R.I.P., RICHARD PRYOR: 1940 - 2005

“Are you laughing or crying

Are you killing or dying tonight?”

- “Comedienne,” Fountains of Wayne

Like a lot of folks who grew up in rural America in the ‘70s, I really had no real awareness of Richard Pryor until he hosted Saturday Night Live in December 1975. The sketch, entitled ”Racist Word Association,” in which Pryor applies for a janitorial job and is subjected to an increasingly hostile, racially loaded exercise in word association from personnel manager Chevy Chase, crystallized Pryor’s wild-eyed, go-for-the-jugular approach to racial politics, behavior and misbehavior. Caucasians like me, ones with precious little exposure to any ethnic minorities and outsiders (I grew up in the Eastern Oregon desert, where if you weren’t first or second-generation Irish, you were the odd man out), sensed in Pryor a level of danger, of unpredictability, of unwillingness to accede to the white man in the ways more typical of black performers of his generation.

That same year I saw Blazing Saddles, a movie that affected my views of race and racism in perhaps a more profound and lasting way that even the double-edged satire of All in the Family. Blazing Saddles is, of course, a Mel Brooks movie, but it’s a Mel Brooks movie written with three other writers, including a young Richard Pryor. When the movie was filmed in 1973, Pryor had been seen with Diana Ross in Lady Sings the Blues, but he was too much of an unknown for Warner Bros., who refused to allow him to play the lead character in Saddles, a black sheriff in the racist American old West of the mid 1800s, even though he was director Brooks’ first choice. How much more astringent would the laughs have been, how many of them would have caught in the throat like a prickly tumbleweed, had Pryor played Sheriff Bart to Gene Wilder’s Waco Kid instead of the more benign Cleavon Little? Had they been brave enough to let Brooks see his vision through, Warner Bros. might also have allowed Brooks to keep the original title: Tex X.

January 1, 1976, pointedly enough, saw the high-profile release of Pryor’s caustically funny record album Bicentennial Nigger. By then I had become aware enough of Pryor and the profane, driven nature of his humorous charge, to run out and pick up a copy. I had to hear it for myself, and hear it I did. This was racially provocative humor loaded with outrageous caricature (of both blacks and whites) and razor-sharp (all the better for slashing) social observation borne of bitterness and struggle—all of which made its title, and its timely appearance, even more appropriate than I could gauge during that bicentennial summer, when I was only 16 years old and only just beginning to become familiar with the comedian’s rhythms and fierce, brave abandon. Listening to Bicentennial Nigger, I was aware even back then, though, that there was something missing. The record seemed half-formed to me—Pryor was slaying the (presumably black) audience in attendance for the recording (including an I-wonder-how-embarrassed Natalie Cole)—but I wasn’t always fully aware of why. Were they so enraptured by his cosmically liberating use of profanity that every utterance sent them into hysterical laughter? If so (and that’s how it seemed to me), then wasn’t Pryor’s comic vision somewhat limited, even hampered by the incessant variations on “motherfucker” that seemed to flow from him independent of judgment or control?

January 1, 1976, pointedly enough, saw the high-profile release of Pryor’s caustically funny record album Bicentennial Nigger. By then I had become aware enough of Pryor and the profane, driven nature of his humorous charge, to run out and pick up a copy. I had to hear it for myself, and hear it I did. This was racially provocative humor loaded with outrageous caricature (of both blacks and whites) and razor-sharp (all the better for slashing) social observation borne of bitterness and struggle—all of which made its title, and its timely appearance, even more appropriate than I could gauge during that bicentennial summer, when I was only 16 years old and only just beginning to become familiar with the comedian’s rhythms and fierce, brave abandon. Listening to Bicentennial Nigger, I was aware even back then, though, that there was something missing. The record seemed half-formed to me—Pryor was slaying the (presumably black) audience in attendance for the recording (including an I-wonder-how-embarrassed Natalie Cole)—but I wasn’t always fully aware of why. Were they so enraptured by his cosmically liberating use of profanity that every utterance sent them into hysterical laughter? If so (and that’s how it seemed to me), then wasn’t Pryor’s comic vision somewhat limited, even hampered by the incessant variations on “motherfucker” that seemed to flow from him independent of judgment or control? Later that year, I would get a hint of what I was missing when I saw Silver Streak, the movie that fulfilled Mel Brooks’ dream of pairing Wilder and Pryor on screen. The movie is an insistently routine (was any movie directed by Arthur Hiller ever anything but?) Hitchcock knockoff—Wilder sees a murder while riding aboard the titular train, and Pryor is the streetwise black guy who befriends him and helps him get to the bottom of the movie’s none-too-riveting mystery. The success of the Wilder-Pryor team was solidified in the movie’s comic centerpiece, set inside a train station, when, to avoid capture by the authorities pursuing them, Pryor disguises Wilder in blackface, satin jacket and knit cap and tries to teach him some funky moves.

But the scene is all Wilder—the white guy who can’t dance, can’t move, being shepherded by the cool black guy with the real moves who’s straitjacketed into a routine straight-man role. And though the movie toys with letting Pryor fill out the rough-edged boundaries of the character with his hostile physicality, Silver Streak ends with Pryor letting down his guard and giving Wilder a big grin and a hug—so (white) audiences could see that this guy who seemed so tough and dangerous, why, he was really just a softie at heart. And that’s the antithesis of what Pryor’s persona had been about up to and even including parts of Silver Streak-- I’ll never forget the authentic anger in Pryor’s eyes, the sense that someone might seriously get stomped, when the movie’s villain, Patrick McGoohan, calls Pryor’s character an “ignorant nigger!” At that moment, before Hiller and screenwriter Colin Higgins serve up Pryor Lite for the movie’s conclusion, you’d never believe that Pryor had anything but contempt for the parade of Caucasians and other non-blacks who must have hurled that epithet at him in real life thousands of times before the cameras rolled on that scene. (Wouldn’t outtakes of this segment of the shoot be particularly interesting?) Yet seeing Pryor move in Silver Streak gave those of us who had never see him perform his stand-up routine a tantalizing hint of what the comedian was capable of, in fact, what he was fulfilling nightly in his stand-up act. His ill-fated TV series, The Richard Pryor Show, gave further hints, and also peeled back a layer or two of his provocative tendencies while making plainer than ever the rage attendant a black man, despite his celebrity, living in a world of surface and subterranean racism. Of course, the show didn’t last long, and Pryor appeared headed toward a career filled with Silver Streak-sized hits that wouldn’t come close to tapping his predatory energy and intensity. (Only one would—Paul Schrader’s directorial debut, Blue Collar.)

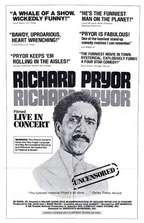

But the scene is all Wilder—the white guy who can’t dance, can’t move, being shepherded by the cool black guy with the real moves who’s straitjacketed into a routine straight-man role. And though the movie toys with letting Pryor fill out the rough-edged boundaries of the character with his hostile physicality, Silver Streak ends with Pryor letting down his guard and giving Wilder a big grin and a hug—so (white) audiences could see that this guy who seemed so tough and dangerous, why, he was really just a softie at heart. And that’s the antithesis of what Pryor’s persona had been about up to and even including parts of Silver Streak-- I’ll never forget the authentic anger in Pryor’s eyes, the sense that someone might seriously get stomped, when the movie’s villain, Patrick McGoohan, calls Pryor’s character an “ignorant nigger!” At that moment, before Hiller and screenwriter Colin Higgins serve up Pryor Lite for the movie’s conclusion, you’d never believe that Pryor had anything but contempt for the parade of Caucasians and other non-blacks who must have hurled that epithet at him in real life thousands of times before the cameras rolled on that scene. (Wouldn’t outtakes of this segment of the shoot be particularly interesting?) Yet seeing Pryor move in Silver Streak gave those of us who had never see him perform his stand-up routine a tantalizing hint of what the comedian was capable of, in fact, what he was fulfilling nightly in his stand-up act. His ill-fated TV series, The Richard Pryor Show, gave further hints, and also peeled back a layer or two of his provocative tendencies while making plainer than ever the rage attendant a black man, despite his celebrity, living in a world of surface and subterranean racism. Of course, the show didn’t last long, and Pryor appeared headed toward a career filled with Silver Streak-sized hits that wouldn’t come close to tapping his predatory energy and intensity. (Only one would—Paul Schrader’s directorial debut, Blue Collar.)  The quote from Lorne Michaels in the ad for Richard Pryor Live in Concert insisted that Pryor was the funniest man on the planet, and try as I might, based on what I’d seen of Pryor up till then, I just couldn’t figure out how this comment could be construed as anything but hype. Sure, Pryor was funny—hilarious at times—but if the guy I saw popping his eyes and falling all over himself in California Suite was the funniest man on the planet, then I had to count myself as seriously misguided when it came to what I considered funny. But after resisting the advertisements and the subsequently rapturous reviews in the local papers when the movie opened in Eugene in the spring of 1979, a friend and I caved in and decided to go see what all the fuss was about. We arrived early and sat through the last 10 minutes or so of the apparently awful Redd Foxx/Pearl Bailey comedy Norman, Is That You?, which the Waco Theater had added as a tantalizing enticement toward the end of the Pryor film’s run. (Who would have ever made the decision to come see Richard Pryor Live in Concert based on the knowledge that they could also see Norman, Is That You? was a question I have never adequately felt prepared to ponder.) The first thing my friend and I became aware of, when the lights came up in between shows, was that we were the only whites in the auditorium. Admittedly, this was not a situation with which we were much familiar— being in a racially diverse place like Eugene, attending school at a racially diverse institution like the University of Oregon, seemed a million miles away from the small, almost exclusively white Eastern Oregon desert town where I grew up. I was living a moment that Pryor would expand upon in the movie I was about to see—“Ever notice how nice white people get when there’s a bunch of niggers around?” But when the lights went down and Richard Pryor Live in Concert began, it didn’t take long to feel like I was even further away, unmoored from my preconceptions, my imaginings of the anger and startling immediacy of life lived on the other side of the line in a divided society.

The quote from Lorne Michaels in the ad for Richard Pryor Live in Concert insisted that Pryor was the funniest man on the planet, and try as I might, based on what I’d seen of Pryor up till then, I just couldn’t figure out how this comment could be construed as anything but hype. Sure, Pryor was funny—hilarious at times—but if the guy I saw popping his eyes and falling all over himself in California Suite was the funniest man on the planet, then I had to count myself as seriously misguided when it came to what I considered funny. But after resisting the advertisements and the subsequently rapturous reviews in the local papers when the movie opened in Eugene in the spring of 1979, a friend and I caved in and decided to go see what all the fuss was about. We arrived early and sat through the last 10 minutes or so of the apparently awful Redd Foxx/Pearl Bailey comedy Norman, Is That You?, which the Waco Theater had added as a tantalizing enticement toward the end of the Pryor film’s run. (Who would have ever made the decision to come see Richard Pryor Live in Concert based on the knowledge that they could also see Norman, Is That You? was a question I have never adequately felt prepared to ponder.) The first thing my friend and I became aware of, when the lights came up in between shows, was that we were the only whites in the auditorium. Admittedly, this was not a situation with which we were much familiar— being in a racially diverse place like Eugene, attending school at a racially diverse institution like the University of Oregon, seemed a million miles away from the small, almost exclusively white Eastern Oregon desert town where I grew up. I was living a moment that Pryor would expand upon in the movie I was about to see—“Ever notice how nice white people get when there’s a bunch of niggers around?” But when the lights went down and Richard Pryor Live in Concert began, it didn’t take long to feel like I was even further away, unmoored from my preconceptions, my imaginings of the anger and startling immediacy of life lived on the other side of the line in a divided society.I don’t think I’d ever laughed harder in a movie theater—not even at Blazing Saddles-- and I’m pretty sure that saying I’ve not laughed harder at any movie since is no exaggeration either. Live in Concert was as close to a revelation as I’d ever had involving performance in cinema (or, in this case, cheaply produced videotape transferred to film). The movie is 78 minutes of hard, fast punches, none pulled, none glancing away, delivered with the grace of a prizefighter vessel filled with a level of kinetic, physical acuity and agility that seemed to emanate from, yes, the very soul of Pryor’s tortured, conflicted countenance. The lovely, detailed immediacy with which Pryor conveys the personalities of animals, drug addicts, aged storytellers and, in the movie’s most vivid set piece, his own heart, rebelling against the rest of his body after falling victim to “too… much… pork” (and ingesting too… much… cocaine and tobacco, no doubt), is a rare and exhilarating thing to behold. Seeing Pryor in this movie was, for me, having the missing parts amongst the scattered brilliance of Bicentennial Nigger filled in—what’s missing from the album is the visual electricity of Pryor on the move, gliding across the stage like the most lithe and acutely aware deer in the forest, moving tall and deliberate like the proudest Great Dane in the yard, then humbled and decimated, thrown to the ground in a writhing heap by the twist and crush his overtaxed heart puts on his chest cavity. This sequence is so uncompromising, so hysterically funny, and so vividly enacted, that no matter how many times I see it (and I’ve seen it countless times since that day in the spring of 1979) there comes a point where Pryor’s imagined encounter with his beating, raging heart moves beyond mimicry, moves beyond metaphor, into an area of vivid reality that inevitably brings my own body awareness to such a heightened level that I’m sure, in all seriousness, that I’m on the cusp of a heart attack myself.

Writing in the British newspaper The Guardian in 2004 to commemorate the DVD release of Richard Pryor Live in Concert, writer William Cook said:

“Normally, nothing dates so fast as stand-up, but a quarter of a century after its cinema release, Richard Pryor Live In Concert still retains its power to shock and startle. Indeed, far from playing like a quaint period piece, this landmark performance still feels dangerous and avant-garde.”

A concert film like Eddie Murphy: Raw or The Original Kings of Comedy feels dated almost the minute it’s finished. But Cook is absolutely right—there is nothing about Pryor’s monumental performance in the 1979 release that doesn’t feel as fresh, scabrous and thrilling as it did the day the piece was videotaped. And the difference between Pryor’s art, at its peak, and those who worked in his long shadow for over 30 years, might be best summed up by Jill Nelson in an article she wrote in 1998, upon Pryor’s receiving the Mark Twain Prize for humor at the Kennedy Center that year:

“Most every comedian under 50 has been influenced by Pryor, and not just the black ones. Watching and listening to them, it's as if Pryor's shadow always hovers nearby, revealing itself to varying degrees in inflection, pacing, body language, choice of material… What is most wonderful and most missed about the humor of Richard Pryor is his simultaneous rage and vulnerability -- that sense of being mad as hell yet still yearning for and believing in acceptance and reconciliation, whether he was riffing about black folks, white folks, women, politics, black male macho or drug addiction. For Pryor, humor and talking much shit was a way to reveal not only his, but our collective psyche. In the process he used his voice, body and mind to turn himself into, not them, but us… Richard Pryor is both the best and worst of a time gone but not forgotten, a reflection of our own passions, fears and self-destruction. He may not have died for our sins, but he lived many of them fully, publicly, with gusto. He has suffered the consequences in a no less public way.”

In 1998 Nelson spoke of Pryor in the past tense to indicate the importance of a still-vibrant legacy left by a man then overtaken by the ravages of multiple sclerosis who might never perform again, who might have already given all he would ever give through his particular art. Those words resonate even more strongly in the few hours that have passed since the world learned of the death of Richard Pryor on Saturday, shortly before 8:00 a.m., from a heart attack.

Rest in peace, Richard.

6 comments:

Thank you, Dennis. Rest in peace, indeed, Richard.

xo

Jen

Nice, thoughtful piece on Richard Pryor. I remember when I met you in college, you were quite a fan (more so once you saw the concert movie, I guess), which seemed surprising since you were from a small town, but then your tastes were decidedly sophisticated for a country boy. I, the semi-city boy, couldn't get past his foul mouth and the constant use of the "N" word--but now I think I might like to see that concert film after all!

Thom, Richard or no Richard, Dennis would have married you anyway. You are the light of his life.

Interesting, I'm about the age of the author (I was 16 in 1975). But I grew up at first in Brooklyn, NY and then in the most racially mixed neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio. Additionally, I had been an avid basketball player since boyhood, and hence, had spent quite a bit of time around african-americans my own age. Richard Pryor was funny to me, but I saw nothing extra-ordinary about him or his humor. He took the F-word to the limit, but George Carlin had already taken a stroll down that street.

I've always noticed that whites who were raised in more segregated surroundings often seem to have this need to be "down" with minorities in a way I've never needed to. Black dude telling jokes was just another comedian to me. Cheech and Chong were just as funny, pushed the envelope in much more daring ways regarding drugs, and overall (in the mid 70's at least), made much funnier movies. Granted, they are dated now.

As for Richard Pryor, he had two good albums, a funny concert movie and then he wound up being pretty pathetic (Superman!). I pity him for his drug problems, he never realized his potential, and I pray for his soul. My he rest in peace and happiness.

Anonymous: I know what you mean about some people trying too hard to be "down" with black folk--but believe me, Dennis ain't that guy. More than just about anyone I know, he comes from a place of honest interest in other people; he's not someone who allows himself to operate on stereotypes. I'm sure you're not implying that somebody from a small town shouldn't try to understand or appreciate other cultures, are you? Besides, in my experience people in big cities are just as likely to be prejudiced, or to stereotype others, as they are in small towns--for every person who lives in harmony with his neighbors, seems there's at least one who's brimming with stereotypical ideas and fears about whatever group he's not in.

"I'm about the age of the author (I was 16 in 1975). But I grew up at first in Brooklyn, NY and then in the most racially mixed neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio. Additionally, I had been an avid basketball player since boyhood, and hence, had spent quite a bit of time around african-americans my own age… I've always noticed that whites who were raised in more segregated surroundings often seem to have this need to be 'down' with minorities in a way I've never needed to."

What you term a need to be “down” with minorities (because I wasn’t exposed to much other than white-Irish ranchers where I grew up) I would instead call an interest in seeing the world through another man’s eyes, a man with experiences and points of view sometimes far different, and sometimes not far different at all, from my own. It sounds like you’re suggesting that most white people approach other cultures to which they’ve had little exposure, especially if that approach is through pop culture, in very superficial, self-interested ways. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’d be hard-pressed to imagine that my affection for Richard Pryor, or blaxploitation cinema, or The Autobiography of Malcolm X, or All in the Family, or Roots, gave me some false aura of cool which then elevated my own persona in other people’s eyes back in the ‘70s. (Quite the opposite in many cases, more likely.) If what you’re saying is that, by having the advantage of growing up around people of an ethnic or national origin than your own, integration was always a natural, comfortable state for you, then congratulations. You’re one of the lucky ones. But there’s a world of difference between a white man (or woman) being able to appreciate what a comic artist like Richard Pryor had to offer—and assuming that what there was to appreciate was not off-limits to whites—and someone seeking sympathy and empathy with that culture without regard to true, critical investigation or understanding of it. I value Richard Pryor’s comedic talents highly, I have nothing but respect for the achievements of Martin Luther King, Shirley Chisolm, Charles Burnett, Barbara Jordan, Jackie Robinson and Chuck D., but I have no need to pretend to value hip-hop as an overall style, affect its particular vocal intonations or rhythms, or fall in blindly with Al Sharpton or Jesse Jackson or Spike Lee in order to prove to anyone that I’m 'down' with 'minorities.' Oh, and I shed no tear for Tookie Williams, even as I did for those he killed, and those whom his legacy continues to kill. It’s always a little more complicated than black or white…

"Black dude telling jokes was just another comedian to me. Richard Pryor was funny… but I saw nothing extraordinary about him or his humor. He took the F-word to the limit, but George Carlin had already taken a stroll down that street."

Well, no, there wouldn’t be anything extraordinary about Pryor’s comedy if taking the “F” word to the limit was what he was all about. But I think I described enough of what his comedy meant to me in the above tribute to illustrate that that simply wasn’t the case. As for the suggestion that Pryor was treading a trail first blazed by George Carlin, though the two men were contemporaries, and Carlin’s first comedy album came two years (1966) before Pryor’s (1968), both those initial albums were relatively non-blue, and quite non-indicative of the direction the comedians would take in the ‘70s. And it would be Pryor, with Craps (After Hours) (1971), who would break the TV-friendly Cosby mold first and begin tailoring his material to a raunchier level, and more specifically toward a black audience. Carlin’s influential hit albums FM & AM and Class Clown were both released in 1972.

"Cheech and Chong were just as funny, pushed the envelope in much more daring ways regarding drugs, and overall (in the mid 70's at least), made much funnier movies."

Would listening to Cheech and Chong albums also be considered trying to be “down” with minorities? If so, I guess I’m guilty on this count as well. I was a huge fan of Big Bambu and Los Cochinos in junior high, but by the time Up in Smoke came along I’d lost interest. I will say that both Nice Dreams and Things Are Tough All Over are flat-out hilarious, but Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie and Still Smokin’ are painfully bad. I look forward to seeing Up in Smoke again someday.

"As for Richard Pryor, he had two good albums, a funny concert movie and then he wound up being pretty pathetic (Superman!). I pity him for his drug problems, he never realized his potential, and I pray for his soul."

One of the reasons I kept my comments largely restricted to Richard Pryor Live in Concert is because it is that performance that warrants the bulk of my admiration for what Pryor was able to achieve. I mentioned Silver Streak mainly to illustrate how the movies tried to neuter him right from the start (an image he famously made explicit on his TV show in a response to dealings with network censors). My tribute was never intended as an Entertainment Weekly style overview of his career, but instead a very personal response to the things about Pryor and his career that I felt most passionately about. I honestly didn’t feel like devoting a bunch of space to a filmography that everyone pretty much already knows failed to live up to the potential offered by its star. But I disagree that Pryor never realized his potential, because I think he did exactly that in the stand-up act he perfected in the mid to late ‘70s, as recorded on his albums and, most significantly, by Richard Pryor Live in Concert.

"May he rest in peace and happiness."

Finally, something on which we both can unconditionally agree.

Thanks, Anonymous, for stopping by and for keeping me honest.

Post a Comment