“You mean to tell me my uncle actually charged people to go

in there? And people actually paid?” –Matt Spenser (Bill Travers) upon first seeing the condition

of the Bijou Kinema, in The Smallest Show

on Earth

In Basil Dearden’s charming and wistful 1957 British comedy The Smallest Show on Earth (also known

under the far-less evocative title Big

Time Operators), a young couple, played by Virginia McKenna and Bill

Travers, inherit a small–town cinema, the Bijou Kinema-- known to the citizenry

of Sloughborough as the Flea Pit-- and decide, in order to drive up the selling

price to the local cinema magnate, who wants to tear it down and build a

carpark, that against all odds and common sense they’ll reopen the doors and

give the business a go. They also inherit three elderly employees who have long

been part of the Bijou’s checkered history—Mrs. Fazackalee (Margaret

Rutherford), the cashier who was once also the cinema organist during the

silent era; Mr. Quill (Peter Sellers), the projectionist with a more-than-slight

penchant for Dewar’s White Label; and Old Tom (Bernard Miles), the janitor who

only wants a uniform commensurate with his position and who dutifully provides

a fiery solution when negotiations with the magnate hit a snag. These three

comprise what passes for the barely beating heart of the Bijou, and if

Dearden’s movie seems to end just as the third act is set to begin, it remains

a sweet-tempered testament to the blinkered spirits of the Bijou staff, as well

as to the fleeting pleasures of nostalgia and the long-lost palaces where past

generations learned to love the movies.

Some of the richest comic highlights of The Smallest Show on Earth come from all the technical foul-ups

that come courtesy of the theater’s antiquated equipment—busted reels, focus

failures, upside-down images and, of course, the image of sizzling celluloid

from a frame on fire, these are as good as a cartoon and a newsreel, the

expected bonuses when you buy a ticket at the Bijou. And audiences in 2015 who

stumble upon this little beauty on DVD (or on Amazon Streaming

Video, where it is currently available) will likely get huge laughs from the movie’s sly comment on the panicked

movie industry’s attempt to stave off the deleterious effects of television

through unabashed gimmickry.

Unable to afford upgrades to Cinemascope and stereophonic

sound, the staff at the Bijou make do (albeit inadvertently) with the hardships

imposed on them by the march of progress.

One of the factors of modernity contributing to the theater’s fall into

disrepair is a railway which zooms directly past the outside of the auditorium,

making the building shake from its faulty foundation to its rickety rafters. However,

fortune smiles upon the Spensers as audiences react with wild abandon when the

roar of the train outside is accidentally synched to a scene of a train robbery

in the western on screen. The rumbling is so awful that poor Mr. Quill,

recently having “taken the pledge,” is driven back to drink after throwing

himself bodily on the projector to keep it from vibrating off its floor mounts.

But the audience sees it as an “enhanced” experience, something they certainly

couldn’t get from sitting at home in front of the tube.

Viewers taking in The

Smallest Show on Earth 60 years later will think of everything from

Sensurround to D-Box, technological gimmicks that, effective as they might be,

still probably wouldn’t be as much fun as a well-timed passing locomotive

threatening to literally bring the house down. The movie gently satirizes the

raucous behavior of working-class audiences in the age of television while

serving as a bridge between the rapidly changing landscape of modern

entertainment and its own unapologetically nostalgic yearning for days past,

when tastes were simpler and ornate palaces built to showcase flickering images

of grandeur and adventure were commonplace. Whatever else you might say about

them, the rowdy, television-spoiled audiences that (eventually) pack the Bijou

are at least having fun, unlike their “sophisticated” modern-day counterparts,

whose countenances, lit by cell phone screens, betray the desultory sense that,

despite the fact that they’ve paid upwards of $13 to get in, they’d rather be

anywhere else than in a theater watching a movie.

Of course, that appeal to nostalgia for days past rings slightly

differently in 2015 than it did for the characters in Dearden’s film, who have

seen change in the film industry, from silent to sound to color to wide-screen,

but who mourn most especially for the days when the theater could be packed for

every show, when the movies really were the best and only show in town.

Audiences exposed to the movie today might first marvel that there were ever

such huge, expansive, ornately designed, single-screen temples whose only

purpose was to show movies. Modern multiplexes with 25 screens and a bounty of

tentpole blockbusters to exhibit still find themselves appealing to Internet

technology to stimulate ticket sales, booking live, high-definition video feeds

of operas and other “special events,” and even appealing to organizations like

churches to rent auditoriums, all in order to stay afloat in an age when

entertainment choices are even more fragmented. Single-screen palaces for

everyday exhibition really are, with a few exceptions like the historic Vista in East Hollywood, things of the past.

For me, seeing The Smallest Show on Earth for the first time in 2014 provided its own sort of coincidence, like a train with the word “progress” spray-painted on its engine in ironic quotation marks rumbling past, but without the pleasant afterglow of an enhanced experience. As I watched the efforts of the Spensers and their staff to raise the Bijou Kinema from the ashes, I couldn’t help but reflect on a couple of beloved movie palaces in my own life that are not now what they once were. In September it was announced that the New Beverly Cinema was being taken over by Oscar-winning filmmaker Quentin Tarantino and that Michael Torgan was out. (Torgan took over daily operation of the theater when his father Sherman, who opened the theater as a repertory cinema in 1978, died unexpectedly in 2007.) Not much more is known now about the specifics of what transpired than when the coup was announced in Late August, other than it seems to have been precipitated by Torgan’s purchase of a digital projector, to which his notoriously 35mm-or-nothing landlord took extreme exception. In solidarity with Michael, and out of indifference to the heavily Grindhouse-tilted tenor of the programming since the theater reopened in October, I have yet to return to the New Beverly, and I really miss it. Recent reports have it that Torgan has indeed returned in some capacity—a friend saw him in the box office recently, and also changing the marquee on an early Saturday morning—so I suspect that sometime soon I will be back. Though it’s hard to imagine that the vibe won’t somehow be changed, different, at least the New Beverly is still showing films, one of several tantalizing daily options Los Angeles moviegoers have on the revival cinema scene.

For me, seeing The Smallest Show on Earth for the first time in 2014 provided its own sort of coincidence, like a train with the word “progress” spray-painted on its engine in ironic quotation marks rumbling past, but without the pleasant afterglow of an enhanced experience. As I watched the efforts of the Spensers and their staff to raise the Bijou Kinema from the ashes, I couldn’t help but reflect on a couple of beloved movie palaces in my own life that are not now what they once were. In September it was announced that the New Beverly Cinema was being taken over by Oscar-winning filmmaker Quentin Tarantino and that Michael Torgan was out. (Torgan took over daily operation of the theater when his father Sherman, who opened the theater as a repertory cinema in 1978, died unexpectedly in 2007.) Not much more is known now about the specifics of what transpired than when the coup was announced in Late August, other than it seems to have been precipitated by Torgan’s purchase of a digital projector, to which his notoriously 35mm-or-nothing landlord took extreme exception. In solidarity with Michael, and out of indifference to the heavily Grindhouse-tilted tenor of the programming since the theater reopened in October, I have yet to return to the New Beverly, and I really miss it. Recent reports have it that Torgan has indeed returned in some capacity—a friend saw him in the box office recently, and also changing the marquee on an early Saturday morning—so I suspect that sometime soon I will be back. Though it’s hard to imagine that the vibe won’t somehow be changed, different, at least the New Beverly is still showing films, one of several tantalizing daily options Los Angeles moviegoers have on the revival cinema scene.

More pointedly, however, 2014 was the year that the movie palace

of my own childhood finally closed its doors for what looks like the last time.

I saw my very first movie in a theater at the tender age of three. It was Gay Purr-ee (1963), the Abe

Levitow-directed animated feature (co-written by Chuck Jones) about cats in the

French countryside making their way to the big city, and I saw it at the Marius

Theater in beautiful downtown Lakeview, Oregon. The Marius, built in the early

1930s, wasn’t the first movie theater in town—there was a tiny silent

theater operating in the early 1900s that introduced the industrial age wonder

of the movies to the Irish immigrants and cowpokes who first populated my hometown.

(Writer Bob Barry commemorated the theater, whose name I can’t recall—the Rex,

maybe?—in his book of local history From Shamrocks to Sagebrush.) But the Marius was my first. I

don’t remember a thing about it, and without the help of some photographs I

doubt I’d even be able to recall what the exterior looked like—it was closed

and remodeled into an office building during the years in the mid-60's when my

family briefly moved to California. By the time we returned in 1968, the Marius

was gone. (The remnants of the theater stage are still discernible in the

basement of that remodeled building, known since the theater’s closing as the

Marius Building. Otherwise, you'd never know a movie theater once stood there.)

By the time I returned to Lakeview in 1968, I’d been

infected by the movie virus in a serious way. My parents took us to movies at

the big theaters near the outskirts of Sacramento—the Tower and the Roseville

in downtown Roseville, and the Citrus Heights Drive-in in the bedroom community

of Citrus Heights, where we lived—and when we moved back to the rural splendor

of Lakeview, I took as full advantage as I could of the opportunity to go to

the movies by myself or with friends—something we weren’t allowed to do in the

big city. And the Alger Theater, at the edge of downtown Lakeview, just a mile

from my house, became my refuge, my oasis, my home away from home. Those were

the days of double features, Saturday matinees (with reduced prices!), of

driving into town and thrilling to see the lights of the marquee turned on

before sundown, beckoning, promising a peek into a world well beyond the limits

of what could be offered by my little burg. I dreamt of that place often, the

yellow bulb lights dotting the undercarriage of the marquee, glowing and

playing off the pale green trim of the theater frontage—it was glamorous, the

only glamour my town had to offer, and it was irresistible.

My dad’s side of the family, the Italians, were dutiful

Catholics, and as such were well acquainted with Bob and Norene Alger, visible participants in local Catholic culture who

owned and operated the Alger Theater and the Circle JM Drive-in Theater on the

north end of town—they had owned the Marius as well. Being the son (and grandson) of

family friends, Mr. and Mrs. Alger always made me feel welcome. I can remember

filing out of many matinees and evening shows and being greeted by Mrs. Alger

with a hug, which many of my friends and peers thought was strange because she

was rarely any more than standoffish—and sometimes downright cranky—to most of

them. She also came down into the auditorium to personally check on me the

night I first saw Blazing Saddles,

apparently fearing from my relentless laughter that I was in danger of respiratory

failure or full-on hysteria. And the very first review I ever wrote, at the

tender age of 12, came at the behest of Mr. Alger, who offered me free

admittance to the Saturday night showing of Young

Winston (1972) if I would provide him a written review of it after mass

the following morning. I have no idea why he wanted me to write about it, but I

did. When I handed over my little essay, he accepted it with that slightly

inscrutable half-smile, which could be easily misinterpreted (or correctly interpreted,

I suppose) as a frown and which rarely left his face. I never heard another

word about the review, and he never asked me to do it again.

Though they were overseers of one of the two primary

communal entertainment options available to Lakeview back in the day, Bob and Norene felt

no need to worry about competing with television. Which was a good thing,

because the Algers were anything but show people. They ran the theater with an

increasing sense of begrudging duty, and not without a sense— definitely noticed

by the general populace— that they were too socially sophisticated for the

audience they served. And they didn’t go in for gimmicks or promotions either. The only bonuses

offered by the theater came on Christmas Eve (an annual canned food drive

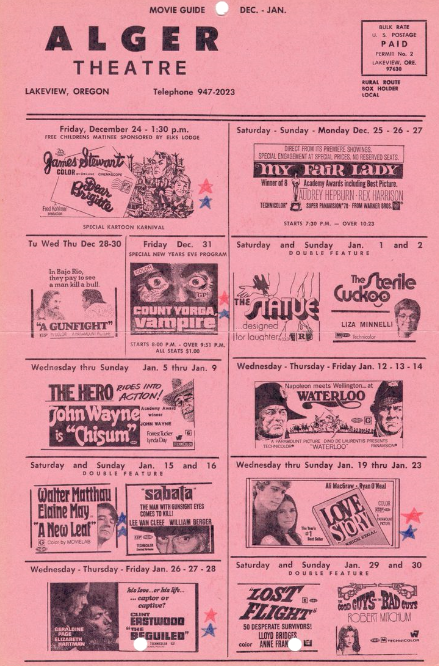

matinee which didn’t survive the early ‘70's-- see Dear Brigitte on the calendar to the left); Independence Day (a bare-bones

fireworks show for which several pals, including the Algers' son David and I, comprised the mortar crew when I was

a teenager); and, best of all, one-night horror shows for New Year’s Eve,

Halloween and whenever a Friday the 13th would roll around. The

Alger booked a terrific array of Hammer, Amicus and American-International

titles for my formative years, allowing me to see films like Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, Dracula Has

Risen from the Grave, Rasputin the Mad Monk, The Fearless Vampire Killers, The

Green Slime, Tales from the Crypt, Asylum, The House That Dripped Blood, Count

Yorga, Vampire and countless others that stand as favorites to this day,

all projected to a crowd of very enthusiastic screamers.

Audiences at the Alger weren’t far removed from the hijinks

of those rowdy delinquents inside the Spensers’ Bijou either. One of the apocryphal Bob Alger stories for

me and my buddies came as a result of a Halloween night screening of Tales from the Crypt during which the

audience, comprised mostly of high school kids like myself who, unlike myself,

were there to do anything but watch the movie, got well out of control. The din started before the

opening curtain and continued to increase. And when some sort of projectile

flew out of the crowd and landed very close to the screen, it wasn’t long

before Mr. Alger marched slowly, deliberately, to the front of the theater, the

lights came up, the movie stopped and everyone went silent. “What I have before

me, on the floor of the auditorium,” he intoned ominously, as fearsome as Sir Ralph Richardson's cryptkeeper, “is a fresh egg.” He

berated the audience for their behavior and threatened to shut the screening

down entirely, with no refunds, if decorum wasn’t restored immediately. He even

yelled out at one poor bastard who was still cutting up during his speech—“You!

In the balcony! I know it was you who threw it!” Even though I wasn’t causing

trouble myself, I was terrified (I could only laugh about it later), but I was

also secretly glad because, goddamn it, I couldn’t hear the movie, and the last

thing I would have wanted was for the Algers to pull the plug on these horror

holiday special shows, which I considered a major perk and a significant

antidote to the doldrums of Lakeview citizenship.

I went to see everything I could at the Alger. I wanted to see everything I could. But for the general audiences, who during the early 70s came out to see just about anything the theater showed—I remember a half full house for Buffalo Bill and the Indians, for crying out loud, a phenomenon probably attributable to the cowboy community assuming they were in for a run-of-the-mill western—I don’t think the movies themselves mattered nearly as much as the chance to get out and do something, anything. And when that movie was done, it was done—there was no going out and talking about it afterward, because movies were rarely seen as anything more than simple diversion. And sometimes the movie was done before it was done. One of the funniest moments in The Smallest Show on Earth comes as a B-western is beginning to wrap up. It’s the last scene in the movie, and the audience, sensing that the meat of the action has finished, jumps up and bolts for the exits before “The End” even has a chance to pop up and cue them that it’s time to leave. The audiences at the Alger were similarly inclined to get on with life rather than savor the cinematic experience they’d just had. I’ll never forget coming home from college and seeing Star Wars with the hometown crowd. As soon as the Death Star exploded, at least 40 people in the packed house grabbed their coats and scooted out of the theater.

For all its deficiencies—the inept projection, the frequently misspelled marquee (it was always “Pual” Newman in something or other, and I’ll never forget “Ward Bond 007” in The Man with the Golden Gun), the uncomfortable seats, the indifferent management—the Alger was where I really fell in love with the movies. That love would be deepened elsewhere, but the Alger's lights always seemed to be visible to me from the dark quiet of Southern Oregon nights long after I’d left the town, a glowing reminder of where it all began.

The Algers closed the drive-in in 1981 after a winter storm ripped the screen in half like a piece of paper. They kept the indoor theater open for a couple years after that, but soon retired, and it sat dark for a few months during the early ‘80s, when local folks were finally getting into the swing of the VCR era. It eventually reopened under new ownership in the mid-80s, and competition to keep pace with an ever-shrinking window between theatrical release and home video debut forced the theater to begin picking up releases much more quickly than it ever did under the guidance of Bob Alger. In those days, it wasn’t unusual to have to wait 6-9 months after its national release for a movie to bow at the Alger—Jaws played at the Circle JM Drive-in during the summer… of 1976. But the video-age Alger was facing a much changed exhibition landscape. I remember being completely shocked to open up the pages of the local weekly newspaper, the Lake County Examiner, 15 years ago and seeing a tiny ad for the week’s offering at the Alger, Scream 3, which was opening at the Alger the very same night it opened on 3,000 or so other screens across the nation, an unthinkable scenario even five years before then.

(These photos of the Alger Theater date from about one to two years after its opening. Above, Gene Autry in Sierra Sue and All-American Coed were both released in 1941, and despite the "1938" notation on the lower photo, given the release date of Alfred Hitchcock's Saboteur, the feature advertised on the marquee, the date of this photo is likely sometime after 1942.)

The theater, under new management now twice removed from Bob and Norene Alger, more or less limped into the digital age. Shows were now weekends only, and the theater, which opened in 1940 (see photos above), was beginning to show the effects of a lack of cosmetic upkeep. A ghastly stage had been installed in the mid ‘80s, ostensibly in a move to establish a community theater which never took hold, the stage obliterating the first four or five rows of original seats. What seats remained were the original 1940 editions and as butt-numbing as ever; the marquee lights were spotty, every other bulb either burnt out or screwed into a socket that had long since failed to carry current; the façade of the theater was tattered and badly in need of a paint job; and the marquee itself was warped, rickety and weather-beaten, its ability to hold up plastic letters routinely challenged by a stiff breeze. With the cost of keeping the theater open for just three days a week becoming increasingly indomitable, it seemed the writing was on the wall, and it probably had been for at least the first 10 years of the 21st century.

Much like how the storm that destroyed the drive-in screen in 1981 had presented the Algers a convenient exeunt from the drive-in business, big studio threats to stop providing 35mm prints to theaters, thus forcing small-town operations like the Alger to upgrade to digital equipment in order to stay in business, were the rationale current management needed to call theatrical exhibition in Lakeview, Oregon a permanent day. After several attempts to communicate with the current owners and brainstorm ideas for keeping the theater alive—a theater in nearby Alturas, California, had successfully navigated a crowd-funding campaign to upgrade their theater and make it a community-operated business—I stopped receiving replies to my e-mails, and it became clear that, in response to deteriorating attendance, the owners weren’t really interested in rallying an effort to come up with the money to keep the doors open.

So, in March 2014 the reels of the Alger Theater’s 35mm platter projection system spun their last. The theater, much like Hollywood itself, had long since ceded any attempt to appeal to any other audience beyond the PG/PG-13 market, the only folks left in town who could be counted on to occasionally show up for a movie. It’s grimly appropriate that the last picture show would not be a landmark like Red River (the Alger management likely being unaware of that movie, or The Last Picture Show, for that matter), or even an adult-oriented audience-pleaser like the recent Oscar-winner Argo. Instead, it was the generic animated movie The Nut Job, and a sadder, more ignominious finale I couldn’t possibly imagine. According to a report filed by my niece, who was very upset about the theater closing and tried herself to generate some local interest in preserving it, the last show was just as nondescript and lacking in fanfare as one might expect. The end credits playing before an empty auditorium, what there was of the audience having already listlessly filed out, the marquee lights went dark over South F Street, the main drag on which the Alger held dominance for 74 years, and they haven’t been back on since. It’s not clear as yet whether the township of Lakeview has even noticed.

So, in March 2014 the reels of the Alger Theater’s 35mm platter projection system spun their last. The theater, much like Hollywood itself, had long since ceded any attempt to appeal to any other audience beyond the PG/PG-13 market, the only folks left in town who could be counted on to occasionally show up for a movie. It’s grimly appropriate that the last picture show would not be a landmark like Red River (the Alger management likely being unaware of that movie, or The Last Picture Show, for that matter), or even an adult-oriented audience-pleaser like the recent Oscar-winner Argo. Instead, it was the generic animated movie The Nut Job, and a sadder, more ignominious finale I couldn’t possibly imagine. According to a report filed by my niece, who was very upset about the theater closing and tried herself to generate some local interest in preserving it, the last show was just as nondescript and lacking in fanfare as one might expect. The end credits playing before an empty auditorium, what there was of the audience having already listlessly filed out, the marquee lights went dark over South F Street, the main drag on which the Alger held dominance for 74 years, and they haven’t been back on since. It’s not clear as yet whether the township of Lakeview has even noticed.About two months ago I got a message from a friend still living in Oregon who said she’d heard that the Alger was about to be purchased by a new owner, given a digital upgrade and a paint job, and reopened. Did I dream this? If it were true, it would be an unlikely deus ex machina, given the history of this theater, and given the economic straits in which the town finds itself in 2015. It’s the sort of dream of the past and its familiar faces that I wake up from all the time. But no, I didn’t dream it. The message was real. And whether or not the resurrection of the Alger makes the transition from rumor to reality—and the town’s active interest in making it happen cannot be overemphasized-- will be a story I plan to follow closely over the coming year.

Maybe it doesn’t mean the same thing to the current citizenry of Lakeview that it does to me. Maybe it never did. However they may have felt, it’s difficult for me to discount the importance such a tiny blip on American culture as the Alger had on the forming of my mind and my desire to see more than what could be offered on the dusty, muddy streets passing outside its doors. If they’re lucky, everyone reading this will have a place like it nestled in their memories, a place where love for what the movies could show us, could inspire in us, the emotions they could stir, was instilled and made foundation for the appreciation of what movies could be that we had yet to understand. When I see the empty shell of that theater, standing abandoned and ignored at the edge of my hometown, I don’t feel like a piece of me is lost. No, I know right where that piece is at. It’s still inside those doors, in communion with the dusty old red curtain, the forever dimmed house lights running the edges of the auditorium at the ceiling level, the mysterious projection room, from whence all those amazing sights and sounds emerged, the tidy confines of the snack bar, watched over by the old Thornton’s Drug clock on the wall, its timekeeping partner, the one bearing the Lincecum Signs ad, still perched in the auditorium above the door to the back of the screen, stage left. Yep, I’m still in there, sitting in those worn-down seats, waiting for the next movie to start. By a great stroke of fortune, maybe someday it will.

********************************************************

A GALLERY OF SHOTS FROM MY FINAL VISIT TO THE ALGER, SUMMER 2013, AND DURING THE DAYS AFTER ITS CLOSING

(Thanks to Kamaryn Schneider for some of these images, above and below.)

*********************************************

If Julia is rehired, I'll go back to the New Beverly.

ReplyDeleteA New Leaf and Sabata -- there's a double bill.

ReplyDeleteI've been to the New Beverly a couple of times since the coup, though I won't deny the bad taste in my mouth. The hell of it is, if it had been in addition to rather than instead of the genuine New Beverly you'd have said it was a valuable addition to repertory film programming in L.A., but it's an inadequate replacement for the kind of encyclopedic programming of the original. It gets like junk food for dinner every night with a steak thrown in now and then. Under ideal conditions I would really enjoy the cinematic found objects Tarantino throws in between the features, but thinking of where it comes from brings back the bad taste in the mouth.

The reason I went firstly is that I wanted to see Hickey and Boggs again, the previous time being during its first run. Back then I was disappointed because it wasn't I Spy. Seeing it without those expectations, I figure in its time it must have looked like a poor man's Dirty Harry, and that's what it looks like now. In going to this show I was of course not only violating the Tarantino New Beverly taboo but the Cosby taboo as well. I find the accusations credible, I'm sure he fully deserves the anguish he's being put through, but you know, I still love the guy. The show included some contemporaneous concert and promotional film, which only underscored the impression that there was something fucked up about Cosby during that Mother, Jugs & Speed period. And I want to emphasize this was an impression I had long before I heard of rohypnol. You just had to see that scene where he's sitting in that ambulance drinking a beer with that look on his face that said, "I'm fucking dead already." Not that this is an excuse at all, but I think this was not a man who was cut out for L.A.

The other time I had to go because they were showing The Exile, the last Hollywood Ophuls I hadn't seen. This was part of a serendipitous Ophuls weekend, as I'd been to LACMA the Friday before to see Letter from an Unknown Woman and Liebelei. This was an experience I'd hadn't had in a long time, seeing two movies on a revival bill I'd never seen before. This was a feeling I've missed. You get to a certain age an you realize that you've seen most of your personal want list. Next to In a Lonely Place, Letter from an Unknown Woman must be most un-Hollywood movie ever made under the studio system.

As for the return of Torgan, that was something I about 75% expected. I 100% expected that Tarantino was going to get tired of playing theater owner at some point, and the 25% uncertainty that he'd bring Torgan back was mainly whether pride would get in the way at either end. I only hope that Tarantino is so desperate to get out of it that he'll let Torgan use the digital projector if he wants to. He'd probably make a better living on salary than as owner. I'd been tempted to go to the Boetticher double bill, and maybe I can do it with a clear conscience now.

Wow, what a coincidence! Like the author, I spent my youth in Lakeview - I saw Gone With The Wind for the first time at the Maurius. And now, living just a few miles away from the Sacramento area, I am also familiar with the theaters mentioned by the author in Roseville, Sacramento, etc. And while I never got to see the inside of the Algers - it was closed when I lived there and closed for the second time when I returned to visit - but it was always there whenever you went anywhere in town. It would be great to see it reopened and restored and preserved. Someday maybe I too can return to Lakeview.

ReplyDeleteI grew up in Lakeview and had the honor of working for Bob and Noreen at both the Alger Theater and the Circle JM Drive-in. It was great fun and they taught us a lot ...great bosses !

ReplyDeleteI miss going to the movies :(. We have to travel 100 miles to see one. We not only watched movies in Alger theatre, but we used it for dance recitals. It is sad seeing many business close. If only I had the money :) .

ReplyDeleteI love your blog. I am just starting out and would be very grateful if you would take a gander at mine. Thanks so much! http://thefinestthingsclub.blogspot.com

ReplyDelete