Sergio Leone seemed destined to live a life in the movies. The son of Italian silent film pioneer Vincenzo Leone and actress Bice Waleran, he apprenticed in film production in his late 20s, rising through the ranks until he finally landed some screenwriting work and a series of high-profile second-unit directing jobs on such films as Vittorio de Sica's The Bicycle Thief (1948), Mervyn LeRoy's Quo Vadis? (1951), Fred Zinneman's The Nun's Story (1959) and William Wyler's Ben-Hur (1959). He took over directing the Steve Reeves sword-and-sandal epic The Last Days of Pompei (1959) after original director Mario Bonnard fell ill, though he was left uncredited on the finished film. Dues paid, he finally made his official debut as a director with The Colossus of Rhodes (1960), starring a miscast and uncomfortable-looking Rory Calhoun, and followed with another second unit job on Robert Aldrich's Sodom and Gomorrah.

It might have seemed to the casual observer (and there probably was no other observer of Leone's career in 1962 that could be described as anything other than casual) that he was lining up to become a footnote in film history as a solid, if none-too-distinct director of the kind of biblical/historical epics that had already peaked in popularity. Those epics would give way, as would big-budget formula pictures such as the musical and, significantly, the western, to the influences of the French new wave that would help to virtually dismantle the Hollywood studio system and produce audacious, revolutionary and reflective films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch. But instead of shuffling off into a career of comfortable craftsmanship and relative obscurity, Leone decided that, for his sophomore directorial effort, he would see if anyone noticed while he shamelessly ripped off Akira Kurosawa and his 1961 film Yojimbo (whose own roots were tangled up with Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest and perhaps even an 18th-century farce entitled A Servant and Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni).

Leone imagined casting Henry Fonda, James Coburn (who once claimed Leone’s script was the worst he’d ever read), Coburn’s Magnificent Seven and Great Escape costar Charles Bronson, and even Calhoun, in the lead role of a drifter gunman, never identified by name, who plays two warring families against each other in a dusty town located near the Texas-Mexican border. But none of the Hollywood veterans were either available or could be convinced to come to Italy for what Leone was willing to pay. Instead, Leone reluctantly hired a TV cowboy named Clint Eastwood, who was on vacation from his American series Rawhide and who figured that, though making the movie was a good way to spend his off time learning about filmmaking, no one would ever see it. The movie was not the first instance of what would come to be known as the spaghetti western, but Leone’s Yojimbo riff, titled A Fistful of Dollars (1964), was the first of the Italian westerns to become an international hit.

Dollars wasn't released in the United States until 1967. In the meantime, Leone had coaxed Eastwood back for a sequel, For a Few Dollars More (1965), and the capper of what would become known as the Dollars Trilogy, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). When the first two Dollars films became unqualified hits in the States, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was already waiting in the wings, and by the time it finally saw the light of American projectors in 1968, the Eastwood/Leone phenomenon was at full throttle.

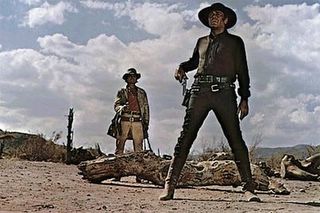

These violent, amoral fables were spun from the contrast between Leone’s operatic, mercilessly astringent, self-conscious style and the morally ambiguous calm of Eastwood’s Man with No Name, who erupts into unexpected action as suddenly as Leone might swing the visual pendulum from a deep-focus long view of a stark, empty plain to a startling, Techniscope frame-filling close-up of a glowering, weather-beaten thug in the same shot. And their caustic reconsideration and recasting of the myths and behavioral codes of the Western coincided with the fast fading at the box office of that most American of film genres in the very country of its origin, as well as the reconsideration of many societal roles and assumptions by the younger generation that was just coming of age and becoming aware of the artistic possibilities of film.

During this period (1962-1974), the films of Sam Peckinpah (Ride the High Country, Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) and Robert Aldrich (Ulzana’s Raid) were probably the most telling of the American westerns, in terms of the tension between the times they depicted, the times in which they were made (and how the tensions of those differing times frequently overlapped), as well as their directors’ fevered ambitions and demons as artists. But the Italian Leone brought a revisionist daydreamer's sense of spectacle, and a delirium-spiked nihilism, to his westerns that was far more harsh and critical of American mythology than even Peckinpah at his most agonized and circumspect (The Wild Bunch) or Aldrich at his most bitter (Ulzana’s Raid). By the time he attempted to sum up his contrasting, all-consuming feelings about the form in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969), he had added a cold-eyed, ambivalent romanticism about the creation of the American West, borne of his rampant movie love, to the harsh worldview of the Dollars films, which served to enrich and expand his otherwise withering critiques of capitalist institutions of power, human nature and the bitter price of revenge.

Once Upon a Time in the West, though now considered one of the great westerns, was initially mishandled by its distributor, Paramount Pictures, and didn’t go down well with the audiences that did buy tickets. Most preferred soft and cuddly (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) or grizzled and apocalyptic (The Wild Bunch) visions of the passing of the West to Leone’s fever-dream reimagining of its genesis, or to simply precipitate the passing of the western itself by ignoring most remaining examples of them altogether. The director’s last stab at the genre (or at least the general historical period) was the raucous Duck, You Sucker (1971), starring Rod Steiger and James Coburn and set during the Mexican revolution (its original title, abandoned by Leone, was to be Once Upon a Time… The Revolution). Retitled A Fistful of Dynamite by United Artists (for plainly obvious reasons) and cut by over a half-hour, it was released into this none-too-favorable marketplace where, despite its humor and the scale of its spectacular action sequences, it made practically no impression at all.

For reasons better described in Sir Christopher Frayling’s exhaustive biography Sergio Leone: Something to Do With Death, Leone then began a long hiatus, reportedly even turning down an offer to direct The Godfather. For most of the 1970s he primarily produced and lent his name to a series of features, two of which—1973’s My Name is Nobody and 1975’s A Genius, Two Friends and an Idiot (also known in America as Trinity is Back Again, though it was not actually one of the popular Trinity comedy-westerns starring Terence Hill and Bud Spencer)-- he reportedly partially directed himself.

But in the early 1980s he reemerged with his magnificent gangster saga Once Upon a Time in America, centered upon the opium-fueled, temporally free-associative dream logic of an aging Jewish gangster contemplating the trajectory of his life and that of his childhood friends, and their place in the country in which that life of crime and betrayal once flourished and then played itself out. America was a sprawling, lyrical, lovely and brutal beast of a film, incorporating many of the stylistic tropes and thematic lines that Leone had developed over his long, and relatively unprolific, career, and it was misunderstood and butchered upon its American release—not only was the nearly four-hour film cut by nearly 90 minutes by the Ladd Company, but its radically restructured chronology was flattened out and given an ostensibly linear construct, which had the ironic effect of rendering Leone’s intricately linked story nonsensical. Pauline Kael, comparing the theatrical and restored cuts, wrote that the hacked-up version “seemed so incoherently bad that I didn’t see how the full-length film could be anything but longer,” and when she saw that full-length cut she proclaimed amazement at the difference—“I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a worse case of mutilation.”

The original cut of Once Upon a Time in America was eventually restored and shown at the New York Film Festival, and it seemed that the second act of Leone’s career as a masterful film director was about to get underway. However, in 1989, while preparing another epic, a Soviet co-production about the siege of Leningrad in World War II, Leone died unexpectedly. Largely on the strength of five major films, Leone left behind a cinematic legacy as distinctive and influential as any director in the history of cinema. And this summer the Gene Autry Museum of the American West in Griffith Park is highlighting that legacy with a film series and an exhibition entitled Once Upon a Time in Italy: The Westerns of Sergio Leone.

Cocurators Estella Chung, Autry Museum Associate Curator of Popular Culture, and Leone biographer and scholar Sir Christopher Frayling, have assembled an exhibit, which will run from July 30, 2005 to January 22, 2006, that will feature original costumes and props, set designs by production designer Carlo Simi, rare Italian and international movie posters, and original documentaries detailing Leone’s career, his passion for the Hollywood visions that informed and propelled his own imagination, and the degree to which the influence of that imagination extends throughout international cinema to this day. The exhibit promises to provide visitors with a rare and substantive collection of information and study of Sergio Leone’s life, technique and career development as a major director of cinema, as well as yet another reason for Los Angeles residents, film buffs as well as those interested in the multifaceted history of the American West, to hail and be thankful for the continued existence and prosperity of the Gene Autry Museum. For those fans of Leone’s cinema who might be reading this in other cities or countries, if you have the means (I’ve no doubt you have the desire), this might just be the ideal excuse around which to plan that vacation to Los Angeles you’ve been putting off.

Tantalizingly, the spectacular promise of the exhibit itself is just the beginning of what the Autry has in store for buffs during this Summer of Sergio. In conjunction with the Autry Museum’s presentation, the Alex Film Society will be screening the restored three-hour Italian version of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (with added scenes dubbed in English by Clint Eastwood and Eli Wallach) at the beautiful Glendale movie palace, the Alex, on July 23 at 7:00 p.m. (The Society’s Web site offers the conflicting information that the restored print being shown runs the length of the American release version— 161 minutes— but information available at the theatre itself confirms the 180-minute running time.) The screening will be preceded by a live performance from musician Alessandro Alessandroni, “the Whistler,” who recorded on Leone’s original soundtracks, as well as an introduction by Autry exhibit cocurator Sir Christopher Frayling, Rector at the Royal College of Art in London, chair of the Arts Council England, and author of Sergio Leone: Something to Do With Death, who will speak about Leone's films and his legacy. Of course, in the age of DVD and the home theater revolution, any opportunity to see The Good, the Bad and the Ugly on the big screen should be seized upon, and if you’re never seen a movie, classic or otherwise, at the Alex, I can’t imagine a better introduction to this spectacular showcase. If you are already familiar with the luxurious splendor of the Alex, no further prompting should be necessary. General admission tickets are $13.50, $9.50 for kids 12 and under, seniors 65 and older or groups of 10 or more, and $7 for Alex Film Society members, and are available daily at the Alex box office or by clicking here.

But, as they used to say on those late-night Ronco TV commercials, that’s not all. There will also be one-night only screenings of Once Upon a Time in the West (Wednesday, July 27, 8:00 pm.) and Once Upon a Time in America (Thursday, July 28, 8:00 p.m.) at the Arclight Cinemas in Hollywood. You can click here or here for further information on these screenings, though as of this writing (Sunday, June 5) none seems to have yet been posted. If you’re interested in either of these screenings (and you should be), keep checking and get your tickets as early as possible, because these special screenings at the Arclight tend to sell out fast, like hot rock concerts. And in case you missed them earlier in the week at the Alex, Mssrs. Alessandroni and Frayling will be at the Autry’s Wells Fargo Theater on Saturday, July 30 at 2:00 p.m. to introduce, in their own ways, a screening of A Fistful of Dollars. Admission is $10, $5 for Autry National Center members, and are available by clicking here.

But that’s not all! If you’re looking for entertainment under the stars, Ennio Morricone’s scores from the Leone films, plus other highlights of Italian movie music, can be heard at the Hollywood Bowl on Friday and Saturday evenings, August 26 and 27. Tickets for “La Dolce Vita: Italian Cool on a Hot Summer Night” can be purchased here or by calling 323-850-2000. And that same Saturday night, August 27, the Autry turns their south wall into an outdoor movie theater for four consecutive weeks of Leone classic westerns. You can bring blankets, chairs, food and friends, and every screening is free and open to the public. Show time is 8:00 p.m. The schedule:

Saturday, August 27: A Fistful of Dollars

Saturday, September 3: For a Few Dollars More

Saturday, September 10: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Saturday, September 17: Once Upon a Time in the West

Finally, Sir Christopher Frayling will have a new book available as an accompaniment to the exhibition, Once Upon a Time in Italy: The Westerns of Sergio Leone, that promises to be an invaluable addition to his Leone biography, Something to Do With Death and his earlier volume entitled Spaghetti Westerns. The new book is available now on a pre-order basis by clicking here .

If you’re a fan of Leone’s films, a connoisseur, devotee, appreciator, or whatever terminology you might favor, the announcement of this exhibit and screenings is true cause for celebration. The easy access to all these films on DVD is a wonderful thing in itself, but should in no way deter you from seeing them as big and wide and spectacular as they were meant to be seen (Pauline Kael once said of Leone that there wasn’t a dingy main street in any of the beat-up towns in any of his movies that didn’t seem half a mile wide from boardwalk to boardwalk). And to have available all the props, information, memorabilia and scholarship on Leone that the Autry Museum is going to be making available this summer seems to me like the best, most unexpected gift. I hope to take in as many of the screenings and as much of the museum’s other offerings as I can, and I hope you will too.

(If you're interested in more detailed biography of Leone than the one provided here, and have not yet gotten to Frayling's, there's a fine piece on the director written by Daniel Edwards that you can read here on the excellent film site Senses of Cinema.)

Another marvelous posting, and the folks at the Autry Museum ought to give you free passes for all of the good PR you have just done them. I believe I have just-- okay, I'm gonna say it-- roped my son into going to see ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST at that outdoor showing (shades of Cinema Paradiso) in September.

ReplyDeleteAs for the event at the Alex, well, I'd like to attend, but I don't think it could match the experience of watching THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY with the guys at the Nuart, highlighted by your spilling your soda all over your chair just before the lights went down for the start of the picture, leaving you to sit in the wet mess for the entire movie. I know that is one of Conboy's favorite moviegoing memories, and it ranks high on my list as well.

Thanks again for the interesting and informative piece on the great Leone. By any chance, have any of his biographers unearthed anything that might indicate whether Sergio was a baseball fan and well-versed in the intricacies of the infield fly rule?

Virgil Hilts

Virgil: I'm thinking about how I can dump another 44 oz. of soda in my lap before the show at the Alex and make it look like an accident ('cause, you know, I kinda liked it...)

ReplyDeleteLoxjet: The Dollars films are like that for me too. I grew up seeing them panned and scanned on afternoon TV, and they always seemed too big for the small screen, even though I had only a smidgen of an inkling of an idea as to why back then. When I was in college, a drive-in in Eugene actually showed, for nearly a week, as I remember, the entire Dollars trilogy PLUS Hang 'Em High-- a rare quadruple feature! But somehow my devotion to my studies prevented my attending (or maybe it was because I didn't have my car up in Eugene yet-- that's a more likely reason). I dragged Patty to a screening of A Fistful of Dollars at a theater in Santa Monica about 15 years ago, and those bastards had the audacity to show a cropped 16mm print! So the first time I ever saw anything of them projected on a big screen was when Bruce and I went to see Joe Dante give a lecture at the AMPAS Theater in Beverly Hills way back in 1987. The lecture was about horror films and their influences on his style, and the lecture was loaded with as many clips as he could fit in, all shown on the big, beautiful screen. About midway through the lecture, Dante stops and says, "And just for a break, I've got a clip here that has absolutely nothing to do with horror films, but it's from maybe my favorite movie of all time, and since I had this screen at my disposal, I just have to take the opportunity." The lights went down, and up comes the graveyard finale from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly! Spectacular! And the first time I ever saw them all the way through (projected in the proper aspect ratio..) was a double feature back in the days when the Nuart was a full-scale repertory theater. It was a double feature of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. I called in sick to work and saw nearly six hours of one of the best double features ever. I was planning to see Duck, You Sucker and Once Upon a Time in America, another six-hour double feature, the next night, but, ironically, I actually did come down with the flu and had to miss it. There's nothing like Leone on the big screen.

One of my favorites is Tuco, in the bathtub, after he's dispatched a monologuing bad guy: "If you're gonna shoot, shoot. Don't talk."

Your wonderful article got me all excited about seeing those movies, and I've never been that big a fan of them! I also want to go to this Leone event most of all(from the info on the Autry web site):

ReplyDelete"Join us for a members’ exhibition preview featuring entertainment by colossal 8-foot puppets reenacting scenes from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and demonstrations of Western-themed movie stunts."

Now exactly who came up with the idea of colossal 8-foot puppets reenacting scenes from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly?!! I like it. Really, though, any chance to see the Alex Theatre again is more than welcome, and I've always wanted to see the Autry. I'll start looking at calendars and plane fares.

they have managed to show films I don't want to see in theaters I will see them in and movies I do want to see in theaters I won't go to =) But I might try to catch some of these. My boyfriend needs more Leone education than he has....

ReplyDelete