The last encounter I had with anyone here in Los Angeles involving race or cultural diversity came while helping out in my daughter’s kindergarten class last week. I called her name and attached to it the appellative “-chan,” a familiar term of endearment in the Japanese language (my daughter is half Japanese). My daughter’s teacher looked up at me and asked me what I said. I repeated it, and she told me, with some delight, that in Armenian there is a similar appellative, used in exactly the same way, pronounced “-jan.” It was a pleasant exchange, an unexpected connection between two cultures and peoples I’d always assumed were about as far apart as two cultures and peoples could get. There was no tension, no unease, no anger bubbling just under the surface that eventually exploded in ugly epithets and violence. It was a simple, everyday occurrence, the sort for which there is simply no room in Paul Haggis’ widely admired, overwrought, fatally didactic and schematic, frequently absurd after-school special entitled Crash.

The last encounter I had with anyone here in Los Angeles involving race or cultural diversity came while helping out in my daughter’s kindergarten class last week. I called her name and attached to it the appellative “-chan,” a familiar term of endearment in the Japanese language (my daughter is half Japanese). My daughter’s teacher looked up at me and asked me what I said. I repeated it, and she told me, with some delight, that in Armenian there is a similar appellative, used in exactly the same way, pronounced “-jan.” It was a pleasant exchange, an unexpected connection between two cultures and peoples I’d always assumed were about as far apart as two cultures and peoples could get. There was no tension, no unease, no anger bubbling just under the surface that eventually exploded in ugly epithets and violence. It was a simple, everyday occurrence, the sort for which there is simply no room in Paul Haggis’ widely admired, overwrought, fatally didactic and schematic, frequently absurd after-school special entitled Crash.

I’m not naïve enough to suggest that racial tension in the most segregated city in America is outside of my experience—if it ever was before (and it wasn’t), in the post Rodney King-O.J. Simpson era it is impossible to live in Los Angeles and not be aware of the kind of cultural divisions that often seem to be tearing the city apart from the inside out. But it’s just as naïve, self-serving and dramatically shortsighted to set up an entire movie populated by people who function only to embody all the various elements of bigotry and prejudice and intolerance which make up Haggis’ cobbled-together thesis, the bottom line of which seems to be, “Racism is wrong, and we are all capable of it.” A radical idea on which to construct a big, important social melodrama, or a safe platitude around which to twist and turn a convoluted narrative based on a specious metaphor designed to ensure everyone who leaves the theater will be convinced they’ve seen something significant and soul-changing? When a morose detective played by Don Cheadle opines, not five minutes into the film, about Los Angelenos, “We’re always behind this metal and glass. It’s the sense of touch. I think we miss that sense of touch so much that we crash into each other just so we can feel something”—and, yes, he’s just gotten into a fender-bender—I felt like shutting the film down, because I could feel Haggis already clobbering me on the head, insisting that I understand that he’s serious, dammit.

Haggis’ strategy is to alternate between the stories of 15 or 20 different characters as they literally and figuratively crash into each other over the course of the movie, and since none of them have any inner lives, all any of them ever talks about are hot-button issues of race and intolerance. Haggis writes scene after scene of position-paper dialogue masking as conversation, and after a very short while you begin to realize that these 15-20 characters must be the only citizenry in Los Angeles, because they keep stumbling over—I’m sorry, crashing into each other in ridiculous coincidence after ridiculous coincidence. The racist cop (Matt Dillon) who feels up the wife (Thandie Newton) of a black TV director (Terrence Howard) at a traffic stop saves her from a fiery car accident the next day. The same black carjackers (Larenz Tate and the representatively named rapper-actor Ludacris, who likes to argue about hip-hop culture and black-on-black crime and being stereotyped by whites between jobs) who steal an SUV belonging to the district attorney (Brendan Fraser) and his shrew of a wife (Sandra Bullock) later jack the SUV of the above-mentioned TV director, leading to a patently absurd scene in a which the ex-partner of the racist cop (Ryan Phillippe), after a lengthy chase down residential streets, convinces the rest of the pursuing officers to let him off with a warning. The cops have mistakenly assumed that the director, because he’s black, has done something wrong-- he’s really been trying to wrest control of the vehicle from Ludacris, who hides in the front seat, undiscovered, while Phillippe engineers Howard’s release. Later, Phillippe, a good liberal, will gun down one of these same carjackers due to a knee-jerk response based on the man’s race. The dead car thief turns out to be the brother of another major character, and on and on and on.

Those who would defend Crash might dismiss these constant coincidental meetings as thematically relevant, and the interlocking stories as parables. This might be a way of suggesting that even though they are filmed “realistically” and we are meant to take Crash as a portrait ripped fresh and bleeding from the streets-- The Way We Live Now!-- they don’t really have to be believable in a dramatic sense because they exist primarily to teach us something. (That “whooshing” sound is the wind going right out of my sails.) Unfortunately, those stories don’t really interlock so much as, yes, crash together, due largely to Haggis’ ham-fisted mise-en-scene, his tin ear and the movie’s flaccid, predictable editorial rhythms (You may ask yourself, for example, why we're not allowed to see a scene between Newton and Howard where he expresses his concern that she almost lost her life in a car accident. It’s not there because Haggis isn’t interested in these people as people, only in terms of how they flesh out his thesis—much more important to see the scene where Howard stands up to the Man and regains his dignity, even if it is one of the most unbelievable scenes in the entire movie.) The film is rigged to produce a response to premises-- racism is wrong, all of us have the capacity to change-- with which most of the film’s viewers probably already agree, and the zeal with which people have taken to this movie might make others who end up less impressed think that to reject the movie’s clunky drama-turgid-cal arguments is tantamount to siding with the devil of intolerance. I’d call it standing up for cogent, clearheaded analysis and vivid storytelling.

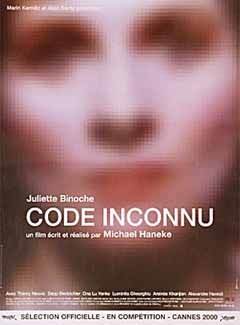

Those who would defend Crash might dismiss these constant coincidental meetings as thematically relevant, and the interlocking stories as parables. This might be a way of suggesting that even though they are filmed “realistically” and we are meant to take Crash as a portrait ripped fresh and bleeding from the streets-- The Way We Live Now!-- they don’t really have to be believable in a dramatic sense because they exist primarily to teach us something. (That “whooshing” sound is the wind going right out of my sails.) Unfortunately, those stories don’t really interlock so much as, yes, crash together, due largely to Haggis’ ham-fisted mise-en-scene, his tin ear and the movie’s flaccid, predictable editorial rhythms (You may ask yourself, for example, why we're not allowed to see a scene between Newton and Howard where he expresses his concern that she almost lost her life in a car accident. It’s not there because Haggis isn’t interested in these people as people, only in terms of how they flesh out his thesis—much more important to see the scene where Howard stands up to the Man and regains his dignity, even if it is one of the most unbelievable scenes in the entire movie.) The film is rigged to produce a response to premises-- racism is wrong, all of us have the capacity to change-- with which most of the film’s viewers probably already agree, and the zeal with which people have taken to this movie might make others who end up less impressed think that to reject the movie’s clunky drama-turgid-cal arguments is tantamount to siding with the devil of intolerance. I’d call it standing up for cogent, clearheaded analysis and vivid storytelling.  Haggis’ movie has drawn comparison with other life-in-L.A. mosaics like Alan Rudolph’s fuzzy, unfocused Welcome to L.A., Robert Altman’s misguided and condescending Short Cuts and, the cream of the crop, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, which found ever more interesting ways to spin characters that resembled real human beings through a visually arresting narrative that hit on its own concerns in a fluidly charged way quite the opposite of how Crash throttles its big issues to the ground. Anderson, in Magnolia recognizes that one aspect of an issue or a person does not constitute that whole person, and he creates a visual/aural tapestry that, seen whole, is reflective of a sensibility based on dramatic and emotional truth, of searching for the connections that people make and following them in order to find out where they go, not because you’ve already decided where they’re headed and what they mean (if anything). At the top of this particular hill must be Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown, probably the best example of this kind of mapping of the ways in which people touch and influence and enhance and destroy each other’s lives, often without ever knowing it, all as a condition, a symptom, of living life in modern, racially and culturally integrated cities. What’s intriguing, as a matter of comparison not only with Crash but with the other films as well, is how Haneke charts the movement of his characters. Where Altman or Rudolph or Anderson or Haggis might insist that the constant bumping up against each other within the framework of the urban world they portray is where their films derive, or at least begin to extrapolate their meaning, Haneke sees it in precisely the opposite terms.

Haggis’ movie has drawn comparison with other life-in-L.A. mosaics like Alan Rudolph’s fuzzy, unfocused Welcome to L.A., Robert Altman’s misguided and condescending Short Cuts and, the cream of the crop, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, which found ever more interesting ways to spin characters that resembled real human beings through a visually arresting narrative that hit on its own concerns in a fluidly charged way quite the opposite of how Crash throttles its big issues to the ground. Anderson, in Magnolia recognizes that one aspect of an issue or a person does not constitute that whole person, and he creates a visual/aural tapestry that, seen whole, is reflective of a sensibility based on dramatic and emotional truth, of searching for the connections that people make and following them in order to find out where they go, not because you’ve already decided where they’re headed and what they mean (if anything). At the top of this particular hill must be Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown, probably the best example of this kind of mapping of the ways in which people touch and influence and enhance and destroy each other’s lives, often without ever knowing it, all as a condition, a symptom, of living life in modern, racially and culturally integrated cities. What’s intriguing, as a matter of comparison not only with Crash but with the other films as well, is how Haneke charts the movement of his characters. Where Altman or Rudolph or Anderson or Haggis might insist that the constant bumping up against each other within the framework of the urban world they portray is where their films derive, or at least begin to extrapolate their meaning, Haneke sees it in precisely the opposite terms.Code Unknown, well described in the opening credits as “a collection of incomplete tales of several journeys,” begins with a brief episode in which a group of deaf children attempt to interpret a visual representation of an emotion (“Alone,” “Hiding Place,” “Sad”). This sequence is followed immediately with a single long take that will handily encompass the characters who will, in varying degrees, inform the rest of the film. The camera glides laterally along a Parisian street as we observe a young man, Jean (Alexandre Hamidi), catch up to a young woman, an actress named Anne (Juliette Binoche) who is his older brother’s girlfriend. Jean expresses frustration about having to live with his father on their farm, for which his father expects him to eventually assume responsibility. Anne discourages the idea of Jean moving into the apartment she shares with Jean’s brother, but offers to let him rest there for the afternoon while she is out and gives him the pass code so that he can enter the building. (This is the film’s only explicit reference to a code, unknown or otherwise, and it’s enough to set up a fertile metaphor that the movie will bring to fruition in various incidental ways.) After parting with Anne, Jean walks the street, unsure of where to go, and in a burst of frustration hurls a crumpled sandwich bag into the lap of a woman (who we will later know as Maria, played by Luminata Gheorghiu) who sits begging for change near a storefront. The act is witnessed by Amadou (Ona Lu Yenke), a teacher of deaf students, who confronts Jean and demands he return and apologize to the woman. The police are quickly called, Anne reappears on the scene, and it’s not long before the police have (inaccurately) assessed the situation and Amadou has been arrested for attacking Jean. As a result of this one encounter, Amadou will spend time in jail (where, we find out later, he was beaten), Jean will sullenly retreat to his father’s farm, Maria will be deported to Romania when it is discovered she is in France illegally, and Anne proceeds on to a series of film auditions.

Rather than tracing his characters in a pattern like an interconnected web, taking them from the outside in toward an all-encompassing event or series of events that will tend to define them, Haneke, in Code Unknown approaches this central narrative event as if it were the point of impact on a shattered windshield, a center of pulverized glass, and follows the myriad ways in which these people fan out along the cracks toward experiences and destinations that may have been set in motion by that event but may also bear no real relationship to it. It is down these fractured, unpredictable paths that Haneke sets his characters, a strategy which sets the film itself up as a series of fragments, individual scenes not connected by conventional film grammar (dissolves, shock cutting, graphic continuity, etc.) that often begin and end abruptly, either just a moment or two into the significant action, or just a beat or two behind the completion of a thought or an action, separated by a brief moment of darkness. The director often refuses to make the connections between emerging characters and those we’ve already met clear—it may be a minute or two, or more, before we can adequately suss out who this new person is in relation to Jean, or Anne, or Amadou, or other more tangential characters. (At one point Anne is seen attending a funeral, and the moment when the realization hits as to who is being buried is devastating, in large part due to the offhanded way we’ve been made aware of this character’s presence earlier in the film.) Within that period of time when we’re assessing these connections, we’ve been taking in information about the environment and the different ways we’re allowed to see those characters that accrue and augment our understanding. There’s a striking scene, reminiscent of similar visual strategies Haneke uses in Cache, in which Anne is seen addressing an unseen man on a videotape—she becomes increasingly distraught, as it is becomes clear she’s been trapped in a room where she will be killed for the man’s entertainment, and only gradually, while watching Binoche’s magnificent face register an agonizing array of emotion, do we realize she’s auditioning for a suspense thriller.

Rather than tracing his characters in a pattern like an interconnected web, taking them from the outside in toward an all-encompassing event or series of events that will tend to define them, Haneke, in Code Unknown approaches this central narrative event as if it were the point of impact on a shattered windshield, a center of pulverized glass, and follows the myriad ways in which these people fan out along the cracks toward experiences and destinations that may have been set in motion by that event but may also bear no real relationship to it. It is down these fractured, unpredictable paths that Haneke sets his characters, a strategy which sets the film itself up as a series of fragments, individual scenes not connected by conventional film grammar (dissolves, shock cutting, graphic continuity, etc.) that often begin and end abruptly, either just a moment or two into the significant action, or just a beat or two behind the completion of a thought or an action, separated by a brief moment of darkness. The director often refuses to make the connections between emerging characters and those we’ve already met clear—it may be a minute or two, or more, before we can adequately suss out who this new person is in relation to Jean, or Anne, or Amadou, or other more tangential characters. (At one point Anne is seen attending a funeral, and the moment when the realization hits as to who is being buried is devastating, in large part due to the offhanded way we’ve been made aware of this character’s presence earlier in the film.) Within that period of time when we’re assessing these connections, we’ve been taking in information about the environment and the different ways we’re allowed to see those characters that accrue and augment our understanding. There’s a striking scene, reminiscent of similar visual strategies Haneke uses in Cache, in which Anne is seen addressing an unseen man on a videotape—she becomes increasingly distraught, as it is becomes clear she’s been trapped in a room where she will be killed for the man’s entertainment, and only gradually, while watching Binoche’s magnificent face register an agonizing array of emotion, do we realize she’s auditioning for a suspense thriller.Race is significant in Code Unknown, too, but the way Haneke integrates the reality of social relations into the mosaic of the film’s “narrative” boldly suggests, as Crash does not, that the viewer may have actually done some independent thinking on the subject before coming upon this film, and thus may be capable of filling in the spaces between glances and body language and intonation, allowing the story to tell itself so much more eloquently. When the police arrive on the scene and begin questioning Jean and Amadou, there’s an immediate resignation on Amadou’s part, a slight recessive quality in his body language, even as he remains confrontational, which says, “I know what’s coming, but I need you to hear me anyway.” Paul Haggis might have had Amadou begin haranguing the officers, Ludacris-style, about how a nigga always gets treated this way, immediately curdling the subtleties at work in the scene into hopeless grandstanding. It’s there in the eyes of the officers too, who must assert their authority while holding their physicality, and their disdain for Amadou as an assertive black man, in check for fear of creating a potentially more volatile situation. Haggis would have made sure Amadou’s girlfriend (who turns out to be white) was also present, so one of the officers could grope her in front of him, thus adding another series of humiliations onto the already loaded scenario.

But what may be even more important about the way Haneke plays the race card is the way that, when the matter of race does shift to the foreground, it may still not be the most significant element being discussed in the scene. Haneke doesn’t dilute the power of any scene by overemphasis, and certainly the one scene in Code Unknown that could be read as an explicit statement on race relations in an integrated city like Paris could just as easily be read, minute to minute, as a bitter comment on class, economics, sexual aggression, sex-based power or simple urban stress. On a Metro ride after a day of looping dialogue for an upcoming film, Anne is confronted by two young men, one of whom, unprovoked, zeroes in on her and begins haranguing her, accusing Anne of disregarding him based on his “common” status (he reveals after a few moments that he is an Arab). Anne quietly endures his increasingly aggressive and suggestive comments, but at the first opportunity she moves down to the end of the car to an empty seat. The young man follows her, sits next to her and continues his campaign of rage, while an older man sitting directly across the row stares straight ahead, clearly disgusted by the young man’s actions but unwilling to get in the middle of the confrontation. Finally, the young man spits in Anne’s face and begins to walk away, and the older man blocks his way and tells him, in Arabic, that he considers the young man an embarrassment. The hostility leaches out of the young man’s posture as he stands staring at the older man for an uncomfortable moment. He then passes out of the frame and presumably heads for the exit. Haneke’s camera holds on the older man, who has returned to his seat, and Anne, who is wiping her face with a handkerchief and trying to maintain her composure. The scene has been quiet just long enough that when the young man, from out of frame, makes a shocking, loud noise before leaving the train car meant only to unnerve both of them, it succeeds all too well. Anne’s reserve has been shattered, and she explodes in tearful sobs, through which she thanks the older man, who, we might guess, has been witness to this kind of behavior before.

The scene is a brilliant tour de force from Binoche, who creates high point after high point like this throughout the film. In a career full of exceptional performances, this is the very best work I’ve ever seen from her. But it’s Haneke’s triumph as well, as the scene turns out to be the emotional climax of the film, and a more powerful, elliptical way of summing up and addressing the concerns of the entire picture I couldn't imagine— the way the electricity of all these interwoven connections fires on the nerve endings of these characters to create meaning through experience, shared or isolated-- without breaking the code the picture has established for itself and allowing it to slop over into purplish melodrama (like another film I could name). The only thing that keeps me from unreservedly declaring Code Unknown a masterpiece is that it is the first encounter I’ve had with the work of Michael Haneke, and I like to have a little more familiarity, a little more context to drawn upon before bestowing such a judgment. But whether I can declare it a masterpiece or not, it certainly does seem to me the apex of this kind of investigation into the way that people cross amongst each other, how cultures seep into one another, are informed by one another, and how people live and exist and flail and love and create a sense of responsibility, of community, and how some (like Maria) are left out of that picture altogether even as they drift among its signposts. Haneke avoids the kind of haughty disregard for his own characters that crippled Robert Altman’s Short Cuts. (The disastrous decision to excise the Northwest from the stories of Raymond Carver from which Altman stitched his film together, as if to say what was most important about Carver was not his poetry but his plots, did the director no favors either.) And he eschews P.T. Anderson’s penchant for visual overstatement (which I tend not to mind, if it results in a sequence as brilliantly inexplicable and unsettling as Magnolia’s rain of frogs). Haneke can, however, tie an entire disparate bundle of feelings, experiences and implications together with a touch as glancing and moving as the way he ends Code Unknown. A simple shot of a multiracial group of children and adults playing African drums at an outdoor festival, the sound of which carries over and accompanies a kind of visual coda-- Maria, who has returned to Paris, only to find herself homeless and without work again, attempts to land on the same storefront step she was on when we first met her, but is chased off; Anne emerges from the subway and makes her way to the front door of her apartment; her boyfriend, a war photographer, who disappeared without notice to Kabul, reappears, attempts to enter the apartment building but finds the pass code has changed and, upon attempting a phone call, that her phone number has as well; and a final return to a deaf child perhaps interpreting a series of events or other emotions like the ones considered at the beginning of the film, all in body and sign language, for some of us yet another code unknown.

The scene is a brilliant tour de force from Binoche, who creates high point after high point like this throughout the film. In a career full of exceptional performances, this is the very best work I’ve ever seen from her. But it’s Haneke’s triumph as well, as the scene turns out to be the emotional climax of the film, and a more powerful, elliptical way of summing up and addressing the concerns of the entire picture I couldn't imagine— the way the electricity of all these interwoven connections fires on the nerve endings of these characters to create meaning through experience, shared or isolated-- without breaking the code the picture has established for itself and allowing it to slop over into purplish melodrama (like another film I could name). The only thing that keeps me from unreservedly declaring Code Unknown a masterpiece is that it is the first encounter I’ve had with the work of Michael Haneke, and I like to have a little more familiarity, a little more context to drawn upon before bestowing such a judgment. But whether I can declare it a masterpiece or not, it certainly does seem to me the apex of this kind of investigation into the way that people cross amongst each other, how cultures seep into one another, are informed by one another, and how people live and exist and flail and love and create a sense of responsibility, of community, and how some (like Maria) are left out of that picture altogether even as they drift among its signposts. Haneke avoids the kind of haughty disregard for his own characters that crippled Robert Altman’s Short Cuts. (The disastrous decision to excise the Northwest from the stories of Raymond Carver from which Altman stitched his film together, as if to say what was most important about Carver was not his poetry but his plots, did the director no favors either.) And he eschews P.T. Anderson’s penchant for visual overstatement (which I tend not to mind, if it results in a sequence as brilliantly inexplicable and unsettling as Magnolia’s rain of frogs). Haneke can, however, tie an entire disparate bundle of feelings, experiences and implications together with a touch as glancing and moving as the way he ends Code Unknown. A simple shot of a multiracial group of children and adults playing African drums at an outdoor festival, the sound of which carries over and accompanies a kind of visual coda-- Maria, who has returned to Paris, only to find herself homeless and without work again, attempts to land on the same storefront step she was on when we first met her, but is chased off; Anne emerges from the subway and makes her way to the front door of her apartment; her boyfriend, a war photographer, who disappeared without notice to Kabul, reappears, attempts to enter the apartment building but finds the pass code has changed and, upon attempting a phone call, that her phone number has as well; and a final return to a deaf child perhaps interpreting a series of events or other emotions like the ones considered at the beginning of the film, all in body and sign language, for some of us yet another code unknown. *************************************************************************************

The Code Unknown Blog-a-Thon continues with great pieces on the movie available at the following links:

Aaron at Cinephiliac

David at Drifting

Dipanjan at Dipanjan's Random Muses

Eric at When Canses Were Classeled

Filmbrain at Like Anna Karina's Sweater

Flickhead

Girish

Matt at Esoteric Rabbit

Michael at CultureSpace

Michael Guillen at The Evening Class

Zach at Elusive Lucidity

Girish may have a more recently updated list of participating bloggers available on his post, but I will try to keep this list as current as possible.

*************************************************************************************

(A final note: the domestic Kino Video DVD release of Code Unknown may be one of the worst-looking DVDs of a major film I've ever encountered. For a side-by-side comparison of the Kino region 1 disc and the Artificial Eye region 2 disc-- the difference is shocking-- as well as a detailed explanation as to why the Kino disc looks the way it does, visit our friends at DVD Beaver and see for yourself. It's the best argument for purchasing an all-region DVD player-- which I recently did-- I've seen yet.)

Yay on getting a region free DVD player! I've had one for a couple of years now, initially in order to see the British version of Eyes Wide Shut. Check out Nicheflix for some films you might not otherwise have the opportunity to see.

ReplyDeleteGreat, spot-on contrasts with "Crash", Dennis!

ReplyDeleteWhat a ham-fisted, infuriatingly acclaimed film that was. I have many friends who loved it, and I try to slowly change the topic when it comes up, or I'd make an ass of myself with all my sputtering against it.

And I had no idea about the European DVD edition; thank you for the links.

Excellent piece Dennis! I'm happy to see the Crash contrast, which I briefly allude to in my post. (I also couldn't agree more with you about Crash. Awful, awful film!)

ReplyDeleteGood to know about the AE disc. I have the MK2 release from France, and while it is better than the Kino disc, is still pretty sub-par.

That would be awesome if they put out a Special Liberal Guilt Edition DVD of Crash with the pullquote "The exact opposite of A History of Violence!"

ReplyDeleteKa-ching! At 2:32 pm was recorded the best laugh of the day, courtesy of Aaron. Roscoe, do you mind if I send your line to Lion's Gate Home Video? ;) Girish, Filmbrain, Aaron-- I've really enjoyed your posts as well and I hope to get your sites later this evening and say so! Again, another great Blog-a-Thon which has been very eye-opening and challenging for me as a writer, and very beneficial too as a viewer. What's after Abel Ferrara?

ReplyDeletePeter: My first region 2 disc may very well be Code Unknown...

Dennis, I really liked your post, and the important contrasts you draw between Crash and Code Unknown, two films that could not be any further apart on the spectrum in terms of their artistry and what they ask from the audience. Crash is a film of flimsy, uninspired platitudes, all served up like center-field home runs, and its sense of importance is glaringly disproportionate to the bland, uninspired subject at its center. Code Unknown is its polar opposite, working in understated ways to piece together a single, stunning image of modern urban life; I admired it as much for its form as for its uncompromising views.

ReplyDeleteAfter reading your post, I kept thinking about another contrast, that between Binoche (who I agree is phenomenal here, as she always is) and Sandra Bullock. That speech of hers (Bullocks' that is) basically comes off like this: "I. JUST. HAD. A. GUN. POINTED. IN. MY. FACE." Compare that to the brilliant ways Binoche internalizes her experience, therefore making it all the more convincing, accurate, and effective. There are two ways of acting: there's the American way (like being bludgeoned with a hammer) and the more effective one, embodied by Binoche, as well as by actors like Liv Ullman (my favorite performance of Binoche's so far is that in Kieslowski's Blue).

I'm new to Haneke as well. Like you, I don't quite know if it's a masterpiece. I think it fits nicely within a long tradition of European films of alienation, but sort of updates the themes for a more modern, turn-of-the-millennium setting.

By the way, loved your metaphor of the cracked windshield.

Dennis,

ReplyDeleteIt's been several years since I felt obliged to see Oscar nominees I wasn't otherwise interested in seeing, but for some reason, despite a near-certain feeling that I'll despise or at least dislike the film, I keep having these urges to see Crash, especially now that it's being theatrically rereleased in Frisco on Wednesday. This post is yet another argument.

As for Code Unknown, I didn't find time to watch it until this morning and I don't feel I have much to add to the discussion but I was made curious about one thing you said regarding Jean's return to the farm. I didn't take that interpretation at all. For some reason I just assumed that Jean took off for good and that the scenes showing him and his father occured prior to the key second scene of the film. Now you've got me wondering again.

Brian: I think I probably just assumed that he did return simply because he was being offered no long-term alternative by Anne, in terms of a temporary place to stay, and also because the movie's chronology didn't seem to incorporate any other time-shifting up to that point. There certainly isn't any point made as to why he would return one last time, however, so maybe I just missed something. But when he does come back to his father's kitchen, to that bowl full of beets, he has that quality, in his body language and general sullenness, of someone who's last hope has been defeated. (Maybe there's a clue that French-speaking viewers can cull from the note he leaves his father that indicates he's off to stay with Anne and his brother?) I hope to get another look at the movie soon, and I'll keep an eye out for any indications that what we're seeing when Jean is on the farm might have occurred before his encunter with Anne (and Amadou) on that Parisian street.

ReplyDeleteAs for Crash, like you, the days are long gone when I could even hope to see everything that gets an Oscar nomination, along with my insatiable desire to do so. But the DVD release made it irresistible, especially since I had a window this weekend that allowed me to see it and take advantage of what (without having yet seen the movie) seemed like an apt comparison between it and Code Unknown. It's fairly telling that it took me nearly a year to catch up to Crash after its theatrical release-- Hollywood movies that position themselves as big sweeping statements on white-hot social issues usually have to work a little harder to hook me in (and despite its indie credentials, this is a Hollywood movie that Stanley Kramer would have loved). And after seeing it I'm pretty convinced that there's gonna be a big surprise in store for all those folks who put a check next to Brokeback Mountain in the Best Picture slot on their office Oscar pool ballot...

Roscoe: You're WAAAAY too kind! But thanks anyway. And you're right: there's nothing like a good beating with the social commentary stick to convince some viewers they've seen something worth seeing. I'd have to look back at an actual list to be sure, but it seems to me that Crash might be the worst movie to get a Best Picture nomination in a good long while.

ReplyDeleteRe: CRASH winning Best Picture: You think? I reckon you have a better grasp of what the voters will do than I have, but it's hard for me to believe people think enough of that film to propel it to that level. I remember when it was released, it seemed to me that any critic worth listening to, and anyone I knew whose opinion seemed at all worth listening to, was either lukewarm on CRASH or thought it was lousy. On the other hand, with BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, everyone seems either totally enraptured by it, or, like me and some other people I know, thought it was just good--but nonetheless thought-and-conversation-provoking. I just haven't encountered anyone who's really enthusiastic about CRASH, or invigorated by it, and even lousy best-picture winners like FORREST GUMP and BRAVEHEART get people's blood pumping.

ReplyDeleteOkay, Blaaagh, so here’s my not-inside-at-all, hopefully-not-too-cynical theory. I think that the (white) liberal guilt card (Crash) is gonna outweigh the progressive social themes card (Brokeback Mountain, Good Night, and Good Luck) and completely crush the Ethics of Journalism (Capote) and Morality of Political Murder cards (Munich).

ReplyDeleteI think, in much the same way that some might assume that criticism of Crash is a tacit endorsement of hate (“How could you not like this movie? It’s about how we struggle to connect in modern society and how we must learn to tolerate and love our fellow man!”), lots of AMPAS members will see a ballot for Crash as a vote for tolerance in our troubled times. (The best correlative in recent Oscar history would be the swell of support for Gandhi over E.T. or Tootsie in 1982. Votes for Gandhi were rightly interpreted, even at the time, as votes for support of nonviolent resistance-- who's gonna vote against that?-- rather than support for Attenborough's mediocre film. Yet history won out in the end, as it has ever since the first Best Picture winner was announced-- E.T. and Tootsie have endured as popular classics, and no one ever mentions Gandhi as anything other than a seriously bloated film of good intentions and little else.)

There’s no such thing as “the Academy” when it comes to making blanket statements through these awards, but as much as a diverse (but not really as diverse as all that, really) body can be seen to engage in groupthink, I think we’ll see it here. Many of the voters are exactly the kind of moneyed West-siders that Crash’s all-thumbs social commentary appeals to. I’m also afraid that these enlightened Academy members will find the movie’s nonreinforcement reinforcement of stereotypes (hostile, aggressive Asians, articulate black car thieves, saintly Mexican housemaids, and not a single citizen of the city with anything on his or her mind other than this race elephant in the corner of the room), coupled with its assumption of the worst about people’s motives, only so its viewers can congratulate themselves on detecting that transparency in the characters and cluck their tongues at it (“I’m so glad I’m not like that, nor is anyone I know!”), pretty irresistible.

Thanks to the Academy’s rules about nondivergence of actual vote tallies, we’ll never know just how many votes Crash, win or lose, will get, but the possibility that many of those votes might be cast by people who see the film on DVD screeners, not wanting to get out of their houses and engage in the reality of a screening room, let alone a multiplex, would, I’d guess, be pretty telling in its own way.

Maybe I’m being too cynical here—the movie has been out since last May, and it’s the biggest grosser of all the nominees so far, Brokeback not yet having played out its theatrical run, so maybe screeners played less of a part here than I’m assuming. But I just can’t help feeling that Crash’s ungainly, unsubtle presentation of its themes will hit closer to home—and maybe only because it plays out in Los Angeles—than the other films do. It’s just a hunch, a theory, and God knows I’ve got as many or more of those with my name on 'em charred and crushed on the sidelines of Oscar Nights past than just about anybody. But that’s the shaky limb I’m gonna perch on this year. I just hope Ennis and Jack, or even better, William R. and Fred, or perhaps even Avner and Golda, are there to catch me if I fall.

Well, you can all scoff at me if you wish, but when I finally saw CRASH, I was really ready to hate it--but instead I thought it was an interesting experiment, a grim cartoon in which all the characters are caricatures in deliberately non-realistic situations. I won't say I loved it, but it didn't feel like a totally cynical piece, and I didn't feel like I was being told that we're all basically seething with hate and resentment toward the "other," and we just have to face it-- which is what I expected to encounter with the film. I am curious to see it again at some point, in light of this discussion.

ReplyDeleteThat said, your argument for it winning the best picture Oscar is pretty damned good--though I hope it doesn't! (Why does this continue to matter to me?!) You're usually right about these things, too. I really enjoyed this post about CRASH, by the way, and now I've gotta see CODE UNKNOWN so I'll know what you're talking about. (I planned to anyway, as I'm a big fan of Juliette B.). I especially like how you begin your piece, with the anecdote about your most recent cross-cultural moment; this is so true to the vast majority of my daily dealings with people from many cultures here at City College of SF: they're usually more interesting--even enlightening--than problematic. This, of course, makes the idea that we're all seething with hate for "the other" seem kind of silly to me; then again, I'm white and a liberal, and I like being in a racially/culturally mixed environment, so what the hell do I know? I'm sure I must be filled with white liberal guilt, and am just fooling myself not to acknowledge it.

Dennis, you've got a great point about how much CRASH has grossed. I never would have thought it would take Best Picture, but the movie most people have actually seen ($) is the one that often wins.

ReplyDeleteGreat reviews on both films. I watched CODE UNKNOWN on Sunday, but as yet another Haneke neophyte, I decided to sit out the blog-a-thon and be enlightened by the rest of you, and you have done that. (I'll be there will bells on for my man, Abel, though.) As for CRASH, I read the script, but I have avoided watching it, both because I expect not to like it (your trustworthy commentary has only encouraged this opinion), and because I'd rather avoid explaining to those who love it that not liking it doesn't make me a white supremicist.

On the subject of racism, do you have any thoughts on George Stevens? He deals with the issue a lot, but I have mixed feelings about him, though I think he has good intentions. I wouldn't mind one of his movies being the subject of a blog-a-thon.

Oh, Dennis. Don't you too fall into that section of people who believe Crash was just some heavy-handed lesson on racism being shoved down their throats. Sure, some of it was a little far-fetched, but some of the scenes you are referring to might be misjudged. Case in point, the scene where Terrence Howard gets out of the car after being chased by the cops. You said the cops want to get him because he's black. If you make the cops chase you, they are going to react this way to most people. Is is possible you had already made up your mind about the movie early on and can't get past that notion of sheer racism?

ReplyDeleteSure, there is that "racism" issue, but I saw the movie more about people having to be broken in one way or another to go on with their life, either good or bad. And sure, these people "crash" into each other in some pretty outrageous circumstances, but to see it how you see it at this point makes me believe you're walking away with tunnel vision rather than an open mind.

And how can you hate any movie with Tony Danza in it is beyond me.

Blaaagh, did you know that the initials SLatIFR also stand for, "Scoffing: Leave It at the Front (door), Rotters!" (Okay, that was a cheat, but I agonized enough over it and couldn't come up with anything better!)

ReplyDeleteAs bad as I think it is, I don't think Crash is a cynical movie either. Quite the opposite. I think Paul Haggis's movie comes from a sincere attempt to engage in issues he thinks are important and, obviously, all-consuming. I'm just taking issue with the ways in which he chooses to dramatize them. And I think the movie's sidestepping of "realism" in order to place its characters in coincidental narrative situations designed to drive home Haggis's points would hold more water if the film weren't, in every other way, so insistent upon be taken so literally in terms of gritty (and sometimes not so gritty), recognizable real life. Here's where the stylish flourishes of a Paul Thomas Anderson might help clarify matters, or maybe muddy them to the point where a less-convinced viewer could at least be helped over the troublesome patches. But it seems to me, at least in this instance, you can't have your fanciful parable cake and eat it on the platter of urban realism too. And on any level, I think the script is just too simplistic for the incredibly complicated subject it's trying to depict.

That said, you're gonna love Juliette Binoche in Code Unknown. And Ryan's Daughter is on it's way from Netflix. Hey! Maybe that's a good call for a future Blog-a-Thon-- is David Lean's most disrespected movie really deserving of the scorn with which it's been held for 36 years?

Cruzbomb: The thing I objected to about that scene in particular wasn't the specter of racial profiling, as if I don't believe such a thing happens. What I objected to was exactly what you said-- the cops chased him down not because he was black, but because he appeared to be running away from them, and they don't follow through with what would really happen in that situation just so the director can score another point on his blackboard.

ReplyDeleteWhen the officers see that he is black, however, they don't get relaxed-- you can see on their faces it's another playing out of a very familiar situation and they expect the worst, and the movie counts on you rifling through your stored-away images of Rodney King and other minorities who have felt the taser and the gun butt and the chokehold of the LAPD. It's a very real situation, not one just confined to Los Angeles, but it gets a very bizarre Hollywood-ized spin at the end. By the time Ryan Phillippe has convinced the officers that, hey, I've seen this guy before and he's okay-- we can let him off with a warning (there's some realism for ya)-- the scene starts to become increasingly bizarre.

Phillippe, being the cop were meant to identify with, makes some pretty big assumptions about Howard based on his one previous experience with the man at the hands of Officer Dillon (perhaps becuase earlier he seeemed to be a pretty wealthy man). It's the movie that has set up the scene to make it come off more as a matter of race, but it's really about the character's refusal to explain his apparently criminal behavior-- he is now a black man, not just a man, who has to stand up to the Man on his own terms rather than take the easy way out and place the blame where it belongs. Why it's considered more honorable to allow the sympathetic white cop to cajole his fellow officers into an incredibly unlikely release rather that calmly explain about his passenger is beyond me.

Howard chooses not to do what I'd wager anyone, black or white, in a similar situation would do-- inform the police, who are pointing weapons at him, that he's been carjacked and that the man responsible for his apparent behavior is hiding in the front seat. The fact that he doesn't do so, it seems the movie is telling us, is because after his experience with the LAPD, he'd rather protect a criminal, based on that criminal's race (both are African-American), rather than help the police (a fraternity which includes Officer Dillon) apprehend a man who prides himself on making sure his crimes are perpetrated (in all other instances but this one) on anyone but a black man. Maybe that's a believable reaction. And maybe the LAPD let reckless drivers drive away from a chase and a weapons-drawn situation all the time. If not, Crash is asking me to swallow an awful lot to further my understanding of its view of racial politics and reality.

I completely understand your point of view about the movie too, about it also being about people having to be broken in one way or another in order to go one with their lives. (That's a theme that a lot of directors have dealt with, but it's also not gonna fire up people's emotions and get free press on the Op-Ed pages and lots of Oscar nominations either.) I think, in a lot of ways, that broken-lives theme is what Magnolia could be said to be about. But in Crash I think the writer-director failed to find a way to adequately dramatize that idea, along with his other ideas about the state of race in America, in Los Angeles. I honestly felt like I was being roughed up and force-fed a message, a message with which I don't largely disagree. (I do take issue with the way the man spins a metaphor, though-- crash, crash, crash.) It's all about the delivery, I guess. I know a lot of people (Blaaagh?) who felt equally bullied by P.T. Anderson's go-for-broke technique in Magnolia.

By the way, is Going Ape! out on DVD yet? 'Cause my VHS copy is just shot to hell.

And stop lurking, why don't ya?! :) I'm glad to see you back in the comments pages. You're keeping me honest, or at the very least less complacent!

NB: Strangely enough, my wife just sent this article to me via the AP wire: "Crash May Pull Off Surprise Oscar Win". I haven't read it yet, but it does seem like it might be germaine (and maybe even German) to the conversation.

ReplyDeleteMy familiarity with George Stevens is limited to Giant, A Place in the Sun and (gulp) The Greatest Story Ever Told. Something's nagging at me that I might be forgetting about seeing one of his older films (Did he direct Stage Door? If so, then there's another one...) I'll add Stevens to my list, that's for sure!

Haha...I just clicked on the link to the article, and saw the author's name (Germain). Did you make that joke intentionally about

ReplyDelete"germaine" and "German", or was it an incredible coincidence, just like the ones in CRASH?!

About the AP article, that reminds me: as soon as CRASH won that SAG award for entire cast performance, or whatever it is, I started seeing stuff about how all of a sudden it looked like CRASH might win the Oscar...but aren't the SAG awards specifically acting awards? I didn't think it sounded like an equivalent category...

Holy schnike! I was just making what I thought was a meaningless joke! I swear, I did not notice that or intend it. Whoa! I feel like I just got touched by a ghost from the other side or something! Haha! I take it all back! Coincidences, coschmincidences! Crash for Best Picture and Best Screenplay!

ReplyDeleteI think the thing they're spouting about regarding the SAG awards was that Brokeback Mountain got upset there. Eveyone expected it would roll through the SAG awards, and I think it ended up with nothing. I don't think they were suggesting that the voting block was entirely comparable. Although actors do form the biggest branch on the AMPAS tree...

ReplyDeleteNB: Whoops! Stage Door was Gregory La Cava (I should never step out without consulting IMDb or my 2006 Leonard Maltin). But in looking up Stevens I'm embarrassed to admit I forgot completely about Swing Time, Gunga Din, Penny Serenade and The Diary of Anne Frank. But the one I was scratching around for in the dark recesses of my head was The More The Merrier, an absolutely terrific screwball comedy with Joel McCrea, Jean Arthur and Charles Coburn. Off to Netflix I go!

ReplyDeleteWow, this set of comments has really taken off! I was sheepish to admit I thought CRASH was not bad, but now I'm glad I did, as for once I didn't kill the momentum of the comments, as I often seem to. Thom, you kill me with your jibes to Cruzbomb (who, by the way, I'm glad to hear from!). And oddly enough, Thom, I've gone through years when the Oscars came on and I'd seen only one of the best-picture nominees, and somehow I not only survived but realized I'd had a pretty good year!

ReplyDeleteUlp...now I have killed the discussion again. Oh, well...I'll be curious to see what you think of RYAN'S DAUGHTER now, and I like your idea of a blog-a-thon about it. I know it can't be as bad as it's been made out to be, and probably not as good as I always thought it was, having seen it as a young kid. But I watched the first half the other night, and I think--oh never mind, I'll save it for the blog-a-thon, if it ever happens.

ReplyDeleteRegarding Ryan's Daughter, Dave Kehr, who writes DVD reviews for the New York Times said it was "simply one of the most spectacular video presentations I have ever encountered, a marvel of pinpoint resolution and stable, saturated color...." I believe he also said something about it being so good as to make to believe you were watching HDTV. Wow! I wish I could give you a link to the whole review, but it's one of those things that you have to buy a subscription to the NYT in order to see. But I think we get the idea that Dave was very impressed with the DVD.

ReplyDeleteRyan's Daughter definitely fills the blog-a-thon bill, though, and, strangely enough, in some of the same ways Showgirls did-- a critically dismissed film (though Ryan's Daughter was a much bigger box-office draw than Showgirls was) that might be very interesting to look at from 36 years down the road. I can't wait to see it again myself, although when I added it to my Netflix queue, it "saved" it for me-- in other words, put it on the list of titles that have not yet been released. Hmm.

Oh, and you're by no means a comments killer. Sometimes you're the ONLY one who comments! I was kind of surprised how the comments yesterday snowballed too, and it may explain why I was up until 3:30 this morning doing the work I should have been doing yesterday afternoon instead of having fun here instead!

Wow, that's impressive what Mr. Kehr (hee hee, just following the New York Times stylebook) says about the DVD! I agree: it looks stunning. And I will say, in advance of the blog-a-thon, that I still think it's quite a good movie; the things that seem awkward or labored to me are pretty much typical of Lean's style or sensibility. There are also some very fine performances: in particular this time I'm enjoying Trevor Howard. It's interesting to look at the acting again as an adult. I could go on about the visuals, the sound, etc., but I'll wait'll you see it so I can argue with you!

ReplyDeleteDennis, as a matter of fact, I had this friend who was a little on the wild side. Well, one night he ran from the police in his car with two passengers, I being one of them. I finally convinced him to pull over and the cops were on us, guns drawn. We were made to leave the car running and place our hands on the hood of the car, which was getting quite hot. After an hour of this and their verbal abuse, they let us go, with a warning. Things like this do happen, thank God.

ReplyDeleteAs for us reaching back into that Rodney King memory with the cops seems to me to be quite a stretch. As everyone wanted to believe that incident was strictly race-related, I recall another incident a couple of years before that of two cops brutally beating a young Caucasian boy of 20, and it was all caught on tape and shown on the news later that night. The young boy was clearly not resisting arrest, as he was kneeling on the ground with his hands on his head while he was beaten, just like Mr. King was a couple of years later. How do I remember this incident? I was standing next to the cameraman at that party.

You're saying these situations were too much to swallow in the movie. I felt they were had quite a touch of realism to them.

But I'd have to agree with that Thom McGregor dude. Your writing throughout this whole piece was like poetry. As much as I don't agree with some of the views, I couldn't stop myself from reading them.

Kiss, kiss, good night.

Cruzbomb: Your personal observations and experiences here are invaluable to me, and I really appreciate your taking the time to relate them and challenge my perceptions of the movie. I just think Haggis undermines Crash's effectiveness by sapping the nuance from his stories and his characters so all that I was left with to concentrate on was the apparent improbability of the situations. Even though you've been witness to similar scenes, the way they're depicted in Crash, and the uses to which they are put, still feel false to me within the context of the movie. I'd wager that if anyone who had been through what you'd been through had written those scenes, rather than a Hollywood writer spinning predicaments from the safety of his den based on his own fears after being carjacked, they might have have some of the believable detail and ambiguity, the signposts of truth, that I find missing from Crash.

ReplyDeleteAnd thanks for your words of support. I've often found that my favorite writers on film are ones whose opinions provoke and madden me as often as they illuminate my perspective on any given movie (sometimes they do both at the same time.) So I really appreciate that you were compelled to read on even as you were arguing back.

Did you find out about Going Ape for me? 'Cause my tape is useless, and I'm really feeling the need for a little of that magic that only DeVito and Danza can provide...

Dennis, thank you for writing about CODE UNKNOWN. Ever since I saw BLEU, I've been a big Binoche fan. For some mysterious reason, in 2000, I managed to see CHOCOLAT [ Raspberry ] but missed CODE UNKNOWN, and I'd forgotten to nab it on DVD until now.

ReplyDeleteIt was good, solid fun - I had that rare pleasure of watching it without any expectations about the plot or structure or style. (I stopped reading your essay at the conclusion of the brilliant review of CRASH and returned to it only afterward.) I loved Anne's movie scenes, and I was totally taken in by the creepiness of what was later revealed to be her audition. Do you remember the theatrical trailer at all? I think I remember seeing a preview at the Nuart maybe that featured Anne and her thriller costar cracking up in the dubbing studio, much different from the trailer included on the region 1 DVD. Anyway, a beautirific scene that probably lit my fire for this movie in the first place.

Both Metro scenes (the one you describe so well and then Georges with his camera) were extremely uncomfortable for me (I've got a weird hang-up about seeing public transit portrayed negatively) but ultimately satisfying (huge release when Anne bursts out in tears and thanks her fellow passenger and strange relief when we see the beautiful portraits resulting from Georges's creep-fest).

Yea! I've ordered THE PIANO TEACHER from the library, and I'm hoping CACHE will come to the Darkside soon. And I promise to make my way over to your fellow blog-a-thoners' essays too.

Nay! however, to PTA and his stoopid rain of frogs. Sorry, Dennis! I wish I could articulate why I loathe MAGNOLIA so.

blaagh worries about killing the momentum of the comments; I show up when the party's over!

And one last note to Thom: Thom, when I first heard some folks discussing CRASH a few months ago, I obviously assumed they meant the Cronenberg version! I would be honored to take you out to see your choice of the Best Picture nominees, you know. I haven't seen any of them either!