THREE CHILLS TO BEAT THE SUMMER HEAT: ORPHAN, ROGUE and COUNT YORGA, VAMPIRE

You know you’re living in a city where denial of reality and acceptance of the absurd are the main ingredients in the cocktail everyone seems to be sipping when you can, as I did last night, spend 10 minutes watching a crack local TV meteorologist try to convince the audience, herself, and the befuddled anchors nodding at her shtick nearby that the dropping of temperatures from 98 degrees to 92 degrees constitutes a cooling trend that we all oughta be thankful for. Won’t it be great to finally be able to turn off that AC?! We really needed a break after all that heat earlier in the week!

This is, of course, the same tightly-knit, Live Mega Doppler 7000-addicted band of crack TV meteorologists, operating in that same city of absurd denial, that builds whole news hours around the first drop of rain— “Why are you sitting here watching ‘StormWatch 2009’, dear viewer, when you ought to be in your garage stocking survival supplies and building that ark?!”—and attaches animated icicles to numbers on the seven-day forecast when the temps threaten to dip down to 60 degrees.

This is, of course, the same tightly-knit, Live Mega Doppler 7000-addicted band of crack TV meteorologists, operating in that same city of absurd denial, that builds whole news hours around the first drop of rain— “Why are you sitting here watching ‘StormWatch 2009’, dear viewer, when you ought to be in your garage stocking survival supplies and building that ark?!”—and attaches animated icicles to numbers on the seven-day forecast when the temps threaten to dip down to 60 degrees.I wish it weren’t true, but the fact is, there is no real escape from the heat, not when running the AC for three or four hours an evening gets you a several-hundred-dollar monthly electricity bill, and not when you live in a city of sun worshippers presided over by a media for which the myth of an always-temperate and blue-sky-beautiful Southern California is one that must be perpetuated at all costs.

Which is why horror movies are such a good ticket during the summer months—a really good summer screamer, like Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell, can give you the kind of deep-seated chills that go way beyond the cooling of the skin provided by central air. And bless your soon-to-be-rotted soul if you can get your claws on one that happens to be set in a wintry environment, thus inviting the visual component to conspire with the narrative to bring your body temperature down to grave-worthy levels. Movies like The Brood (1979), The Dead Zone (1983)-- David Cronenberg does seem to have a way with the desolate chill of winter-- The Thing (versions 1951 and 1982), the climax of Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), one particularly icy moment involving Lew Ayres from Damien: Omen II (1978), Let the Right One In (2008) and last summer’s woefully underappreciated The X-Files: I Want to Believe (2008) are all excellent examples of how to use a frozen landscape to accentuate and inform a sense of dread and fear.

Some of you may also remember an ABC Movie of the Week entitled A Cold Night’s Death, directed by Jerrold Freeman and starring Robert Culp and Eli Wallach as two scientists air-lifted to a remote Arctic research station who find the facility strangely abandoned, a group of research monkeys in a near-frozen state, and lots of indicators that something has not gone according to plan. This TV-movie occupies a special place in the hearts of many of my generation’s movie genre thrill-seekers, and it’s been famously difficult to find, showing up for the occasional late-night showing when local stations still actually still ran late-show movie programming, but rarely screened since infomercials became the all-nighter’s TV anesthesia of choice. Thankfully, someone has actually posted the entire movie on YouTube, and should you choose to watch this video, you may be in for a viewing that’s even closer to your memory of seeing the movie than you thought possible. I haven’t seen it myself yet, but it looks as though whoever posted this sat in front of an old tube TV screen and shot it with a video camera. The result is an extremely eerie recreation of that staying-up-late-at-night-when-you-were-a-kid frisson of terror that was often part and parcel of catching up with scary movies on TV in the ‘70s. To whoever posted this gem, I thank you profusely, and I forgive in advance anyone who feels they must stop reading this now, shut off all the lights in the room, and make friends with the fuzzy, glowing, intermittently unstable imagery from this posting of A Cold Night’s Death.

But if you decide to continue reading, then feel free to add Jaume Collet-Serra’s spectacularly unnerving Orphan to that short list of superb wintry horror tales. Set in Connecticut during the blustery snowbound months, the movie knows how to exploit that frosty climate—a couple of its more harrowing outdoor set pieces are enhanced by the sense of fear created by the landscape feeling different, less hospitable, less inhabitable, more dangerous. As in those other movies, Orphan cannily externalizes the sense of things not being quite under control by plunging us into this environment so often associated with seasonal joy and familial closeness, where unexpected cracks in the ice can form under our feet, or vehicles can go sailing off slick roads into horrible peril, or toward unaware victims. But the chill in the air surrounding Orphan is only nominally due to its frozen setting. The movie, by means psychological and cinematic, means to put a freeze on your nerves, and that it pretty handily does is a credit to an exceedingly clever script (by David Johnson and Alex Mace) and Collet-Serra’s prodigious talent for throwing the audience’s expectations askew. He does perhaps rely on loud noises and the old "who’s standing behind the refrigerator/medicine cabinet door" trick too much, but so much else about this tale of parental entitlement and fear is so skillfully rendered and low-down effective that I was more than willing to forgive the director these relatively venial sins.

The opening sequence of Orphan will be a very telling indicator of whether you can deal with the shocks the movie has in store. A beatific and pregnant young woman named Kate (Vera Farmiga) is being wheeled into the hospital, her loving husband John (Peter Sarsgaard) by her side, presumably toward the maternity ward where her dreams of becoming a mother are about to come true. The camera hugs the beaming Kate in close-up as a nurse pushes her along, when suddenly we see a look of distress disrupt her glowing face, slowly turning her visage away from joy into a mask of confusion and agony. Kate is obviously in increasingly sharp pain, and yet the nurse never changes the deliberate pace of the wheelchair, never acknowledges the state of her patient except to offer, in a most ghostly, noncommittal tone, “We’re so sorry for your loss, dear.” Loss? Collet-Serra then gives us the first of many sudden shifts in perspective to come, as we see the nurse and patient inching across the wide-screen frame from the point of view of a detached observer from high above, leaving a trail of blood from the abruption occurring inside the woman’s uterine canal along the hospital’s incongruous white shag carpeting. Soon, Kate is strapped to a hospital bed and surrounded with masked surgeons and medical personnel who coolly, callously inform her that she has lost her baby and that an emergency C-section is about to begin. Her screams of denial and horror are met with the happy glance of her husband, himself done up in surgical gown and mask, who continues to aim his video camera at her despite the obviously horrific turn their blissful moment has taken. And he never stops shooting, not even when the nurse pulls a dead, blood-soaked fetus from Kate’s womb and sets it on her chest, a ghastly hello and goodbye rolled into one traumatic moment. At which point Kate screams and wakes up…

Speaking personally, as a father who has witnessed something as horrific, if not as garishly so, as what happens to Kate in her morbidly enhanced nightmare remembrance of profound loss, I had to fight the urge to bolt from the theater during this opening sequence. And had Collet-Serra continued to operate in this weirdly dissociative style of De Palma-tinged surgical theater of horror, who knows how much I could have/would have taken? Fortunately, the director gives us this peek into Kate’s tortured psyche as a way of grounding her psychologically and filling out Farmiga’s choices in playing the character in a way that a simple back story—and everyone here has a back story laced with tragedy—would not do nearly so completely. The movie is not, as one might reasonably expect from the prologue, a grisly freak show a la Takashi Miike, but instead a portrait of how tragedy can unravel even the most perfect-seeming of families and make them vulnerable to outside forces that will personify and exploit the interpersonal instability and mistrust that already exists. During her waking hours Kate, a musician with an alcohol problem who spends her days as a housewife after losing her teaching job at Yale, really is reeling from the stillbirth of a child. She and John, an architect who presumably designed their dazzling postmodern hillside home, channel the reaction to their trauma into a strong desire to adopt. The desperate zeal to patch this hole in their life with an older “sister” to join their two biological children, Daniel (Jimmy Bennett) and Max (a deaf five-year-old played by the remarkable Aryana Engineer), leads them to an orphanage with a none-too-strict policy on background checks. It’s here where they meet Esther (Isabelle Fuhrman, shockingly good), a preternaturally self-possessed nine-year-old Russian girl who dazzles the couple with her artistic ability, her sweet nature, and the pained perspective of the lost child she projects with apparent sincerity, which plays directly into the couple’s savior fantasies of providing for a child in need.

Of course, Esther soon reveals a malevolent side. She orchestrates a playground accident that seriously injures a schoolyard enemy. She puts a bird out of its misery with a rock after Daniel wounds it and cannot bring himself to finish the job. She subtly threatens and emotionally blackmails little Max into assisting her in a series of increasing devilish deeds, at one point pulling a revolver on the guileless child. (“Want to play?” she coolly inquires, removing all but one bullet, spinning the chamber and pointing it at Max’s head. “Perhaps later.”) Something about Esther’s artistic abilities— her mastery of Tchaikovsky on the piano, her increasingly elaborate paintings— also suggests that someone has not provided the whole story on this cinematic descendant of evil little Patty McCormick, and the ones most skillfully holding back on the big picture are the cast and director of Orphan. Truly, if Ms. McCormick was The Bad Seed, there is increasingly little doubt that Esther is the worst.

Of course, Esther soon reveals a malevolent side. She orchestrates a playground accident that seriously injures a schoolyard enemy. She puts a bird out of its misery with a rock after Daniel wounds it and cannot bring himself to finish the job. She subtly threatens and emotionally blackmails little Max into assisting her in a series of increasing devilish deeds, at one point pulling a revolver on the guileless child. (“Want to play?” she coolly inquires, removing all but one bullet, spinning the chamber and pointing it at Max’s head. “Perhaps later.”) Something about Esther’s artistic abilities— her mastery of Tchaikovsky on the piano, her increasingly elaborate paintings— also suggests that someone has not provided the whole story on this cinematic descendant of evil little Patty McCormick, and the ones most skillfully holding back on the big picture are the cast and director of Orphan. Truly, if Ms. McCormick was The Bad Seed, there is increasingly little doubt that Esther is the worst.

If it seems I have spent too much time detailing the roots of the horror Collet-Serra and company have concocted, it’s because to reveal much more would be in violation of the pact this movie makes with its audience to peel back ever-escalating levels of disturbing, psychologically believable behavior by means of a surprising level of horror filmmaking craft. (Stay away from any review that wants to talk about the plot in any kind of detail.) Collet-Serra’s previous horror outing, the Dark Castle productions remake of House of Wax, was a decent effort, marred by a slew of obnoxious stock characters who seemed much more pleasant smothered under molten paraffin. As enjoyable as it was for us, it was apparently a waste of time for him, so much more accomplished is his work here. As I said before, Collet-Serra tends to overdo a certain variety of stock horror movie shocks, but he just as often adds an extra touch—an unexpected camera angle, a beat or two longer for us to twist in the wind before the anticipated jolt arrives with not quite the timing we expected—that enriches the sense of our being guided by someone who has a true knack for harvesting gooseflesh.

It also helps that Orphan features probably the best cast, top to bottom, of any horror movie in recent memory, from familiar faces to rosy-cheeked children who we’ve never seen before. Farmiga, an actress who I frequently find annoying, uses her reputation for portraying ineffectual authority figures (see The Departed) to throw us off the trail of what she has charted out for this character. She plumbs the depths of despair, all right, but there’s an unexpected strength, an exhilarating anger that surfaces in Kate which makes her resistance of Esther, and their ultimate conflict, fraught with multiple, creepy levels of resonance. She also expresses fear and horror extremely well, adding strange physical ticks and vocal hiccups to her flailing about that communicate the character’s disorientation and desperation with frightening, if ironic, assurance. Sarsgaard has a more thankless role, the disbelieving spouse who is so eager to give Esther the benefit of the doubt, against all reason it sometimes seems, that he ends up in the Compromised Position of All Compromised Positions. (How’s that for vague, spoiler hounds?) Even so, he retains a measure of sympathy because he seems genuinely conflicted between his duty to believe his wife and his duty as an adopted father. As mentioned earlier, Bennett and particularly Engineer are excellent child actors asked to go well beyond what one might think someone so young could make believable, and they achieve their goals with brilliance. There’s even room for quality character actors like CCH Pounder as an ill-fated orphanage nun and Margo Martindale, for once not being asked to play white trash, as Kate’s far-too-even-keeled therapist.

But the real praise belongs to Isabelle Fuhrmann, who will, whatever else her career holds in store (and her future does indeed look bright), forever be Esther, a child who harbors depths of foulness far deeper than we will, thanks to the clever screenplay and Fuhrmann’s prepossessed facility as an actress, ever be able to accurately guess. Speaking in a light Russian accent that turns from sing-song to deathly hollow in a twitch, Fuhrmann delivers the goods, drawing us in with misplaced sympathy even when we know we’re one step ahead of the hapless family in the story. The movie invites speculation throughout about Esther’s origins, her motivation, but as it becomes clearer and clearer that Collet-Serra and company have something up their sleeves that is far worse than what we’ve allowed ourselves to imagine, Fuhrmann rises to the occasion with a fury and a camp (as well as vamp) haughtiness that places the movie in the vicinity of one of Brian De Palma’s great sick jokes. Late in the game, when her face grows sallow and sunken and she embarks on the final stages of an inevitable course of execution, the audience realizes, with great shock and giddy satisfaction, that we weren’t as ahead of the game as we thought. Fuhrmann, so young and talented, drives home the movie’s final conceit like a stake in the audience’s collective heart, with the pitch-black glee of an instant icon of horror. All the way home from the theater, it seemed every bus kiosk was lit with her terrifying visage from the movie’s advertising campaign. But it wouldn’t have done any good to close my eyes. Esther, and Orphan, is one for nightmares.

***************************************************

This may come as a surprise (not really-- I just felt like being a smart-ass), but movies set in the sweltering heat can give you chills too. Especially when they’re made with the exceptional craft and sense of fun that Greg Maclean brings to Rogue (2007), a giant crocodile movie set in Australia’s forbidding Northern Territory that fuses the templates of Jaws and Friday the 13th, but ups the ante on the Jason movies by providing us with a cast of potential croc meals that we actually don’t want to see get masticated on screen. Maclean directed the notorious outback slasher pic Wolf Creek (2005), which sports a reputation cruel and gruesome enough to cause me to avoid it thus far. It may be equally well-crafted, but something tells me I can do without another torture wallow at this point. Rogue, however, is vicious, good fun, and it betrays a sly sense of humor right from the start. A cynical travel writer (Michael Vartan) stumbles into an outback bar and grill where the walls are papered with news accounts of grisly croc attacks. He’s waiting for a tour boat to take him up river, and while the friendly clerk behind the counter readies him a cup of tea, he takes a cell phone call from Chicago, which naturally gets peppered with static and drop-outs. “Really bad service here,” Vartan complains to the barely audible colleague on the other end. It’s a complaint the clerk overhears and mistakes for a comment on his demeanor and that of his establishment, which he answers by stirring a dead fly or two into the steaming teacup. This is only the first of many grim jokes the forbidding, bug-infested back country will play on this guy. The movie’s visual strategy is to reveal the beauty of the harsh Northern Country from a distance—the lush cinematography revels in a portrait of lush, untamed, eye-popping wilderness—and contrast it with the brutality of the country seen up close. (Rogue ends on a spectacular shot vaulting up out of the dangerous canyons, a reversal of the movie’s pictorial terms that accentuates the insignificance of its players in such a indifferent environment.)

Vartan eventually finds his boat, populated by an Airport’s-worth of well-drawn character actors, who manage to do much with the meager screen time they’re allotted—among them Caroline Brazier, Stephen Curry and John Jarratt, Wolf Creek’s bloodthirsty killer. They're all piloted by the boat’s tomboyish captain, played by Radha Mitchell with an earthy appeal that has heretofore eluded me in her previous performances, and eventually joined by Mitchell’s roughneck boyfriend, played by up-and-comer Sam Worthington (Terminator: Salvation and James Cameron’s Avatar). The boat is eventually run aground on an island mid-river, and the chilling realization that the river is tidal, meaning that the island will soon be underwater as the hour grows later, puts the characters in a race against time as well as a giant set of choppers which results in excruciating and delicious suspense. Maclean takes a crucial cue from Spielberg in playing coy with the reptile’s big reveal.

The movie is nearly two-thirds complete before we ever get a glimpse of the magnitude of this monster and, even though it is a creature born largely of computer-generated imagery, it is no disappointment. The director is also sly enough to throw us off in terms of anticipating who is next on the croc’s menu, and when. Rogue makes clever use of close-ups and our familiarity with the genre’s conventions to keep us both off balance and intimately tied into the fates of its characters. You may surface at this end of this movie—a straight-to-video treat from the Weinstein’s Dimension label that is so much more satisfying than most of the movies that company successfully brought to theaters over the past few years—amazed at this lean, mean thriller’s ability to breathe life into the most rudimentary of premises. Rogue proudly wears its genre cred on its mosquito-bitten sleeves, amped by the singular thrill that only seeing a man swallowed whole by a eight-meter-long croc, bones crunching and snapping all the way down, can offer. For fans of a good monster movie well-told this is spine, and skull, and leg-cracking good news indeed, mate.

The movie is nearly two-thirds complete before we ever get a glimpse of the magnitude of this monster and, even though it is a creature born largely of computer-generated imagery, it is no disappointment. The director is also sly enough to throw us off in terms of anticipating who is next on the croc’s menu, and when. Rogue makes clever use of close-ups and our familiarity with the genre’s conventions to keep us both off balance and intimately tied into the fates of its characters. You may surface at this end of this movie—a straight-to-video treat from the Weinstein’s Dimension label that is so much more satisfying than most of the movies that company successfully brought to theaters over the past few years—amazed at this lean, mean thriller’s ability to breathe life into the most rudimentary of premises. Rogue proudly wears its genre cred on its mosquito-bitten sleeves, amped by the singular thrill that only seeing a man swallowed whole by a eight-meter-long croc, bones crunching and snapping all the way down, can offer. For fans of a good monster movie well-told this is spine, and skull, and leg-cracking good news indeed, mate. ****************************************************

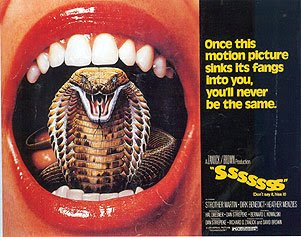

Finally, if it’s still hot here in Los Angeles on August 14, and God knows it most likely will be, you can check out the air-conditioning at the New Beverly Cinema, where an organization by the name of Vampire-Con will be kicking off its festival of All Things Vampire with a mini film festival devoted to cinematic bloodsucking. You’ll be able to see The Lost Boys, Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie in The Hunger, Stephanie Rothman’s exploitation classic The Velvet Vampire, and the one I’m most happy to see back on the big screen, Robert Quarry as Count Yorga, Vampire (1970). American International’s popular foray into vampirism in modern-day Los Angeles, which jumped the gun on Hammer’s Dracula A.D. 1972 by two years, is often crude, and its attempts to exploit its Southern California locations resulted more often in clumsy staging and slack pacing rather than documentary verisimilitude. (And it is a pretty good joke, setting a movie about night-dwelling vampires in the world capital of sun-dappled hedonism.) But the movie, despite its flaws, remains capable of delivering the jolts along with the sly (and not-so-sly) sexuality that was just beginning to be fully exploited by horror films of the time. Count Yorga (Quarry) plays host to a séance conducted in the hopes of contacting the dead mother of a young lady in attendance. Surrounded by her friends (including Michael Murphy in an early role), Yorga hypnotizes the woman ostensibly to reduce her hysterics, but uses the occasion to plan the post-hypnotic suggestion that she become his slave and do as he commands. Of course, Yorga has no good intentions by our heroine, and she soon finds herself, along with a couple of other comely young maidens, part of Yorga’s harem of the undead. When Murphy and a physician friend (played by character actor Roger Perry) discover what’s going on and set their sights on Yorga’s undoing, the movie lurches toward its satisfying finale, which remains somewhat shocking today.

Count Yorga, Vampire was a key movie for me growing up—I saw it when I was about 11 years old, and my taste of horror, while already well-established by the likes of Dark Shadows and the occasional Universal monster movie on Saturday afternoon TV, was just finding its way toward more explicit, bloody fare, as well as more explicitly eroticized takes on vampire lore. (Those scenes featuring Yorga and his slinky minions did a whole lot more than just scare me.) Yorga was an essential stepping stone toward perhaps more vital, solidly imagined tales of terror; it doesn’t have the weight of a real horror classic, but it’s still a lot of fun, even seen through the eyes of someone who has witnessed 38 years worth of horror duds and masterpieces in the interim. Quarry, however, is masterful in a part that I wish could have yielded more than just the one (very good) sequel.

He trades sympathy for sheer animalistic force, upping the ante even on the number of fangs necessary to draw satisfying drink from the neck of his victims, and if his portrait lacks subtlety, it does not lack primal, visceral potency. Seeing Count Yorga, Vampire at the New Beverly will undoubtedly provide goose bumps of different varieties—the ones generated by a good horror show, to be sure, but also, for me, ones brought on by the revisiting of a key movie in my development as a true believer in all the famous monsters of filmland, one that hinted at the many possibilities I would soon discover within the telling of stories in this most mutable and flexible of genres. That chill in the air on August 14 might be the New Beverly’s air-conditioning—I hope it will be—but I look forward to allowing myself to imagine that it might also be the damp chill of the catacombs beneath Castle Yorga.

He trades sympathy for sheer animalistic force, upping the ante even on the number of fangs necessary to draw satisfying drink from the neck of his victims, and if his portrait lacks subtlety, it does not lack primal, visceral potency. Seeing Count Yorga, Vampire at the New Beverly will undoubtedly provide goose bumps of different varieties—the ones generated by a good horror show, to be sure, but also, for me, ones brought on by the revisiting of a key movie in my development as a true believer in all the famous monsters of filmland, one that hinted at the many possibilities I would soon discover within the telling of stories in this most mutable and flexible of genres. That chill in the air on August 14 might be the New Beverly’s air-conditioning—I hope it will be—but I look forward to allowing myself to imagine that it might also be the damp chill of the catacombs beneath Castle Yorga. ********************************************************