THE UNUSUAL SUSPECTS: 13 UNDERRATED, IGNORED OR FORGOTTEN HORROR MOVIES

“Round up the usual suspects.” – Claude Rains, Casablanca

“Supernatural, perhaps. Baloney, perhaps not.”- Bela Lugosi, The Black Cat

************************************************************************************

Almost as much as at the end of the year, Halloween is a time of the year when everybody—critics, feature writers, filmmakers, sometimes even the average filmgoer—loves to trot out their lists. The Best Horror Movies Ever Made. The Scariest Horror Movies Ever Made. My Favorite Horror Movies of All Time. Lists like these are usually fun to read, because they can often serve as a good insight into how the writer thinks, and they can be a good jumping-off point for compiling your own list of titles to rent or otherwise seek out that you may have never seen, or even heard of before.

The only problem is that many of these lists, especially the ones that show up in the big national magazines or on cable TV as special Halloween features, end up looking an awful lot alike—it’s not unreasonable to imagine a huge percentage of those considering a compendium of favorite or best horror movies finding room for Psycho, The Exorcist, The Bride of Frankenstein, Night of the Living Dead, The Shining, Rosemary’s Baby, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Suspiria or, of course, Halloween on their lists.

Which is perfectly fine, because any list of “Best” or “Favorite” horror films probably should include several, if not all, of those titles (at least three of them appear on my own attempt to wrangle my favorites list down to a manageable length.)

This year, however, I decided a different tack might be more fun. Most lovers of film enjoy being directed toward a title they’d never heard of before, or one they assumed was terrible because of all the negative reviews, only to find out it held a special appeal for them despite its reputation, once they finally saw it. And horror film lovers, a group with more of a proclivity toward jaded seen-it-all attitude than fans of any other genre, get genuinely excited when a horror or suspense film, especially a disregarded or unfamiliar one, manages to cut through all their defenses and squirm under their skin, or work unexpectedly on a metaphorical level, to reveal itself to be more than an effective shriek machine.

So here then, with a tip of the hat toward and all due respect for the films mentioned above (and the 400-500 other ones you’ll probably think of that were somehow left out of this admittedly limited discussion), is my attempt to guide the discerning horror film aficionado, as well as the average viewer in search of a good movie, whatever the genre, toward some favorite titles that haven’t really seen their share of the limelight over the years. Devoted cinephiles and students of horror will undoubtedly be at least familiar with most of the movies on this list, and some will seem considerably more high-profile than would appear to be appropriate for consideration here. Interesting too is the fact that, with three notable exceptions, none of the films on my list were directed by auteurs of the genre, but instead by first-time directors or filmmakers not usually associated with horror. The point, however, is not to compile as exclusionary a roster of hard-to-find fright esoterica as possible, or films with unimpeachable pedigrees. The simple point is to shine that limelight once again on 13 titles, some more well-known than others, none of them likely to be first choices to occupy a “Best” or “Favorites” list along with The Exorcist or Halloween, and few likely to be the same as any given reader might choose for his or her own list. This is my not-at-all-scientifically compiled line-up of 13 Underrated, Ignored or Forgotten Horror Movies, in alphabetical order:

A BAY OF BLOOD (Twitch of the Death Nerve) (1971; Mario Bava)

A BAY OF BLOOD (Twitch of the Death Nerve) (1971; Mario Bava)Perhaps the apex of Bava’s many visually stylish horror thrillers, A Bay of Blood opens with the sound of a fly buzzing around the edges of a beautiful lake, the bloody bay of the title. Suddenly, the fly either runs into the water by accident or drops dead into it, with a visible and audible plunk. So it will go for the various characters hovering around a lakeside property, players and hangers-on in a real-estate dispute set off by the murder of an elderly, wheelchair-bound woman, the estate’s wealthy owner. Bava plays with our expectations right from the start, revealing the identity of the woman’s murderer, only to have him quickly extinguished as well. Other suspects become victims too through various gory means, as Bava turns pulling the rug out from under his audience into a terrifying game of which he is the undisputed master. If that remote lake setting and the slow dispatching of victims by a mysterious killer sounds familiar, it should-- A Bay of Blood is said to be the seminal influence (another way of saying “ripped-off source material”) on Friday the 13th. When you come to the scene in Bay when two lovers are skewered on a pole, the bloody spear entering the man’s back and exiting out the bottom of the mattress, there’s no more doubt as to the veracity of that claim. The Friday the 13th series aped the setup and the extreme gore of A Bay of Blood (which contains violence that is still shocking nearly 40 years after its release), but Sean Cunningham et al had no idea how to emulate what makes Bava’s film compelling and notable—the director’s brilliant command of visual style and storytelling. Even when his movie lapses into a comparatively limp conclusion that takes its narrative strategies one step too far, A Bay of Blood remains a potent shocker, miles ahead of the movies that would make so much money, and start a downslide for horror movies that would stretch over two decades, by cynically appropriating the surface elements of Bava’s work and eviscerating the movie’s steaming guts, leaving them to cool by the side of Crystal Lake, just out of frame.

BLACK CHRISTMAS (1975; Bob Clark)

BLACK CHRISTMAS (1975; Bob Clark)Like A Bay of Blood was to Friday the 13th, Bob Clark’s holiday-themed slasher film was an admitted influence on John Carpenter, and it predates Halloween by three years. But many of the genre’s familiar visual motifs are present here, including long periods of foreboding silence and an early stab at Steadicam-type camera movement to suggest the killer’s point of view. (In an interview, Clark admitted that the movements were done sans Steadicam, with a camera mounted on the operator’s head.) Black Christmas, a slasher thriller taking the form of a whodunit set on a small college campus, features a pretty good cast, including Olivia Hussey, Keir Dullea, John Saxon and Margot Kidder, who steals the movie outright as one of Hussey’s foul-mouthed sorority sisters who engages the killer in a memorable trash-talking phone call. (It was Kidder, in this film, who introduced me, at age 15, to the word “fellatio.”)

Clark does a fine job teasing the audience with the various possibilities as to the killer’s identity. But where Halloween offers a creditable back story for the knife-wielding Michael Meyers, Clark and company offer no such comfort, either at the beginning or the end of the film, leaving the audience chilled in a way that goes far beyond the movie’s wintry setting. And Black Christmas registers at least one grisly image into the horror hall of fame—that screaming woman in the rocking chair, her gasping visage wrapped in plastic, a human Christmas present from the movie’s relentless psycho to the rest of the terrorized sorority sisters and, of course, to us.

Clark does a fine job teasing the audience with the various possibilities as to the killer’s identity. But where Halloween offers a creditable back story for the knife-wielding Michael Meyers, Clark and company offer no such comfort, either at the beginning or the end of the film, leaving the audience chilled in a way that goes far beyond the movie’s wintry setting. And Black Christmas registers at least one grisly image into the horror hall of fame—that screaming woman in the rocking chair, her gasping visage wrapped in plastic, a human Christmas present from the movie’s relentless psycho to the rest of the terrorized sorority sisters and, of course, to us. CALVAIRE (The Ordeal) (2005; Fabrice Du Welz)

CALVAIRE (The Ordeal) (2005; Fabrice Du Welz)A lounge singer who makes his living touring old-age retirement homes (where the nurses and the infirm female residents are sexually infatuated with him) is headed for his next stop when his van breaks down in a dark forest. The man who stumbles on him, ostensibly offering help, is wandering the woods at night searching for his beloved dog, and even after he leads the singer to lodging for the night, despite the late hour he heads back out into the dark, distraught, calling his dog’s name. We’ve seen enough of these kinds of scenarios in horror films to know this is not a good sign. The singer is taken in by the friendly proprietor of an empty hotel, a ex-comedian who goes by the name of Bartel, and it is not long before we discover (as does the singer) that there is a very dark current flowing underneath Bartel’s accommodating manner. By the time we notice, printed on a certificate on the hotel wall, that Bartel’s first name is Paul, we have already noted quotes from Deliverance and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in this sublimely creepy Belgian thriller, and the quotes don’t stop there. But they are deliciously warped by director Du Welz into a perverse meditation on the delusions of obsession, and the lengths to which a man can go to ensure the objects of his obsessions stay securely under his control. Calvaire is grim stuff, but despite its English title, it’s not an ordeal to sit through, like Wolf Creek or High Tension or even the comparatively toothless Hostel. The director leavens the crucifixions and various humiliations with inexplicable humor, even as he turns the screws (or drives in the nails). It would be wrong to reveal the direction this movie swerves toward—just know that it’s not the one that such a plot setup might suggest, and if the feeling the movie leaves you with is ambivalent, and maybe even a little plaintive, Du Welz would likely be amused and satisfied that he’s done well indeed.

CRONOS (1992; Guillermo del Toro)

CRONOS (1992; Guillermo del Toro)On the eve of the general release of Pan’s Labyrinth, which has been received with glowing reviews all up and down the festival circuit, it’s nice to revisit Guillermo del Toro’s first feature and realize how assured and unusual it still is. Cronos begins with the chronicling of the history of a 16th-century alchemist’s attempts to merge technology with magic and metaphysics in the creation of the Cronos Device, a palm-sized contraption that holds within it the ability to make whoever uses it immortal. When the device is discovered by the kindly owner of an antique shop (Federico Luppi) and his mute granddaughter, he unwittingly activates it and discovers that the immortality bestowed on him is of a distinctly vampiric quality—sensitivity to light, a desire to consume blood. He must try to control his ever-changing body and its appetites while keeping the device from falling into the hands of a demented billionaire (Claudio Brook) and his even more demented son (Ron Perlman).

Del Toro’s scenario sounds like one that would be ripe for comedy, and Cronos does have its humorous, oddball touches, but they are not in any way self-conscious. Instead, they are woven into a film with a texture that is uniquely its own. The trajectory of the grandfather’s inevitable fate is at times darkly funny, but he’s always a figure of respect and compassion, even as he licks blood off of a bathroom floor. And the whole movie has an awareness of mortality that comes from the man’s realization that he is no longer bound by it, but it’s not an awareness characterized by exhilaration—he doesn’t want to continue on in a world where all that he loves, particularly his granddaughter, will have been left behind. Cronos is rooted in exploitation horror, but Del Toro imbues it with a surprisingly mournful quality and a contemplative pace that rebuffs the shock-and-awe relentlessness that would come to characterize other horror films of the period, including his own Blade 2.

Del Toro’s scenario sounds like one that would be ripe for comedy, and Cronos does have its humorous, oddball touches, but they are not in any way self-conscious. Instead, they are woven into a film with a texture that is uniquely its own. The trajectory of the grandfather’s inevitable fate is at times darkly funny, but he’s always a figure of respect and compassion, even as he licks blood off of a bathroom floor. And the whole movie has an awareness of mortality that comes from the man’s realization that he is no longer bound by it, but it’s not an awareness characterized by exhilaration—he doesn’t want to continue on in a world where all that he loves, particularly his granddaughter, will have been left behind. Cronos is rooted in exploitation horror, but Del Toro imbues it with a surprisingly mournful quality and a contemplative pace that rebuffs the shock-and-awe relentlessness that would come to characterize other horror films of the period, including his own Blade 2.  HELLBENT (2005; Paul Etheredge-Ouzts)

HELLBENT (2005; Paul Etheredge-Ouzts)When I saw the trailer for HellBent, I have to admit it looked insufferable—an unholy coupling of earnest gay indie, shot on digital video, with cliché-ridden slasher formula-- Jason Takes West Hollywood. But other than replacing Jamie Lee Curtis, P.J. Soles and Nancy Travis with a quartet of good-looking (gay) guys getting in costume for a raucous Halloween night celebration on Santa Monica Boulevard, HellBent (what a great title!) has nothing on its mind other than creepy fun, and that’s a good thing. The fellas spy a well-cut hulk in a devil’s mask on their way to the big party and throw some taunts his way. Unfortunately, they don’t know that earlier in the evening this silent giant beheaded two other gay men in flagrante delicto, and now he will spend the rest of the night hunting them down one by one amidst the thumping beats and flashing lights and wild costumed revelers that make up the delirious Halloween street scene. In many respects, HellBent gets by with a lot of mid-level acting and less-than-graceful plotting simply on the juice created by the juxtaposition of a gay sensibility upon a worn-thin genre concept.

But along the way it also flaunts a couple of virtuoso set pieces-- including a murder on a crowded dance floor under stroboscopic lights, where the victim grasps his fate, and glimpses of his murderer, in disorienting shards of light and fragments of time-- and makes its way nimbly to a very effective take on the typical slasher-film climax. Even that knife-on-eyeball imagery, which struck me as excessive and absurd when I saw it in the ads, turns out to be the source of a good twist and some tension-relieving laughter. And in a strange sort of way, perhaps because of its nonpoliticized point of reference, HellBent acts as a corrective to a film like Cruising, which came uncomfortably close to grooving on the agonies dished out to its gay-bar dwelling victims. In this movie’s world, gay men aren’t killed because they inadvertently give a sexually conflicted killer a hard-on, but because they’re a legitimate part of a community and as such are fair game for the random violence of a cinematic psycho whose motives remain, as is the fashion, masked, a psycho who could, as far as this movie is concerned, be gay himself.

But along the way it also flaunts a couple of virtuoso set pieces-- including a murder on a crowded dance floor under stroboscopic lights, where the victim grasps his fate, and glimpses of his murderer, in disorienting shards of light and fragments of time-- and makes its way nimbly to a very effective take on the typical slasher-film climax. Even that knife-on-eyeball imagery, which struck me as excessive and absurd when I saw it in the ads, turns out to be the source of a good twist and some tension-relieving laughter. And in a strange sort of way, perhaps because of its nonpoliticized point of reference, HellBent acts as a corrective to a film like Cruising, which came uncomfortably close to grooving on the agonies dished out to its gay-bar dwelling victims. In this movie’s world, gay men aren’t killed because they inadvertently give a sexually conflicted killer a hard-on, but because they’re a legitimate part of a community and as such are fair game for the random violence of a cinematic psycho whose motives remain, as is the fashion, masked, a psycho who could, as far as this movie is concerned, be gay himself.  ISLAND OF LOST SOULS (1933; Erle C. Kenton)

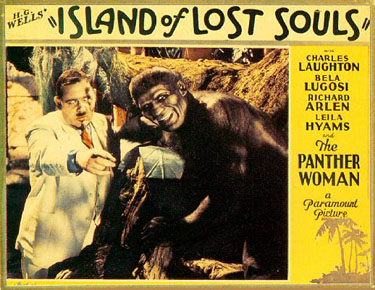

ISLAND OF LOST SOULS (1933; Erle C. Kenton)“Do you know what it means to feel like God?” asks the delusional, ghoulish and exquisitely condescending Dr. Moreau (Charles Laughton) of Edward Parker (Richard Arlen), a sailor held prisoner on a remote island where the mad doctor conducts experiments in cross-matching human subjects with animals in the name of knowledge and his own delusions of grandeur. The other versions of H.G.Wells’ classic tale of horror have asked the same question, and they’ve run the gamut from well-mounted (Don Taylor’s The Island of Dr. Moreau, starring Burt Lancaster) to disastrous (John Frankenheimer’s The Island of Dr. Moreau, starring Marlon Brando). But none have matched this 1933 version for foreboding atmosphere, heartrending pathos and grandeur of another sort, the kind embodied by Laughton in his brilliant, comically insinuating, oft-parodied turn as the Man Who Would Be Creator. Director Kenton, who would go on to direct the equally atmospheric The Wolfman for Universal seven years later, teases out a mounting dread as Parker begins to understand the scale of Moreau’s abominations, evolutionary monstrosities fully realized within Moreau’s laboratory, the House of Pain.

Kenton and his cast hit exactly the right notes of the slowly dawning horror that accompanies awareness, too, in the climactic scenes which see half man-half beast Bela Lugosi leading his fellow victims in murderous revolt (“Are we not men?!”) against his creator’s vile and humiliating oppression. (“What is the law?!”) But the movie lives and breathes in the nuances that Laughton is able to fold into his celebrated and imposing characterization, itself a cross-pollination of the grandiosity of fully cured ham, targeted to the rafters, and the quiet observation of a man crumbling under his own smothering sense of failed destiny. This sensational, horrifying and surprisingly painful movie, as strong and important a part of the Universal horror cycle as Frankenstein, Dracula or The Invisible Man, deserves to be rediscovered and celebrated all over again with a proper restoration on DVD.

Kenton and his cast hit exactly the right notes of the slowly dawning horror that accompanies awareness, too, in the climactic scenes which see half man-half beast Bela Lugosi leading his fellow victims in murderous revolt (“Are we not men?!”) against his creator’s vile and humiliating oppression. (“What is the law?!”) But the movie lives and breathes in the nuances that Laughton is able to fold into his celebrated and imposing characterization, itself a cross-pollination of the grandiosity of fully cured ham, targeted to the rafters, and the quiet observation of a man crumbling under his own smothering sense of failed destiny. This sensational, horrifying and surprisingly painful movie, as strong and important a part of the Universal horror cycle as Frankenstein, Dracula or The Invisible Man, deserves to be rediscovered and celebrated all over again with a proper restoration on DVD.  THE OMEN 666 (2006; John Moore)

THE OMEN 666 (2006; John Moore)There are sequels, and then there are remakes—not a new phenomenon, certainly, and not even an automatic kiss of death artistically speaking (John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) was a remake of a 1931 version which had already been redone once, as Satan Met a Lady (1936), and His Girl Friday(1940) was a rethinking of The Front Page (1931), and both versions would be remade, in 1974 and 1988, respectively). But in 21st-century Hollywood remakes are increasingly commonplace, especially remakes of venerated, and not-so-venerated, horror classics (Black Christmas is getting a new coat of paint this coming holiday season.)

So news of a very faithful remake of Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976), itself sequelized three times, didn’t exactly set my heart a-racing. But only about 15 minutes into the new version, directed by John Moore (whose last movie was another good remake, The Flight of the Phoenix), I had to admit I liked it, and The Omen 666 held me tight within its grasp, even though I was already so familiar with the story it was telling. Perhaps because I was. The Omen 666 has a definite faithfulness to the original-- David Seltzer, writer of the original film, is the sole credited writer, even though his screenplay has been retrofitted in spots to acknowledge some very real 21st-century horrors—but Moore directs with a strong sense of vitality and visual imagination without the requisite overcutting. The man knows the value of holding a shot, as well as juxtaposing those sustained shots with shock cuts that arrive a beat or two off of what the viewer expects, and he directs as if the story were fresh out of the box, with an eye toward upending expectations for some very familiar set pieces. A friend who, besides me and my best friend, is the only other person I know who liked this movie, likens it to a really good cover version of a classic rock tune, which has been tweaked and twisted in enough places to impress fans of the original and yet stand on its own. And The Omen 666 definitely stands on its own. With all due respect to the original, I think it’s the better, tighter, scarier and better acted film of the two.

So news of a very faithful remake of Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976), itself sequelized three times, didn’t exactly set my heart a-racing. But only about 15 minutes into the new version, directed by John Moore (whose last movie was another good remake, The Flight of the Phoenix), I had to admit I liked it, and The Omen 666 held me tight within its grasp, even though I was already so familiar with the story it was telling. Perhaps because I was. The Omen 666 has a definite faithfulness to the original-- David Seltzer, writer of the original film, is the sole credited writer, even though his screenplay has been retrofitted in spots to acknowledge some very real 21st-century horrors—but Moore directs with a strong sense of vitality and visual imagination without the requisite overcutting. The man knows the value of holding a shot, as well as juxtaposing those sustained shots with shock cuts that arrive a beat or two off of what the viewer expects, and he directs as if the story were fresh out of the box, with an eye toward upending expectations for some very familiar set pieces. A friend who, besides me and my best friend, is the only other person I know who liked this movie, likens it to a really good cover version of a classic rock tune, which has been tweaked and twisted in enough places to impress fans of the original and yet stand on its own. And The Omen 666 definitely stands on its own. With all due respect to the original, I think it’s the better, tighter, scarier and better acted film of the two. Liev Schreiber takes the longest to warm up to—Gregory Peck casts an awfully long, authoritative shadow, after all— but he comes through with his own conviction as the satanic plot moves forward. Julia Stiles, on the other hand, is a definite improvement over Lee Remick—her empathetic, powerful performance is the movie’s real revelation (and the movie definitely improves upon the circumstances of her demise from the original, making it far more moving and agonizing). Mia Farrow takes the character of Miss Baylock, she of Satan’s nanny service, in a slightly different, passive-aggressive, almost sexualized direction, than Billie Whitelaw’s more overtly evil incarnation, but she too is, if not an improvement, then at least an interesting addition. And little Seamus Davey Fitzpatrick might be considered a more intimidating presence as Damien than was Harvey Stephens, who shows up here as a TV reporter. I’ve talked to a lot of people who claim everything from disdain to outright hatred for this new version of The Omen, but I can never get anyone to be specific about what exactly it is that supposedly “sucks” about it. I can only conclude that it’s the idea of another remake that’s being dismissed. I too was ready to laugh and roll my eyes at The Omen 666, but this is no cynical rehash-- its dexterity and intensity as a piece of filmmaking is mightily convincing, and it provides more evidence that director John Moore is a sharp talent worth keeping a close eye on.

Liev Schreiber takes the longest to warm up to—Gregory Peck casts an awfully long, authoritative shadow, after all— but he comes through with his own conviction as the satanic plot moves forward. Julia Stiles, on the other hand, is a definite improvement over Lee Remick—her empathetic, powerful performance is the movie’s real revelation (and the movie definitely improves upon the circumstances of her demise from the original, making it far more moving and agonizing). Mia Farrow takes the character of Miss Baylock, she of Satan’s nanny service, in a slightly different, passive-aggressive, almost sexualized direction, than Billie Whitelaw’s more overtly evil incarnation, but she too is, if not an improvement, then at least an interesting addition. And little Seamus Davey Fitzpatrick might be considered a more intimidating presence as Damien than was Harvey Stephens, who shows up here as a TV reporter. I’ve talked to a lot of people who claim everything from disdain to outright hatred for this new version of The Omen, but I can never get anyone to be specific about what exactly it is that supposedly “sucks” about it. I can only conclude that it’s the idea of another remake that’s being dismissed. I too was ready to laugh and roll my eyes at The Omen 666, but this is no cynical rehash-- its dexterity and intensity as a piece of filmmaking is mightily convincing, and it provides more evidence that director John Moore is a sharp talent worth keeping a close eye on. THE OTHER (1972; Robert Mulligan)

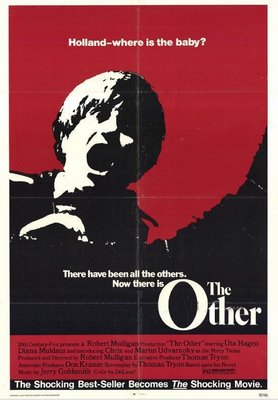

THE OTHER (1972; Robert Mulligan)It had been years seen I’d seen this eerie rural gothic, but after having seen it again, upon its recent DVD release, I’m mystified as to why The Other hasn’t been hailed as an out-and-out classic. As it stands, not many people under the age of 30 have even heard of it. Based on the Thomas Tryon best-seller (and adapted by Tryon for the screen), The Other unravels like a ghost story version of To Kill a Mockingbird, one in which Atticus Finch has gone a wee bit crazy after the death of his wife, and Scout or Jem harbor a terrible secret. (Mulligan directed both films.) Twins Niles and Holland Perry (Chris and Martin Udvarnoky) frolic for the summer on their parents’ farm, supervised by aunts, uncles, a cousin and his pregnant wife, and their doting Russian grandmother (Uta Hagen), but despite the idyll there is an undercurrent of darkness underlying their play. The movie takes place in the early ‘30s and awareness of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping hangs in the air (one of the boys has even drawn a picture of Bruno Hauptmann which hangs on their bedroom wall). In fact, haunting images of children in peril, and how we deal with the loss of loved ones, are central to the movie’s themes. In the first hour, the grandmother, speaking to Niles, explains that “God does not mean that we should miss too much what he takes from us.” But it’s the characters’ inability to move on from devastating loss that forms the tragic heart of this eerie tale, and by the time the film has dropped its big shock on us—about 45 minutes earlier than M. Night Shamaylan would have—The Other has become just as much about how the dead can hold onto the living and refuse to let go. What’s riveting about the way the movie’s secret is revealed is that it is only part of the story—the rest of the movie tells a captivating, and increasingly agonizing, tale about what one of the boys does in the shadow of the reality his grandmother forces him to confront. And a second viewing reveals that Mulligan and Tryon have told the audience everything they need to know about that secret from the very first shot, but they do it in such a way that never calls attention to itself, either as a storytelling or a visual gimmick. Only in retrospect does it become painfully obvious what has been happening from the beginning; credit the writer and director for coming up with an engrossing tale that wraps us up too tight in its web to ever let us get too distracted and start looking for “clues.”

(One last observation directed at those who have seen the movie recently on DVD and may have memories of it from its theatrical run: one of the film’s opening shots gives us our first glimpse of Niles, sitting alone in the woods, waiting for his brother Holland, who can be heard whistling in the distance. As Niles sits there, the camera moves in from a medium long shot to a tighter medium shot, and perhaps even closer, and when I saw the film again last night there was a definite “ghosting” effect around the little boy, making it look like a double of his image was laid on top and slightly askew, creating the effect of two boys superimposed on each other. But the shot was not one composed through opticals, nor was any other shot in the movie marred by what I assumed at first to be an accidental bit of video artifacting. However, it’s so subtle, and works so directly as a thematic link to what the movie will be getting up to, that if it were intentional I wouldn’t be surprised. Does anyone recall this “ghosting” being in the original theatrical prints? And what do you see when you look at the DVD in the scene? Is it a goof-up in the DVD mastering, or are Mulligan and Tryon being clever from the get-go?)

THE PLAGUE OF THE ZOMBIES (1966; John Gilling)

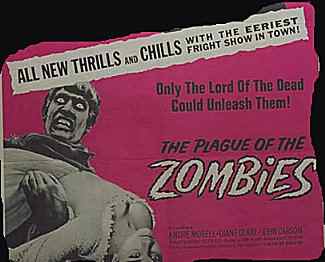

THE PLAGUE OF THE ZOMBIES (1966; John Gilling)Hammer Films, the London-based company that dominated British horror films in the 1950s and 1960s, had a marvelous run with Frankenstein and Dracula and Dr. Quatermass, as well as other one-off thrillers, but their one and only foray into zombie territory is also one of their very best efforts. Luridly, lushy photographed even by Hammer standards, Plague follows the attempt of a London doctor (Andre Morell), in Cornwall at the behest of a former student, to discover the cause of a series of perplexing deaths, a mission made more difficult by the refusal of the bereaved families to allow any autopsies. Director John Gilling (The Reptile) does a great job of foreshadowing the real cause behind the deaths when he stages a solemn funeral that coincides with the arrival in town of the doctor and his comely daughter, a funeral which is interrupted by a rough encounter with a band of fox hunters who show no remorse at causing the body to tumble out of its coffin onto the street. Without being too explicit about the mystery behind the imminent horrors the movie chronicles, it turns out that a strange voodoo cult, led by a local squire/coroner/magistrate, has plans for turning useless corpses into a force of the undead that will have a much more practical purpose. With minimal fuss and lots of visual style, the stage is set for a superbly insinuating atmosphere of waking nightmares as the squire’s plan is slowly revealed—the day-for-night image of a woman stumbling upon a zombie in the midst of stealing away a soon-to-be-undead corpse is an image that has been burned in my mind since I first saw it as a young boy, and it retains its power to shock, even in this post-Romero age.

Plague of the Zombies works as a horror film and as a rare pass, for Hammer, at social critique as well, an allegorical and unrelenting indictment of the British class system, and such reveals itself to be a textbook case for how the horror film can be employed in myriad ways beyond simple scream production. (I wonder if George Romero has ever cited this movie as an influence on his own zombie cycle.) The movie’s force dissipates slightly as it lurches toward its conclusion, but the effect is not debilitating. This is a gorgeous, seductive, well-constructed thriller that has stood the test of time better than almost any other of its kind.

Plague of the Zombies works as a horror film and as a rare pass, for Hammer, at social critique as well, an allegorical and unrelenting indictment of the British class system, and such reveals itself to be a textbook case for how the horror film can be employed in myriad ways beyond simple scream production. (I wonder if George Romero has ever cited this movie as an influence on his own zombie cycle.) The movie’s force dissipates slightly as it lurches toward its conclusion, but the effect is not debilitating. This is a gorgeous, seductive, well-constructed thriller that has stood the test of time better than almost any other of its kind. RAVENOUS (1999; Antonia Bird)

RAVENOUS (1999; Antonia Bird)It’s forever fascinating to me how some of the best horror films are ones that were either dumped by their studio or the recipient of catastrophic, condescending reviews that seem to suggest a moral transgression implicit in their ever having dealt with their particular subject matter at all. It happened with Night of the Living Dead. It happened with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And it happened to Ravenous, directed by Antonia Bird, who hasn’t made a movie since this one was released. Interesting too that all three, on some level, deal with cannibalism, and deal with it as political or social allegory. Guy Pearce is a soldier in the Mexican-American war who, despite single-handedly capturing a Mexican outpost, is discovered to have pretended to be dead, pulling corpses over himself in order to hide during the heat of battle. His commanding officer is disgusted by this display of cowardice and assigns him to a remote mountain fort in the Western Sierra Nevadas of California. Soon, he and the other officers there (a great cast including Stephen Spinnella, Jeffrey Jones and Neil McDonough) are set upon by Colquhoun (Robert Carlyle), who stumbles out of the woods with a story of being possibly the only survivor of a downed traveling party who may have succumbed to the survival-inspired appetites of the Army colonel leading their group. It is soon revealed that Colquhoun himself is that cannibal officer, who has his eyes on either changing the officers to his meat-eating ways or consuming them, thus taking over the fort and continuing to victimize unsuspecting pioneer travelers who pass through the post on their way West.

Ravenous is steeped in viscera and red, red blood—like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, it might have been made by a militant vegetarian. And it is set to genuine odd rhythms, alternating low comedy with ghastly horror and unbearable suspense, augmented by the high-spirited fiddles and thrumming undertones of a disorienting score by Michael Nyman and Damon Albarn (of the British pop groups Blur and Gorillaz). It’s also viciously, hilariously literal-minded about American manifest destiny, linking the military that swept westward in the mid-1800s, subsuming whole cultures and geography and property under its hooves and wheels and tracks, with a military officer who sees his own destiny, and that of the country he represents, in quite literally consuming his/our way toward domestic and geopolitical dominance. In Ravenous, nothing is truer than that old bromide, slightly twisted: we are who we eat.

Ravenous is steeped in viscera and red, red blood—like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, it might have been made by a militant vegetarian. And it is set to genuine odd rhythms, alternating low comedy with ghastly horror and unbearable suspense, augmented by the high-spirited fiddles and thrumming undertones of a disorienting score by Michael Nyman and Damon Albarn (of the British pop groups Blur and Gorillaz). It’s also viciously, hilariously literal-minded about American manifest destiny, linking the military that swept westward in the mid-1800s, subsuming whole cultures and geography and property under its hooves and wheels and tracks, with a military officer who sees his own destiny, and that of the country he represents, in quite literally consuming his/our way toward domestic and geopolitical dominance. In Ravenous, nothing is truer than that old bromide, slightly twisted: we are who we eat. RAW MEAT (1972; Gary Sherman)

RAW MEAT (1972; Gary Sherman)Speaking of cannibalism, the second movie on this list to deal with the forbidden practice is director Gary Sherman’s nearly forgotten minor masterpiece. Sherman’s career never amounted to much in terms of topping this grim British wonder—his best known movie after this 1972 effort is the fatally banal Dead and Buried (1981)—and he is rumored to be staging a comeback by—what else?—remaking Raw Meat. (Calling George Sluzier! Calling George Sluzier!) He may never make another good movie, but at least he made this one. Commuters in the Russell Square tube station of London have been besieged by a series of kidnap murders,

and brilliantly cranky police inspector Donald Pleasance (in what may be the actor’s best performance) soon discovers the secret behind the crimes-- descendents of survivors of a cave-in when the tube line was being constructed near the turn of the 20th century, Underground workers who were left to die by a contracting company who didn’t want to pay to search for them, have mutated and resorted to cannibalism in an attempt to sustain themselves under the city. Sherman’s pacing is lumpy, and his tonal swings are sometimes a bit too extreme, but the movie has a primal, grotty power—his details of observation regarding this underground world the survivors have fashioned for themselves is nothing less than remarkable-- and it has a surprising emotional heft too. We’re first introduced to the perpetrator of the crimes that will concern the movie, a hulking, malformed, pathetic figure tending to his pregnant wife, at the tail end of a purposeful, long take that guides us through our first glimpse of this catacomb of horrors. The wife dies in childbirth, leaving the man as the only survivor of the ill-fated line that began 60 years previous.

and brilliantly cranky police inspector Donald Pleasance (in what may be the actor’s best performance) soon discovers the secret behind the crimes-- descendents of survivors of a cave-in when the tube line was being constructed near the turn of the 20th century, Underground workers who were left to die by a contracting company who didn’t want to pay to search for them, have mutated and resorted to cannibalism in an attempt to sustain themselves under the city. Sherman’s pacing is lumpy, and his tonal swings are sometimes a bit too extreme, but the movie has a primal, grotty power—his details of observation regarding this underground world the survivors have fashioned for themselves is nothing less than remarkable-- and it has a surprising emotional heft too. We’re first introduced to the perpetrator of the crimes that will concern the movie, a hulking, malformed, pathetic figure tending to his pregnant wife, at the tail end of a purposeful, long take that guides us through our first glimpse of this catacomb of horrors. The wife dies in childbirth, leaving the man as the only survivor of the ill-fated line that began 60 years previous.  But rather than subject the audience to a display of self-righteous fury, Sherman lingers on the man as his expresses his confusion and grief, and then proceeds to inter her body, after finding a piece of jewelry to commemorate her, along with all the rest of the recent dead lying in grisly state in a dank barracks, all of them similarly bejeweled. It’s an overwhelming set piece and informs the rest of the man’s ghastly actions—including a kidnap and near-rape of a woman he hopes will help in his desire to procreate—with a level of empathy that is at once scary and welcome for the added dimensions it brings to what could have been a routine thriller. But Raw Meat is anything but routine—it spikes the audience with humor, horror and heart, its final stop never assured until the last frame. Mind the doors!

But rather than subject the audience to a display of self-righteous fury, Sherman lingers on the man as his expresses his confusion and grief, and then proceeds to inter her body, after finding a piece of jewelry to commemorate her, along with all the rest of the recent dead lying in grisly state in a dank barracks, all of them similarly bejeweled. It’s an overwhelming set piece and informs the rest of the man’s ghastly actions—including a kidnap and near-rape of a woman he hopes will help in his desire to procreate—with a level of empathy that is at once scary and welcome for the added dimensions it brings to what could have been a routine thriller. But Raw Meat is anything but routine—it spikes the audience with humor, horror and heart, its final stop never assured until the last frame. Mind the doors! SEED OF CHUCKY (2004; Don Mancini)

SEED OF CHUCKY (2004; Don Mancini)In 1998, writer Don Mancini (who penned the previous three Child’s Play movies) and veteran Hong Kong director Ronny Yu (The Bride with White Hair) resuscitated the Chucky franchise, which had found itself mired in a creative cul-de-sac common to most franchise sequels, by jettisoning the formula of the first three films, giving Chucky (Brad Dourif) a mate, Tiffany, voice and soul provided by trailer trash vixen Jennifer Tilly, and turning the movie into a combination of a kill movie and a parody of domestic romantic dramas. The movie was stylishly directed and beautifully photographed by Peter Pau (who would win the Oscar for his film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), but despite its outrageous conviction, the formulaic elements involving teens being pursued by Chucky and Tiffany end up dragging the movie down. In 2004, Mancini took the directorial reins himself and concocted a meta-whopper of a concept—the sexually confused offspring of Chucky and Tiffany, named Glen (or Glenda, and voiced by Pippin himself, Billy Boyd) makes his way from a ventriloquist’s convention to Hollywood, where a movie about Chucky and Tiffany is being made, in the hopes of reuniting with his (unknown to him) homicidal parents. But Chucky gets one look at his milquetoast son and doesn’t like what he sees—newly accepting of his superstar status as a killer doll, he’d rather proceed with a plan to artificially inseminate the star of the Chucky movie (Jennifer Tilly again) and come up with a human-doll hybrid to call his and Tiffany’s own. (In one of the movie’s funniest jokes, Chucky collects his load by jerking off to a copy of Fangoria magazine.)

Seed of Chucky gets a leg up on the previous entries by finding a way to break free of the hunter/hunted slasher movie patterns, thus freeing itself to riff even more wildly on the devil dolls’ domestic life-- Ordinary People and the like are the sacred texts defiled here—and, even more successfully, the movie star persona of Jennifer Tilly herself. Every time I see this movie (and I’ve seen it several times now since discovering it on DVD a year after it was in theaters), my awe is renewed at Tilly’s steely, knife-sharp good humor (bolstered by Mancini’s insider perspective—the two are good friends and he knew she’d be game) in dismantling her own sex bomb persona, as well as the pretensions and insecurity attendant to being a Hollywood star, with such abandon. I’ve never seen anyone tread so boldly into this kind of hilarious self-evisceration, and if Tilly never made another good movie she’d still have my undying respect for what she brings to Seed of Chucky. As I said in my original notes in reviewing the movie, this is the kind of performance that ought to be nominated for Oscars, but in a world where women win Oscars for getting ugly via prosthetics or learning lots of ennobling life lessons (usually without a lot of makeup), Tilly is obviously not offering up the right kind of bait. (Check out the copious DVD bonus material and commentaries for more of Tilly’s hilarious personal insights into the creative process.) Mancini deserves a lot of credit too—juggling the elements of a franchise would be difficult enough for a first-time director, but doing it while basically coordinating that franchise’s movement from relatively straight horror film into a much more deft and devious satirical mode, and doing it without sacrificing filmmaking style (and, of course, the gore) is a tall order. But Mancini delivers—he’s obviously a student of De Palma, Argento and Bava, and their visual influences are all over Seed of Chucky, but they don’t impede the flow and sensibility of the movie, they merge with it. The movie has some rough patches and the second half doesn’t move along from scene to scene as smartly as it might, but Mancini has done his baby proud by reinventing Chucky in such a radically funny way. And a strange thing happened upon seeing the clever, Omen-esque ending of Seed-- for the first time in this franchise, and perhaps just about any other horror franchise I can think of, I didn’t wince at the set-up for the next one. Instead, I smiled and spent a few minutes imagining the possibilities. As long as Mancini and Tilly are involved, that’ll be a sequel worth waiting for.

Seed of Chucky gets a leg up on the previous entries by finding a way to break free of the hunter/hunted slasher movie patterns, thus freeing itself to riff even more wildly on the devil dolls’ domestic life-- Ordinary People and the like are the sacred texts defiled here—and, even more successfully, the movie star persona of Jennifer Tilly herself. Every time I see this movie (and I’ve seen it several times now since discovering it on DVD a year after it was in theaters), my awe is renewed at Tilly’s steely, knife-sharp good humor (bolstered by Mancini’s insider perspective—the two are good friends and he knew she’d be game) in dismantling her own sex bomb persona, as well as the pretensions and insecurity attendant to being a Hollywood star, with such abandon. I’ve never seen anyone tread so boldly into this kind of hilarious self-evisceration, and if Tilly never made another good movie she’d still have my undying respect for what she brings to Seed of Chucky. As I said in my original notes in reviewing the movie, this is the kind of performance that ought to be nominated for Oscars, but in a world where women win Oscars for getting ugly via prosthetics or learning lots of ennobling life lessons (usually without a lot of makeup), Tilly is obviously not offering up the right kind of bait. (Check out the copious DVD bonus material and commentaries for more of Tilly’s hilarious personal insights into the creative process.) Mancini deserves a lot of credit too—juggling the elements of a franchise would be difficult enough for a first-time director, but doing it while basically coordinating that franchise’s movement from relatively straight horror film into a much more deft and devious satirical mode, and doing it without sacrificing filmmaking style (and, of course, the gore) is a tall order. But Mancini delivers—he’s obviously a student of De Palma, Argento and Bava, and their visual influences are all over Seed of Chucky, but they don’t impede the flow and sensibility of the movie, they merge with it. The movie has some rough patches and the second half doesn’t move along from scene to scene as smartly as it might, but Mancini has done his baby proud by reinventing Chucky in such a radically funny way. And a strange thing happened upon seeing the clever, Omen-esque ending of Seed-- for the first time in this franchise, and perhaps just about any other horror franchise I can think of, I didn’t wince at the set-up for the next one. Instead, I smiled and spent a few minutes imagining the possibilities. As long as Mancini and Tilly are involved, that’ll be a sequel worth waiting for. THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE PART TWO (1986; Tobe Hooper)

THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE PART TWO (1986; Tobe Hooper)Tobe Hooper’s sequel to his seminal 1974 nightmare is easily the most critically vilified (and therefore most heinously underrated) movie on this list, and it’s easy to see why. Those who thought well-enough should be left alone probably didn’t think a sequel was a good idea no matter what form it took, and perhaps there was some resentment for perceived opportunism on Hooper’s part for revisiting TCM in the shadow of a post-Poltergeist career that wasn’t shaping up (the flops Lifeforce and Invaders for Mars) the way he might have hoped. On the other hand, horror geeks clamoring for more of Leatherface and family would probably have been more satisfied with the subsequent more literal-minded (and increasingly nihilistic) sequels and remakes that have emerged since The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2 bowed in the summer of 1986.

No one, I suspect, figured that Hooper would take his most respected movie, which did have elements of humor amidst the charnel house horrors, and turn it into a grotty, satirical comedy. But that’s just what TCM2 is— part self-aware sequel that ups the graphic gore quotient (the movie was released unrated), but much more a hilarious swipe at the perils of running a small business— the family has moved on from slaughterhouses to a lucrative operation catering chili made out of you-know-what. “That’s prime meat!” says oldest brother Drayton Sawyer (Jim Siedow) when asked the secret of his delicious recipe as he takes yet another first prize at a local chili cook-off. Moments later, a news reporter bites down on something hard and spits out something that looks an awful lot like a molar. “That’s one of them… hard peppercorns,” scoffs Drayton, and the crowd cheers. But business gets tougher when Leatherface and way-

No one, I suspect, figured that Hooper would take his most respected movie, which did have elements of humor amidst the charnel house horrors, and turn it into a grotty, satirical comedy. But that’s just what TCM2 is— part self-aware sequel that ups the graphic gore quotient (the movie was released unrated), but much more a hilarious swipe at the perils of running a small business— the family has moved on from slaughterhouses to a lucrative operation catering chili made out of you-know-what. “That’s prime meat!” says oldest brother Drayton Sawyer (Jim Siedow) when asked the secret of his delicious recipe as he takes yet another first prize at a local chili cook-off. Moments later, a news reporter bites down on something hard and spits out something that looks an awful lot like a molar. “That’s one of them… hard peppercorns,” scoffs Drayton, and the crowd cheers. But business gets tougher when Leatherface and way- disturbed brother Chop Top (Bill Moseley, Otis Driftwood of The Devil’s Rejects, in a near-brilliant performance filled with twisted slapstick and vocal acrobatics) attract the attention of a radio deejay named Stretch (Caroline Williams) when the sounds of them sawing up a couple of drunken frat boys on their way to the Oklahoma-Texas “Red River Shootout” football weekend accidentally gets broadcast live on the air.

disturbed brother Chop Top (Bill Moseley, Otis Driftwood of The Devil’s Rejects, in a near-brilliant performance filled with twisted slapstick and vocal acrobatics) attract the attention of a radio deejay named Stretch (Caroline Williams) when the sounds of them sawing up a couple of drunken frat boys on their way to the Oklahoma-Texas “Red River Shootout” football weekend accidentally gets broadcast live on the air.  (The frat boys have been harassing Stretch and end up leaving their car phone off the hook for the last moments of their lives.) This, in turn, attracts the attention of crazed Texas Ranger Lefty Enright (Dennis Hopper, typically mid-80s Hopper-esque), a relative of one of the victims from the 1974 film who has been tracking the Sawyers with an almost religious fervor, and he uses Stretch as bait to lure the Sawyers out in the open. The final encounter between Lefty, Stretch (who has been kidnapped by a smitten Leatherface) and the Sawyer boys, in the catacombs underneath an old carnival which serves as their cannibal catering headquarters, is surrealistic, suspenseful and hilarious, though none too subtle— when Drayton gets cut in the hindquarters by Lefty’s enormously phallic blade,

(The frat boys have been harassing Stretch and end up leaving their car phone off the hook for the last moments of their lives.) This, in turn, attracts the attention of crazed Texas Ranger Lefty Enright (Dennis Hopper, typically mid-80s Hopper-esque), a relative of one of the victims from the 1974 film who has been tracking the Sawyers with an almost religious fervor, and he uses Stretch as bait to lure the Sawyers out in the open. The final encounter between Lefty, Stretch (who has been kidnapped by a smitten Leatherface) and the Sawyer boys, in the catacombs underneath an old carnival which serves as their cannibal catering headquarters, is surrealistic, suspenseful and hilarious, though none too subtle— when Drayton gets cut in the hindquarters by Lefty’s enormously phallic blade,  he hides under a table and bemoans, “The small businessman’s always taking it in the ass,” thinking more about the revenue this battle is costing him by not being able to show up for all those football weekend tailgate parties than the fact that he has, in fact, just taken it in the ass. If you don’t believe me aboutTCM2, just ask Edward Copeland, who raved about it earlier this year. Edward actually likes it better than the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. While I can’t go that far, I maintain that is a very good, grotesquely funny movie, one that still hasn’t shrugged off the stink of its bad reputation even 20 years after its release, and it’s alone worth seeing for what Moseley does with a cigarette lighter and a wire hanger to relieve the incessant itch around the edges of the metal plate in his head.

he hides under a table and bemoans, “The small businessman’s always taking it in the ass,” thinking more about the revenue this battle is costing him by not being able to show up for all those football weekend tailgate parties than the fact that he has, in fact, just taken it in the ass. If you don’t believe me aboutTCM2, just ask Edward Copeland, who raved about it earlier this year. Edward actually likes it better than the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. While I can’t go that far, I maintain that is a very good, grotesquely funny movie, one that still hasn’t shrugged off the stink of its bad reputation even 20 years after its release, and it’s alone worth seeing for what Moseley does with a cigarette lighter and a wire hanger to relieve the incessant itch around the edges of the metal plate in his head. ***********************************************************************

HONORABLE HORRIBLE MENTION goes to a second set of 13 titles, some of which are obscure, some far too well-known and venerated to ever be considered underrated, ignored or forgotten, but none of which are frequently mentioned when those “Best/Favorite” lists get compiled. The list below features a greater range of quality than the list above, but even the least of them (probably Society or Cemetery Man) are still worth a look, and many (The Fearless Vampire Killers…, Near Dark, Ugetsu, Carnival of Souls) should be in every horror fan’s DVD library, or at least on their Netflix queue.

ALLIGATOR (1980; Lewis Teague)

Script by John Sayles. A great, scary parody of Jaws with terrific character turns from Robert Forster and Henry Silva, channeling Scheider and Shaw, respectively.

ALUCARDA (1975; Juan Lopez Moctezuma)

Strange, lurid, compulsively watchable Mexican horror film. For more information, check out K. Lindbergs’ thorough assessment at Cinebeats: Confessions of a Cinephile

CARNIVAL OF SOULS (1962; Herk Harvey)

Eerie and unsettling, a crisis of alienation masking as a low-budget ghost story.

CEMETERY MAN (1995; Michele Soavi)

Argento associate Soavi comes up with his own take on zombie love. Mostly arch and annoying, but with a beautiful, poetic ending-- it may be better than I originally gave it credit for being. It’s on deck from Netflix for a second look.

THE FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS… or PARDON ME, BUT YOUR TEETH ARE IN MY NECK (1967; Roman Polanski)

Polanski’s parody of Hammer horror is scary, disturbing and funny, often all at the same time, and over-the-top almost all the time.

GOD TOLD ME TO (aka Demon) (1977; Larry Cohen)

Borderline incoherent in spots, but a very effective grindhouse thriller about the apparent religious mania surrounding a series of unrelated killings in New York City. Bizarre and fascinating.

NEAR DARK (1987; Kathryn Bigelow)

Edgy, brilliant cowboy-vampire hybrid is steeped in intoxicatingly dark imagery, and features a standout performance by Joshua Miller as a 150-year-old vampire trapped in the body of a 12-year-old boy, the age he was when he was bitten.

RACE WITH THE DEVIL (1975; Jack Starrett)

This horror movie-chase thriller is a scuzzy, low-grade ’70s hoot from its revved-up start all the way to its sudden ending, as viewed from the center of a flaming circle sent from hell.

THE RELIC (1997; Peter Hyams)

A monster-in-a-museum shocker that is far better and scarier than it had any right to be. (Did you notice who directed?)

SOCIETY (1992; Brian Yuzna)

Interesting, half-creepy, half annoying late ‘80s artifact has upper-crust society literally absorbing the lower classes. Honorable attempt at social satire has lots of bad hair and good, surrealistic effects.

TRAUMA (1993; Dario Argento)

Lots of decapitations, and Piper Laurie, in this largely overlooked Argento funhouse attraction.

UGETSU MONOGATARI (1953; Kenji Mizoguchi)

This gorgeous, unsettling Japanese ghost story will get under your skin, no matter what you do to protect yourself.

VAMPYR (1932; Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Fascinating, moody vampire story is told through a cornucopia of film techniques and devices. Less interesting as a narrative than as a textbook on the possibilities of mood and fear achieved almost entirely through directorial style.

************************************************************************************

Writer-Director Don Mancini’s 10 UNDER-APPRECIATED HORROR FILMS

Earlier this year, some four months after I had posted and forgotten a mostly positive initial review of Seed of Chucky, I received an e-mail from its director, Don Mancini, writer of all five Chucky films, thanking me for all the kind words I’d written about his movie, and even for a couple of backhanded criticisms, and for consistently writing about the horror genre from a sincerely interested, non-condescending point of view. He said too that he had forwarded my review along to Jennifer Tilly herself, who was thrilled and excited about it. All of this did nothing but make me giddy, alongside being amazed that someone whose film I wrote about actually read my thoughts and took the time to contact me. We ended up going out for coffee a couple of weeks later, and I discovered that Don, who is only a couple of years younger than I am, is about as friendly and unpretentious a person as I have ever met. We grew up on many of the same good—and bad—movies (Don is the only other person I’ve ever met beside my best friend who knows exactly how great The Boys from Brazil truly is), and he turns out to be a voracious consumer of film criticism as well.

Earlier this year, some four months after I had posted and forgotten a mostly positive initial review of Seed of Chucky, I received an e-mail from its director, Don Mancini, writer of all five Chucky films, thanking me for all the kind words I’d written about his movie, and even for a couple of backhanded criticisms, and for consistently writing about the horror genre from a sincerely interested, non-condescending point of view. He said too that he had forwarded my review along to Jennifer Tilly herself, who was thrilled and excited about it. All of this did nothing but make me giddy, alongside being amazed that someone whose film I wrote about actually read my thoughts and took the time to contact me. We ended up going out for coffee a couple of weeks later, and I discovered that Don, who is only a couple of years younger than I am, is about as friendly and unpretentious a person as I have ever met. We grew up on many of the same good—and bad—movies (Don is the only other person I’ve ever met beside my best friend who knows exactly how great The Boys from Brazil truly is), and he turns out to be a voracious consumer of film criticism as well. We spent nearly three hours that afternoon discovering how much we had in common, talking about family, writing and, of course, movies, movies, and then often, for a break, we’d talk about movies. Since then we’ve become friends, exchanging e-mails and catching films together regularly. When I told Don I was compiling a list of underrated, ignored or forgotten horror movies and that I planned to include Seed of Chucky on it, he said he was honored but wanted to be sure I knew that he could take it if I really didn’t like some of his work. I told him I believed him, then quickly reminded him that I didn’t like Child’s Play 2 or 3 and had mixed feelings about Bride of Chucky, and that he could be assured I wouldn’t wax enthusiastic about anything I didn’t truly enjoy. I even asked him for suggestions of films to watch while compiling my list, and he quickly sent over ten very good suggestions, most of which I liked too. (With one glaring exception, which proves that I don’t like every movie that deals with cannibalism.)

But when I finalized my own list, I realized that we only really overlapped on one film-- Parents. So I took that one off my list, e-mailed Don, and asked him if he would mind if I printed his entire list as an addendum to my own, bringing the number of movies talked about in this post to a ridiculous 36, and he was very much in favor of the idea. So it is now my honor to introduce Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule’s very first guest contributor, my friend Don Mancini, writer-director of Seed of Chucky, and his own personal list of 10 Underrated Horror Movies, listed in order of their release.

THE FURY (1978; Brian De Palma)

Brian De Palma’s adaptation of John Farris’s novel wasn’t nearly as popular as the director’s classic Carrie, probably due to The Fury’s complicated, bipartite story. But it’s a masterfully directed film in its own right. With breathtaking panache, De Palma deploys his battery of trademark visual tricks—jump cuts, split-field lenses, slow motion, stealthily circling cameras—to evoke the surreal mindscapes of the telepaths Amy Irving and Andrew Stevens, “psychic twins” exploited for their espionage potential by nefarious G-man John Cassavetes. The protagonists’ uncontrollable ability to make people bleed simply by touching them gives rise to a series of brilliantly shocking scenes of stylized violence ,

culminating in Cassavetes’ literally explosive demise. Amy Irving’s trembling, emotional performance as the troubled psychic girl underlines the film’s subtext—one of De Palma’s pet themes—of an innocent, vulnerable young person’s inevitable corruption by the hostile “real world.” Other highlights include a telepathic vision on a staircase, sporting ravishing, dream-like imagery that is the quintessence of gothic horror; a wordless, slow-motion chase sequence which is a textbook example of expert visual storytelling; and one of John Williams’s best-ever scores. The late, great critic Pauline Kael wrote of The Fury, “No Hitchcock thriller was ever so intense, went so far, or had so many classic sequences.”

culminating in Cassavetes’ literally explosive demise. Amy Irving’s trembling, emotional performance as the troubled psychic girl underlines the film’s subtext—one of De Palma’s pet themes—of an innocent, vulnerable young person’s inevitable corruption by the hostile “real world.” Other highlights include a telepathic vision on a staircase, sporting ravishing, dream-like imagery that is the quintessence of gothic horror; a wordless, slow-motion chase sequence which is a textbook example of expert visual storytelling; and one of John Williams’s best-ever scores. The late, great critic Pauline Kael wrote of The Fury, “No Hitchcock thriller was ever so intense, went so far, or had so many classic sequences.”DRACULA (1979; John Badham)

Francis Coppola’s 1992 version gets all the accolades, as well as the credit for popularizing the eponymous vampire as a predominantly romantic figure, but John Badham’s film starring Frank Langella did it first. It’s a sumptuous, grandly mounted entertainment, with gorgeous cinematography, beautiful Albert Whitlock matte paintings, a terrific score (John Williams again), and clever in-camera trick effects which remain surprisingly effective in our CG-reliant era.

Laurence Olivier, affecting a mellifluous Dutch accent, makes a charming and unusually emotional Van Helsing who, in this version, is given a more personal stake (forgive the pun) in the proceedings, due to screenwriter W.D. Richter recasting him as he mournful—and vengeful—father of Dracula’s first victim. Olivier’s anguished cry as he is forced to destroy his now-demonic daughter is unforgettably heartbreaking. A completely engrossing version of a venerable classic, with unique details (such as the Maurice Binder-designed love scene) that nostalgically mark it as part of its particular era.

THE HUNGER (1983; Tony Scott)

Usually dismissed as an empty exercise in style, Tony Scott’s adaptation of Whitley Streiber’s modern vampire tale is actually about emptiness and style. The film evokes a narcissistic culture which values youth and beauty—and style—above love and truth, and it offers a truly horrifying metaphor for our society’s penchant for disposable relationships: when lovers of ultra-chic, New Wave vampire Catherine Deneuve grow so hideously old that she can no longer even bear to kiss them, she simply sticks them in a box, stows them in the attic, and moves on to her next conquest—in this case, Susan Sarandon, in a plot development which gives rise to the notoriously titillating lesbian sex scene.

Seen in its proper historical context—the dawning of the AIDS era-- The Hunger becomes a stinging rebuke to a waning age of hedonism and promiscuity, and a sobering reminder that many of the most effective horror films are, at heart, deeply conservative. Few movies so powerfully address the genre’s fundamental concern—the universal fear of aging and death. The sequence in which David Bowie ages from virile young man to doddering geriatric in the span of a few minutes, aided by Dick Smith’s excellent make-up, is a classic. Scott’s fashion-magazine visuals were, along with Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo, harbingers of a decade-defining aesthetic of soft-focus pastels that was eventually popularized by Miami Vice.

Seen in its proper historical context—the dawning of the AIDS era-- The Hunger becomes a stinging rebuke to a waning age of hedonism and promiscuity, and a sobering reminder that many of the most effective horror films are, at heart, deeply conservative. Few movies so powerfully address the genre’s fundamental concern—the universal fear of aging and death. The sequence in which David Bowie ages from virile young man to doddering geriatric in the span of a few minutes, aided by Dick Smith’s excellent make-up, is a classic. Scott’s fashion-magazine visuals were, along with Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo, harbingers of a decade-defining aesthetic of soft-focus pastels that was eventually popularized by Miami Vice.LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS (1986; Frank Oz)

Like its bloodthirsty featured creature, a carnivorous potted plant named Audrey II, Frank Oz’s version of an Off-Broadway stage production, itself a remake of a cheap Roger Corman flick from 1960, is a crowd-pleasing mutation, a spoofy hybrid of musicals and 1950s monster movies. It is, in every way, at least the equal of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, but it never attained anywhere near that film’s cult status—a matter of timing, perhaps, illustrating a telling difference between the film’s respective eras (Rocky’s experimental ‘70s vs. Little Shop’s homogenized ‘80s). Oz, a great director of comedy, also displays tremendous flair for the kind of stylized theatricality on which horror—and, for that matter, musicals—often thrive; lighting, production design and camera angles create a unique, hermetically sealed world, absolutely crucial for this sort of arch material. The cast of legends includes Rick Moranis; Steve Martin and Bill Murray, hilarious together as, respectively, a sadistic dentist and his masochistic patient; and, in memorable cameos, John Candy and Christopher Guest. The terrific songs are by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman. Little Shop of Horrors makes you laugh, affectionately and uproariously, at the conventions and gimmicks of the genre.

Like its bloodthirsty featured creature, a carnivorous potted plant named Audrey II, Frank Oz’s version of an Off-Broadway stage production, itself a remake of a cheap Roger Corman flick from 1960, is a crowd-pleasing mutation, a spoofy hybrid of musicals and 1950s monster movies. It is, in every way, at least the equal of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, but it never attained anywhere near that film’s cult status—a matter of timing, perhaps, illustrating a telling difference between the film’s respective eras (Rocky’s experimental ‘70s vs. Little Shop’s homogenized ‘80s). Oz, a great director of comedy, also displays tremendous flair for the kind of stylized theatricality on which horror—and, for that matter, musicals—often thrive; lighting, production design and camera angles create a unique, hermetically sealed world, absolutely crucial for this sort of arch material. The cast of legends includes Rick Moranis; Steve Martin and Bill Murray, hilarious together as, respectively, a sadistic dentist and his masochistic patient; and, in memorable cameos, John Candy and Christopher Guest. The terrific songs are by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman. Little Shop of Horrors makes you laugh, affectionately and uproariously, at the conventions and gimmicks of the genre.THE BELIEVERS (1986; John Schlesinger)

There isn’t much going on beneath the surface of this contemporary witchcraft story—although its urban voodoo cult seems a deliberate updating of the coven in Rosemary’s Baby, The believers has no real subtextual or metaphoric resonance. Still, it’s a slick occult thriller, well directed by John Schlesinger. Martin Sheen plays a widower who becomes embroiled with a sinister sect devoted to bugeria, a form of black magic whose practitioners perform ritual child sacrifice. Sheen doesn’t know whom to trust when the cult zeroes in on his own little boy (Harley Cross, who also played the title role in The Fly II.). Schlesinger stages some truly hair-raising moments: an extremely disturbing and seemingly realistic death-by-electrocution; an autopsy which looses live, wriggling snakes from a victim’s guts; and, most memorably, a voodoo-induced zit which pops and spouts a nest of skittering spiders across leading lady Helen Shaver’s horrified face. The film also features a creepy, glassy-eyed witch-doctor assassin (Khali Keyi). Finally, The Believers is noteworthy because nowadays its children-in-peril premise would never see the light of day.

There isn’t much going on beneath the surface of this contemporary witchcraft story—although its urban voodoo cult seems a deliberate updating of the coven in Rosemary’s Baby, The believers has no real subtextual or metaphoric resonance. Still, it’s a slick occult thriller, well directed by John Schlesinger. Martin Sheen plays a widower who becomes embroiled with a sinister sect devoted to bugeria, a form of black magic whose practitioners perform ritual child sacrifice. Sheen doesn’t know whom to trust when the cult zeroes in on his own little boy (Harley Cross, who also played the title role in The Fly II.). Schlesinger stages some truly hair-raising moments: an extremely disturbing and seemingly realistic death-by-electrocution; an autopsy which looses live, wriggling snakes from a victim’s guts; and, most memorably, a voodoo-induced zit which pops and spouts a nest of skittering spiders across leading lady Helen Shaver’s horrified face. The film also features a creepy, glassy-eyed witch-doctor assassin (Khali Keyi). Finally, The Believers is noteworthy because nowadays its children-in-peril premise would never see the light of day.LADY IN WHITE (1988; Frank LaLoggia)

Frank LaLoggia’s low-budget ghost story is pleasingly old-fashioned, with an emphasis on narrative over spectacle. On Halloween night in 1962, a 10-year-old boy (Lukas Haas) is locked in a school closet by bullies. Trapped, he is terrified to witness the relentless spirit of a murdered little girl reenacting her grisly demise at the hands of an unseen killer.

The boy is determined to bring the killer to light and set the girl’s spirit free. The plot sounds familiar, but what hooks you are the details: the kid’s close-knit Italian-Catholic family; the spritely tune, whistled by the killer, which becomes a dread harbinger of lurking danger; and the archetypal small-town atmosphere, with its simmering racial tensions straight out of To Kill a Mockingbird. LaLoggia also has a gift for staging gasp-inducing shocks (as he first demonstrated in his 1981 Antichrist flick Fear No Evil). Despite its shortcomings—the killer’s identity is signaled too early, some of the effects are distractingly cheesy, and the treacle gets a bit thick at the end-- Lady in White is a sure-handed charmer.

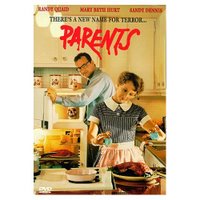

The boy is determined to bring the killer to light and set the girl’s spirit free. The plot sounds familiar, but what hooks you are the details: the kid’s close-knit Italian-Catholic family; the spritely tune, whistled by the killer, which becomes a dread harbinger of lurking danger; and the archetypal small-town atmosphere, with its simmering racial tensions straight out of To Kill a Mockingbird. LaLoggia also has a gift for staging gasp-inducing shocks (as he first demonstrated in his 1981 Antichrist flick Fear No Evil). Despite its shortcomings—the killer’s identity is signaled too early, some of the effects are distractingly cheesy, and the treacle gets a bit thick at the end-- Lady in White is a sure-handed charmer. PARENTS (1988; Bob Balaban)

Bob Balaban, an actor known to genre fans for movies like Close Encounters and Altered States, made his feature directing debut with this idiosyncratic and very effective indie horror comedy.

A 1950s-era suburban boy (Bryan Mardorsky) wakes up in the middle of the night, toddles downstairs for a glass of water, and spies his picture-perfect parents (Randy Quaid and Mary Beth Hurt) indulging in some shocking behavior. Confused by what he sees, he concludes that Mom and Dad are cannibals. Is he right, or is his innocent young mind misinterpreting the primal scene? The Freudian implications are deftly handled by Balaban, who shows impressive control with his rigorously designed, expressionistic visuals: low angles and deep focus make the parents loom threateningly in their tract house lair. Quaid and Hurt are terrifying, their rictus smiles frozen in place, and Sandy Dennis is a hoot as the kid’s flaky psychologist and trusted confidante. Madorsky pays her the ultimate compliment when, admiring her cluttered office and messy appearance, he tells her, “You’re not a real grown-up.”

A 1950s-era suburban boy (Bryan Mardorsky) wakes up in the middle of the night, toddles downstairs for a glass of water, and spies his picture-perfect parents (Randy Quaid and Mary Beth Hurt) indulging in some shocking behavior. Confused by what he sees, he concludes that Mom and Dad are cannibals. Is he right, or is his innocent young mind misinterpreting the primal scene? The Freudian implications are deftly handled by Balaban, who shows impressive control with his rigorously designed, expressionistic visuals: low angles and deep focus make the parents loom threateningly in their tract house lair. Quaid and Hurt are terrifying, their rictus smiles frozen in place, and Sandy Dennis is a hoot as the kid’s flaky psychologist and trusted confidante. Madorsky pays her the ultimate compliment when, admiring her cluttered office and messy appearance, he tells her, “You’re not a real grown-up.”DEATH BECOMES HER (1992; Robert Zemeckis)

This horror comedy, directed by Robert Zemeckis, was aptly described by co-writer David Koepp as “Noel Coward meets Night of the Living Dead. Like The Hunger, its subject is narcissism, but here the tone is darkly comic, as catty lifelong enemies Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn vie for the secret of eternal youth in

image-obsessed Beverly Hills. After ingesting a potion which prevents them from aging, dying, or even feeling pain, the hateful leading ladies keep trying to kill each other, over and over again, while the Oscar-winning CG effects allow for their bodies to be violently twisted, punctured, and ultimately shattered—all played off the characters’ hilariously nonchalant reactions. The eye-popping visuals are accompanied by side-splitting dialogue (such as Streep’s priceless ”Now a warning?” to sorceress Isabella Rossellini after drinking the latter’s proffered potion.) The first cut of the film contained a subplot featuring Tracey Ullman, whose character figured in the original script’s surprisingly poignant—and presumably too incongruous—ending; here’s hoping that this excised material will be made available on some future DVD.

image-obsessed Beverly Hills. After ingesting a potion which prevents them from aging, dying, or even feeling pain, the hateful leading ladies keep trying to kill each other, over and over again, while the Oscar-winning CG effects allow for their bodies to be violently twisted, punctured, and ultimately shattered—all played off the characters’ hilariously nonchalant reactions. The eye-popping visuals are accompanied by side-splitting dialogue (such as Streep’s priceless ”Now a warning?” to sorceress Isabella Rossellini after drinking the latter’s proffered potion.) The first cut of the film contained a subplot featuring Tracey Ullman, whose character figured in the original script’s surprisingly poignant—and presumably too incongruous—ending; here’s hoping that this excised material will be made available on some future DVD.HANNIBAL (2001; Ridley Scott)