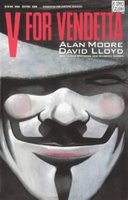

V For Vendetta is, unless I'm forgetting or simply unaware of something fairly obvious, Hollywood's first shot at adapting a comic book (or graphic novel, if you must) that features its political content rather than its action set pieces front and center. I'm only just getting into Alan Moore's original book, but it's already fairly clear to me that one of the shakiest wires upon which the film must balance is the one from which the "superhero" element of the story must be served without watering down or rendering hopelessly silly that political content. The hyperstylized world of Moore's novel, illustrated by David Lloyd, allows, as most comic books must, for Herculean suspension of disbelief arrived at, once the graphic novel format is accepted, fairly easily. The movie, which takes place in three-dimensional space, has the same protagonist-- a terrorist operating beneath a Guy Fawkes mask who works to enact vengeance upon and otherwise render to smoking ruins the corrupt British totalitarian state in which he dwells. But in acting out scenarios that might play perfectly well on the page, the filmmakers-- any filmmakers-- risk throwing their intended tone completely off the scale with the slightest misstep.

V For Vendetta is, unless I'm forgetting or simply unaware of something fairly obvious, Hollywood's first shot at adapting a comic book (or graphic novel, if you must) that features its political content rather than its action set pieces front and center. I'm only just getting into Alan Moore's original book, but it's already fairly clear to me that one of the shakiest wires upon which the film must balance is the one from which the "superhero" element of the story must be served without watering down or rendering hopelessly silly that political content. The hyperstylized world of Moore's novel, illustrated by David Lloyd, allows, as most comic books must, for Herculean suspension of disbelief arrived at, once the graphic novel format is accepted, fairly easily. The movie, which takes place in three-dimensional space, has the same protagonist-- a terrorist operating beneath a Guy Fawkes mask who works to enact vengeance upon and otherwise render to smoking ruins the corrupt British totalitarian state in which he dwells. But in acting out scenarios that might play perfectly well on the page, the filmmakers-- any filmmakers-- risk throwing their intended tone completely off the scale with the slightest misstep.It's a relief to report that, despite occasional lapses in that tonal balance, V For Vendetta is a strikingly successful achievement, a personal epic that risks alienating its audience by not delivering big action set pieces with metronomic regularity, by liberally dosing them with literary (and, in V's first big on-screen speech, giddily alliterative) allusions, and asking them to identify, in the post 9-11 world, with a "hero" for whom large-scale destruction and small-scale retribution are the only effective tools. It's a relief to experience a movie that doesn't shy away from the most troubling implications of its hero's actions, but instead uses them to not only stir up the audience's emotions but to also get them thinking about why they're reacting the way they are to acts which, in slightly different contexts, could be looked upon not as heroically revolutionary but instead simply destructive, possibly murderous. Of course, the raison d'etre for director James McTeigue and screenwriters Andy and Larry Wachowski in updating Moore's book from its Thatcherian roots (a move that has not pleased the notoriously dyspeptic author) is to encourage the perception of similarities between the repressive, dictatorial regime depicted in the film and the current climate created by waging an increasingly unpopular war for trumped-up or blatantly false reasons and the squandering of civil liberties in the name of national security that have been hallmarks of the post-9/11 Bush administration. V For Vendetta is being released into the world under the auspices of one of those giant corporations-- Time-Warner-- whose interests are of prime importance to those currently in power. But that hasn't dulled the filmmakers' instincts to bite the hand, or attack the sensibilities, of that which feeds them. They've delivered an incendiary entertainment that isn't satisfied with just mounting a vision of a dystopian nightmare-- the avenger V wants his revenge and to kick-start a new order, but he also wants his young charge, the initially politically neutral Evey, to connect the dots back to the roots of that nightmare-- our nightmare-- and that's what the filmmakers want us to do too.

V's mask, that of the 17th-century British seditionist Guy Fawkes, never falls away. (Fawkes, a radical Catholic who planned to blow up Parliament, thereby assassinating both houses and King James I, is burned in effigy in England to this day every November 5, the day Fawkes' "Gunpowder Plot" was foiled.) One of the biggest gambles in V For Vendetta is the handing-over of the film's sympathies to such a visually stylized character, effectively robbing the actor who plays him of an essential tool-- his face-- in the seduction of an audience to those sympathies. Fortunately, for us, Hugo Weaving is the man behind the mask, and he disarms a potential disadvantage by using his mellifluous voice and the subtlety of his body movements to convey what his face cannot. His greatest triumph is in creating a constant desire in the audience to see V's true face, and then inspiring us to hope that it is never revealed, for fear of reducing the richness of the mystery the actor has been able to spin from his circumstances. What Weaving does here is a marvel to behold.

As for his costar, I've never been too solidly in Natalie Portman's camp. Though she was perhaps the best thing about Ted Demme's Beautiful Girls, I thought the exploitation she endured under the watchful eye of Luc Besson (and I don't mean that in a responsible guardian kind of way) in The Professional was borderline criminal. But even through her emergence as a star in vehicles like Where The Heart Is, up through her tragically awful sleepwalk through George Lucas' green-screen universe, and even including her Oscar-nominated breakthrough adult role in Closer, I've never thought she was much of an actress. In V For Vendetta, Portman makes a convincing case for herself as a talented actress. Though barely rising above her familiar ingenue status for the film's first half (in the comic book Evey is introduced turning tricks), Portman has never been better than she is here in an extended sequence after Evey has been captured, shorn of her long locks, imprisoned and subjected to what seems like months of interrogation, torture and isolation. The actress and the film have been criticized for not making the politically reborn Evey more of a woman of action. But it seemed realistic to me that she should, even after her radical readjustment, still need time to find her feet, as it were. And Portman compels us through this dark reimagining of Evey's soul with much empathy and admirable fearlessness. She reflects the audience's ambivalence about supporting V's ultimate plan of destruction; we grapple with the implications for the future of the film's Britain right alongside her, while at the same time ruminating upon the revolutionary origins of our own country.

As for his costar, I've never been too solidly in Natalie Portman's camp. Though she was perhaps the best thing about Ted Demme's Beautiful Girls, I thought the exploitation she endured under the watchful eye of Luc Besson (and I don't mean that in a responsible guardian kind of way) in The Professional was borderline criminal. But even through her emergence as a star in vehicles like Where The Heart Is, up through her tragically awful sleepwalk through George Lucas' green-screen universe, and even including her Oscar-nominated breakthrough adult role in Closer, I've never thought she was much of an actress. In V For Vendetta, Portman makes a convincing case for herself as a talented actress. Though barely rising above her familiar ingenue status for the film's first half (in the comic book Evey is introduced turning tricks), Portman has never been better than she is here in an extended sequence after Evey has been captured, shorn of her long locks, imprisoned and subjected to what seems like months of interrogation, torture and isolation. The actress and the film have been criticized for not making the politically reborn Evey more of a woman of action. But it seemed realistic to me that she should, even after her radical readjustment, still need time to find her feet, as it were. And Portman compels us through this dark reimagining of Evey's soul with much empathy and admirable fearlessness. She reflects the audience's ambivalence about supporting V's ultimate plan of destruction; we grapple with the implications for the future of the film's Britain right alongside her, while at the same time ruminating upon the revolutionary origins of our own country.V For Vendetta is by no means perfect. When Evey's friend, a host of a national TV talk show, played by Stephen Fry, stages a brutal satire of dictatorial figurehead John Hurt (seen throughout the film mostly on video monitors invoking the spirit, if not the letter, of 1984's Big Brother), it seems a crucial misstep that he so arrogantly misjudges the dictatorship's willingness to come directly to his home and shut him down permanently. The incident is used to remind Evey of the abduction and execution of her own parents and lay the groundwork for her own imprisonment, but it's a narratively sloppy way to achieve those ends. Fry's character, who functions largely as a safe-and-sane harbor for the fugitive Evey, for all intents and purposes an above-ground mirror version of V, could have easily served as more than just a ill-thought-out plot device. (I'll be interested to see if the comic book makes the same mistake.) And as rich as the film looks (it was photographed by the late Adrian Biddle, who shot Brazil), it risks being written off as pedestrian and flat-footed when compared to the groundbreaking visualization of Frank Miller's Sin City at the hands of shallow cinematic virtuoso Robert Rodriguez.

But the way the scenarists, and in particular director McTeigue, fold in the various levels of back-story is inventive and reflective of the chronologically challenging way stories are told in comic books. The fate of Evey's parents, of V's forced participation in a viral conspiracy which results in hundreds of thousands dead, and his own rebirth by fire, and the fate of a gay actress, whose blissful self-awareness and love are destroyed under the government's brutalizing genocidal thumb, all dovetail with the main narrative line in a feat of unexpected resonance, resulting in several sequences that can only be classified as terrifically assured storytelling and bravura filmmaking. An essentially peripheral gay character, seen only in flashback, provides the film with one of its central metaphors ("God is in the rain") as well as its emotional center. V For Vendetta is a political thriller released by a major studio that openly anchors its representation of the repressed underclass, not to mention its sympathies, to the importance of the everyday life and ultimate fate of a lesbian. Now, that seems pretty radical to me. It's a measure of the film's command that it never loses its power to confound our preconceived notions of political expediency and expression, even at those points when its tone wobbles enough to make us aware of the absurdity of a man swooping through the streets of London in a mask, single-handedly doling out bloody justice and somehow escaping the ever-vigilant electronic surveillance that is the lifeblood of the dictatorship he means to destroy. That's the particular province of the comics, that they can sell such absurdities through the urgency of their imagery. Add to that urgency inspired acting, a nimble directorial touch and a passion to engage in a stream of explosive political currency-- a rarity for a film of any stripe-- and you have V For Vendetta.

But the way the scenarists, and in particular director McTeigue, fold in the various levels of back-story is inventive and reflective of the chronologically challenging way stories are told in comic books. The fate of Evey's parents, of V's forced participation in a viral conspiracy which results in hundreds of thousands dead, and his own rebirth by fire, and the fate of a gay actress, whose blissful self-awareness and love are destroyed under the government's brutalizing genocidal thumb, all dovetail with the main narrative line in a feat of unexpected resonance, resulting in several sequences that can only be classified as terrifically assured storytelling and bravura filmmaking. An essentially peripheral gay character, seen only in flashback, provides the film with one of its central metaphors ("God is in the rain") as well as its emotional center. V For Vendetta is a political thriller released by a major studio that openly anchors its representation of the repressed underclass, not to mention its sympathies, to the importance of the everyday life and ultimate fate of a lesbian. Now, that seems pretty radical to me. It's a measure of the film's command that it never loses its power to confound our preconceived notions of political expediency and expression, even at those points when its tone wobbles enough to make us aware of the absurdity of a man swooping through the streets of London in a mask, single-handedly doling out bloody justice and somehow escaping the ever-vigilant electronic surveillance that is the lifeblood of the dictatorship he means to destroy. That's the particular province of the comics, that they can sell such absurdities through the urgency of their imagery. Add to that urgency inspired acting, a nimble directorial touch and a passion to engage in a stream of explosive political currency-- a rarity for a film of any stripe-- and you have V For Vendetta.(Screenwriter Larry Gross goes deeper into the mystery of V, for those who have seen the film already, in an interesting piece at the Movie City News site.)

Dennis — I also enjoyed V, I thought it was a solid comic-book movie. I read the "graphic novel," if some insist, beforehand, and I easily understoood its nods to fascism and totalitarianism, especially in the Thatcher era in which it was written. But where I disagree with some is in this desperate need to link the movie's political message to the (mis)deeds of the Bush administration. I have no problems making that case, but I just didn't see it in the film. The Wachowskis aren't masters of subtlety. If this is indeed an excorating repudiation of the Bush administration's actions in Iraq and Gitmo, etc., as I've read some critics in describing it, then it is stated poorly and amateurishly. To me, these Bush links happen this way: The moviemakers put out the idea that this is an anti-Bush statement and then many liberal critics/bloggers, understandably looking for any reason to attack the administration and any anti-Bush banner to fly, go to the movie and see in it what they want to. But where is it, literally? It just seems to me to echo the comic book's themes that totalitarian states are bad and suppression of free thought is bad (a long standing sci-fi theme, by the way), but nobody seriously is going to see that much of a link between the fascist milieu of V and the essential freedoms of America. For one thing, we can still get together as a people and elect an alternative to Bush if the Dems would get their head out of Bush's ass and find somebody better than John Kerry or Al Gore. If they don't provide an alternative, we have nobody to blame but ourselves. We have some deep serious questions to ask of our current government, for sure, especially what this new generation of Supreme Court appointments is going to do, but serious issues aren't being dealt with really in this movie. If that's the best they can do in taking on Bush, then the moviemakers and culture chatterers are as hopelessly out-of-touch as the leading lights of the Democratic Party seem to be in fashioning an agenda that could actually convince voters to choose them. Hate to get off on a political thread here, but I believe people should enjoy V on its basic merits, and not try to attach these silly political arguments to it. It only proves that cultural critics (and moviemakers) know little about politics, and less about weaving it into their movies. Steven Spielberg, I'll give credit to. The Wachowskis, nah.

ReplyDeleteI really do think the comic book is better, by the way, but I did like the Wachowskis adding in the Stephen Fry subplot. And Portman was good, too, but they missed the chance to create a sense of succession in her character as Moore did (and he gave a bleaker outlook for change in the long run). Also, they toned down her fear/attraction to V, and added a silly little Hollywood kiss in the end. Ugh. I see why Moore didn't like the movie, but it's still enjoyable. It's just not a deep political statement, and not the place to go for one if our country is going to seriously address these issues. OK, rant over.

Two posts in two days and both of them disagreeing with you Dennis, I am becoming a nattering nabob of negativity as Spiro would say.

ReplyDeleteI hated this movie. I think I can take credit for initially directing your attention to it and the reason for my excitement was the extremely well written, densely layered novel. In contrast, found the movie to be trite, poorly made, obvious and a classic example of how Hollywood is incapable of really adapting anything in a meaningful way. The political message was so transparent (and I don't mean the Bush parallels which can be seen but are just a lens to use in viewing the movie) and the writers felt the need to explain everything to the audience. Some of the stuff you enjoyed (the addition of the gas attack by the government, is this a vieled 911 conspiracy theory?) didn’t have any real place in the story. What did it add? That subplot just goes away once the detective figures out it is V who is talking to him by the memorial. The romance was god awful and it seemed to only be there because there has to be a romance in a Hollywood movie. The supposedly horrible future had no horrible details, the scenes of people watching TV seemed more like examples of the lives of white middle class today than anything. Where is the grit that was all over the Matrix? The ending, not to spoil it for anyone, but it was unrealistic and it just seemed like an example of how to raise the stakes artificially rather than organically (why couldn‘t people show up to Parliament in their normal clothes? How does V afford/logistically work out/avoid detection while sending out several million packages?). The dialogue was stilted (I personally didn't like V's introduction, but I can see why someone would disagree), the acting was generally good (though Natalie Portman can not do much of a British accent) but on the whole the movie was just not very good.

I agree with you that the part about the lesbian was incredible, but that is because, unlike nearly everything else in the movie, they stuck to the novel. I keep meeting people who love this movie and my only solace in my bitterness after seeing what they did to Moore's brilliant work is a quote from the author himself: "Interviewer: ‘How do you feel about Hollywood ruining your work?’ Moore: ‘What are you talking about, they didn't ruin my work, it is right up there on the shelf.’"

(Guys, I apologize in advance for any egregious typos in these comments-- I'm typing on my wife's microscopically-sized laptop, and I feel like I have ten Italian sausages taped to my fingers...)

ReplyDelete"Where I disagree with some is in this desperate need to link the movie's political message to the (mis)deeds of the Bush administration. I have no problems making that case, but I just didn't see it in the film. The Wachowskis aren't masters of subtlety. If this is indeed an excorating repudiation of the Bush administration's actions in Iraq and Gitmo, etc., as I've read some critics in describing it, then it is stated poorly and amateurishly."

TLRHB: I think I’d agree with your assertion what McTeigue and the Wachowskis are up to is definitely not so much a systematic dismantling of the Bush administration per se. But they are making allusions to the current situation, and that’s fully what I expected. I’m not sure how you could make a film of V For Vendetta in 2005, or for that matter even read the original book, without making those connections on your own, and this is what I think the filmmakers are banking on us doing.

Some of the critics and bloggers you’re annoyed with are indeed projecting onto the film the kind of specific criticism of Bush/Blair, and that’s inevitable, not to mention easy. In some ways it’s like an alternative weekly’s dream op-ed movie. But the fact is, the film is first and foremost an entertainment, an engagement with a pre-existing creation in a new incarnation that presents a fairly common theme for futuristic films and literature– the repression and/or distraction of the masses by a totalitarian state– with an unusually troublesome figure– a terrorist– at its center and asks us to consider whether or not his methods are at all justified. Our knowledge of how the world has changed post-9/11 does not make exactly the sight of institutions like the Old Bailey and Parliament going up in fireballs any easier to process, no matter who we hold responsible for those changes. But however it has been retrofitted as a comment on the state of the world, I would agree with you that it’s misguidedly reductive to embrace V For Vendetta as the anti-Bush tract we’ve all been waiting for– wasn’t Fahrenheit 9/11 supposed to fill that bill, anyway?

I didn’t so much mind the Stephen Fry subplot, although by making Fry so similar in sensibility to V– right down to his collection of forbidden artifacts like the Koran hidden in his basement– they flirt pretty seriously with redundancy. I just found it jarring that we would be expected to believe a popular TV icon like himself would be so blind as to think that there wouldn’t be serious, violent, deadly fallout from his airing of that broad and bitter character assassination directed so openly at John Hurt’s government figurehead.

And your mentioning of the comic book being somewhat ambiguous about Evey’s fate at the end of the story reminds me of why I was left a litle unsatisfied as she and Stephen Rea’s detective stare out at the Parliament building going up in flames. I think I was sensing that element of ambiguity as missing without even realizing it.It puts m in mind of the conclusion of Zhang Yimou’s film Hero. The emperor sits triumphant in his palace, the battle won, yet he is clearly burdened an troubled, yoked with the terrible responsibility of knowledge that that victory has come at a terrible, repressive cost which will, as we in the audience know, ripple throughout China’s history. (This was somehow lost on those who denounced the film as a tacit endorsement of Chinese historical policy.)

Your mentioning of the ambiguity apparent in the conclusion of the comic book makes me even more anxious to continue reading it, because I realize there wasn’t enough of that going on in the movie. We’re left thinking mostly about V’s sacrifice, and there’s not much suggestion that all those citizens, in the Guy Fawkes outfits supplied by V, will do anything but band together as brothers to create the society we all know they’re capable of creating when left free of the forces of violent repression.

This, and that kiss, were the sops to Hollywood that V For Vendetta makes. Is it a sign of the quality of the movie, or my own distraction, tha in the end they didn’t matter that much to me as I looked at the big– and I mean Panavision-big– picture?

“The addition of the gas attack by the government... didn’t have any real place in the story. What did it add? That subplot just goes away once the detective figures out it is V who is talking to him by the memorial. The romance was god awful and it seemed to only be there because there has to be a romance in a Hollywood movie. The supposedly horrible future had no horrible details, the scenes of people watching TV seemed more like examples of the lives of white middle class today than anything...”

Benaiah: As I have to remind Blaaagh occasionally, what hppened to my edict about no disagreements with the blog host?! But seriously, folks, you are the one to blame for getting me interested in this film, that’s for sure. And though you may look on that as a bad thing, I certainly don’t. (It’s interesting, too, that our disagreements are about literary adaptations, each of us defending the literary work of Short Cuts and V For Vendetta over perceived botches in the adaptations to film.) I found the overarching literary-ness of the dialogue mostly charming in the way I think it was intended, and the rest of the dialogue, while not up to Shakespearean standards, certainly worked well enough to keep me riveted the entire way. I think the movie is pretty spectacular and successful on its own terms, those terms being a necessary reduction in the level of narrative density, and perhaps that evil ambiguity, that the comic book apparently has in spades. (I’m currently into the book and devouring it as rapidly as I can devour any reading material these days, although I bought the Barry Bonds books, Game of Shadows today, so I may yet again get distracted!)

As for your specific question about that genocidal virus conspiracy, it seems clear to me it was there to provide more background on this government’s activities and the lengths to which it will go to ensure the perpetuation of the dictatorship. As you said, investigation of that particular plot thread gets “dropped” once Rea realizes who the old man at the memorial really is because that’s why he’s investigating the genocide– to determine who V is. It necessarily takes a back seat at that point to the momentum of the narrative which has been building up to this point for nearly two hours, and off we go to Parliament.

But almost as importantly, for me anyway, it allows for the introduction of the doctor played by Sinead Cusack, who participated in the viral experimentation at Larkhill without really understanding its true implications until it was too late. Her assassination at the hands of V is one of the movie’s most sublime moments. As David Edelstein said in his review of V, “There’s a haunting dissonance when he comes for an already guilt-ridden physician. A three-dimensional vigilante picture needs (at least) one non-triumphant execution to gum up the machine.”

As for the “romance,” I think it might be overstating a little to describe the relationship between V and Evey thusly, although you’re absolutely right that the kiss is a bit much. Finally, I didn’t miss the futuristic “grit” that was so prevalent in th Matrix sequels– I'd prefer the rather generic depictions of the TV-watching citizenry if it meant I could be spared another overwrought depiction of a multicultural pluralistic society like the one in that second Matrix film where the Wachowskis gave up all that screen time to that big orgiastic mosh pit scene. Besides, isn’t the fact that “the scenes of people watching TV seemed more like examples of the lives of white middle class today than anything...” at least partially the point?

I did love your Alan Moore quote, and it made me think of him as a little less bitter and vituperative and perverse a character when it comes to the subject of adaptations of his books. I’m going to take his advice and head back to the book. Then maybe it’ll be time to revisit the film of V For Vendetta once again. For now, it remains for me a terrific movie, one that I won’t mind revisiting, whether I change my perspective on it or not.

Thanks, David. I look forward to your review. Your response upon a second viewing intrigues me, and I've been wrestling with trying to figure out when I can take the opportunity to see it again, just so I can see what happens to my own perceptions. The movie seems to be demanding that of me, and I take your comments as confirmation of it. I'll keep my eye out for your piece!

ReplyDeleteDennis, going off topic here, but I finally watched BUFFALO BILL AND THE INDIANS tonight. What a masterpiece. It's funnier than MASH! I loved it, and thought it made some damn good points about the hucksterism and commercial underpinning of America and the way we create false history in between some great scenes of sheer hilarity. Anyway, I hope you get around one day to writing a piece on it, I'd love to read it.

ReplyDeleteTLRHB: Me too! I love that movie more and more each time I see it. I don't remember if you said whether you'd seen Secret Honor or not, and it could just be that both films were based (in the case of BB very loosely, and with SH very strictly) on plays, but there were some striking similarities between the two films and the way they approached their protagonists. The scene where Bill Cody wakes up at night and monologues in the "presence" of Sitting Bull struck me as tonally, visually and thematically very similar to Secret Honor. A comparison of the two might be really worthwhile. But back to Buffalo Bill, I really hope to get to that article I originally intended to write, and sometime soon. It is a great movie, and it really cracks me up to even think that because, just like Nashville, I hated it so much when I first saw it, at age 16. And just like Nashville, I've had to age into it. But this last time watching it, I was struck by how much I was enjoying just soaking in the milieu that Altman creates--that whole world of the Wild West show is just so vivid and funny.

ReplyDeleteI'm a latecomer to this discussion--in case anyone is still reading it!--but I finally saw V FOR VENDETTA yesterday (on an IMAX screen, even!) and I'm in almost total agreement with what you wrote here, Dennis. I did like the Benny Hill-type TV segment a lot, though, and it didn't bother me that the Stephen Fry character mirrored the character of V. I also think a bit more of Natalie Portman as an actress...I thought she did good work in both GARDEN STATE and CLOSER, and yeah, though her British accent could use some work, she did some really good work in V as well. If a lot of people seem disappointed in the movie because they think it doesn't do justice to the book, I guess I ought to get my hands on that--I thought the movie was terrific.

ReplyDeleteBlaaagh-- Glad to see you chime in here. I got some comments in an e-mail which I will post when I get back to the office (I'm working at home today) which shed a lot of light on that Stephen Fry character and the motivation behind that TV show that I found so troubling. Look for them tomorrow, plus a link to David Lowery's article that he alluded to in one of the comments above. Oh, and I'm really glad you liked the movie too.

ReplyDelete