we were both cast as extras-- Delta pledges. I've been wanting to collect his anecdotes and mine and write some sort of definitive history of the production from the extras' point of view, and now that he's moved back to Eugene, I think at some point I'll go up for a visit, get a few shots of some of the most recognizable locales, and then maybe it'll finally be time to put that article together. In the meantime, here's a link to a previous post, and if you scroll down to the bottom there's a screen grab from the movie. I'm the guy in the blue plaid bathrobe all the way to the right of frame.

Pardon me-- I'm second from the right in the blue plaid bathrobe.

Post a Comment