(NOTE: This is part two of my personal retrospective on the films of Robert Altman, in honor of the director's 81st birthday and his upcoming honorary Oscar, to be presented during the telecast of the Academy Awards on March 5. You can access part 1 of this article by scrolling down this page or by clicking

here.)

***********************************************************************

Before we get revved up again, I'd like to pass along a couple of other items recommended for further research that are appropriate for this stage of the game.

First, there's a detailed and engrossing article over at

24 Lies at Second by Robert Cumbow entitled

"Altman and Coppola in the '70s: Power to the People" which looks at perhaps the two most emblematic figures in what has become widely thought of as the last great creative period of American filmmaking.

Anyone interested in Altman's biography, his working methods and detailed history of the production of his films have a couple of good sources available-- Patrick McGilligan's warts-and-all portrait

Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff and Jan Stuart's detailed look at the making of the director's most acclaimed film,

The Nashville Chronicles: The Making of Robert Altman's Masterpiece.

A worthwhile critical appraisal of the director's work can be found in Robert Self's book

Robert Altman's Subliminal Reality. And David Sterritt offers

Robert Altman: Interviews as part of his "Conversations with Filmmakers" series. And the BBC Four offers some brief

audio clips of interviews that are worth a quick listen. For that matter, Altman is one of the few modern directors of stature (Scorsese is probably the only other one) who has produced consistently worthwhile audio commentaries on many of the DVDs of his films, and they are perhaps the best source of information film-to-film to be obtained directly from the filmmaker. Some of the best include track on the DVD releases of

Nashville, Dr. T and the Women, Short Cuts, Secret Honor, California Split and, if you can find them, the laserdisc editions of

The Player and

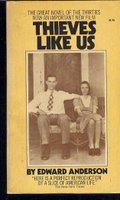

Thieves Like Us.

And perhaps most impressive is

Ray Sawhill's perceptive reconsideration of

Nashville, published in Salon in 2000, on the occasion of the movie's 25th anniversary and its first release on DVD.

************************************************************************

Finally, Matt Zoller Seitz has thrown down the gauntlet and proposed an

Altman Weekend Blog-a-Thon to coincide with the director's career honor at the Academy Awards the weekend after next. Bloggers who are interested in participating will write about any film or other fascinating aspect of the director's career and post on Friday, March 3 or since, as Matt says, "the Altman spirit demands keeping things loose," anytime over the weekend before the Academy Awards ceremony will do. This should be a lot of fun, both to write and to collect up and read in the afterglow of the Oscars. Reading all the individual, idiosyncratic takes on this great director's career should do wonders toward offsetting any bad taste left in the mouth by upsetting upsets, embarrassing exhibitions on the part of out-of-control winners, or, perhaps, a not-so-shining performance of your own in the office Oscar pool. Remember, next weekend isn't Oscar Weekend, it's

Altman Weekend-- get ready for it.

(And in the all-inclusive, democratic community spirit of the director's films, anyone who is without a blog of their own but would like to contribute a piece to the Altman Weekend Blog-a-Thon is more than welcome to submit their pieces to me via e-mail for publication alongside my own article next Friday, March 3. I encourage your submissions and look forward to reading them, along with everyone else's, next weekend.)

************************************************************************

Robert Altman hit a career high in terms of the critical reception of

Nashville. Of course neither his admirers, his collaborators nor he himself would have any idea this was the case as it was happening, nor would any of them have any way of knowing that the director was about to embark on the phase of his career that most would term as his most creatively trying and challenging. Indeed, Altman proceeded along his career path taking each obstacle as it came, not seeming to care much about his vexed box-office record or betraying much worry about creative methods and inspiration. The way most of Altman's films feel, particularly those of the period from 1976 through the mid '90s, seem to be pretty much the way they were conceived and executed-- still in a very loose, intuitive, collaborative manner, yet with an increasing sense of being hermetically sealed off from the industry wihin which they circulated, and with decreasing concern for connecting with a mass audience. By the first few months of 1980, he had, for all intents and purposes, given up that pursuit altogether.

BUFFALO BILL AND THE INDIANS, or SITTING BULL'S HISTORY LESSON

BUFFALO BILL AND THE INDIANS, or SITTING BULL'S HISTORY LESSON (1976) In the wake of my disastrous initiation into the world of Robert Altman at that screening of

Nashville in 1975, let's just say I wasn't the ideal audience for the director's follow-up feature. Yet, because my hometown theater, the Alger, booked it, probably figuring it might hold some appeal to local viewers who still held westerns in high regard (and boy, would those unsuspecting folks have had a surprise coming to them if they took the bait), and because there would be no other movie in town for a whole week, there I was, on opening night of the movie's five-day engagement, bored to frustration. Yet even then I recognized a kernel of what Altman was up to right from the get-go--

Buffalo Bill featured the most elaborate example yet of one of Altman's signature moments, the self-consciously attention-grabbing opening credit sequence that announced the movie

as a movie and at the same time hinted at the film's ultimate inquiry into the tissue of lies that compose the entertainer's (and the filmmaker's) bag of tricks, and by extension (through Buffalo Bill's interactions with Sitting Bull) those of a certain manifest destiny-inclined world power celebrating its bicentennial in the year the film came out. It took me another 10 years to revisit the movie and realize I hadn't given it anywhere near a fair shake. And in the years since it's initial release its reputation hasn't grown much, even within the community of Altman devotees, beyond its status as a signifier of expectations raised by the triumph of

Nashville that ultimately went unfulfilled. But the movie has expanded in my mind much further beyond that narrow perception, and as I think about it now I realize that it is the movie I'm gravitating toward as the Altman Weekend Blog-a-Thon draws ever nearer. Stay tuned. (By the way, the

Buffalo Bill one sheet pictured is my favorite from all Altman's films, and one of the few one-sheets that I actually own-- I procured it from that Alger Theater run in 1976.)

3 WOMEN

3 WOMEN (1977) If

Thieves Like Us planted the suspicion that Shelley Duvall might just be my favorite actress, Altman's insinuatingly sinister, gossamer dreamscape confirmed it. Altman tended to feature Duvall in roles that required her to expose herself to an uncomfortable degree through harsh or sometimes inexplicable behavior, and her Millie Lamoreaux here is initially likable but increasingly, insistently pathetic, a performance of real daring in terms of flirting with creating a character cut so close to the bone as to be painful, one who tears the audience between wanting to see Duvall at work and wanting to turn away from the agonizing level to which the actress lays herself bare. And that she creates such a realistic, nuanced performance within Altman's diaphanously realized and haunted canvas of splintered personality dream logic is perhaps the ultimate testament to her achievement here.

3 Women

3 Women (the other two are Sissy Spacek, as Millie's roommate Pinky, and Janice Rule as a mysterious, pregnant woman who paints eerie murals on the bottom of a swimming pool) finds Altman dabbling again in the psychological gamesmanship of

Images, but this time he's unmoored himself from the reliance on literal symbolism-- the images invoked and inspired by the titular females' shifting, interchanging personalities are slippery, intangible, frighteningly suggestive yet elusive. However, you never get the sense that Altman is playing the "whatever-you-think-it-means-is-what-it-means" shell game. In fact, you can sense the director himself trying to grapple with the implications of the imagery he's processed here (some of which, according to legend, originated in one of Altman's own dreams).

A WEDDING

A WEDDING (1978) Or, 48 Outlines of Characters In Search of a Movie.

A Wedding finds Altman self-consciously revisiting the narrative strategy of

Nashville (which itself was an expansion upon the groundwork initially laid in

Brewster McCloud, a film that could just as easily have been called

Houston) and upping the ante, doubling the amount of balls he attempts to juggle. The scenario (the reception following the Chicago society wedding between corrupt old money and the grotesquely nouveau riche) would seem to justify the experiment, and the movie's on-the-fly construction is admirable. But it's a movie seriously leached of the element of high spirits that helped keep

Nashville soaring. Instead,

A Wedding skirts a joyless diagrammatic approach that finds time for the humiliating of almost every one of its 48 "characters" (they seem to me more like nicely dressed chess pieces on a board seriously near being upended) in the name of bitterly funny social observation. Where

Nashville was breezy yet down-to-earth, intricate yet liberating and free-associative,

A Wedding just seem overstuffed and overly determinate. Even so, there are wonderful performances, which seemed even better when I revisited the movie late last year-- I treasure the unmoored cadences of Nina Van Pallandt's drug-addicted mother of the groom, especially after she gets high and the actress's normally muted, unactressy line readings really take off to Slurrrrsssvillle; and Vittorio Gassman, as the father of the groom, who has lived a life of indentured servitude to the racist family matriarch ever since his own wedding and who, upon discovery of the matriarch's death, suddenly finds himself free-- his reunion with a long-lost brother, whose presence he fears will violate the terms of his servitude (before he has realized he's no longer bound) is a hilarious comic explosion of anger and flustered reconciliation; and, of course, Lillian Gish as the matriarch, who opens the film, speaks briefly, then promptly dies, but whose poisonous spirit hangs over the entire proceeding (for good and bad, I think)-- Altman honors Gish in the way he frames her character in a window at the onset, the then still-living patron saint of the history of cinema, but he never finds a way to honor her through the processional of his own film.

QUINTET

QUINTET (1979) If you would have asked me two years ago what film of Robert Altman's I held in least regard, I would have said

Quintet, which remains the nadir of Altman's puzzle-picture trilogy (

Images and

3 Women being the other, more successful pieces). It's a suffocatingly lugubrious chunk of heavy-handed sci-fi allegory set in a frozen future wasteland and built on the characters' all-consuming obsession with a backgammon-like game, played to the death and overseen by the phonetically maddening Fernando Rey, the rules of which remain as mysterious to us at the end of the film as they were when it started. But the defiantly esoteric, visually irritating

Quintet (the entire film, already rather fuzzily rendered by cinematographer Jean Boffety, is decorated with a Vaseline smudge around the edges of the frame) has been supplanted at the bottom of the barrel-- the actual bearer of Least Regarded Altman Film in my estimation may come as a surprise to some, as it is generally thought of as a brilliant piece of work, and I will leave it to be revealed at the appropriate time. The movie's humorless pretense is in no way redeemed, but it is leavened somewhat by an unintentionally hilarious scene between Rey, Bibi Andersson and Vittorio Gassman (who here burns through the good will he generated in

A Wedding) in which they debate the fatal implications of the game. Gassman and Andersson are seated on either side of the freshly killed corpse of Nina Van Pallandt, who stares lifelessly ahead with a spike sticking through her head while these European stars gnaw hopelessly on the clunky English dialogue supplied by Frank Barhydt and their director. Meanwhile, star Paul Newman presides over the film with appropriate dourness, a blue-eyed deer caught in the headlights.

SLIFR reader

That Little Round-Headed Boy asked me recently if there was an Altman film that I found too unbearable to sit all the way through. My answer was no, I've never walked out on an Altman film. But I can remember the cold and rainy Sunday afternoon when Blaaagh and I sat in a cavernous (and empty) movie palace in downtown Eugene and endured

Quintet for the first time. I know both of us wanted to bolt, but we stayed to the bitter (and I do mean bitter) end.

A PERFECT COUPLE

A PERFECT COUPLE (1979) I remember very little of this light, somewhat odd romantic comedy starring Paul Dooley and Marta Heflin, apart from it being structured around the performances of a rock band with a rather overwrought name (something in the neighborhood of Takin' It to the Streets) whose front man was none other than Ted "Jesus Christ" Neeley. But the opportunity to revisit it again is on the immediate horizon-- it's being released in DVD box package with

Quintet,

M*A*S*H,

A Wedding (all of which, by the way, bear the stamp of the subtitles and closed-captions created by myself and

SLIFR readers Thom McGregor and the Mysterious Adrian Betamax). And if you're feeling adventurous, you could venture to win that box set by visiting Aaron at

Cinephiliac and keeping your

"Eyes on the Prize". (Be warned, though: you'll be in direct competition with me, and as of week #1 anyway I'm doing pretty well.) An interesting bit of

A Perfect Couple trivia courtesy of IMDb: the role of Sheila Shea was originally written for Sandy Dennis. But Dooley was seriously allergic to cats, and cat-lover Dennis would come to the script readings with up to five cats in tow, causing Dooley at one point to be hospitalized. As a result, screenwriter Allan Nichols refashioned the role from an earth mother type to the young singer/groupie played eventually played by Heflin.

H*E*A*L*T*H

H*E*A*L*T*H (1980) Altman again revisits the cacophonous, multi-character canvas of

Nashville (and, rather too strenuously and self-consciously, the acronymic nomenclature of

M*A*S*H) for this bizarre comedy centered around a political battle staged during a convention of health food entrepreneurs. The effectiveness (or lack thereof) of its attempt to engage in irreverent political allegory on the eve of the Reagan era was pretty much lost, either through the movie's torturously delayed premiere (it was basically dumped by 20th Century Fox as unreleaseable, which added somewhat to its briefly enjoyed reputation as a buried treasure) or its own overly tangled narrative web. The movie mixes high and low comedy in a distinctly Altmanesque style that is very reminiscent of the similarly messy (and, I think, underrated)

Pret-a-Porter, and as a result it is the very essence of "hit-and-miss," but it's also one I've longed to return to for quite a while. Fox Movie Channel trots it out occasionally; unfortunately, the print shown there (at least when it showed up last month) was irritatingly cropped and derived from a less-than-satisfactory transfer, so I opted out in the hopes that the current mining of Altman's late '70s Fox period would result in a DVD somewhere in the near future. Whatever the circumstances under which I next see

H*E*A*L*T*H, I can be sure they will not resemble those of my first encounter with this orphaned Altman oddity. In 1981, fresh out of college, where I spent a third of my senior year immersed in the Altman canon, I drove seven hours from my hometown in Southern Oregon to meet Blaaagh in Portland, where

H*E*A*L*T*H was playing an exclusive limited engagement at the

Cinema 21 theater. Ah, the unfettered enthusiasm of youth!

POPEYE

POPEYE (1980) The experience of making this movie, under the aegis of producer/bully/bullshit artist extraordinaire Robert Evans, and its ultimate lukewarm reception (with the attendant unearned reputation as a artistic and financial bomb) would finally drive Altman, the iconoclast's iconoclast, from the prescribed madness of Hollywood conservatism and into the wilderness of independent filmmaking as it existed in the days when John Sayles was still fresh off of

Return of the Seacaucus Seven and the world had not yet heard of Jim Jarmusch or Spike Lee. Few had the desire, when

Popeye was released during Christmas 1980, to look at it apart from the stories generated from its troubled production with anything resembling objectivity (or better yet, intelligent subjectivity). And it has yet to be revisited and reassessed in any satisfying way (which makes me look forward even more to That Little Round-Headed Boy's Altman Weekend

Blog-a-Thon entry on it next week).

For me,

Popeye was and is a marvel of set design and pioneering use of cinematography--I always drift back in my mind to that seaside Maltese village where the characters of the movie live, flattened so expressively by the long lenses of

Giuseppe Rotunno's camera into the first real attempts to emulate a cartoon universe in three dimensions. And again, my unabashed awe for the unpretentious talent of Shelley Duvall continued here-- if anyone was ever born to align with a particular cartoon character, it was Duvall and her embodiment of Olive Oyl in a performance that I genuinely felt deserved the Oscar that year (she even outdid her own supremely empathetic work in

The Shining from that past summer). But Altman's sensibility was also well suited to the material, despite the insistence of everyone from Evans to the emerging magpie reporting of fledging infotainment shows like

Entertainment Tonight that he and

Popeye were a strange mismatch (they certainly fit better than Ang Lee and the Incredible Hulk). Altman's propensity for the function of community, in the way he builds the inside of his Panavision frame, and in the generous way he approaches the relentless presence of the multitude of characters (including Williams as the titular sailor and the endearing manner in which he mutters his way through the movie) expands

Popeye beyond the limited perspective of the typical blockbuster, and that's probably one of the things that got it in trouble with critics and with audiences. For the next 12 years (in what could only in retrospect be anything more than a coincidence, approximately the length of the Reagan-Bush era) Altman would find himself frozen out of the Hollywood that he so openly eschewed, the formula-driven, blockbuster-addicted system that now openly acknowledged that it had no idea what to do with this one-of-a-kind artist. It would be a journey that would return Altman to the fundamentals of filmmaking (filtered, of course, through his own unique sensibility) and ultimately set the stage for this iconoclast's second run at the Hollywood establishment.

Next: Altman in the dark forest of the '80s, and his (brief) return to Hollywood glory in the '90s.