I don’t get out as much as I used to, and notice of that fact is certainly meant to include the frequency with which I make it out to the theater to see a movie. I think it’s because we find ourselves in what I’ll call, for lack of a better term, the Netflix Age of streaming and immediate access of some very high-profile releases, as well as a lot of “buried “treasures that aren’t quite as magazine- and newspaper-profile friendly, that my list this year is weighted so heavily toward movies I saw at home.

There are 11 movies that I placed at the very top of my list of favorites. Of those 11 I saw exactly one of them in a theater, and it wasn’t the one I now, with retroactive desperation, wish I’d seen in a theater. (Just before putting this piece to bed, I did see Pixar’s exceedingly gorgeous and emotionally overwhelming Coco on the big screen, and I’m really glad I did—if I’d made room for 12 movies on my list instead of just the arbitrary 11, it might well have been on it.) My Movie Pass card just came in the mail today, so maybe that watershed event will signal a restoration of the balance back toward attending more traditional exhibitions in 2018.

Of the many movies I included on my honorable mentions list, there are 22 that I saw theatrically; those are mostly the sort of top-notch blockbuster fare that turned out to be a whole lot better than maybe even my highest expectations, yet not quite good enough to think about in terms of the year’s peachiest highlights.

Finally, as if to insist that the theatrical experience is no guarantor of quality (either in presentation or the movie’s achievement), my candidate for worst movie of the year is one I took in with my family on a Saturday night in multiplexland, and the movie itself is the furthest thing from the sort of superhero-sci-fi-blockbuster mind-melt so often fretted over by those culture mavens who insist they know better.

While we’re at it, please note the phrase “my favorite.”

If only to clarify the obvious, I have in no way traveled the completist road

of the professional critic, this year or most any other. I haven’t come close

to seeing the number of movies it would require for me to declare with any sort

of confidence (most likely false, whatever sort) that the movies on my list

were “the best.” Frankly, I don’t even see how professional critics could use

the term “best,” or why they’d even want to. Year-end lists are confetti

parties of subjective summation, the culling together of one’s experience and,

hopefully, a soupcon of observation that serves as an autobiography of taste as

much as it does any sort of cumulative movie culture reckoning. Lists of

year-end movie favorites are arbitrary, subjective, often illogical, maddening

and maybe even surprising; I certainly think mine is probably one or all of those

things, and if it’s surprising, then maybe that means I’m at least pointing the

way toward a movie the reader may not have considered before.

I published this list on Facebook earlier this year and it was pointed out to me with frequency and relish just how much good stuff I have yet to see. So then, in order to forefront my deficiencies, let me note that I have yet to experience such year-end forces of nature as The Florida Project (next week, maybe), Phantom Thread, Faces Places, BPM, In the Fade, Columbus, The Disaster Artist, Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, Marjorie Prime, Last flag Flying, Molly’s Game, I, Tonya and All the Money in the World. And may I further note the realization that with the inclusion of one title in particular in my top 11 I have likely lost a shit-ton of credibility within my own house, to say nothing of the respect for the many folks (some of whom are professional film critics) whose opinions and process of thought I trust and admire, here are the movies of 2017 I liked best, from tippity-top-toppest to least-of-the-tippity-top:

Wormwood (Errol Morris)

In every way possible, the heightening and summation of everything Errol Morris has achieved as an investigative documentarian, this is a complex, unsettling, frightening, totally mesmerizing experience—the layers of truth and deception that are revealed as a son tries to make sense of the death of his father, who plunged to his death from a New York city hotel room after being unwittingly administered LSD as part of a behavioral experiment, is devastating in its portrayal of how obsession can never be fully satisfied, and how it subsumes and displaces the life of the obsessed. No movie I saw this year, of any length (it runs 241 minutes, plus intermission, in its theatrical incarnation) held me as rapt; no other cinematic journey was this absorbing; no other single work in 2018 did so much to redefine the parameters and possibilities within its chosen genre as did Wormwood. (Netflix)

Slack Bay (Bruno Dumont)

One of the few movies I saw this year for which I was

able to go in totally blind, absolutely unsure of what I was getting myself

into, and a better state for receiving Dumont’s absurdly beautiful, sometimes

mean-spirited and often transcendent farce there is not. The sense of not

knowing where a movie is going, and being completely thrilled at the prospect

of finding out, is a rarity; by the end I felt like I was floating. (Netflix)

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (Martin McDonagh)

Besides offering a showcase for Frances McDormand’s dominating, yet at times surprisingly subtle performance, McDonagh’s most significant achievement with his latest, a superb comedy of agony and varying shades of anger which is very much the work of the man who made In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths, is its absolute conviction that no fury is ever thoroughly righteous, and that those we’ve decided are monsters may have surprising, if not redeeming, dimension. (General release)

Besides offering a showcase for Frances McDormand’s dominating, yet at times surprisingly subtle performance, McDonagh’s most significant achievement with his latest, a superb comedy of agony and varying shades of anger which is very much the work of the man who made In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths, is its absolute conviction that no fury is ever thoroughly righteous, and that those we’ve decided are monsters may have surprising, if not redeeming, dimension. (General release)

Personal Shopper (Olivier Assayas)

A ghost story for audiences who enjoy the tease of the

tale, the interruptions of mundane, pseudo-glamorous reality into realms of

spectral speculation and, conversely, the subtle assertion of the spiritual

into the material. The movie eschews big set pieces for subdued subversion and as

a result it is deliberately and unfailingly unsettling all the way. Assayas’

new muse, Kristen Stewart, is terrific while displaying almost no distracting

fireworks of “technique.” (Streaming and Criterion Blu-ray)

Spettacolo (Jeff Malmberg, Chris

Shellen)

A Tuscan village defines and discusses its history and

its present concerns through an annual theatrical production, and the movie

made of the endeavor raises sobering questions of tradition, representation,

and the value of art for audiences and performers far removed from any elite.

It’s hard to remember seeing a movie that made the act of creation seem like

such a vital, desperate, necessary thing. (Streaming)

Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond—Featuring

a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Mention of Tony Clifton (Chris Smith)

The last movie I saw in 2017, one preceded immediately by Spettacolo, and the two seem to me entwined through their engagement with the idea of the ineffable,sometimes uncontrollable impulses that inspire artists to do what they do. Carrey's method-deranged submersion into the character of Andy Kaufman (and Tony Clifton), as documented in never-before-seen footage shot on the set of the Kaufman biopic Man in the Moon is at turns fascinating, frightening, befuddling and possibly dangerous, and the actor commenting on his own apparent flirtation with madness carries with it its own deep wells of melancholy. If only Man in the Moon had been this adept at exploring the harsh, unknowable genius of its protagonist. (Netflix)

The last movie I saw in 2017, one preceded immediately by Spettacolo, and the two seem to me entwined through their engagement with the idea of the ineffable,sometimes uncontrollable impulses that inspire artists to do what they do. Carrey's method-deranged submersion into the character of Andy Kaufman (and Tony Clifton), as documented in never-before-seen footage shot on the set of the Kaufman biopic Man in the Moon is at turns fascinating, frightening, befuddling and possibly dangerous, and the actor commenting on his own apparent flirtation with madness carries with it its own deep wells of melancholy. If only Man in the Moon had been this adept at exploring the harsh, unknowable genius of its protagonist. (Netflix)

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) (Noah Baumbach)

Anchored by career-best performances from Ben Stiller and

Adam Sandler, and a real eye-opener from Elizabeth Marvel (she was the

40-year-old Mattie in the Coen Brother’s True

Grit), Baumbach’s slice-of-New York family comedy works much of the same

territory as his The Squid and the Whale,

but it’s not frozen by its cynicism and it ends up cutting far deeper. And it’s

a hell of a lot more fun to watch; the family dynamics revolving around entitled

Meyerowitz paterfamilias Dustin Hoffman, a sculptor harboring resentment at

being largely set aside by the art world, are superbly realized, and Baumbach

and his editor, Jennifer Lame, deserve some sort of award for their deftness in

cutting away from characters (particularly Sandler’s) in mid-rage. The funniest

movie of the year. (Netflix)

Dawson City: Frozen Time (Bill Morrison)

The history of a small town in the Yukon, and the early

history of the movies themselves, as told through 35mm footage of silent films

thought forever lost, then found buried in permafrost. Viewing Morrison’s

assemblage of ghosts, their stories told largely without spoken words, takes on

the quality of peering through glass into another vaguely recognizable

dimension, one made even more delicate, like the remnants of a disturbing

dream, by being embellished with and sealed in varying degrees of disintegrating

celluloid. (Streaming)

Kedi (Ceyda Torun)

One could spend a lot of time, if one was inclined,

arguing about whether this jaw-dropping documentary is more about the cats who

rule the streets of Istanbul or, like Morris’ great Gates of Heaven, more about the people who care for them, who are

cared for by them. That both answers

are correct indicates the degree of emotional and empathetic depth Torun has

managed to tap. Kedi might be one of

those movies you judge relationships by—if he/she doesn’t like it, well… One

thing’s for sure-- That Darn Cat this

ain’t. (Streaming)

Detroit (Kathryn Bigelow)

Bigelow’s harrowing docudrama takes the infamous Algiers Motel incident as a microcosm of horror from which to expand on the agony and righteous frustration that fueled the Detroit riots of 1967. The immediate experience of Detroit is almost suffocating in its brutality, which is perhaps why it wasn’t a big Saturday night date draw when it briefly surfaced at the beginning of August before disappearing from theaters. But you should steel up and take a look on Blu-ray—it’s a surprisingly expansive work, emotionally speaking, full of unexpected grace notes amidst the unfolding nightmare. Were it less one-note in the depiction of the Detroit officers who perpetuated the torture, it might well have been a sickening masterpiece. (Streaming)

Bigelow’s harrowing docudrama takes the infamous Algiers Motel incident as a microcosm of horror from which to expand on the agony and righteous frustration that fueled the Detroit riots of 1967. The immediate experience of Detroit is almost suffocating in its brutality, which is perhaps why it wasn’t a big Saturday night date draw when it briefly surfaced at the beginning of August before disappearing from theaters. But you should steel up and take a look on Blu-ray—it’s a surprisingly expansive work, emotionally speaking, full of unexpected grace notes amidst the unfolding nightmare. Were it less one-note in the depiction of the Detroit officers who perpetuated the torture, it might well have been a sickening masterpiece. (Streaming)

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (Luc Besson)

Every ostensibly eye-popping CGI blockbuster promises to

show you things you’ve never seen in ways you’ve never seen them. Valerian is one of the only ones,

certainly this year, to actually come through on that pledge. All the rest

probably have better acting (I spent at least a few minutes thinking about my

own recasting of the leads), and maybe even more coherent storytelling.

(Maybe). But none sported more “Oh, my God!” moments of visual beauty, hell, poetry, than Besson’s loony masterwork,

more breathtaking, delirium-inducing, disorientingly exhilarating action

sequences. And no other movie featured a cabaret number by a shape-shifting

Rihanna. I know why you skipped it in theaters—for the same reason I did. But

why are you waiting now? (Streaming, Blu-ray)

Other movies of 2017 I thought were, to one degree or another, perfectly keen (in alphabetical order):

Alien: Covenant, All I

See is You, Beach Rats, Beatriz at Dinner, The Beguiled, Blade of the Immortal,

Blade Runner 2049, The Breadwinner, Bugs, Buster’s Mal Heart, Call Me By Your

Name, Coco, Dunkirk, Gerald’s Game, Get Out, Ghost in the Shell, A Ghost Story,

Graduation, I Called Him Morgan, Icarus, Ingrid Goes West, It, It Comes at

Night, John Wick: Chapter 2, Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle, Justice League,

Kong: Skull Island, Lady Bird, Life, Logan, Logan Lucky, The Lost City of Z,

Mudbound, My Cousin Rachel, Nocturama, Okja, The Post, Shadowman, The Shape of

Water, Spider-Man: Homecoming, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, T2: Trainspotting, Their

Finest, Thor: Ragnarock, Trophy, War of the Planet of the Apes, Wind River, Wonder

Woman, Your Name.

Worst of the year (runners-up):

Good Time (Josh and Benny Safrie)

I Do… Until I Don’t (Lake Bell)

Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the

White House (Peter Landesman)

Worst of the year, a

movie that absolutely earned its lower-case representation:

mother! (Darren Aronofsky)

When I “saw” mother! on its theatrical release, I

said that I would suggest it was “one of the silliest, most masochistic,

self-aggrandizing allegories/fantasies ever committed to film (or pixels, or

whatever)—the Artist as All-Demanding, Relentlessly Punishing Deity and

Universe-Sized Megalomaniacal Creator Whose Supplicants Are Not Worthy of Him--

but unfortunately, beyond the general hysteria and cacophony and gooey vaginal

floorboard gouges and piles of bloody-pulp-rendered sacrificial lambs, I can’t

be entirely sure of what I even saw.” And that kicked off an account of one of the worst nights I've ever spent in a movie theater. So before deciding to cement Darren

Aronofsky’s ludicrous vanity puzzle at the bottom of my list, I decided to

watch it again on Blu-ray. Let’s just say, a second helping did not help.

MOVIES I CAUGHT UP WITH FOR THE VERY FIRST TIME IN 2017

Alibi Ike (1935; Ray Enright)

All Screwed Up (1974; Lina Wertmuller)

Anatahan (1953; Josef von Sternberg)

The Bandit Trail (1941; Edward Killy)

The Band Wagon (1953; Vincente Minnelli)

Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979; Irwin Allen)

The Breaking Point (1950; Michael Curtiz)

Chisum (1970; Andrew V. McLaglen)

A Christmas Carol (1938; Edwin L. Marin)

Countdown (1967; Robert Altman)

Crossfire (1947; Edward Dmytryk)

Curse of the Faceless Man (1958; Edward L. Cahn)

Dames (1934; Ray Enright, Busby Berkeley)

Daughter of Dracula (Le Fille de Dracula)

(1972; Jess Franco)

A Day in the Country (1936; Jean Renoir)

Downhill Racer (1969; Michael Ritchie)

Dynamite Pass (1950; Lew Landers)

The Earth Dies Screaming (1964; Terence Fisher)

The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-moon Marigolds (1972; Paul Newman)

Fallen Angel (1945; Otto Preminger)

Five Came Back (1939; John Farrow)

High Wall (1947; Curtis Bernhardt)

Hit Man (1972; George Armitage)

How to Steal a Million (1966; William Wyler)

Island of Lost Women (1959; Frank Tuttle)

Jigoku (1960; Nobuo Nakagawa)

Kill, Baby… Kill! (1966; Mario Bava)

King of Jazz (1930; John Murray Anderson)

The L-Shaped Room (1962; Bryan Forbes)

Leo the Last (1970; John Boorman)

Love Crazy (1941; Jack Conway)

The Lusty Men (1952; Nicholas Ray)

Miranda (1948; Ken Annakin)

Murder Ahoy (1964; George Pollock)

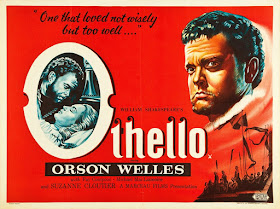

Othello (1951; Orson Welles)

Outrage (1950; Ida Lupino)

Panique (1946; Julien Duvivier)

The Reptile (1966; John Gilling)

Robin and Marian (1974; Richard Lester)

Run for the Sun (1956; Roy Boulting)

Rustlers (1949; Lesley Selander)

Scream, Blacula, Scream (1973; Bob Kelljan)

Son of Godzilla (1967; Jun Fukuda)

The Stone Killer (1973; Michael Winner)

Summer Night with Greek Profile, Almond Eyes and Scent of Basil (1986; Lina

Wertmuller)

Those Redheads from Seattle (1953; Lewis R. Foster)

Terminal Island (1973; Stephanie Rothman)

Unholy Rollers (1972; Vernon Zimmerman)

The Underworld Story (1950; Cy Endfield)

Villain (1971; Michael Tuchner)

Visions of Eight (1973; Milos Forman, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch,

Yuriy Ozerov; Arthur Penn, Michael Pfleghar; John Schlesinger, Mai Zetterling)

Yuriy Ozerov; Arthur Penn, Michael Pfleghar; John Schlesinger, Mai Zetterling)

Wagon Train (1940; Edward Killy)

Way Out West (1937; James W. Horne)

While the City Sleeps (1956; Fritz Lang)

Woman of the Year (1942; George Stevens)

The World’s Greatest Sinner (1962; Timothy Carey)

MY BEST MOVIEGOING EXPERIENCES OF THE YEAR

As almost always of

late, my favorite moviegoing experiences usually involve my oldest daughter

Emma, who will turn 18 in a couple of months. She’s turned out to be the big

movie fan of my two, ensuring that I will never have to go through the

near-complete rejection of values that I put my own outdoorsman dad through

when I was a bookish, nerdy teen. And she is always up for adventure. We took

in the opening weekend of Wonder Woman together

in our favorite seats at the Vista Theater in Hollywood—it was quite a thrill

to watch the movie with her, and to watch her watch the movie and appreciate

the pleasures of superhero gender turnabout that the movie had to offer. For

all the heroics and assertion of female empowerment, I think our favorite scene

was Diana making her way through the streets of London, discovering ice cream

for the first time and gushing over it to the modest vendor— "You should be very proud!")

We also thrilled

memorably to Thor: Ragnarok, The Shape of

Water and, on a particularly dreary post-holiday evening when we were both

feeling a little down, Jumanji: Welcome

to the Jungle, an evening out with a silly movie that did us both a

universe of good. We also tread the darkest part of the night together for a

packed-house midnight screening of Akira,

which may have impressed me even more than it did her.

Chucky, everyone’s

favorite diminutive, quite plastic, and thoroughly deadly doll gave us perhaps

our most unforgettable moviegoing evenings together this year, however. Joined

by my best friend Bruce and little sister Nonie, we took in Don Mancini’s

brand-new dose of mayhem, Cult of Chucky, together, a one-time-only theatrical screening

hosted by Maestro Mancini himself. C of C

is, to my mind anyway, the horror movie of the year, and it was a thrill to be

one of the few, along with my daughters and my best pal, to get to see it this

way.

But even better than

that was the Bride of Chucky/Seed of

Chucky screening we attended a month or so before that, which had as its

centerpiece a bawdy and hilarious Q&A featuring, among others, Mancini,

Jennifer Tilly and Billy Boyd, the actor who memorably portrayed Pippin in The Lord of the Rings’ trilogy and, more

importantly for Emma, voiced the character of Chucky and Tiffany’s

gender-confused son, Glen (or Glenda). Glen (or Glenda) is easily Emma’s

favorite character in her favorite Chucky movie, and she was abashed with

excitement at just being able to see him on stage. But when beforehand I hinted

to Don just how excited she was, he went the extra mile and introduced Billy to

Emma from the stage! She was as

thrilled as any mortified teen could possibly be, and even more so when, upon

leaving the stage before the movie began, the infectiously friendly actor

stopped by our seat to personally say hello again. And I got it all on my

trusty phone. What a night!

Two great theatrical screenings stand out for me over the course of the year: the first is seeing Michael Ritchie’s Prime Cut as the opening night salvo of UCLA Film & Television Archive’s August series of films culled from critic Charles Taylor’s book of essays entitled Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-in Near You. Taylor was there at the screening, interviewed by Los Angeles Times film critic extraordinaire Justin Chang, and in addition to seeing Ritchie’s terrific pulp artifact on the big screen, I got to meet both Taylor and Chang for the first time. Memorable, indeed.

The second came during the opening weekend of AFI Fest 2017-- a rare screening of a pristine 35mm print of McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which I’d never seen projected before (except in 16mm, which, believe me, I don’t count). It was an evening made even nicer by the attendance of Rene Auberjoinois, Altman stock player from the early ‘70s who plays squirrelly local businessman Sheehan in the film. During the brief Q&A that followed the screening, I even got to engage with Auberjoinois re another favorite Altman appearance, his bizarre turn as a professor who, over the course of the movie, morphs into a bird in Brewster McCloud, one of the Altman that, upon encountering in early in my college career, turned me from a merely interested observer into a genuine budding Altmanophile.

As for me on my own,

the most thrilling discovery of a classic film had to be experiencing Nicholas

Ray’s The Lusty Men for the first

time. The year’s best rediscovery

came via Criterion’s exceptionally lovely Blu-ray of Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (bonus: English

subtitles provided by myself and my dear wife!), which seems now clearly, if it

wasn’t before, to be one of the director’s finest works. At home my eyes

popped, for completely different reasons in all three cases, to the Blu-ray of Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets,

Walter Hill’s magnificently outrageous The Assignment, and my first late-night encounter with the utterly

deranged, demonically inspired The

World’s Greatest Sinner, a career-defining showcase like no other for

writer-director-star Timothy Carey. (Thanks, TCM Underground!)

But by far the best

came one evening when, left to my own devices when the women went out for the

evening, I made up a big bowl of popcorn, a homemade dinner and a tall glass of

Diet Coke and luxuriated in the five-hour version of Wim Wenders’ gorgeously

indulgent science-fiction obsession Until

the End of the World, a movie made in 1991 which locates with unnerving

prescience our current addiction to imagery and theories of connection. Wenders

is the director who may have most precisely defined (or redefined) the road

movie with his German New Wave masterpiece Kings

of the Road and, later, his film (based on Sam Shepard’s screenplay) Paris, Texas, and Until the End of the World is probably, among many other things, his

most piercing, technologically infused engagement with the themes of haunted

wanderlust. In it’s five-hour version it’s unlike any movie I’ve ever seen, one

to be absorbed into, to be approached on its own unhurried, exploratory terms.

Seeing it was a revelation, one that may end up forcing me to extend my

satellite subscription for fear of the moment of having to give up the DVR on

which it is recorded. Seek it out, if you can.

Okay, that’s 2017 for

me. Here’s to better fortunes for us all in 2018, including a wealth of new

movies by which to be enriched and enthralled. Now I’m off to continue reading,

along with everybody else, Fire and Fury,

one book to which I hope there will never be a need for a sequel. Cheers!

*****************************************

Hey Dennis,

ReplyDeleteI first saw the five-hour version of "Until the End of the World" in 1998 when Wim Wenders brought his personal print to Seattle (at the time it was called "Until the End of the World: The Trilogy"). I've seen it twice since: once on import DVD, once again on the big screen at NWFF, but nothing approached the joy of that first epic screening. It's not Wenders' best film even in long form but it has been a glorious experience every time.

Happy New Year, Dennis.

So how did you see The Lusty Men? I'm still trying to find a copy, since I'm trying to work my way thru Nicholas Ray movies.

ReplyDeleteHoward, I picked up The Lusty Men on my DVR off of a recent TCM broadcast. It was, until recently at least, available on DVD through Warner Archives, but a quick search there just now reveals that it seems to have been discontinued. I bet you could find a new or used copy online pretty easily though. One thing's for sure-- it's well worth the time and effort to search it up!

ReplyDeleteDennis...thanks...I've watching it on Ebay...fingers crossed I can find a copy.

ReplyDeleteI saw you also saw Chisum and The Breaking Point for the first time this year. Chisum is my favorite Wayne, though I know it's not his best movie. I think it's because of when I saw it...and it seems like it's just "Wayne".

Wife and I watched The Breaking Point since it's another variation of Hemingway's To Have and Have Not (and actually a much better movie than the Hawks!). I now want to see The Gun Runners to compare.

I liked Chisum too, although it may have more to do with reasons of nostalgia than for filmmaking-- I'll never forget the rush of excitement going through my junior high about the John Wayne movie where the guy (Forrest Tucker) ends up impaled on a longhorn rack!

ReplyDeleteAnd I felt the same way about Hawks vs. Curtiz re To Have and Have Not and The Breaking Point. I was bowled over by The breaking Point, and it really does make Hawks' take seem slight by comparison. Thanks for the reminder about the Don Siegel version too-- I'd completely forgotten about it!