UPDATED 3/15/06 9:38 am

UPDATED 3/15/06 9:38 am NOTE: This is the final installment of my personal retrospective on the films of Robert Altman, in honor of the director's 81st birthday and the honorary Oscar bestowed upon him by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences during last Sunday's Oscar ceremonies. You can access part one of this article by scrolling down this page or by clicking here. Part two of this article can also be found by scrolling down the page or by clicking here. Part three can be found by scrolling down or clicking here.

*********************************************************************************

By the time the ‘80s were lurching to a close, it might not have been unreasonable for fans and appreciators of Robert Altman’s films to think that he might be at a sort of crossroads. He’d spent nearly the entire Reagan era doing theater and adapting plays into films, all of them on a scale that allowed him complete artistic freedom and control, but that also kept his work almost on the level of a connoisseur’s well-kept secret—not exactly, except in certain circles, what you’d call high profile projects. Would he continue on in this mode, shrugging that Altmanesque shrug, perhaps only to dribble away into irrelevancy? Or would he look down other paths until he found the right road on which to travel and ensure that his art would remain vital? How fitting, in a specifically ironic-twist kind of way, that the projects which would ultimately pave the way for Altman’s re-emergence into a larger cinematic consciousness, and into the kind of acceptance within Hollywood that he hadn’t experienced since the heyday of the early to mid ‘70s, would be television projects. It wouldn’t exactly be a return-to-his-roots kind of television either, but a furthering of his artistic concerns with the medium in narrative formats that would seem familiar to those who followed his work in the dark shadows of the ‘80s, and also to those who remembered the heights he scaled with The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs. Miller and California Split and Nashville. By infusing a well-made play with new blood (and timeliness), and by tackling the American political process and causing us to re-examine our own participation in it (in an election year, no less), Altman would, to everyone who was not paying attention in the years immediately following the Popeye-inspired exile, seem to make a spectacular comeback. To everyone who was paying attention, it would seem instead that a sleeping audience was finally beginning to wake up.

By the time the ‘80s were lurching to a close, it might not have been unreasonable for fans and appreciators of Robert Altman’s films to think that he might be at a sort of crossroads. He’d spent nearly the entire Reagan era doing theater and adapting plays into films, all of them on a scale that allowed him complete artistic freedom and control, but that also kept his work almost on the level of a connoisseur’s well-kept secret—not exactly, except in certain circles, what you’d call high profile projects. Would he continue on in this mode, shrugging that Altmanesque shrug, perhaps only to dribble away into irrelevancy? Or would he look down other paths until he found the right road on which to travel and ensure that his art would remain vital? How fitting, in a specifically ironic-twist kind of way, that the projects which would ultimately pave the way for Altman’s re-emergence into a larger cinematic consciousness, and into the kind of acceptance within Hollywood that he hadn’t experienced since the heyday of the early to mid ‘70s, would be television projects. It wouldn’t exactly be a return-to-his-roots kind of television either, but a furthering of his artistic concerns with the medium in narrative formats that would seem familiar to those who followed his work in the dark shadows of the ‘80s, and also to those who remembered the heights he scaled with The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs. Miller and California Split and Nashville. By infusing a well-made play with new blood (and timeliness), and by tackling the American political process and causing us to re-examine our own participation in it (in an election year, no less), Altman would, to everyone who was not paying attention in the years immediately following the Popeye-inspired exile, seem to make a spectacular comeback. To everyone who was paying attention, it would seem instead that a sleeping audience was finally beginning to wake up. THE CAINE MUTINY COURT-MARTIAL (1988) It was hard to believe, when I read the TV listings for that Sunday night back in 1988, that there was a new Robert Altman movie on the way, and it was playing on CBS. But there it was, and there was no way I could possibly miss it. I remember being thrilled to see the military procession, filmed through Altman’s zooming, probing lens that opens the movie in such a muted fashion. (Hearing the marches played by a brass band, here imbued with an unsettling, mournful quality, sounded a lot like how the brass band score overlaid on the football game in M*A*S*H would sound if were being played at a funeral.) Altman’s uncut adaptation of Herman Wouk’s play gets underway slowly, deliberately, and the players—Jeff Daniels, Eric Bogosian, Michael Murphy, Daniel Jenkins, Kevin O’Connor—lay the table with much pleasure for probably the best TV movie of the decade. (Admittedly, the competition was slight—we were used to thinking of TV movies in terms of Meredith Baxter Birney getting hooked on smack, or Tori Spelling sleepwalking through lurid titles like Mother, May I Sleep With Danger? Few TV movies could approach the quality of craft and the artistic intelligence of Altman’s film, and the form itself would start to die off for the big three networks in the early ‘90s, only to emerge revitalized on HBO and Showtime.) But I was thrown for a while, the first time I saw Caine Mutiny Court-martial, by the excessive stylization of Brad Davis’ performance as Captain Queeg. He seemed to stick out like a very sore thumb amongst the seasoned players that were otherwise working in Altman’s milieu and merging seamlessly with the pictorially probing yet unassuming style of the film. Davis, on the other hand, seemed excessively paranoid and jangled, all tics and beats pounding rhythmically between his ears to a manic tune no one else seemed to be hearing. I left the movie feeling that his Queeg was the fly in the ointment, that the actor seemed overwhelmed by his assignment, intimidated by his director, and outclassed by his cast mates. But of course I was missing the point. It was only upon turning the movie over in my head in the days and weeks that followed that Altman’s plan began to click for me. (That it took so long, taking a backseat to my sense of enjoyment of it as drama is, I think, not necessarily a bad thing.) I began to realize, in contemplating it afterward, how Altman was channeling the events of the day to inform his film-- Oliver North and the Iran-Contra hearings must have been foremost on his mind. Indeed, much of the trial is staged to suggest camera placement familiar from those hearings, and North’s own twisted and impenetrable sense of morality is most definitely (and purposefully) echoed in Davis’ characterization, which itself seems, in light of comparison to North, purposefully and satirically overscaled, not a miscalculation at all. (And, after all, what is Humphrey Bogart’s Queeg if not grand and grotesque, bug-eyed and over-the-top?) I’ve seen The Caine Mutiny Court-martial a couple of times since it’s initial showing (it was released on VHS and laserdisc in 1992) and it has remained an exciting and powerful work in my memory, and it joins many of the other Altman films I’ve talked about in this series that I’m eager to revisit.

THE CAINE MUTINY COURT-MARTIAL (1988) It was hard to believe, when I read the TV listings for that Sunday night back in 1988, that there was a new Robert Altman movie on the way, and it was playing on CBS. But there it was, and there was no way I could possibly miss it. I remember being thrilled to see the military procession, filmed through Altman’s zooming, probing lens that opens the movie in such a muted fashion. (Hearing the marches played by a brass band, here imbued with an unsettling, mournful quality, sounded a lot like how the brass band score overlaid on the football game in M*A*S*H would sound if were being played at a funeral.) Altman’s uncut adaptation of Herman Wouk’s play gets underway slowly, deliberately, and the players—Jeff Daniels, Eric Bogosian, Michael Murphy, Daniel Jenkins, Kevin O’Connor—lay the table with much pleasure for probably the best TV movie of the decade. (Admittedly, the competition was slight—we were used to thinking of TV movies in terms of Meredith Baxter Birney getting hooked on smack, or Tori Spelling sleepwalking through lurid titles like Mother, May I Sleep With Danger? Few TV movies could approach the quality of craft and the artistic intelligence of Altman’s film, and the form itself would start to die off for the big three networks in the early ‘90s, only to emerge revitalized on HBO and Showtime.) But I was thrown for a while, the first time I saw Caine Mutiny Court-martial, by the excessive stylization of Brad Davis’ performance as Captain Queeg. He seemed to stick out like a very sore thumb amongst the seasoned players that were otherwise working in Altman’s milieu and merging seamlessly with the pictorially probing yet unassuming style of the film. Davis, on the other hand, seemed excessively paranoid and jangled, all tics and beats pounding rhythmically between his ears to a manic tune no one else seemed to be hearing. I left the movie feeling that his Queeg was the fly in the ointment, that the actor seemed overwhelmed by his assignment, intimidated by his director, and outclassed by his cast mates. But of course I was missing the point. It was only upon turning the movie over in my head in the days and weeks that followed that Altman’s plan began to click for me. (That it took so long, taking a backseat to my sense of enjoyment of it as drama is, I think, not necessarily a bad thing.) I began to realize, in contemplating it afterward, how Altman was channeling the events of the day to inform his film-- Oliver North and the Iran-Contra hearings must have been foremost on his mind. Indeed, much of the trial is staged to suggest camera placement familiar from those hearings, and North’s own twisted and impenetrable sense of morality is most definitely (and purposefully) echoed in Davis’ characterization, which itself seems, in light of comparison to North, purposefully and satirically overscaled, not a miscalculation at all. (And, after all, what is Humphrey Bogart’s Queeg if not grand and grotesque, bug-eyed and over-the-top?) I’ve seen The Caine Mutiny Court-martial a couple of times since it’s initial showing (it was released on VHS and laserdisc in 1992) and it has remained an exciting and powerful work in my memory, and it joins many of the other Altman films I’ve talked about in this series that I’m eager to revisit.

TANNER ‘88 (1988)

“Exercise your right to vote

Choose the one you like the most

It's your individual right to choose

The one you want to fight for you

Vote!

Pick the proper candidate

You can change the course of fate

It's a decision you must make to choose

The one you think is great for you

Vote!”

That campaign song recurs throughout all 11 episodes of Tanner ‘88, trumping even John Williams’ “The Long Goodbye” for ubiquity (if not flexibility of form) over the course of a single Altman project. The director, collaborating this time not only with his usual company of superb actors (and a collection of real-life politicos who were actually out on the campaign trail while Tanner mixed it up with them in pursuing his fictional presidential candidacy), but with the most high-profile screenwriter of his career, Garry Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury. (I’m not counting Sam Shepard here, or any of the other playwrights like Wouk or Rabe that Altman adapted in the ‘80s, because the texts in those instances remained essentially the same or, in Wouk’s case, restored to its original form—they weren’t true collaborations in the way Altman has trained us to think of a collaboration.) Tanner’s campaign song, in concert with his curt slogan—“For Real”-- accesses a kind of Walkerian (as in Hal Phillip) simplicity and naivete that runs in bracing contrast to the spectacular surgical precision (amidst all the usual glorious Altmanesque clutter and loquacity) with which Altman and Trudeau dismantle, satirize, mock, soberly examine and criticize the mainstreaming of media influence and marketing into the political process circa 1988. No surprise—seeing it in 2006 in no way diminishes the trenchant points the two were making; if anything, it emphasizes how much more of a mean-spirited circus the process has become in the intervening years. Pat Robertson and Bob Dole and Ralph Nader were one thing; it’s much harder to imagine Tanner encountering Bush and Cheney on the campaign trail and having them good-naturedly participate as if they were encountering a familiar political rival in front of Altman’s cameras—though it’s fun to imagine the sky-high entertainment value the inevitable plethora of outtakes would generate as W struggles to improvise believably with Michael Murphy et al.)

My one regret about last weekend’s Altman Blog-a-Thon (to which this fourth installment in my retrospective is surely the last piece to be submitted) is that no one took on the task of dissecting and considering Tanner ‘88*, a task that is certainly more than I’m up to at the moment, either intellectually or in terms of the time I’d have to offer such an undertaking. Tanner '88 remains for me a work that consistently rewards, as does all the best of Altman, repeated and close viewing, for the extrication of its brilliant lines of thinking on the various social and political issues it weaves into its scenarios, and for all the amazing instances of throwaway behavior that the camera catches on the fly. It may be Altman’s most densely packed work, and that’s really saying something. The series' under-the-coffee-table view of the process of primary elections, intimate and surreptitious and revealing of that system’s ultimate exclusivity, resonates like few other works of art that have taken the hungry beast of the American political process as its subject. (I have not yet caught up with Altman and Trudeau's follow-up, entitled Tanner on Tanner, but it's definitely on my Netflix queue.

Note too that the Criterion disc of Tanner '88 features all new bumpers before each episode, "interviews" with Michael Murphy, Cynthia Nixon and Pamela Reed, in character, reminiscing about the '88 campaign. Those bumpers are excellent bits in themselves and well worth a look.)

Note too that the Criterion disc of Tanner '88 features all new bumpers before each episode, "interviews" with Michael Murphy, Cynthia Nixon and Pamela Reed, in character, reminiscing about the '88 campaign. Those bumpers are excellent bits in themselves and well worth a look.)* I never mind being proven wrong, especially when it leads to more good writing. Seems I was errant in my claim that no one wrote about Tanner '88 for the Altman Blog-a-Thon. In fact, Quiet Bubble submitted an excellent essay, which I read with pleasure this morning, that more than fulfills my desire to have a good writer wrap his or her head around Altman's teeming and provocative miniseries. Thanks, QB!

VINCENT AND THEO (1990) I saw Vincent and Theo with my wife when we were first getting to know each other, before we would even consider our outings to movies and restaurants and the like as “dates.” She was professedly unimpressed with Altman as a director—I remember a particularly heated discussion about Nashville in a Denny’s off the 405 in Irvine from which I emerged thinking, “Well, if that doesn’t derail this budding relationship, nothing will.” (A premise that was adequately proven when I later revealed my affinity for the films of Brian De Palma.) I remember her expressing anger and frustration at Altman as the lights came up on Vincent and Theo over the director’s mistreatment, as she perceived it, of the character played by Johanna ter Steege. She felt this mistreatment was indicative of Altman’s general disregard for women, and this negative response was one she had to the entire film. I remember being a little confused by that objection, as the character didn’t seem to me to have been excessively abused or humiliated by the director. I remember finding the movie much more interesting than my soon-to-be-wife did, particularly as an acting exercise, but frustrating in the way that many films about artists, particular painters and writers, are—it’s exceedingly difficult to dramatize the creative process and demonstrate why a man like van Gogh, apart from his looming reputation and the excessive prices for which his paintings have been auctioned, was a great artist (the contribution made by Martin Scorsese and Richard Price to the New York Stories omnibus, Life Lessons, seems to cut much closer to this particular bone). I can remember watching Vincent and Theo and thinking of the myriad ways in which I recognized it as a work worthy of respect amidst the whole of Altman’s filmography, but it has never resonated with me like many of his films have and I have never felt particularly compelled, in the ensuing 16 years since its release, to re-experience it. I have a feeling I shall soon, but for now it remains a minor Altman film for me.

VINCENT AND THEO (1990) I saw Vincent and Theo with my wife when we were first getting to know each other, before we would even consider our outings to movies and restaurants and the like as “dates.” She was professedly unimpressed with Altman as a director—I remember a particularly heated discussion about Nashville in a Denny’s off the 405 in Irvine from which I emerged thinking, “Well, if that doesn’t derail this budding relationship, nothing will.” (A premise that was adequately proven when I later revealed my affinity for the films of Brian De Palma.) I remember her expressing anger and frustration at Altman as the lights came up on Vincent and Theo over the director’s mistreatment, as she perceived it, of the character played by Johanna ter Steege. She felt this mistreatment was indicative of Altman’s general disregard for women, and this negative response was one she had to the entire film. I remember being a little confused by that objection, as the character didn’t seem to me to have been excessively abused or humiliated by the director. I remember finding the movie much more interesting than my soon-to-be-wife did, particularly as an acting exercise, but frustrating in the way that many films about artists, particular painters and writers, are—it’s exceedingly difficult to dramatize the creative process and demonstrate why a man like van Gogh, apart from his looming reputation and the excessive prices for which his paintings have been auctioned, was a great artist (the contribution made by Martin Scorsese and Richard Price to the New York Stories omnibus, Life Lessons, seems to cut much closer to this particular bone). I can remember watching Vincent and Theo and thinking of the myriad ways in which I recognized it as a work worthy of respect amidst the whole of Altman’s filmography, but it has never resonated with me like many of his films have and I have never felt particularly compelled, in the ensuing 16 years since its release, to re-experience it. I have a feeling I shall soon, but for now it remains a minor Altman film for me.Fortunately, Peter Nellhaus chose the film for his contribution to the Altman Blog-a-Thon, and his brief piece provides a clear perspective which may be fairly representative of the thoughts, however organized or unformed, of many of the film’s detractors. Here’s Peter:

“If one has limited knowledge about art and artists, Vincent and Theo reinforces the idea that the film was made simply because the artist was famous, leaving why he is famous unanswered. By presenting van Gogh as the proto tortured and starving artist while ignoring the meaning of his artwork, Vincent and Theo becomes a film about a person who is famous for being famous, a celebrity biography with claims to higher aspirations.”

(In between Vincent and Theo and Short Cuts, Altman directed an opera based on Frank Norris’ novel McTeague, which also served as the inspiration for Erich von Stroheim’s notoriously butchered silent film Greed, and a performance film featuring Ruth Brown, Bunny Briggs, Linda Hopkins and a host of others entitled Black and Blue. I used to have a copy of Black and Blue on VHS, but somehow it no longer exists, and I have never seen McTeague. If anyone has any tips on how I can hook up with these titles, I’d very much appreciate the guidance.)

THE PLAYER (1992) The way all of Hollywood lined up to be in Altman’s adaptation of Michael Tolkin’s blistering novella about Hollywood’s dark underbelly, and the way the town was buzzing about how big an event the finished film would certainly become, told a lot, in the days before the movie’s release, about the movie industry’s amusing insularity (partially the subject of the film), and it also revealed to a startling degree just how much they really didn’t seem to “get it.” It also said a lot about the acting community in particular and their genuine respect for the director that they would be so willing to prostrate themselves and clamor so publicly just to be a small part of Altman’s big inside joke. If I was an actor, I bet I’d worship Altman too, given his track record with performances and his willingness to suggest that three-quarters of what’s good about any of his movies is the result of what the actors bring to the process. It’s a very generous assessment that I don’t doubt Altman on some level believes, even though I’ve often thought it sounded a little bit disingenuous. The sense of glee he takes at shredding Hollywood, his old nemesis, from the inside out, and the level of craft that he displays in The Player’s opening shot alone, proves that it’s not just the actors providing the juice here. That famous tracking shot serves as a parody of Welles, a pat on the back for the more self-congratulatory film buffs in the audience, sure, but more importantly it establishes itself as a brilliant distillation of the workings of a studio and an astringent look at the desperation involved in hatching a saleable idea-- the camera creeps past bungalow windows, allowing us to eavesdrop on some pretty farfetched pitches, some of which sound just plausible enough that I bet more than one studio exec, missing the point for surely not the last time during the film’s very entertaining two hours, probably thought, “Hey, why didn’t I think of that?” upon first encountering the film.

THE PLAYER (1992) The way all of Hollywood lined up to be in Altman’s adaptation of Michael Tolkin’s blistering novella about Hollywood’s dark underbelly, and the way the town was buzzing about how big an event the finished film would certainly become, told a lot, in the days before the movie’s release, about the movie industry’s amusing insularity (partially the subject of the film), and it also revealed to a startling degree just how much they really didn’t seem to “get it.” It also said a lot about the acting community in particular and their genuine respect for the director that they would be so willing to prostrate themselves and clamor so publicly just to be a small part of Altman’s big inside joke. If I was an actor, I bet I’d worship Altman too, given his track record with performances and his willingness to suggest that three-quarters of what’s good about any of his movies is the result of what the actors bring to the process. It’s a very generous assessment that I don’t doubt Altman on some level believes, even though I’ve often thought it sounded a little bit disingenuous. The sense of glee he takes at shredding Hollywood, his old nemesis, from the inside out, and the level of craft that he displays in The Player’s opening shot alone, proves that it’s not just the actors providing the juice here. That famous tracking shot serves as a parody of Welles, a pat on the back for the more self-congratulatory film buffs in the audience, sure, but more importantly it establishes itself as a brilliant distillation of the workings of a studio and an astringent look at the desperation involved in hatching a saleable idea-- the camera creeps past bungalow windows, allowing us to eavesdrop on some pretty farfetched pitches, some of which sound just plausible enough that I bet more than one studio exec, missing the point for surely not the last time during the film’s very entertaining two hours, probably thought, “Hey, why didn’t I think of that?” upon first encountering the film. There’s a lot to enjoy in this rather fizzy (for an Altman film) comedy, and it’s not surprising that most of the ire Altman works out is directed toward those greasy studio types that he constantly baited, and who so eagerly took the bait, as he first began navigating the tributaries of Hollywood in the ‘70s. And it’s ultimately a pretty grim affair, what with murderous studio head Griffin Mill’s triumphant assimilation into the life of the screenwriter he killed, stroking the pregnant belly of the screenwriter’s ex-girlfriend, heading off, as the film ends, to a scot-free life of privilege decorated by the picket-fence Americana of a thousand small-town movie fantasies that have been grafted rather neatly onto his own corrupt Hollywood lifestyle. I just wish the movie as a whole had the sense of consequence that Altman successfully conveys in his conclusion.

There’s a lot to enjoy in this rather fizzy (for an Altman film) comedy, and it’s not surprising that most of the ire Altman works out is directed toward those greasy studio types that he constantly baited, and who so eagerly took the bait, as he first began navigating the tributaries of Hollywood in the ‘70s. And it’s ultimately a pretty grim affair, what with murderous studio head Griffin Mill’s triumphant assimilation into the life of the screenwriter he killed, stroking the pregnant belly of the screenwriter’s ex-girlfriend, heading off, as the film ends, to a scot-free life of privilege decorated by the picket-fence Americana of a thousand small-town movie fantasies that have been grafted rather neatly onto his own corrupt Hollywood lifestyle. I just wish the movie as a whole had the sense of consequence that Altman successfully conveys in his conclusion. He’s having fun with his actors, and the movie is undeniable fun, but I just wish it had more of the true, profound sting throughout that we’re left with as the movie ends. Seeing The Player on opening weekend in the heart of Hollywood, surrounded by an auditorium packed with celebrities and industry types, was a strange and disconcerting experience. It was a bitterly funny movie, and not incidentally a fairly nasty one, that was being received by this particular audience—in reality, the film’s target-- as an insider love letter to the movie business. Each tiny throwaway line and gesture was greeted with howls of knowing laughter—it almost felt like a game of one-upsmanship to see who could be seen and heard laughing and responding to every perceptible reference the movie had to offer. It was easy to imagine the movie not going down with such approving applause and incessant, almost boorish laughter in, say, Peoria.

He’s having fun with his actors, and the movie is undeniable fun, but I just wish it had more of the true, profound sting throughout that we’re left with as the movie ends. Seeing The Player on opening weekend in the heart of Hollywood, surrounded by an auditorium packed with celebrities and industry types, was a strange and disconcerting experience. It was a bitterly funny movie, and not incidentally a fairly nasty one, that was being received by this particular audience—in reality, the film’s target-- as an insider love letter to the movie business. Each tiny throwaway line and gesture was greeted with howls of knowing laughter—it almost felt like a game of one-upsmanship to see who could be seen and heard laughing and responding to every perceptible reference the movie had to offer. It was easy to imagine the movie not going down with such approving applause and incessant, almost boorish laughter in, say, Peoria. Another participant in the Altman Blog-a-Thon, the Self-Styled Siren, delivered a terrific post on The Player last weekend, entitled ”Robert Altman Says It To Their Faces”. The SSS provides yet another sharp and funny perspective, as is her typical mode, on the movie that brought Altman, however briefly, back onto the A-list. I gratefully acknowledge her smart observations about the picture and hope you’ll enjoy reading her post as much as I did.

SHORT CUTS (1993) And now for a bit of blasphemy... Short Cuts is a movie that many, in the afterglow of The Player, were quick to proclaim another masterpiece on the level of Nashville, and believe me, when I went to see it the day it opened, that was just what I was hoping I’d see, just what I’d convinced myself ahead of time that I inevitably would see. And for days and weeks and months afterward I kept trying to reconcile all those glowing notices with the nagging disappointment and disillusionment I felt over the film. The truth was, as I would come to acknowledge in a process that spanned approximately the last 10 years, I didn’t like Short Cuts much at all. In fact, when I sat down with it to create the subtitles for the recently released Criterion DVD edition, I came away with the realization that not only did I not like it, I pretty much hated it. For me, Short Cuts, the movie that many revere and place amongst the highest achievements in the Altman canon, is a bitter, lazy, ugly and fruitless exercise in cultural condescension and narrative dead-ends that take the form of Altman’s most successful experiments in overlapping storytelling and allusive connections, but are as wilted on the vine as those other great works are still vibrant and alive and continuing to flower with each new viewing.

It was asked recently in the comments section of Matt Zoller Seitz’s blog The House Next Door whether or not there was anyone who believed the frequent charges of misanthropy in regards to Altman’s films had any merit. I generally find the "misanthrope" tag not applicable in any meaningful way to Altman's approach—his oft-observed fraternity with his actors and his willingness to express admiration and love for even the most lowly and screwed-up of his characters seems to preclude such conclusions. But even if Altman was a raging misanthrope, that wouldn't negate him or diminish him for me as an artist if he had something interesting to say to go along with that attitude, and amplified it with his usual stylistic command.

It was asked recently in the comments section of Matt Zoller Seitz’s blog The House Next Door whether or not there was anyone who believed the frequent charges of misanthropy in regards to Altman’s films had any merit. I generally find the "misanthrope" tag not applicable in any meaningful way to Altman's approach—his oft-observed fraternity with his actors and his willingness to express admiration and love for even the most lowly and screwed-up of his characters seems to preclude such conclusions. But even if Altman was a raging misanthrope, that wouldn't negate him or diminish him for me as an artist if he had something interesting to say to go along with that attitude, and amplified it with his usual stylistic command. That said, I find Altman's attitude in Short Cuts toward the people he portrays, and the city he supposedly investigates, as veering dangerously close to poisonous. Any mosaic of human behavior that finds so little room for anything other than the suffocating relationships and subodinated rage (all the better for lifting the roofs off the houses in suburban Los Angeles, as the director has suggested, and exposing the way people outside the moneyed neighborhoods really live) betrays, I think, a somewhat puny and vinegary vision of humanity. And for a movie that claims such lofty intent as to get at an examination of the “real” Los Angeles—that is, outlying neighborhoods like Downey and Glendale and Santa Ana, et al.—the movie is startlingly homogenous and narrow-minded in its observations, and it doesn’t feel any more like the Los Angeles I’ve known for almost 20 years than does Sunset Boulevard or Die Hard or Lost Highway or 1941—in fact, it feels a whole lot less like Los Angeles to me than any of those films do. (Thom Andersen, in his film Los Angeles Plays Itself, expressed a similar distrust and annoyance with Short Cuts and Altman for presuming to construct a narrative about the city’s middle classes when the end result feels as if he’s never left Beverly Hills. For a film allegedly about Los Angeles, Short Cuts skews awfully white.) That’s all the more distressing when you think of the heights Altman’s earlier films have scaled when it comes to presenting a range of emotion and human behavior, explicable and eccentric, none of which ever seemed to come bearing labels or preconceptions, and none of which ever seemed so narrowly intended to represent, in such a general way, the bitter existence of a specific group of people (I think even the mean-spiritedness of A Wedding comes off looking more evenhanded that does the meandering brutality of Short Cuts.)

And just as a piece of entertainment I found Short Cuts, upon my most recent viewing last year, to be largely annoying-- there's an awful lot of scenes involving actors yelling presumably cutting things at each other that seem atypically unshaped and left to dangle within the Nashville-like interlocking story structure. In this regard, I find the Tim Robbins-Madeline Stowe and the Frances McDormand-Peter Gallagher storylines ridiculously miscalculated-- this is the quintessence, I think, of black humor that doesn't work at all allowed to dribble on and on and make the same dubious points over and over again about the myopia and hatefulness of the characters. Much is frequently made of the story involving Matthew Modine and Julianne Moore, particularly in regard to her nudity. But it is hardly ever observed just how shrill and unmoored their performances seem in this scene, even accounting for Moore’s unblinkered exposure of her natural redheadness. Modine, in particular, seems out of his league and does little more than yell helplessly. By the time this couple gets together with Anne Archer and Fred Ward (whose own potentially volatile storyline, involving the discovery of a corpse, reaches the same dead end), and they all get drunk and start putting on clown makeup and making faces at each other, the movie has deteriorated into an imitation of convoluted behavior that seemed ill-advised when Antonioni tried it in Blow-up 20 years earlier. The one story that does attempt to grab at our emotions-- the baker tormenting the family whose son has died after being hit by a car-- is fatally undermined by some of the worst performances I’ve ever seen in an Altman film, courtesy of Andie McDowell, Lyle Lovett, Jack Lemmon. (Only Bruce Davison, as the boy’s father, and Lily Tomlin, as the waitress who hits the child and halfheartedly attempts to help him, come off well here. And don’t get me started on Tom Waits, as Tomlin’s parasitical boyfriend, who is far less charming than Altman, and eventually Tomlin, seems to think he is.)

I don't usually like to play the literature card as a finger-wagging comparison when thinking about adaptations either, but the way Raymond Carver (whose stories are the ones being pilloried here for their artistic cachet) develops this same situation, with such poetry and simplicity and understated agony, shames Altman's rendering of it. One of the major problems I have with Short Cuts is the degree to which it relies on Carver’s reputation to paper over the deficiencies in the film on a conceptual level, on a performance level, and on a directorial level. The estate of Raymond Carver, in the personage of Carver’s lover and fellow poet Tess Gallagher, gave Altman carte blanche here and was (and continues to be, if the DVD is any indication) completely suportive of the undertaking to marry Carver’s sensibility with that of Altman. In watching the bonus material on the DVD, it’s somewhat discomfiting to see how Gallagher and the usual gallery of talking actor heads are so eager to go on and on about how the two artists' sensibilities meshed so well on the project; I think that the very opposite is true.

Carver's sense of locale, of often kind, often ruthless introspection, of precise but never too-clever poetry, is constantly at odds with Altman's amorphous melting-pot sensibility (at least as it is articulated here). And it's a fatal miscalculation to just assume that Carver's stories, so rooted in the rhythms and observations of the Northwest, could simply be transplanted to Los Angeles with so little in the way of a leap of creative reimagination. It's almost like saying that what's really important about Carver was not his literary voice, his longing to connect in abstract and very real ways with his environment, the stillness of his approach, and the way the man put words together, but instead his plots. Altman wants to score easy points off the boorish behavior and closed-off experience of a group of characters for whom he has little of his characteristic warmth and acceptance of their various oddities and blemishes, but instead plenty of uncharacteristic contempt. And he wants to get away with it by taking on the mantle of a fellow artist whose particular vision was full of harshness and bitter truth, but also open to the possibility of the kind of transcendence that is shrugged off and pooh-poohed here in favor of a curdled hopelessness. That's what Short Cuts boils down to for me—the appropriation of superior material put to the service of a narrow and calculatedly ugly portrait of humanity. The fact that it is easily Altman's most unpleasant movie on a surface and a subterranean level makes it one that I hope never to have to see again.

PRET-A-PORTER (Ready To Wear) (1994)

On the other hand, I love the crazy-quilt, ridiculous party pitch of Pret-a-Porter, even the poop jokes (I loved 'em in Brewster McCloud too.) Brian Darr, in a discussion of the film over at The House Next Door, made an observation that I hadn't considered about the film’s fascination with dog shit that I really like, and that is its function as a sophomoric reminder that even beautiful Paris is subject to the whims of nature, and that there might just be a smell that travels along with those whims that could go a step or two toward explaining the city's pungent quality. (Now, there's an element that might transfer to Los Angeles, or any other city, with much more reasonable efficiency than using Raymond Carver as a skeleton for a series of bitter, seriocomic stylistic riffs and calling it a meeting of artistic minds.)

I'm in love with the cacophony of Altman's films in general, Pret-a-Porter being the most "what-the-fuck" of all of his big party films, and I enjoy the fact that it seems so haphazardly smashed and crumpled and taped together. Particularly after the sour mash of Short Cuts, I found the fizziness of Pret-a-Porter, and its disregard for looking foolish or inconsequential, or even coherent, to be a welcome tonic. And any movie that allows Marcello Mastroianni and, more importantly, Sophia Loren to revisit that striptease from Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (this time with a twist) has nothing to be ashamed of in my book, regardless of whether it all "works" or not. I'm glad it's out there. Pret-a-Porter is probably my favorite Altman orphan.

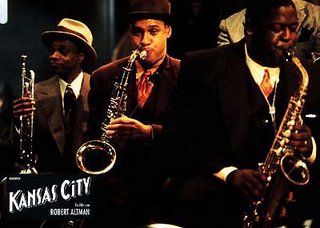

KANSAS CITY and JAZZ ‘34 (1996)

Altman’s love letter to his home city is, in a lot of ways, a great movie—it’s atmospheric, the jazz milieu is brilliantly imagined and staged, and the way the music interweaves with the story lends it the kind of swaying, syncopated texture that keeps you constantly in its grasp, even when you sense the narrative and the actors failing the director. (George Clooney employed the same kind of visual/aural snytax in punctuating his Good Night, and Good Luck with all those smoky, insinuating numbers teased and belted out by Diane Reeves.) But Kansas City is simply less compelling as a piece of storytelling, even as it deconstructs the attendant mythology surrounding the 100-proof gangster milieu in which the film is soaked and examines the way race and politics were inextricably intertwined in the city in the 1930s. It has at its center a terrifying and nuanced perfomance by Harry Belafonte as the seductive gangster Seldom Seen, and two very odd, overmodulated performances by Jennifer Jason Leigh, who resorts to kindapping the wife of a local politican (Miranda Richardson, dulled by a drug habit and still threatening to spin wildly right out of the movie) in order to secure through blackmail the release of her husband, a petty thief being held under Seldom Seen’s thumb. The film left a unsatisfying aftertaste when I last saw it, even as its atmosphere provides so much to enjoy and in which to become lost in reverie. But strangely enough, as I write about it now I feel the film pulling at me, beckoning me to get lost in it again, to re-evaluate it and search within it and follow the trails left by its various characters as they make their way through the film’s smoky moral morass. Even though I saw it only six months ago, I already feel like going back to Kansas City, which could be no better indication that I might have missed something the last couple of times I passed through. It’s Altman, after all, so I know I’ll return. And when I do, I’d love to see it alongside Altman’s wonderful documentary Jazz ‘34, which gives over full-time to the jazz musicians who were only intermittently highlighted in Kansas City

In 1997, Robert Altman created an anthology television series called Gun, which followed the path of a firearm as it moved from owner to owner. I never saw the series, which features performances by James Gandolfini, Rosanna Arquette, Martin Sheen, Jennifer Tilly, Brooke Adams and many others—Altman directed one episode, and others were directed by Ted Demme, Peter Horton, Jeremiah Chechik, James Foley and James Sadwith. But my sister-in-law gave me the DVD collection of the short-lived series six episodes, so I look forward to spinning those discs very soon.

THE GINGERBREAD MAN (1998) COOKIE’S FORTUNE (1999) DR. T AND THE WOMEN (2000)

In the wake of Kansas City’s status as a non-event at the box-office, and its critical dismissal, Altman found himself flirting with marginalization once again. He was obviously looking for a popular hit when he was hired to direct a film based on an original, and apparently discarded, story by John Grisham, and when he delivered The Gingerbread Man he found himself at odds with the studios again, who were threatening to wrestle final cut away from the master filmmaker based on a series of poor preview screenings. Aside from why the suits expected an Altman film to test well with audiences recruited from local shopping malls, one has to wonder what the studio thought it would be getting when it hired Altman for the project (it’s the old Popeye question rearing its ugly head again). But bad reputation aside, The Gingerbread Man is a very effective thriller, and Altman takes full advantage of the Savannah setting to soak the film in as much Southern ambience as the screen can hold, shaming Clint Eastwood’s film of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil in the process. When I saw this in the theater I remember thinking how exciting it was to see Altman, still at the top of his game, directing what can be described as a legal potboiler and seeing how well and exciting the results could be. What was that Pauline Kael comment about Altman making bread from stones by use of his magic as a director? She said it of Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, but in his directing of a stellar cast—this may be Kenneth Branagh’s last tolerable appearance on screen, and everyone from Robert Downey Jr. to Robert Duvall are used, in small roles, for utmost chilling effect—it’s certainly true of The Gingerbread Man as well.

In the wake of Kansas City’s status as a non-event at the box-office, and its critical dismissal, Altman found himself flirting with marginalization once again. He was obviously looking for a popular hit when he was hired to direct a film based on an original, and apparently discarded, story by John Grisham, and when he delivered The Gingerbread Man he found himself at odds with the studios again, who were threatening to wrestle final cut away from the master filmmaker based on a series of poor preview screenings. Aside from why the suits expected an Altman film to test well with audiences recruited from local shopping malls, one has to wonder what the studio thought it would be getting when it hired Altman for the project (it’s the old Popeye question rearing its ugly head again). But bad reputation aside, The Gingerbread Man is a very effective thriller, and Altman takes full advantage of the Savannah setting to soak the film in as much Southern ambience as the screen can hold, shaming Clint Eastwood’s film of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil in the process. When I saw this in the theater I remember thinking how exciting it was to see Altman, still at the top of his game, directing what can be described as a legal potboiler and seeing how well and exciting the results could be. What was that Pauline Kael comment about Altman making bread from stones by use of his magic as a director? She said it of Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, but in his directing of a stellar cast—this may be Kenneth Branagh’s last tolerable appearance on screen, and everyone from Robert Downey Jr. to Robert Duvall are used, in small roles, for utmost chilling effect—it’s certainly true of The Gingerbread Man as well.  Cookie’s Fortune and Dr. T and the Women find Altman continuing his expansive mapping of the ties and fulfillments of community and family, completing an unofficial trilogy of films positively marinating in the ambience and local flavor of their specifically Southern settings. (It’s interesting to look back on Altman’s career and see how many of his movies were inseparable from their location, almost as if the place where the action plays out is as important a character, in a metaphoric and sometimes even a literal sense, as the speaking roles inhabited by actors.) Cookie effectively revisits a kind of Wilderian (Thornton, not Billy) small-town farce and mixes it up with a liberal dash of Harper Lee, producing the closest thing to a grass-roots art-house hit Altman would have since the mid ‘70s.

Cookie’s Fortune and Dr. T and the Women find Altman continuing his expansive mapping of the ties and fulfillments of community and family, completing an unofficial trilogy of films positively marinating in the ambience and local flavor of their specifically Southern settings. (It’s interesting to look back on Altman’s career and see how many of his movies were inseparable from their location, almost as if the place where the action plays out is as important a character, in a metaphoric and sometimes even a literal sense, as the speaking roles inhabited by actors.) Cookie effectively revisits a kind of Wilderian (Thornton, not Billy) small-town farce and mixes it up with a liberal dash of Harper Lee, producing the closest thing to a grass-roots art-house hit Altman would have since the mid ‘70s. And Dr. T and the Women, a retelling of the story of Job, with Job as a put-upon but ever gracious gynecologist at the center of a small universe of eccentric femininity, left the director open to even more accusations of misogyny than usual. Altman’s movie has a cast of female (and male) characters that are given respect through the way the director allows them to light up Dr. T’s universe even as they unwittingly begin to suffocate it, and they are given enough room to display foibles and behavior that may be funny, insipid, ridiculous or noble, none of which seems to indicate venomous disregard on the part of the director. Not that you'd know this by reading film critic Manohla Dargis, however. I remember writing a letter to Dargis, then the senior film editor at the L.A. Weekly, the week the film premiered. In her brief capsule review, the critic felt compelled to condemn outright what she took to be Altman’s suffocating fear of and contempt for women allegedly on display in this warmhearted comedy. The gist of her argument seemed to be built around the idea that it was patently offensive that any man should build a movie around so many women and not present each and every one of them with anything but sober respect and deference. Dargis then moved on to inform all of us who had the misfortune of believing Altman to be a great director that, in fact, he hadn’t made a good movie since The Long Goodbye. I also remember I wasn’t the only reader who wrote in response to that absurd claim, and I salute the Weekly for allowing us to call this usually reliable and very intelligent critic on the carpet publicly for the knee-jerk reactionary tone of her comments. As for Dr. T, the movie ends on a jarring note, to be sure, as if a jazz piece suddenly ended with the unexpected flourish of an operatic aria, but it nonetheless fulfills Dr. T.’s, and Altman’s, wonder and awe at the feminine mystery and sends the movie off on a thrillingly high note.

And Dr. T and the Women, a retelling of the story of Job, with Job as a put-upon but ever gracious gynecologist at the center of a small universe of eccentric femininity, left the director open to even more accusations of misogyny than usual. Altman’s movie has a cast of female (and male) characters that are given respect through the way the director allows them to light up Dr. T’s universe even as they unwittingly begin to suffocate it, and they are given enough room to display foibles and behavior that may be funny, insipid, ridiculous or noble, none of which seems to indicate venomous disregard on the part of the director. Not that you'd know this by reading film critic Manohla Dargis, however. I remember writing a letter to Dargis, then the senior film editor at the L.A. Weekly, the week the film premiered. In her brief capsule review, the critic felt compelled to condemn outright what she took to be Altman’s suffocating fear of and contempt for women allegedly on display in this warmhearted comedy. The gist of her argument seemed to be built around the idea that it was patently offensive that any man should build a movie around so many women and not present each and every one of them with anything but sober respect and deference. Dargis then moved on to inform all of us who had the misfortune of believing Altman to be a great director that, in fact, he hadn’t made a good movie since The Long Goodbye. I also remember I wasn’t the only reader who wrote in response to that absurd claim, and I salute the Weekly for allowing us to call this usually reliable and very intelligent critic on the carpet publicly for the knee-jerk reactionary tone of her comments. As for Dr. T, the movie ends on a jarring note, to be sure, as if a jazz piece suddenly ended with the unexpected flourish of an operatic aria, but it nonetheless fulfills Dr. T.’s, and Altman’s, wonder and awe at the feminine mystery and sends the movie off on a thrillingly high note. (Quiet Bubble takes on Dr. T and the Women for the Altman Blog-a-Thon and has lots of interesting insight on how the movie works as a portrait of Dallas.)

GOSFORD PARK (2001) This is Altman returning with potency and piquancy to the role of genre-buster-- Gosford Park, by outward appearances, owes much to the Agatha Christie-Masterpiece Theatre template. But in most every way it offers itself up as a call out to those forms from the past while regarding them with glancing blows and a healthy disinterest in the creaky mechanisms of their plot-driven machinery—Altman’s far more interested in throwing this group together, privileged, pretentious society and the equally oppressive social strata operating throughout the servants’ quarters, to see what sticks. (It’s one of the delicious observations one can make about the film, which Altman never presses, that there is never a point during the main body of the film when there is not a servant present. The plot, ostensibly centered on a murder mystery, has barely had a chance to pick up steam before Altman deflates it by introducing a detective who cannot break through the contempt in which he is held by the various members of the house who are now suspects. His character eventually falls to the sidelines, having solved nothing, and we’re left to watch the real answer to the mystery coalesce around a group of servants who reveal, in the privacy of their chambers, rather than before a rapt audience in the study, the real background of the film’s fatal events. The film’s narrative revelation is powerfully acted, and it sends ripples back through what we know, or thought we knew to be true, about the ways the upstairs half are connected to the servants. None of these society hangers-on are doing much more than clinging to the proprieties of a dominant British society clearly on the wane, and none are willing to admit to their various states of insolvency which places them, at least on a monetary scale, much closer to the downstairs servants than they’d ever care to be made public. The Gosford Park mansion servants, on the other hand, continue to operate within this familiar structure more out of a sense of historical habit than owing to being subject to any real financial or societal privilege on the part of this “ruling class.” This may be Altman’s most deceptively effortless film—like a true master, he evokes Renoir’s The Rules of the Game without ever presuming to claim anything more for the quality and durability of his own film than a certain “guilt” by association. And it feels as if the pieces, surely as arduously “choreographed” for the camera and assembled from various levels of improvisation, simply glided together by some sort of majestic design. Altman has imposed his fractured, observational technique on the very familiar skeleton of the British boarding room mystery and somehow managed to make it play very similarly to a life collage like Nashville. For his efforts, he’d one last time be nominated for a competitive Oscar, but Altman and the film would lose to Ron Howard and A Beautiful Mind. However, screenwriter Julian Fellowes would step up to the podium to accept the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

GOSFORD PARK (2001) This is Altman returning with potency and piquancy to the role of genre-buster-- Gosford Park, by outward appearances, owes much to the Agatha Christie-Masterpiece Theatre template. But in most every way it offers itself up as a call out to those forms from the past while regarding them with glancing blows and a healthy disinterest in the creaky mechanisms of their plot-driven machinery—Altman’s far more interested in throwing this group together, privileged, pretentious society and the equally oppressive social strata operating throughout the servants’ quarters, to see what sticks. (It’s one of the delicious observations one can make about the film, which Altman never presses, that there is never a point during the main body of the film when there is not a servant present. The plot, ostensibly centered on a murder mystery, has barely had a chance to pick up steam before Altman deflates it by introducing a detective who cannot break through the contempt in which he is held by the various members of the house who are now suspects. His character eventually falls to the sidelines, having solved nothing, and we’re left to watch the real answer to the mystery coalesce around a group of servants who reveal, in the privacy of their chambers, rather than before a rapt audience in the study, the real background of the film’s fatal events. The film’s narrative revelation is powerfully acted, and it sends ripples back through what we know, or thought we knew to be true, about the ways the upstairs half are connected to the servants. None of these society hangers-on are doing much more than clinging to the proprieties of a dominant British society clearly on the wane, and none are willing to admit to their various states of insolvency which places them, at least on a monetary scale, much closer to the downstairs servants than they’d ever care to be made public. The Gosford Park mansion servants, on the other hand, continue to operate within this familiar structure more out of a sense of historical habit than owing to being subject to any real financial or societal privilege on the part of this “ruling class.” This may be Altman’s most deceptively effortless film—like a true master, he evokes Renoir’s The Rules of the Game without ever presuming to claim anything more for the quality and durability of his own film than a certain “guilt” by association. And it feels as if the pieces, surely as arduously “choreographed” for the camera and assembled from various levels of improvisation, simply glided together by some sort of majestic design. Altman has imposed his fractured, observational technique on the very familiar skeleton of the British boarding room mystery and somehow managed to make it play very similarly to a life collage like Nashville. For his efforts, he’d one last time be nominated for a competitive Oscar, but Altman and the film would lose to Ron Howard and A Beautiful Mind. However, screenwriter Julian Fellowes would step up to the podium to accept the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. THE COMPANY (2002) By this point in my life, I was now the father of two girls, my second coming in August of the year this movie was released, and seeing movies on the big screen was becoming a much more difficult prospect. I tried mightily to get to see The Company on a big screen, but circumstances would not allow for it and I ended up seeing the film on DVD. I can only imagine that drinking in the imagery offered up in this documentary-style fictional account of the ins and outs of a fictional dance troupe (realized with the full cooperation of the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago) would have been an intoxicating experience, because even seeing it at home it was clear that the film I saw, an impressionistic drama that eschews melodrama and makes room for some lovely, unspoiled ballet performances, was probably the most visually gorgeous of 2002, and certainly one of Altman’s most invigorating visual/aural experiments. (This is the man who directed McCabe and Mrs. Miller, California Split, Nashville and 3 Women, remember, so that kind of praise is well-considered and sky-high indeed.) Altman, in concert with cinematographer Andrew Dunn, shoots the movie in a silken, almost weightless style on high-definition video, and it proves the lie to the generally accepted wisdom that video is incapable of registering the kind of depth and richness of imagery that film routinely can. The Company imbues scenes that could have been so very routine in the hands of anyone else and nimbly transforms them into gossamer spectacles of living, breathing, graphically wondrous, layered, flowing imagery that, incredibly, never comes off as precious, and indeed defuses some of the screenplay’s flirtations with familiar backstage drama. Neve Campbell and the rest of the dancing cast seem supremely lacking in self-consciousness. These people seem honestly observed, in a documentary sense, and therefore astounding to behold, even as they, so gifted with movement and grace, move about the world off-stage in a manner familiar to most of the rest of us. As a result, Malcolm McDowell, as the company’s mercurial artistic director and chief choreographer, has plenty of opportunity to stand out amongst the cast without unleashing his most outrageous impulses to go soaring over the top. Even his face at rest is so much more than what the other actors and dancers have to offer that he has to do very little to seem the most magnetic force of nature in the film. I’m not sure where The Company belongs in the ranks of Altman’s films—somewhere near the top, I’d say—but wherever it lands, it is thrilling to behold for its leaps and pirouettes, its sensitivity and agility, for its seemingly boundless capacity for beauty that seems to materialize out of the deceptively ordinary, right before our eyes. It is the work of a man who was 76 years old when it was made, and it makes the work of arduous and uninspired hacks half his age seem downright geriatric in comparison. Thirty-two years after M*A*S*H, Robert Altman was still showing the suits and the hot-shots how it can be done, and leaving most of them in the dust while he’s doing it.

THE COMPANY (2002) By this point in my life, I was now the father of two girls, my second coming in August of the year this movie was released, and seeing movies on the big screen was becoming a much more difficult prospect. I tried mightily to get to see The Company on a big screen, but circumstances would not allow for it and I ended up seeing the film on DVD. I can only imagine that drinking in the imagery offered up in this documentary-style fictional account of the ins and outs of a fictional dance troupe (realized with the full cooperation of the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago) would have been an intoxicating experience, because even seeing it at home it was clear that the film I saw, an impressionistic drama that eschews melodrama and makes room for some lovely, unspoiled ballet performances, was probably the most visually gorgeous of 2002, and certainly one of Altman’s most invigorating visual/aural experiments. (This is the man who directed McCabe and Mrs. Miller, California Split, Nashville and 3 Women, remember, so that kind of praise is well-considered and sky-high indeed.) Altman, in concert with cinematographer Andrew Dunn, shoots the movie in a silken, almost weightless style on high-definition video, and it proves the lie to the generally accepted wisdom that video is incapable of registering the kind of depth and richness of imagery that film routinely can. The Company imbues scenes that could have been so very routine in the hands of anyone else and nimbly transforms them into gossamer spectacles of living, breathing, graphically wondrous, layered, flowing imagery that, incredibly, never comes off as precious, and indeed defuses some of the screenplay’s flirtations with familiar backstage drama. Neve Campbell and the rest of the dancing cast seem supremely lacking in self-consciousness. These people seem honestly observed, in a documentary sense, and therefore astounding to behold, even as they, so gifted with movement and grace, move about the world off-stage in a manner familiar to most of the rest of us. As a result, Malcolm McDowell, as the company’s mercurial artistic director and chief choreographer, has plenty of opportunity to stand out amongst the cast without unleashing his most outrageous impulses to go soaring over the top. Even his face at rest is so much more than what the other actors and dancers have to offer that he has to do very little to seem the most magnetic force of nature in the film. I’m not sure where The Company belongs in the ranks of Altman’s films—somewhere near the top, I’d say—but wherever it lands, it is thrilling to behold for its leaps and pirouettes, its sensitivity and agility, for its seemingly boundless capacity for beauty that seems to materialize out of the deceptively ordinary, right before our eyes. It is the work of a man who was 76 years old when it was made, and it makes the work of arduous and uninspired hacks half his age seem downright geriatric in comparison. Thirty-two years after M*A*S*H, Robert Altman was still showing the suits and the hot-shots how it can be done, and leaving most of them in the dust while he’s doing it. On March 5, 2006, Robert Altman accepted an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement, and graciously accepted the award while at the same time admitting he felt like, while these kinds of awards were usually signals that it was all pretty much over, he still had a long way left to go, and proceeded to offer evidence of the play he’s directing in London, and the new movie he’s about to unveil, as evidence supporting that assertion. Altman took the stage after being introduced by Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep in what has to be considered the wittiest and most nimbly executed bit of acting ever to grace the Oscar stage—they sharply approximated the kind of overlapping, head-butting dialogue that Altman pioneered in a long introduction that name-checked Nashville (twice), Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean and scores of other Altman films with which the audience in the Kodak Theater was probably only sketchily familiar. And it seemed like it took those starched folks in the Kodak an awfully long time to get the joke, too. The introduction, the slightly flummoxed Oscar audience, and Altman’s generous speech (during which he revealed a heart transplant he underwent 10 years ago and likened his filmmaking process to gathering a group of friends on the beach to build an elaborate sand castle, only to watch the tide sweep it all away in the twilight), all added up to perhaps the single most wonderful moment in the history of the Academy Awards.

On March 5, 2006, Robert Altman accepted an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement, and graciously accepted the award while at the same time admitting he felt like, while these kinds of awards were usually signals that it was all pretty much over, he still had a long way left to go, and proceeded to offer evidence of the play he’s directing in London, and the new movie he’s about to unveil, as evidence supporting that assertion. Altman took the stage after being introduced by Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep in what has to be considered the wittiest and most nimbly executed bit of acting ever to grace the Oscar stage—they sharply approximated the kind of overlapping, head-butting dialogue that Altman pioneered in a long introduction that name-checked Nashville (twice), Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean and scores of other Altman films with which the audience in the Kodak Theater was probably only sketchily familiar. And it seemed like it took those starched folks in the Kodak an awfully long time to get the joke, too. The introduction, the slightly flummoxed Oscar audience, and Altman’s generous speech (during which he revealed a heart transplant he underwent 10 years ago and likened his filmmaking process to gathering a group of friends on the beach to build an elaborate sand castle, only to watch the tide sweep it all away in the twilight), all added up to perhaps the single most wonderful moment in the history of the Academy Awards. As a tribute to Altman’s Oscar, Brian Darr used the occasion of the Altman Blog-a-Thon to imagine an Academy Awards ceremony entirely devoted to nominees derived from Altman’s films. It’s a wonderful way to remember all the performances that have helped make Altman’s films special, and in reading Brian’s list you’ll surely be inspired to add some nominees of your own.

The Altman Weekend Blog-a-Thon, which officially commenced last Friday, March 3, and for which this installment of “81 Candles for Robert Altman” will probably be the last, straggling entry, produced some really outstanding work in honor of this maverick director. I’ve noted a lot of outstanding entries as they have pertained to films I’ve discussed in this section, but those are by no means all that the Blog-a-Thon produced. Here are some others, courtesy of Matt Zoller Seitz, ringmaster of the Altman Blog-a-Thon:

N.Y. Film Critic examines Nashville song by song…

N.Y. Film Critic examines Nashville song by song…Jdanspa Wyksui encounters Nashville with fresh eyes…

and Michael Guillen at The Evening Class relates an evening with Altman watching Nashville at the Castro Theater in San Francisco.

Three posts in which to dive into McCabe and Mrs. Miller, courtesy of Bill Roundtree, The Listening Ear and Matt Zoller Seitz.

SLIFR reader and excellent blogger Machine Gun McCain opens up the vaults for a fascinating look at a post-3 Women short film directed by Altman for Saturday Night Live at More Than Meets the Mogwai.

Girish traverses the pre-M*A*S*H Altman with a consideration of one of the director’s least-known films, one which I haven’t seen myself-- That Cold Day in the Park starring Sandy Dennis and Michael Burns.

Thanks to Quiet Bubble again for pointing the way toward a voice of dissent amidst all the hosannahs and other hubbub surrounding Altman during his Oscar weekend: Daryl Chin on Altman and actresses.

On the subject of nudity, two fascinating posts, one from Liverputty which chronicles, with plenty of full-color illustrations, the history of flesh in Altman’s films, and a consideration of Julianne Moore’s memorable bottomless appearance in Short Cuts, courtesy of Five Branch Tree.

Filmbrain at Like Anna Karina’s Sweater surprises himself with his reaction to H*E*A*L*T*H.

David Lowery at Drifting on Images and O.C. and Stiggs.

That Little Round-Headed Boy offers a fascinating consideration of Popeye and boldly links it to another film in the Altman canon, its relationship to which only seems obvious after TLRHB makes his very cogent case.

And the analysis of Secret Honor doesn’t get much better than Tom Sutpen’s excellent piece on the film at If Charlie Parker Were a Gunslinger…

The Listening Ear relates why Robert Altman is key to his love of not just the director’s work, but of all movies.

And for those of you (and if you’ve read this far, I imagine you’re one of them) who are eagerly anticipating what’s next from this master director, last week Cinematical unveiled news of the recently released trailer for Altman’s upcoming A Prairie Home Companion. You can see the trailer by clicking here. Someone on IMDb has already checked in, proclaiming it’s “the movie of the year.” Well, all premature hyperbole aside, it’s hard to see how anyone who has spent their life watching Altman’s films could fail to get excited at what this fantastically tantalizing trailer has to offer. Altman got his honorary Oscar, true, but it looks like he’s still got plenty of wine in the old skin yet, and that’s truly an excellent prospect upon which to ruminate.

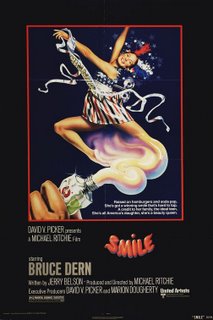

And for those of you (and if you’ve read this far, I imagine you’re one of them) who are eagerly anticipating what’s next from this master director, last week Cinematical unveiled news of the recently released trailer for Altman’s upcoming A Prairie Home Companion. You can see the trailer by clicking here. Someone on IMDb has already checked in, proclaiming it’s “the movie of the year.” Well, all premature hyperbole aside, it’s hard to see how anyone who has spent their life watching Altman’s films could fail to get excited at what this fantastically tantalizing trailer has to offer. Altman got his honorary Oscar, true, but it looks like he’s still got plenty of wine in the old skin yet, and that’s truly an excellent prospect upon which to ruminate.Finally, from me, when I think of the films of Robert Altman, I think not only of the ones he’s directed, but the ones that have been made in his shadow. And when I start running down a list of those titles, everything from the collected works of Alan Rudolph and Paul Thomas Anderson to Matt Zoller Seitz’s terrific ensemble piece Home (which I’ll be reviewing next week, in conjunction with an interview with the critic/filmmaker), it becomes even clearer the importance this director has had and continues to have for contemporary cinema. Even television, on shows as diverse as Hill Street Blues, St. Elsewhere, L.A. Law and most recently, Deadwood, bears traits and stylistic strategies directly traceable to Altman. But I’ve always felt that the best movie ever made in the shadow of Robert Altman’s influence was, and still is, Michael Ritchie’s Smile. Released four months after Nashville, in October 1975, Ritchie’s film followed the pattern of his own Downhill Racer and The Candidate, part of a series of films he made in the ‘70s whose mission it was to dissect and examine the peculiarly American strain of sometimes vicious competition in sports and, in Smile, the world of small-town beauty pageants. (Ritchie’s follow-up to Smile would be the brilliant baseball comedy The Bad News Bears.)

The knife with which Ritchie mounts that satiric dissection was never sharper than it was in Smile, yet the movie never seems bitter or callous, and even its most cartoonish characters are allowed their moments of humanity and understanding—the list includes Bruce Dern’s used-car salesman, who is the pageant’s biggest business supporter, Barbara Feldon as a myopic pageant coordinator, Annette O’Toole as the most ruthless of all the two-faced pageant contestants, and even legendary choreographer Michael Kidd as the choreographer brought in to whip the show into shape, who at first seems like a prototypical show-biz bastard, but displays perhaps the most humane gesture in the entire film when an accident sidelines one of the contestants. Smile even looks at times like an Altman film, and by early 1975, when the film was shot, M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud, McCabe and Mrs. Miller Images, The Long Goodbye and California Split had already infiltrated cinematic culture, so there’s little doubt that Michael Ritchie was influenced by the director’s style, consciously or not. After all, it was still the mid ‘70s, pre-Jaws, and though the time of this golden age of American filmmaking was nearing its end, it was still a time when it still wasn’t necessarily frowned upon to wear the influences of films that were less than box-office gold on your directorial sleeves.

The knife with which Ritchie mounts that satiric dissection was never sharper than it was in Smile, yet the movie never seems bitter or callous, and even its most cartoonish characters are allowed their moments of humanity and understanding—the list includes Bruce Dern’s used-car salesman, who is the pageant’s biggest business supporter, Barbara Feldon as a myopic pageant coordinator, Annette O’Toole as the most ruthless of all the two-faced pageant contestants, and even legendary choreographer Michael Kidd as the choreographer brought in to whip the show into shape, who at first seems like a prototypical show-biz bastard, but displays perhaps the most humane gesture in the entire film when an accident sidelines one of the contestants. Smile even looks at times like an Altman film, and by early 1975, when the film was shot, M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud, McCabe and Mrs. Miller Images, The Long Goodbye and California Split had already infiltrated cinematic culture, so there’s little doubt that Michael Ritchie was influenced by the director’s style, consciously or not. After all, it was still the mid ‘70s, pre-Jaws, and though the time of this golden age of American filmmaking was nearing its end, it was still a time when it still wasn’t necessarily frowned upon to wear the influences of films that were less than box-office gold on your directorial sleeves.  As much as I admire Magnolia, or Choose Me, or Songwriter, or Punch-Drunk Love, Smile strikes me as the most organic, the most natural, the least self-conscious overflow of the Altman sensibility onto that of another director, and like Altman’s films of the period it has not lost any of its likeability, the astringency of its humor, or its potency as a consideration of the social landscape which it examines in its own sharp and shaggy manner. It’s also one of the best and most overlooked films of the ‘70s, and it’s available on a very inexpensive MGM DVD, so I hope you’ll look it up one day and see if you don’t agree with me that it really is the Best Robert Altman Film Not Actually Directed by Robert Altman.

As much as I admire Magnolia, or Choose Me, or Songwriter, or Punch-Drunk Love, Smile strikes me as the most organic, the most natural, the least self-conscious overflow of the Altman sensibility onto that of another director, and like Altman’s films of the period it has not lost any of its likeability, the astringency of its humor, or its potency as a consideration of the social landscape which it examines in its own sharp and shaggy manner. It’s also one of the best and most overlooked films of the ‘70s, and it’s available on a very inexpensive MGM DVD, so I hope you’ll look it up one day and see if you don’t agree with me that it really is the Best Robert Altman Film Not Actually Directed by Robert Altman. Thanks for hanging in there with me through this four-part retrospective. I hope it’s been as worthwhile for you as it has been for me!

"Finally, do you feel, as Blaaagh exclaimed when he called me

ReplyDeleteimmediately after Robert Altman’s speech, that the director’s moment,

complete with introduction by the brilliantly overlapping collision

between Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep, was perhaps the finest moment in

Oscar history?"

Um. Well, it was wonderful, original and perfect. In a crazy, exuberant

(though entirely different) way it was right up there with Sammy Davis,

Jr.'s response to having been handed the wrong envelope when he was a

presenter in the early '60s.

[But to me the finest moment in Oscar history -- or, at least, in my

forty-three years of watching the ceremony on television -- remains the

eloquent, unexpected tribute paid to Barbara Stanwyck by William Holden

when the two actors presented the Sound award in 1978.]

Incidentally, it's well known that Altman was deemed "uninsurable" for A

PRAIIE HOME COMPANION -- hence P.T. Anderson's on-set presence as

"stand-by director." I can't but wonder whether this occurrence

influenced his decision to publicly reveal his heart transplant of a

decade ago. Now a formal "risk," the filmmaker may have decided there

was no longer a reason to conceal this.

At any rate, he seemed healthy and fairly vigorous on the Kodak theater

stage...

"Exercise Your Right to Vote" was, of course, first heard in HEALTH.

Nice essays.

-- Griff

Good point about Altman revealing the heart transplant. And I had forgotten that "Exercise Your Right to Vote" had first appeared in HEALTH. Thanks for the reminder.

ReplyDeleteCan you refresh my memory about that Barbara Stanwyck/William Holden Oscar moment?