TCM CLASSIC MOVIE FESTIVAL 2013 DAY 1 PT. 2: PULL THE STRINGS! PULL THE STRINGS!

After feeling the slight pull of my eyelids as Marmaduke

Ruggles (Bill, or the Colonel, to his best friend) finally opened the

Anglo-American Grill to the hungry citizenry of Red Gap, Washington, I felt

like a little fortification was in order. My friend, future hall of fame film

archivist Ariel Schudson, had thoughtfully saved me a seat as the crowd filed

in for Ruggles of Red Gap, so after we settled into our seats for

the next feature, I made my way downstairs and brought back a couple of

mid-sized schooners of coffee to help us along on our journey which, after the

great comedy we’d just seen, was still less than halfway accomplished. The caffeine

was a nice insurance policy, but I imagine that what lay ahead of us would have

buzzed us sufficiently all on its own.

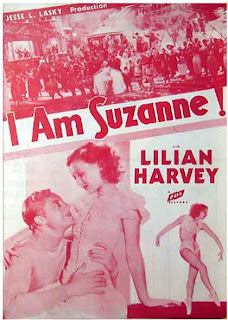

I knew next to nothing about I Am Suzanne! (1933; Rowland V. Lee) as I headed into the tiny

auditorium, but the fascination level spiked almost immediately when Katie

Trainor, archivist for the Museum of Modern Art, introduced the movie and informed

the crowd that what we would be seeing was a fresh “wet” print. It was so fresh that

it had never even been run through a projector for an audience before-- even

Trainor hadn’t seen it. In fact, we would be the first audience to see the

movie projected in 35mm in over 80 years—the only prints in circulation have been

dupes generated from raggedy 16mm copies. How’s that for a set-up? And the

movie lived up to all the precious attendance to its preservation.

I knew next to nothing about I Am Suzanne! (1933; Rowland V. Lee) as I headed into the tiny

auditorium, but the fascination level spiked almost immediately when Katie

Trainor, archivist for the Museum of Modern Art, introduced the movie and informed

the crowd that what we would be seeing was a fresh “wet” print. It was so fresh that

it had never even been run through a projector for an audience before-- even

Trainor hadn’t seen it. In fact, we would be the first audience to see the

movie projected in 35mm in over 80 years—the only prints in circulation have been

dupes generated from raggedy 16mm copies. How’s that for a set-up? And the

movie lived up to all the precious attendance to its preservation.

A follow-up

to their previous collaboration, the atmospheric fairy-tale Zoo in Budapest, the movie reunited Lee

with his cinematographer, Lee Garmes, and lead actor Gene Raymond for another

fanciful story, this one anchored by Raymond and Fox-contracted ingénue Lilian Harvey.

Harvey plays Suzanne, a dancing star who catches the eye of puppeteer/starving

artist Tony Malatini (Raymond), who wants to design a puppet of Suzanne and

build a show around it to bolster the meager attendance of his own company’s

productions. But when Suzanne is injured during a dangerous entrance to an elaborate

production number, he helps Suzanne recover by teaching her how to conduct the

Suzanne marionette herself, and their romance blossoms as Suzanne forges a

union with Tony’s company and has to face the dilemma of whether to continue on

with this new pursuit or return to the perhaps greater popularity awaiting her

if she returns to dance under the guidance of her matronly mentor (Georgia

Caine) and a singularly sleazy and untrustworthy manager (Leslie Banks). Lee and

Garmes give the movie a nimble grace, and the ineffable chemistry between

Raymond and Harvey is considerable, but it’s the movie’s utterly unaffected joy

at performance, its complete belief in and lack of cynicism about the impulse

to entertain, that prove to be the aces up its sleeve. The use of marionette performance works on

several levels too, not least of which for the sheer handmade magic of the

puppeteering itself—the movie conveys a strong sense of the physical demands,

not only of choreography and coordination but also of pure endurance made upon

the performers, and how their joy seems at times literally transmitted through

the strings, into the wooden actors and out into the audience. But it also

resonates metaphorically in very satisfying ways.

Just as exciting, but in a completely different way, was It

Always Rains on Sunday (1948; Robert Hamer). In tandem with I Am Suzanne!, it made for the sort of

thoroughly invigorating revelatory experience that one can only hope for in a

film festival environment of any kind. As introduced by “czar of noir” Eddie

Muller, we were prepared for what has been considered in some circles the quintessential

British noir, and Muller spared no enthusiasm for the movie. But he also drew a

distinction between American noir, with its chiaroscuro roots in German

expressionism and stories of crime and the absence of redemption, and its

British variant, of which It Always Rains

is considered a prime example. Muller observed that British noir tends to

display much more interest in the realities of the country’s underclass, where

crime is an undeniable element in the fabric of the tales told, but not always

the primary focus. This is certainly the case with It Always Rains on Sunday which, as might be guessed from its

title, favors a rich milieu of street-level life, overlapping with noise and

anger, passion and oppression, fear and desire and, yes, the vitality of a

close-knit (or perhaps more accurately, close-pressed) community of postwar citizens,

survivors and hangers-on.

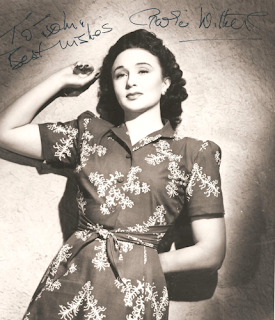

The “plot” concerns the prison escape of a petty

criminal, who hides out in the home of his former lover, Rose Sandigate (Googie

Withers), a woman now married to a decent man who nonetheless feels trapped and

angered by her familial circumstances, which include bumping heads with her

husband’s grown daughters and her own sense of the tight walls of their modest

flat closing in on her. The various vices and distractions of the movie’s single

rainy day swarm and jangle around her, providing the sense of vitality as well

as impending fate, rendered in stunning imagery courtesy of Douglas Slocombe

and Hamer’s expansive directorial sensitivity—Hamer also directed Kind Hearts and Coronets, the blackest

of British comedies, which doesn’t really hint at the sort of richness of mood

and setting and narrative deftness he achieves here. The movie feverishly anticipates the movement of British

kitchen-sink dramas while maintaining the constant surge of dark energy derived

from film noir, and it anticipates as well the skillful, naturalistic weave of

Robert Altman in its approach to telling the stories of its working-class

neighborhood, which spark off each other and contribute mightily to the movie’s

dark, stylized representation of its specific and grim reality.

And then there’s

Googie Withers, a force of nature all her own and completely riveting in her

disappointment and fury and undeniable attraction to the convict (John

McCallum) who will lead her to a downfall as he flees toward his own. The attraction

between the two is palpable on screen in part because it wasn’t faked—Withers and

McCallum met on this film and married soon after, remaining together for the

rest of their lives. But it’s Withers, a critical element in the film’s overall impact, who cannot be ignored. After Night

and the City last year, The Lady

Vanishes and now this one, she must be considered the great anti-heroine of

the TCM Classic Film Festival. As for It

Always Rains on Sunday, its subject may not be exactly uplifting, but the

invigorating charge that radiates from its intense and intricate portrait of an

underclass informed and vitalized by dark currents of petty crime and desire

could never be depressing. After seeing this movie, I couldn’t have been happier.

Next, Ariel and I stuck together and headed off to see Hondo (1953), a western starring John Wayne

that I had never seen. And I probably didn’t put too much urgency behind

pursuing it because of the absence of either John Ford or Howard Hawks in the

credits. Silly me. As it turns out, Hondo

is John Wayne at his most electrifying and, frankly, beautiful—even Leonard

Maltin, who introduced the film, had to admit that Wayne probably never looked

as good, as a purely physical specimen, than he did here. But it’s Wayne’s

performance, as a part-Apache gunman who protects Geraldine Page (in her first

film) and her son from an encroaching Apache onslaught, which was the real

revelation for me. He does the simple things, like a lovely, naturalistic conversation

with Page while shoeing a horse, which few could duplicate with such apparent

ease. But his reactions in the small moments- the look of disbelief that flits

across his face when Page describes him as a gentleman—that are priceless and,

as it turns out, key to the level to which Wayne seems present and alive to his

circumstances in this movie. The persistent myth that John Wayne was a bad

actor or, at the very most an invariant and uninteresting one, is probably one

of the most annoying bits of mythology that still swirls around Hollywood, even

among fans of classic films. This screening certainly helped put to rest any

remaining vestiges of that myth that may have been floating around in my mind.

And oh, yeah, the 3D was fantastic!

But we still had movie #7 for the day to get to. Fortunately

the coffee I gulped eight hours earlier was still working its magic, so we met

up with Richard Harland Smith and made our way into the TCM Underground-sponsored

midnight show, a very rare 35mm presentation, in its proper 1.85:1 aspect

ratio, of Edward D. Wood, Jr.’s Plan Nine from Outer Space (1958).

Richard, in his own piece for TCM, rightly pointed out, with no small amount of

“take that!” satisfaction, that though this movie gained much of its notoriety

from the Golden Turkey phenomenon spearheaded

by Harry and Michael Medved, who dubbed it the worst movie ever made, it’s the

Medved books that now languish in indifference while Ed Wood’s movie is screening

at the TCM Film Festival! That “Worst Movie Ever” moniker has stuck like a

piece of used gum to Wood’s movie, but, as comedian-writer Dana Gould (The Simpsons) pointed out in his

hilarious introduction to the film, it’s one that the movie doesn’t really

deserve. No movie that’s as entertaining as this one, inept as it most

assuredly is, could possibly be the worst ever made. (I offer the somnambulant Lily

Tomlin-John Travolta romance Moment by

Moment as one possible replacement for this dishonor.)

The key to Wood’s “failure”

is, of course, the many well-documented ways in which the movie falls short of

even the basest standards of production value and acting discipline, but lording

it over such an obviously impaired picture on those grounds is really only part

of the fun. As suggested by Tim Burton’s great Ed Wood, what’s fascinating about looking at Plan Nine from Outer Space, especially in a print that probably

looks better than the movie has ever

been seen by even its most snarkily ardent followers, is its sincerity. He may

have been a terrible writer and an insufficient storyteller, but Wood was most

definitely a believer. Even as it builds to its gloriously incoherent climax, I

was hard-pressed to detect so much as a single frame of cynicism in his

demented mise-en-scene. And seeing it at midnight, the capper to a day which

saw six films before it, was the perfect, delirious way to end what I’d wager

was the single greatest day of movie-watching I’ve ever experienced over my

four-year history with the TCM Classic Film Festival, and maybe even of my entire

movie-watching life.

Coming up next, reports on yesterday’s Deliverance experience, plus

They Live by Night, Max von Sydow and

The Seventh Seal, how I joined the

ranks of the cads who walked out on Mildred Pierce, and the story of how I won

my TCM fleece picnic blanket.

But right now, it’s back to Hollywood, where I’ll hit the

road with Gene Hackman, Clark Gable, Al Pacino and Claudette Colbert, and tie a

ribbon on this year’s festival with Grace Kelly, Ray Milland and Alfred

Hitchcock while wearing yet another pair of those stylish 3D glasses. I’ll be

in touch.

******************************************

1 comment:

Big fan of ZOO IN BUDAPEST so I look forward to catching I AM SUZANNE! when it graces MoMA's screen.

Post a Comment