The really good news is, according to Amazon.com, if I buy Barbara’s DVD (a production of ABC News) and the three-disc edition of The Maltese Falcon at the same time, I can save almost $10 off my total purchase!

(The following post is a belated entry in Tim Lucas's Joe Dante Blog-a-Thon, in celebration of the director's 60th birthday, which was yesterday, November 28, 2006.)

(The following post is a belated entry in Tim Lucas's Joe Dante Blog-a-Thon, in celebration of the director's 60th birthday, which was yesterday, November 28, 2006.) But I’m getting a little ahead of myself. I first became aware of Joe Dante about a week or so before I first saw The Howling, on a double feature with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that played at a now-defunct drive-in on the north end of Eugene, Oregon. The drive-in was lined all around with big pine trees, which gave the lot a distinct impression of being nestled much further away from the outskirts of town than it actually was, its secluded forestry fostering an illusion of isolation that was perfect for heightening the fear factor of both movies. Just a few days before the movie opened here, I happened to catch Dante and make-up wizard Rob Bottin on a segment of Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow program, and I was tickled by the cheek of these upstarts, who had managed to get the jump on John Landis’ more highly touted An American Werewolf in London, which would bow later that summer. They were delighting in Bottin’s revolutionary real-time werewolf transformation effects, which, for my money, far outstrip Rick Baker’s work for Landis in terms of shock and awe value, as well as in homegrown, low-budget grue-tinged surrealism. (For all its over-the-top gore, there’s nothing in American Werewolf quite as shocking as the moment when Robert Picardo picks a slug out of his skull cap just before undergoing Bottin’s presto-change-o, or the Big Bad Wolf silhouetted against those backlit blinds as he prepares to do in Dante regular Belinda Belaski.) And while they were digging getting Snyder to dig on their version of the oft-told werewolf tale, you could tell that, even though they weren’t actively putting down Landis’s film, they thought they’d done more interesting work too, and they couldn’t believe their good fortune in being able to promote it to the public ahead of time.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself. I first became aware of Joe Dante about a week or so before I first saw The Howling, on a double feature with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that played at a now-defunct drive-in on the north end of Eugene, Oregon. The drive-in was lined all around with big pine trees, which gave the lot a distinct impression of being nestled much further away from the outskirts of town than it actually was, its secluded forestry fostering an illusion of isolation that was perfect for heightening the fear factor of both movies. Just a few days before the movie opened here, I happened to catch Dante and make-up wizard Rob Bottin on a segment of Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow program, and I was tickled by the cheek of these upstarts, who had managed to get the jump on John Landis’ more highly touted An American Werewolf in London, which would bow later that summer. They were delighting in Bottin’s revolutionary real-time werewolf transformation effects, which, for my money, far outstrip Rick Baker’s work for Landis in terms of shock and awe value, as well as in homegrown, low-budget grue-tinged surrealism. (For all its over-the-top gore, there’s nothing in American Werewolf quite as shocking as the moment when Robert Picardo picks a slug out of his skull cap just before undergoing Bottin’s presto-change-o, or the Big Bad Wolf silhouetted against those backlit blinds as he prepares to do in Dante regular Belinda Belaski.) And while they were digging getting Snyder to dig on their version of the oft-told werewolf tale, you could tell that, even though they weren’t actively putting down Landis’s film, they thought they’d done more interesting work too, and they couldn’t believe their good fortune in being able to promote it to the public ahead of time. Both being graduates of the Roger Corman Film Finishing School, this was probably the first time either one had ever had such an opportunity. Hell, it was practically the first time either of them even had anything like a budget to work with. And despite Dante and actors Dee Wallace Stone and Picardo pointing out the movie’s deficiencies, budgetary or otherwise, on The Howling’s terrific DVD, it’s a movie that feels like a step away from its low-budget roots, and also a delirious reveling in them and what the director learned from his experiences. Amazingly, though he’s been involved in 12 features and many TV segments since then, this quality of youthful exuberance, as Tim Lucas rightly describes it, is a hallmark of Dante’s work. Of course, Dante also fills his frames with terrific jokes, perverse, often subversive subtexts, and off-kilter compositions-- there’s a certain Mad magazine/EC Comics influence at work here too, as well as an aesthetic allegiance to the work of the Warner Brothers cartoon stable, which juices his movies with energy and inspiration. Yet despite his being taken under the Amblin’ Entertainment umbrella, where he was ostensibly being groomed in the image of Steven Spielberg, he’s really had only one major hit in his 30-year career as a director—Amblin’s Gremlins, which many took as a none-too-subtle deconstruction of Spielberg’s Close Encounters-E.T. sensibility.

Both being graduates of the Roger Corman Film Finishing School, this was probably the first time either one had ever had such an opportunity. Hell, it was practically the first time either of them even had anything like a budget to work with. And despite Dante and actors Dee Wallace Stone and Picardo pointing out the movie’s deficiencies, budgetary or otherwise, on The Howling’s terrific DVD, it’s a movie that feels like a step away from its low-budget roots, and also a delirious reveling in them and what the director learned from his experiences. Amazingly, though he’s been involved in 12 features and many TV segments since then, this quality of youthful exuberance, as Tim Lucas rightly describes it, is a hallmark of Dante’s work. Of course, Dante also fills his frames with terrific jokes, perverse, often subversive subtexts, and off-kilter compositions-- there’s a certain Mad magazine/EC Comics influence at work here too, as well as an aesthetic allegiance to the work of the Warner Brothers cartoon stable, which juices his movies with energy and inspiration. Yet despite his being taken under the Amblin’ Entertainment umbrella, where he was ostensibly being groomed in the image of Steven Spielberg, he’s really had only one major hit in his 30-year career as a director—Amblin’s Gremlins, which many took as a none-too-subtle deconstruction of Spielberg’s Close Encounters-E.T. sensibility.

But I do have time for one pretty good Joe Dante story, one which I’ve told before (so please forgive me if one or two of the times were on this blog), one which capsulizes the outside-the-lines appeal and approach that I find so captivating and exciting about Dante’s movies. Somewhere around Halloween 1988, I talked my best friend, Bruce, into accompanying me to a lecture at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. (I didn’t really have to talk too hard.) The speaker, director Joe Dante, would be hosting an informal discussion of horror movies, fielding questions about the genre (and, presumably, his own work within it), and showing lots and lots of clips on the Academy’s spectacular big screen. I don’t really recall much of what went on that night, apart from spotting Leonard Maltin in the audience, but I certainly do recall nervously approaching the microphone to ask Dante a question about Explorers-- he confirmed my suspicions that it was a movie very close to his heart. I remember also that there were a lot of clips, some of them skirting the borders of “horror” and spilling over into suspense, science fiction and even action-adventure, and Dante’s enthusiasm for each and every one of them was palpable, contagious—we left the auditorium that night wanting to go home and rent or see everything he’d talked about, even the stuff we’d already seen a thousand times.

But I do have time for one pretty good Joe Dante story, one which I’ve told before (so please forgive me if one or two of the times were on this blog), one which capsulizes the outside-the-lines appeal and approach that I find so captivating and exciting about Dante’s movies. Somewhere around Halloween 1988, I talked my best friend, Bruce, into accompanying me to a lecture at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. (I didn’t really have to talk too hard.) The speaker, director Joe Dante, would be hosting an informal discussion of horror movies, fielding questions about the genre (and, presumably, his own work within it), and showing lots and lots of clips on the Academy’s spectacular big screen. I don’t really recall much of what went on that night, apart from spotting Leonard Maltin in the audience, but I certainly do recall nervously approaching the microphone to ask Dante a question about Explorers-- he confirmed my suspicions that it was a movie very close to his heart. I remember also that there were a lot of clips, some of them skirting the borders of “horror” and spilling over into suspense, science fiction and even action-adventure, and Dante’s enthusiasm for each and every one of them was palpable, contagious—we left the auditorium that night wanting to go home and rent or see everything he’d talked about, even the stuff we’d already seen a thousand times.  And that’s a Dante movie in a nutshell—- skewed, off-center, perverse, weirdly funny, unpredictable, deep-dish fun for fans, willing to tread just about anywhere, and close enough to a mainstream sensibility to pass (if you’re not looking too closely) as part of that mainstream. But Joe Dante at 60 is just as irreverent as he was when he took his first directing credit 30 years ago, along with Allan Arkush, on Hollywood Boulevard, and his movies have remained vital and true to his steady sense of genre intelligence and awareness of the world as well. I wish Looney Tunes would have been a success if only to have facilitated another run like he had post-Gremlins. But with the Masters of Horror series, and the unpredictable projects that will continue to pop up to delight Joe Dante fans, and Joe Dante himself, I feel confident in predicting that he’s got a long way to go. I look forward to taking that journey with him.

And that’s a Dante movie in a nutshell—- skewed, off-center, perverse, weirdly funny, unpredictable, deep-dish fun for fans, willing to tread just about anywhere, and close enough to a mainstream sensibility to pass (if you’re not looking too closely) as part of that mainstream. But Joe Dante at 60 is just as irreverent as he was when he took his first directing credit 30 years ago, along with Allan Arkush, on Hollywood Boulevard, and his movies have remained vital and true to his steady sense of genre intelligence and awareness of the world as well. I wish Looney Tunes would have been a success if only to have facilitated another run like he had post-Gremlins. But with the Masters of Horror series, and the unpredictable projects that will continue to pop up to delight Joe Dante fans, and Joe Dante himself, I feel confident in predicting that he’s got a long way to go. I look forward to taking that journey with him. 'Tis the season, as they say... for merciless stomach flu, that is. The Cozzalio household has been under siege by the meanest bug to land in these here parts in a good long while, and no one has been spared, not even the carpets (if you know what I mean). Both daughters got sick separately, on either side of Thanksgiving Day, and have been recuperating in relative silence ever since. Their mother and I were both slammed in the middle of Saturday night—the Mrs. is still reeling at home and trying to work, while I have made my way out into the brave world and am attempting to be a constructive breadwinner from the office today. (The looks from those around who don’t seem to be convinced that I’m entirely well are pretty rich, but not as rich as the ones I got in CostCo Saturday night after being vomited on while waiting in line at the register. The oh-so-accommodating and understanding dupes in Borat had nothing on these warehouse shoppers as they attempted to avert their eyes or pretend they didn’t notice as my daughter and I, covered in purplish, chunky goo, marched stiffly to the restroom.)

'Tis the season, as they say... for merciless stomach flu, that is. The Cozzalio household has been under siege by the meanest bug to land in these here parts in a good long while, and no one has been spared, not even the carpets (if you know what I mean). Both daughters got sick separately, on either side of Thanksgiving Day, and have been recuperating in relative silence ever since. Their mother and I were both slammed in the middle of Saturday night—the Mrs. is still reeling at home and trying to work, while I have made my way out into the brave world and am attempting to be a constructive breadwinner from the office today. (The looks from those around who don’t seem to be convinced that I’m entirely well are pretty rich, but not as rich as the ones I got in CostCo Saturday night after being vomited on while waiting in line at the register. The oh-so-accommodating and understanding dupes in Borat had nothing on these warehouse shoppers as they attempted to avert their eyes or pretend they didn’t notice as my daughter and I, covered in purplish, chunky goo, marched stiffly to the restroom.)  For those who don’t know the significance of Forrest J. Ackerman, I refer you to Flickhead’s excellent, very personal history of Forrest J. Ackerman’s legacy. Flickhead is busy hosting a Forrest J. Ackerman blog-a-thon in celebration of the man’s 90th birthday, which also just happens to be this very day. Lighting 90 candles is a big job, so let me offer some assistance.

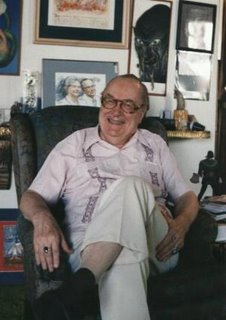

For those who don’t know the significance of Forrest J. Ackerman, I refer you to Flickhead’s excellent, very personal history of Forrest J. Ackerman’s legacy. Flickhead is busy hosting a Forrest J. Ackerman blog-a-thon in celebration of the man’s 90th birthday, which also just happens to be this very day. Lighting 90 candles is a big job, so let me offer some assistance.

About eight years later Bruce, his wife, and I were visiting the old Hollywood museum that used to be located next to the Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. The museum was packed with authentic costumes, props and other significant memorabilia from the annals of Hollywood history, and as a visitor to Los Angeles (I was still about two years away from becoming a resident) it was a fascinating place to visit. (Bruce, who had been living in Los Angeles for a couple of years by then, loved it too.) He and I got distracted by an exhibit of costumes from Gone with the Wind and were marveling over the detail on one of Scarlet’s dresses when Bruce noticed his wife over on the other side of the room talking to an older gentleman. “Look,” Bruce said, “some old guy has Pattie cornered and is telling her some story about the old days of Hollywood, and she can’t escape!” We both quietly watched and laughed for a moment or two. I don’t remember which of us noticed that the part of the room she was standing in was an exhibit of science fiction props and models and posters and such. But as soon as we did, we took a little closer look at the old guy who had Pattie’s ear. “Jesus, I think that’s Forrest J. Ackerman,” I said. Bruce quickly agreed, and we made our way across the floor, sidled up next to Pattie, introduced ourselves (I don’t remember if we told him about the phone call) and attempted to wedge ourselves into the conversation they were having. The four of us stood around, Mr. Ackerman holding court and describing several items in the display cases, which he told us were lent to the museum from his private collection. “You mean, from the Ackermansion?” Bruce asked. Forry lit up instantly and said, “Yes, indeed! You know about the Ackermansion?” We explained our lifelong connection to Famous Monsters, and he ended up extending an invitation to us to visit his famous, expansive digs in the Hollywood Hills. Why we didn’t take him up on it, I don’t remember exactly, and I’ve always regretted it. But I do remember laughing for the rest of the day at the image of Pattie stuck talking to a monster buff icon whose identify was completely unknown to her, while the big horror fans were gazing at them both from a distance, from a shrine to Tara, of all places.

About eight years later Bruce, his wife, and I were visiting the old Hollywood museum that used to be located next to the Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. The museum was packed with authentic costumes, props and other significant memorabilia from the annals of Hollywood history, and as a visitor to Los Angeles (I was still about two years away from becoming a resident) it was a fascinating place to visit. (Bruce, who had been living in Los Angeles for a couple of years by then, loved it too.) He and I got distracted by an exhibit of costumes from Gone with the Wind and were marveling over the detail on one of Scarlet’s dresses when Bruce noticed his wife over on the other side of the room talking to an older gentleman. “Look,” Bruce said, “some old guy has Pattie cornered and is telling her some story about the old days of Hollywood, and she can’t escape!” We both quietly watched and laughed for a moment or two. I don’t remember which of us noticed that the part of the room she was standing in was an exhibit of science fiction props and models and posters and such. But as soon as we did, we took a little closer look at the old guy who had Pattie’s ear. “Jesus, I think that’s Forrest J. Ackerman,” I said. Bruce quickly agreed, and we made our way across the floor, sidled up next to Pattie, introduced ourselves (I don’t remember if we told him about the phone call) and attempted to wedge ourselves into the conversation they were having. The four of us stood around, Mr. Ackerman holding court and describing several items in the display cases, which he told us were lent to the museum from his private collection. “You mean, from the Ackermansion?” Bruce asked. Forry lit up instantly and said, “Yes, indeed! You know about the Ackermansion?” We explained our lifelong connection to Famous Monsters, and he ended up extending an invitation to us to visit his famous, expansive digs in the Hollywood Hills. Why we didn’t take him up on it, I don’t remember exactly, and I’ve always regretted it. But I do remember laughing for the rest of the day at the image of Pattie stuck talking to a monster buff icon whose identify was completely unknown to her, while the big horror fans were gazing at them both from a distance, from a shrine to Tara, of all places. Thirteen years later, in 1998, I finally would take Mr. Ackerman up on his rather open-ended invitation. After having lived in Los Angeles for 11 years, I decided it was time to visit the Ackermansion before, for whatever reason, it was too late. My wife, good sport that she was (is), agreed to accompany me, and we made a pilgrimage one Saturday afternoon. Not long after our visit, he was forced to sell off his collection and vacate the house permanently, so I feel fortunate that the last time I would meet Forrest J. Ackerman in person would be when he was still surrounded by his glory, within the hallowed walls of the Ackermansion, every square inch of space taken up by the most amazing, astounding, expansive, and increasingly tattered and worn collection of horror and science fiction memorabilia ever assembled under one roof. Of course I brought my video camera and shot about 22 minutes of footage, never thinking that anyone but me, my wife, and Bruce would ever be interested in seeing it. But now, in the age of YouTube, the footage is available for anyone who cares to see the Ackermansion from the inside, in living, blood-curdling color.

Thirteen years later, in 1998, I finally would take Mr. Ackerman up on his rather open-ended invitation. After having lived in Los Angeles for 11 years, I decided it was time to visit the Ackermansion before, for whatever reason, it was too late. My wife, good sport that she was (is), agreed to accompany me, and we made a pilgrimage one Saturday afternoon. Not long after our visit, he was forced to sell off his collection and vacate the house permanently, so I feel fortunate that the last time I would meet Forrest J. Ackerman in person would be when he was still surrounded by his glory, within the hallowed walls of the Ackermansion, every square inch of space taken up by the most amazing, astounding, expansive, and increasingly tattered and worn collection of horror and science fiction memorabilia ever assembled under one roof. Of course I brought my video camera and shot about 22 minutes of footage, never thinking that anyone but me, my wife, and Bruce would ever be interested in seeing it. But now, in the age of YouTube, the footage is available for anyone who cares to see the Ackermansion from the inside, in living, blood-curdling color.

Robert Altman taught me how to see movies, and I went into his classroom kicking and screaming. As a young kid keeping up with film culture largely from the sidelines, I became obsessed, at an age far too young to actually see the movie, with Altman’s 1970 hit M*A*S*H. I read as much as I could about it— one or two reviews and the occasional newspaper article were about all I could get my hands on, but I did smuggle Richard Hooker’s novel, on which the movie was based, into my junior high locker and read it surreptitiously, voraciously. I wouldn’t see M*A*S*H in its theatrical release—I was even denied access to the slightly recut PG-rated version that bowed a few years later in re-release. The first time I actually saw M*A*S*H was when it aired on the CBS Friday Night Movie, back in the days when bowdlerized version of theatrical hits premiering on TV were mini-events of their own. It was panned-and-scanned (again, back in the days when regular citizens really had no idea what cropping movies for TV was), broken up into bits to accommodate commercials, its profanity and nudity and blood sanitized for my protection. And yet I still laughed my ass off, because I was finally getting to see some version of the film.

Robert Altman taught me how to see movies, and I went into his classroom kicking and screaming. As a young kid keeping up with film culture largely from the sidelines, I became obsessed, at an age far too young to actually see the movie, with Altman’s 1970 hit M*A*S*H. I read as much as I could about it— one or two reviews and the occasional newspaper article were about all I could get my hands on, but I did smuggle Richard Hooker’s novel, on which the movie was based, into my junior high locker and read it surreptitiously, voraciously. I wouldn’t see M*A*S*H in its theatrical release—I was even denied access to the slightly recut PG-rated version that bowed a few years later in re-release. The first time I actually saw M*A*S*H was when it aired on the CBS Friday Night Movie, back in the days when bowdlerized version of theatrical hits premiering on TV were mini-events of their own. It was panned-and-scanned (again, back in the days when regular citizens really had no idea what cropping movies for TV was), broken up into bits to accommodate commercials, its profanity and nudity and blood sanitized for my protection. And yet I still laughed my ass off, because I was finally getting to see some version of the film. Then came the summer of 1975. Kael’s famous (in some circles, infamous) rave for Nashville paved the way for its studio, Paramount, to expect a big hit. And although the movie was a high-profile release that garnered similarly moonstruck reviews from almost every critic, in box-office terms the movie did not, as Kael put it, zoom off into the stratosphere. Another picture, released a week later, did instead—it was called Jaws. I was 15 years old, and that was the movie I wanted to see. Nashville, a movie about which I barely had an understanding, in terms of “plot” or anything else that might conceivably hook me into it, could wait.

Then came the summer of 1975. Kael’s famous (in some circles, infamous) rave for Nashville paved the way for its studio, Paramount, to expect a big hit. And although the movie was a high-profile release that garnered similarly moonstruck reviews from almost every critic, in box-office terms the movie did not, as Kael put it, zoom off into the stratosphere. Another picture, released a week later, did instead—it was called Jaws. I was 15 years old, and that was the movie I wanted to see. Nashville, a movie about which I barely had an understanding, in terms of “plot” or anything else that might conceivably hook me into it, could wait. Two more years would pass, years during which I began to stretch a little bit of the hometown cocoon out of my hair and off my back and learn a little bit about life’s demands and disappointments (all in the context of the relatively protected university setting, of course). I had finally seen a few things and been through a few things and learned about a lot of things that were uncomfortable, disturbing, challenging to my smug assurance that I knew so very much about films and music and the way people interacted with each other, the way the world turned. Then one night my best friend announced that he had been reading about Nashville and wanted to see it again, this time on the big screen. (His first encounter had been that muddied-up ABC version.) So off to the cinema we went.

Two more years would pass, years during which I began to stretch a little bit of the hometown cocoon out of my hair and off my back and learn a little bit about life’s demands and disappointments (all in the context of the relatively protected university setting, of course). I had finally seen a few things and been through a few things and learned about a lot of things that were uncomfortable, disturbing, challenging to my smug assurance that I knew so very much about films and music and the way people interacted with each other, the way the world turned. Then one night my best friend announced that he had been reading about Nashville and wanted to see it again, this time on the big screen. (His first encounter had been that muddied-up ABC version.) So off to the cinema we went. I’d seen Three Women and A Wedding and Quintet in theatrical release, and in the fall of 1980, my senior year at the University of Oregon, as if by providence, my film professor ran an entire term of Altman films, starting with M*A*S*H and going all the way up through Three Women, to be capped by that year’s Christmas release of Popeye. It was, needless to say, a revelatory experience, and I’ve seen most of those films three, four, five, ten times again since then. And the day that the professor screened Nashville, I was there for the 7:00 a.m. preview screening and the midday preview screening, both held for students who could not make the regularly scheduled 7:00 p.m. evening screening. And I was there at 7:00 p.m. too. No movie I’d already seen ever looked the same to me again after seeing Nashville, and every movie I saw after these screenings, and I mean every movie, I would see through the prism of Altman’s great, pulsating, vibrating, living and breathing vision of this country.

I’d seen Three Women and A Wedding and Quintet in theatrical release, and in the fall of 1980, my senior year at the University of Oregon, as if by providence, my film professor ran an entire term of Altman films, starting with M*A*S*H and going all the way up through Three Women, to be capped by that year’s Christmas release of Popeye. It was, needless to say, a revelatory experience, and I’ve seen most of those films three, four, five, ten times again since then. And the day that the professor screened Nashville, I was there for the 7:00 a.m. preview screening and the midday preview screening, both held for students who could not make the regularly scheduled 7:00 p.m. evening screening. And I was there at 7:00 p.m. too. No movie I’d already seen ever looked the same to me again after seeing Nashville, and every movie I saw after these screenings, and I mean every movie, I would see through the prism of Altman’s great, pulsating, vibrating, living and breathing vision of this country. I feel, in a very real, substantial way, the way I always have when I’ve heard of a favorite teacher’s passing. And that’s how I’ve come to see Robert Altman, as perhaps the best teacher of film it’s ever been my privilege, through his films, of knowing. Thank you, sir, and God bless.

I feel, in a very real, substantial way, the way I always have when I’ve heard of a favorite teacher’s passing. And that’s how I’ve come to see Robert Altman, as perhaps the best teacher of film it’s ever been my privilege, through his films, of knowing. Thank you, sir, and God bless. This week at the Drive-in Trailer Park it’s James Bond week. To commemorate the release of the 21st official 007 movie, Casino Royale, I’m reaching back to about 1973 for a drive-in ad culled from the early ‘70s re-release of a Connery Bond triple feature, most likely intended to make the transition to the Roger Moore era a smoother one. The ozoner was getting rid for a double feature comprised of faux porn and a barely raunchy sex comedy starring Larry Hagman and Joan Collins, so it’s unlikley anyone mourned this partciular eviction for too long, even if the new tenants were anywhere from eight to 12 years old. Seems that the ad copy guy at the newspaper was having a bit of fun at Her Majesty’s operative’s expense, however—“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to have thighs!”

This week at the Drive-in Trailer Park it’s James Bond week. To commemorate the release of the 21st official 007 movie, Casino Royale, I’m reaching back to about 1973 for a drive-in ad culled from the early ‘70s re-release of a Connery Bond triple feature, most likely intended to make the transition to the Roger Moore era a smoother one. The ozoner was getting rid for a double feature comprised of faux porn and a barely raunchy sex comedy starring Larry Hagman and Joan Collins, so it’s unlikley anyone mourned this partciular eviction for too long, even if the new tenants were anywhere from eight to 12 years old. Seems that the ad copy guy at the newspaper was having a bit of fun at Her Majesty’s operative’s expense, however—“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to have thighs!” I could not find a trailer for the 1950 film version of Cheaper by the Dozen (although trailers for the crass Steve Martin remake and its sequel are all over the Internet), so I’ve settled for the Clifton Webb connection— here then is Webb, Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Wagner and a host of others starring in Jean Negulesco’s 1953 Titanic.

I could not find a trailer for the 1950 film version of Cheaper by the Dozen (although trailers for the crass Steve Martin remake and its sequel are all over the Internet), so I’ve settled for the Clifton Webb connection— here then is Webb, Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Wagner and a host of others starring in Jean Negulesco’s 1953 Titanic.

Jim Emerson has had a virtual comedy symposium going on over at Scanners for a couple of weeks, sparked perhaps by Borat, but also by some general musings about why some movies or comedy bits or actors make us laugh and some don’t make us laugh, perhaps as mysterious a subject as there is in a consideration of the movies. Sometimes laughter seems inexplicable; something will strike you funny, and perhaps your reaction to it might seem oversized, given the amount of energy to get the laugh in the first place—I think of just about any expression that comes across the face of bulldog character actor Eugene Pallette and am likely to split a seam laughing, though you’ll never catch Pallette working too hard for that result. But even when you think you don’t really “know” why some bit or a line hits you just right, if you think about it (and it doesn’t diminish the comedy if you do), you could probably figure it out.

Jim Emerson has had a virtual comedy symposium going on over at Scanners for a couple of weeks, sparked perhaps by Borat, but also by some general musings about why some movies or comedy bits or actors make us laugh and some don’t make us laugh, perhaps as mysterious a subject as there is in a consideration of the movies. Sometimes laughter seems inexplicable; something will strike you funny, and perhaps your reaction to it might seem oversized, given the amount of energy to get the laugh in the first place—I think of just about any expression that comes across the face of bulldog character actor Eugene Pallette and am likely to split a seam laughing, though you’ll never catch Pallette working too hard for that result. But even when you think you don’t really “know” why some bit or a line hits you just right, if you think about it (and it doesn’t diminish the comedy if you do), you could probably figure it out. But I also think that when you’re in the presence of greatness, as you usually are when you’re watching Catherine O’Hara do just about anything, but particularly when she inhabits her wobbly chanteuse Lola Heatherton on the old SCTV series, sometimes it is enough to just be in the presence and let the laughs wash over you like a wave, or prick you like a flowery cactus. Really great character comedy of the caliber that O’Hara achieved with this particular creation isn’t comprised of jokes, it’s comprised of observation, of slightly exaggerated reality, of recognizable human foibles—vanity, overreaching ambition, foolishness—woven into a fabric that only has to be touched to give up some of the treasures it has to offer.

But I also think that when you’re in the presence of greatness, as you usually are when you’re watching Catherine O’Hara do just about anything, but particularly when she inhabits her wobbly chanteuse Lola Heatherton on the old SCTV series, sometimes it is enough to just be in the presence and let the laughs wash over you like a wave, or prick you like a flowery cactus. Really great character comedy of the caliber that O’Hara achieved with this particular creation isn’t comprised of jokes, it’s comprised of observation, of slightly exaggerated reality, of recognizable human foibles—vanity, overreaching ambition, foolishness—woven into a fabric that only has to be touched to give up some of the treasures it has to offer.  The Big Lebowski (1998; Joel and Ethan Coen) It got some of the most indifferent reviews of the Coen Brothers’ career, coming directly after Fargo, but this is actually one of their most intricately written, robustly performed movies and certainly their funniest. One gasping-for-breath highlight is Walter’s observation regarding one of his cultural heroes—

The Big Lebowski (1998; Joel and Ethan Coen) It got some of the most indifferent reviews of the Coen Brothers’ career, coming directly after Fargo, but this is actually one of their most intricately written, robustly performed movies and certainly their funniest. One gasping-for-breath highlight is Walter’s observation regarding one of his cultural heroes— Blazing Saddles (1974; Mel Brooks) There were a couple of Woody Allen comedies I saw (Bananas, Sleeper) before I was exposed to Blazing Saddles, but Brooks’ western send-up was the first movie that made me howl and gasp and clutch my sides for almost a full 90 minutes. Several people in my high school approached me the day after I saw it at the hometown movie house and said, “Hey, I heard you at the movies last night!” So of course I had to see it again that very evening. I’d did it for Randolph Scott, but most of all I did it because it felt so good. Mongo punching the horse, the “Rock Ridge” musical montage that introduces us to the town, and, of course, the campfire scene are all classics, but the line that made me laugh the hardest when I saw it last year was Sheriff Bart’s plea to the townspeople to stick by him and recognize that evil Hedley Lamarr’s imminent assault on their town might just be a signal that the villain is at the end of his rope:

Blazing Saddles (1974; Mel Brooks) There were a couple of Woody Allen comedies I saw (Bananas, Sleeper) before I was exposed to Blazing Saddles, but Brooks’ western send-up was the first movie that made me howl and gasp and clutch my sides for almost a full 90 minutes. Several people in my high school approached me the day after I saw it at the hometown movie house and said, “Hey, I heard you at the movies last night!” So of course I had to see it again that very evening. I’d did it for Randolph Scott, but most of all I did it because it felt so good. Mongo punching the horse, the “Rock Ridge” musical montage that introduces us to the town, and, of course, the campfire scene are all classics, but the line that made me laugh the hardest when I saw it last year was Sheriff Bart’s plea to the townspeople to stick by him and recognize that evil Hedley Lamarr’s imminent assault on their town might just be a signal that the villain is at the end of his rope:  Buffet Froid (1979; Bertrand Blier) Blier’s surreal urban landscape of alienation, in which Gerard Depardieu finds himself involved in an escalating series of senseless murders, just gets odder and odder as it goes along. But each gasp of horror expelled by Depardieu’s Alphonse Tram finds its opposite in my equally perplexed fits of giggles, until the film finally sucks both Tram and the audience down the rabbit hole altogether.

Buffet Froid (1979; Bertrand Blier) Blier’s surreal urban landscape of alienation, in which Gerard Depardieu finds himself involved in an escalating series of senseless murders, just gets odder and odder as it goes along. But each gasp of horror expelled by Depardieu’s Alphonse Tram finds its opposite in my equally perplexed fits of giggles, until the film finally sucks both Tram and the audience down the rabbit hole altogether. Cold Turkey (1970; Bud Yorkin) Speaking of escalating madness, how about the poor, nicotine-addicted citizens of Eagle Rock, Iowa, who become the focus of a Big Tobacco publicity stunt—if they can quit smoking for one month, they’ll win $25 million. The comedy is rooted in sharp, mean character observation and packed with hilarious moments courtesy of a who’s-who comedy cast that includes Dick Van Dyke, Bob Newhart, Bob and Ray, Jean Stapleton, Graham Jarvis and a host of others.

Cold Turkey (1970; Bud Yorkin) Speaking of escalating madness, how about the poor, nicotine-addicted citizens of Eagle Rock, Iowa, who become the focus of a Big Tobacco publicity stunt—if they can quit smoking for one month, they’ll win $25 million. The comedy is rooted in sharp, mean character observation and packed with hilarious moments courtesy of a who’s-who comedy cast that includes Dick Van Dyke, Bob Newhart, Bob and Ray, Jean Stapleton, Graham Jarvis and a host of others. Dumb and Dumber (1994; Peter and Bobby Farrelly) “That John Denver was full of shit!”

Dumb and Dumber (1994; Peter and Bobby Farrelly) “That John Denver was full of shit!” Horsefeathers (1933; Norman Z. Macleod) My introduction to Groucho, Chico, Harpo and, yes, Zeppo, came on a rainy Saturday afternoon airing of this classic on TV. For some reason I decided to tape the audio on my cassette recorder, so to this day there is somewhere in a box in my closet a recording of me howling like a maniac when Harpo, driving Professor Wagstaff around the first of many bends, proves he can burn the candle at both ends...

Horsefeathers (1933; Norman Z. Macleod) My introduction to Groucho, Chico, Harpo and, yes, Zeppo, came on a rainy Saturday afternoon airing of this classic on TV. For some reason I decided to tape the audio on my cassette recorder, so to this day there is somewhere in a box in my closet a recording of me howling like a maniac when Harpo, driving Professor Wagstaff around the first of many bends, proves he can burn the candle at both ends... Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949; Robert Hamer) The term “black comedy” gets tossed around a lot to describe various gross-outs and over-the-top assault exercises these days. But this Ealing Studios effort, as purposefully genteel in appearance as the smooth surfaces of British codes of behavior that often serve to hide the most ghastly attitudes, is as pitch-black as any ever made. We’re seduced into sympathizing with the film’s narrator (Dennis Price), a murderer who commits his crimes out of a sense of thwarted entitlement, and when the movie delivers its final twist, it’s bone-chilling and hilarious.

Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949; Robert Hamer) The term “black comedy” gets tossed around a lot to describe various gross-outs and over-the-top assault exercises these days. But this Ealing Studios effort, as purposefully genteel in appearance as the smooth surfaces of British codes of behavior that often serve to hide the most ghastly attitudes, is as pitch-black as any ever made. We’re seduced into sympathizing with the film’s narrator (Dennis Price), a murderer who commits his crimes out of a sense of thwarted entitlement, and when the movie delivers its final twist, it’s bone-chilling and hilarious. The Lady Eve (1941; Preston Sturges) There aren’t many movies, comedies or otherwise, I might be tempted to describe as perfect, but this would be one of them. Perhaps Preston Sturges’ finest hour, this is an essential example of the screwball comedy. Barbara Stanwyck would never be sexier, and who knew Henry Fonda could take a fall like that?

The Lady Eve (1941; Preston Sturges) There aren’t many movies, comedies or otherwise, I might be tempted to describe as perfect, but this would be one of them. Perhaps Preston Sturges’ finest hour, this is an essential example of the screwball comedy. Barbara Stanwyck would never be sexier, and who knew Henry Fonda could take a fall like that?  Local Hero (1983; Bill Forsyth) As has been asked more than once on this blog, what ever happened to Bill Forsyth? The man has virtually dropped off the map, and yet he practically redefined “whimsical” and made the whole idea of whimsy palatable again in a very non-whimsical time (the ‘80s) through a series of delightful, off-kilter, minor-key comedies. And Local Hero is the best of them. No other movie I can think of has made me laugh so hard, made a remote place on Earth (the Scottish coast) seem more beautiful than is possible, and then broken my heart with wistful longing so thoroughly. (See also Comfort and Joy.)

Local Hero (1983; Bill Forsyth) As has been asked more than once on this blog, what ever happened to Bill Forsyth? The man has virtually dropped off the map, and yet he practically redefined “whimsical” and made the whole idea of whimsy palatable again in a very non-whimsical time (the ‘80s) through a series of delightful, off-kilter, minor-key comedies. And Local Hero is the best of them. No other movie I can think of has made me laugh so hard, made a remote place on Earth (the Scottish coast) seem more beautiful than is possible, and then broken my heart with wistful longing so thoroughly. (See also Comfort and Joy.) The Man With Two Brains (1983; Carl Reiner) For some, it's The Jerk ("It's him! It's him! What's him doing here?!"). But for me the apex of Steve Martin's career in comedy cinema came with this giddy marvel ("Clamp... Metzenbaum scissors... Somebody get that cat outta here...") in which, among other things, the eternal mystery of Merv Griffin is finally solved.

The Man With Two Brains (1983; Carl Reiner) For some, it's The Jerk ("It's him! It's him! What's him doing here?!"). But for me the apex of Steve Martin's career in comedy cinema came with this giddy marvel ("Clamp... Metzenbaum scissors... Somebody get that cat outta here...") in which, among other things, the eternal mystery of Merv Griffin is finally solved.  Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983; Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam) The Circus's most caustic movie. More laughs per minute in this one than any of their other comedies, by my jolly estimation, and worth mentioning if only for the cut to Terry Jones (in drag) washing dishes in a dreary Yorkshire kitchen as another in a seemingly endless series of newborn babies drops unceremoniously, and barely acknowledged, from under her dress and onto the floor… leading, of course, into “Every Sperm Is Sacred.”

Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983; Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam) The Circus's most caustic movie. More laughs per minute in this one than any of their other comedies, by my jolly estimation, and worth mentioning if only for the cut to Terry Jones (in drag) washing dishes in a dreary Yorkshire kitchen as another in a seemingly endless series of newborn babies drops unceremoniously, and barely acknowledged, from under her dress and onto the floor… leading, of course, into “Every Sperm Is Sacred.” National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978; John Landis) Aside from its uncanny ability to populate its well-observed locations with unusually authentic and riotously funny “atmospheric background casting,” this movie is the rare beast that actually seems to get funnier with each passing year. Personal highlights: Dean Wormer trying to unravel a phone cord from his deliriously drunken wife’s thigh; and the title card “Greg Marmalard ‘63, Nixon White House Aide, Raped in Prison ‘74." The last true blooming of the uncut Lampoon spirit before it gave way to the Griswold family, grisly sentimentality, and an unfortunately resilient reputation for bad movie comedy.

National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978; John Landis) Aside from its uncanny ability to populate its well-observed locations with unusually authentic and riotously funny “atmospheric background casting,” this movie is the rare beast that actually seems to get funnier with each passing year. Personal highlights: Dean Wormer trying to unravel a phone cord from his deliriously drunken wife’s thigh; and the title card “Greg Marmalard ‘63, Nixon White House Aide, Raped in Prison ‘74." The last true blooming of the uncut Lampoon spirit before it gave way to the Griswold family, grisly sentimentality, and an unfortunately resilient reputation for bad movie comedy. A New Leaf (1971; Elaine May) Cut from the same cloth as Kind Hearts and Coronets (but, unlike that film, not quite able to see the grimmest strand of its storyline through to the bitter end, courtesy of studio interference), this nearly forgotten comedy is an oddball treasure. A spoiled trust-fund ne’er-do-well (Walter Matthau) is staring down the possibility of his money teat drying up, so he convinces a clumsy, ugly-duckling botanist (May), who happens to be super-wealthy, that he loves her, all the while planning to kill her and steal her fortune. The movie is anything but smooth sailing, narratively speaking (It was taken away from May and recut before release), but it’s still a marvel to behold these two great comedic performances wringing laughs out of humiliation, horror and maybe even true love. (I doubt we’ll ever see the movie May wanted to show us, but I still hope there’s a future on DVD for this one, even just the theatrical version.)

A New Leaf (1971; Elaine May) Cut from the same cloth as Kind Hearts and Coronets (but, unlike that film, not quite able to see the grimmest strand of its storyline through to the bitter end, courtesy of studio interference), this nearly forgotten comedy is an oddball treasure. A spoiled trust-fund ne’er-do-well (Walter Matthau) is staring down the possibility of his money teat drying up, so he convinces a clumsy, ugly-duckling botanist (May), who happens to be super-wealthy, that he loves her, all the while planning to kill her and steal her fortune. The movie is anything but smooth sailing, narratively speaking (It was taken away from May and recut before release), but it’s still a marvel to behold these two great comedic performances wringing laughs out of humiliation, horror and maybe even true love. (I doubt we’ll ever see the movie May wanted to show us, but I still hope there’s a future on DVD for this one, even just the theatrical version.) 1941 (1979; Steven Spielberg) One of the great symbols of wretched excess in film history is actually a gargantuan comedy that still has room for the occasional light touch-- John Williams’ orchestral pixie dust that accompanies the puffs of smoke emanating from John Belushi’s stogie, for example. 1941 is the most unruly movie Spielberg, who directed from a script by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, has ever made, and given that unruliness, it has some of the most amazing comic set pieces ever staged—the U.S.O. dance, the attack on Hollywood Boulevard, the systematic destruction of Ned Beatty’s impossibly located seaside home. And it’s so crammed with terrific actors doing hilarious things—Belushi, Slim Pickens, Warren Oates, Robert Stack, John Candy, et al, that I can barely think of it without at least smiling. The big laughs come when I watch it, as I anticipate doing again and again. (For another great Zemeckis/Gale contribution to pitch-black comedy, see Used Cars.)

1941 (1979; Steven Spielberg) One of the great symbols of wretched excess in film history is actually a gargantuan comedy that still has room for the occasional light touch-- John Williams’ orchestral pixie dust that accompanies the puffs of smoke emanating from John Belushi’s stogie, for example. 1941 is the most unruly movie Spielberg, who directed from a script by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, has ever made, and given that unruliness, it has some of the most amazing comic set pieces ever staged—the U.S.O. dance, the attack on Hollywood Boulevard, the systematic destruction of Ned Beatty’s impossibly located seaside home. And it’s so crammed with terrific actors doing hilarious things—Belushi, Slim Pickens, Warren Oates, Robert Stack, John Candy, et al, that I can barely think of it without at least smiling. The big laughs come when I watch it, as I anticipate doing again and again. (For another great Zemeckis/Gale contribution to pitch-black comedy, see Used Cars.) One Two Three (1961; Billy Wilder) "Those East Germans’ll be on you like the hot breath of the Cossacks!" So will this movie. Cagney’s breathless blowhard, a Coca-Cola magnate who straddles the Berlin Wall in an attempt to keep his boss's daughter from dallying on the Communist side with a handsome Bolshevik, sets the pace for what may be the most ruthlessly rapid-fire comedy ever made.

One Two Three (1961; Billy Wilder) "Those East Germans’ll be on you like the hot breath of the Cossacks!" So will this movie. Cagney’s breathless blowhard, a Coca-Cola magnate who straddles the Berlin Wall in an attempt to keep his boss's daughter from dallying on the Communist side with a handsome Bolshevik, sets the pace for what may be the most ruthlessly rapid-fire comedy ever made. Richard Pryor Live In Concert (1979; Jeff Margolis) I’m not sure what I was expecting when I wandered into this movie during my sophomore year in college, but what I nearly got was cardiac arrest from laughing, the real fear of which was intensified by Pryor’s agonizingly funny re-creation of his own heart attack (His pained whimpering gets this response from his angry organ as it applies yet another horrendous squeeze: “Shoulda thought about that when you was eatin’ all that pork!”) A brilliant performance. I honestly fear for my own life whenever I watch this movie.

Richard Pryor Live In Concert (1979; Jeff Margolis) I’m not sure what I was expecting when I wandered into this movie during my sophomore year in college, but what I nearly got was cardiac arrest from laughing, the real fear of which was intensified by Pryor’s agonizingly funny re-creation of his own heart attack (His pained whimpering gets this response from his angry organ as it applies yet another horrendous squeeze: “Shoulda thought about that when you was eatin’ all that pork!”) A brilliant performance. I honestly fear for my own life whenever I watch this movie. Rock-A-Bye Bear (1952; Tex Avery) More laughs per square inch and second of running time (seven minutes) than any movie I’ve ever seen. This Tex Avery MGM cartoon features Spike the bulldog getting a job guarding the winter home of the world’s most noise-sensitive hibernating bear. Heart-stopping, liver-collapsing, lung-shattering, eyeball-exploding laughter ensues. You may not make it out the other end alive. I didn’t.

Rock-A-Bye Bear (1952; Tex Avery) More laughs per square inch and second of running time (seven minutes) than any movie I’ve ever seen. This Tex Avery MGM cartoon features Spike the bulldog getting a job guarding the winter home of the world’s most noise-sensitive hibernating bear. Heart-stopping, liver-collapsing, lung-shattering, eyeball-exploding laughter ensues. You may not make it out the other end alive. I didn’t. South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut (1999; Trey Parker) The movie that’s bold enough to ask: “What the fuck is wrong with German people?” Screamingly hilarious satire that leaves no sacred cow unbutchered. Leatherface had nothing on the slash-and-burn tactics of this movie. David Edelstein accurately described it as this generation’s Duck Soup.

South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut (1999; Trey Parker) The movie that’s bold enough to ask: “What the fuck is wrong with German people?” Screamingly hilarious satire that leaves no sacred cow unbutchered. Leatherface had nothing on the slash-and-burn tactics of this movie. David Edelstein accurately described it as this generation’s Duck Soup. Tanner ‘88 (1988; Robert Altman) Altman fans and political junkies know how hilarious this movie is, and there’s hardly a “joke” in it. But this is a hilarious movie. What seemed daring and mind-boggling in 1988 still seems daring and mind-boggling, but looking at the movie from the perspective of six years of the Bush administration, and a through-the-wrong-end-of-the looking-glass view of America before 9/11, the laughs tend to stick in the throat a little more than they did before. Even so, this is perhaps the greatest instance of Altman’s wizardly ability (helped along considerably by Garry Trudeau’s writing) to tease consistent laughter not out of situations, but out of the simple (and incredibly complex) way humans—politicos or no—communicate and interact and bludgeon each other with propaganda and disinformation. And have Pamela Reed or Michael Murphy ever been this good?

Tanner ‘88 (1988; Robert Altman) Altman fans and political junkies know how hilarious this movie is, and there’s hardly a “joke” in it. But this is a hilarious movie. What seemed daring and mind-boggling in 1988 still seems daring and mind-boggling, but looking at the movie from the perspective of six years of the Bush administration, and a through-the-wrong-end-of-the looking-glass view of America before 9/11, the laughs tend to stick in the throat a little more than they did before. Even so, this is perhaps the greatest instance of Altman’s wizardly ability (helped along considerably by Garry Trudeau’s writing) to tease consistent laughter not out of situations, but out of the simple (and incredibly complex) way humans—politicos or no—communicate and interact and bludgeon each other with propaganda and disinformation. And have Pamela Reed or Michael Murphy ever been this good? Boys and ghouls, Forrest J. Ackerman, founder and publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland and hero to a generation of monster movie geeks, the ranks of which include Steven Spielberg, Stephen King, Joe Dante, John Landis and many others, turns 90 years old next Friday, November 24. As a way of saying happy birthday to Forry, number-one resident of Horrorwood, Karloffornia, Flickhead will be hosting a blog-a-thon that day from his eponymous blog to celebrate this milestone.

Boys and ghouls, Forrest J. Ackerman, founder and publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland and hero to a generation of monster movie geeks, the ranks of which include Steven Spielberg, Stephen King, Joe Dante, John Landis and many others, turns 90 years old next Friday, November 24. As a way of saying happy birthday to Forry, number-one resident of Horrorwood, Karloffornia, Flickhead will be hosting a blog-a-thon that day from his eponymous blog to celebrate this milestone. I know Flickhead would love to see testimony and tribute from everybody for whom Forry was a major childhood influence, in the hope that we can help make it a special birthday indeed and somehow get word of our endeavor to Mr. Ackerman himself. (Speaking of hopes, maybe Tim Lucas can get word to some of those notables that he knows and give them a chance to chime in too!) And as always, if you are blogless but would still like to write something in tribute to the curator of the Ackermuseum, please feel free to contact me by e-mail and I will be glad to post your contribution alongside my own next Friday. Flickhead will undoubtedly be posting links to all the contributors on his Forrest J. Ackerman Blog-a-Thon home page on Friday as well..

I know Flickhead would love to see testimony and tribute from everybody for whom Forry was a major childhood influence, in the hope that we can help make it a special birthday indeed and somehow get word of our endeavor to Mr. Ackerman himself. (Speaking of hopes, maybe Tim Lucas can get word to some of those notables that he knows and give them a chance to chime in too!) And as always, if you are blogless but would still like to write something in tribute to the curator of the Ackermuseum, please feel free to contact me by e-mail and I will be glad to post your contribution alongside my own next Friday. Flickhead will undoubtedly be posting links to all the contributors on his Forrest J. Ackerman Blog-a-Thon home page on Friday as well.. Whatever side of the fence you end up on with Martin Scorsese films like Gangs of New York, The Aviator and The Departed, one thing seems inarguable—the man is an invaluable force in the field of film preservation. His latest announced endeavor, a three-year initiative launched by the director and organizers behind the fledging Rome Film Festival, aims to preserve a slate of Italian films heretofore fallen under the evil influence of scratches, fading, discoloration and other abuses. The titles of the films under consideration have yet to be decided upon, save for one: Sergio Leone’s masterpiece Once Upon a Time in the West will get the full restoration wash-and-wax in time to be unveiled next fall at the second Rome Film Festival.

Whatever side of the fence you end up on with Martin Scorsese films like Gangs of New York, The Aviator and The Departed, one thing seems inarguable—the man is an invaluable force in the field of film preservation. His latest announced endeavor, a three-year initiative launched by the director and organizers behind the fledging Rome Film Festival, aims to preserve a slate of Italian films heretofore fallen under the evil influence of scratches, fading, discoloration and other abuses. The titles of the films under consideration have yet to be decided upon, save for one: Sergio Leone’s masterpiece Once Upon a Time in the West will get the full restoration wash-and-wax in time to be unveiled next fall at the second Rome Film Festival. When I saw it the summer before last on the big screen at the Arclight Cinemas in Hollywood, I thought it already looked pretty damn good—the symptoms described in the Los Angeles Times Calendar section yesterday didn’t seem to be afflicting the print I saw. But any effort to preserve and spruce up a great movie like this one is, I think, to be applauded, especially since there don’t seem to be any plans to piece together a different, “expanded” version. Perhaps the Rome Film Festival appearance will be the forerunner to a modest big-screen re-release in the States as well. I’ll keep you posted. Cue Harmonica.

When I saw it the summer before last on the big screen at the Arclight Cinemas in Hollywood, I thought it already looked pretty damn good—the symptoms described in the Los Angeles Times Calendar section yesterday didn’t seem to be afflicting the print I saw. But any effort to preserve and spruce up a great movie like this one is, I think, to be applauded, especially since there don’t seem to be any plans to piece together a different, “expanded” version. Perhaps the Rome Film Festival appearance will be the forerunner to a modest big-screen re-release in the States as well. I’ll keep you posted. Cue Harmonica.