Ladies and gentlemen, faithful readers of

SLIFR, the impossible has happened-- a day late for the party, perhaps, but it has happened nonetheless. After missing out entirely on the past three quizzes, I’ve managed to muster the energy and resources to take on

Dr. Anton Phibes’ Abominably Erudite, Musically Malignant, Cursedly Clever Halloween Movie Quiz! Even though this is a Halloween-oriented quiz, I feel justified in my tardiness because I don’t believe anyone stops watching horror movies simply because Halloween is over. They may want to take a break, sure, but the subject remains of interest into November. This is my arrogant assumption, however, and while I beg the good doctor’s forgiveness that I couldn’t get my paper turned in before the commencement of trick-or-treating, I hope he and you will accept it in the evil and nasty spirit with which it was intended and conceived. After all, I

am Satan! Here, then, are the things this quiz, and some of your answers to it, made me think about. Hope your Halloween was a

gore-ious one!

*********************************************

1) Favorite Vincent Price/American International Pictures release.

Well, if the wording were “best” I might well have to choose

The Masque of the Red Death, which has spectacularly doom-laden atmosphere and the best use of color of all of Price’s Corman/Poe pictures (courtesy of cinematographer Nicolas Roeg), or maybe even

The Conqueror Worm, though it’s a severely unpleasant, almost suffocating movie to sit through. But no, the word is “favorite,” and since this is the case there can be only one choice for me. I hope everyone will understand that I am not sucking up to the host of this here quiz by choosing

The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971).

Phibes may not even be Price’s best performance, AIP or not, but it’s got gore, humor, music (that organ theme played over the opening credits has been permanently, pleasurably burned into my brain), a wonderful supporting cast and visual panache to burn. But most of all, it was the gateway movie for me to all the other Vincent Price/AIP pictures—it was only after

Phibes that I really started seeking out all those other movies I saw stills from so often in

Famous Monsters of Filmland. My mom drove me and a friend to a neighboring town to see

Phibes the weekend it opened during the summer of 1971 as a birthday present when I was 11 years old, and it made an impression on me that surpassed any horror movie I’d yet seen in a theater. (I was already a veteran of several Hammer films and

The Fearless Vampire Killers… courtesy of my local movie house.) My own daughter, currently also age 11, watched a DVD of it yesterday as a preamble to an evening of trick-or-treating, and when I told her I was terrified when I saw it at her age for the first time she looked at me like I was a demented old man. She liked the movie but could not understand how anyone could find it terrifying. And I thought to myself again how glad I was that I’d grown up during a time in movie history when a picture like

The Abominable Dr. Phibes could still be scary and fun for a mass audience, and that I got to see it when I did.

2) What horror classic (or non-classic) that has not yet been remade would you like to see upgraded for modern audiences?

First of all, I don’t have a philosophical objection to remakes. The fact that 9 out of 10 remakes bring nothing new (or, worse, the same old “new” thing) to the table doesn’t change the fact that every once in a while a movie like

Let the Right One In will inspire a

Let Me In, and now all of the sudden we have two great movies to enjoy. The problem that I have with this question is that I can imagine even the duller candidates for refashioning that I might think of would probably be preferable to what they might be turned into by some young filmmaker trying to make a splash and a career by revamping a well-known title. What are the odds that if someone tried redoing, say,

The Green Slime it would retain any of the kind of cheesy energy that makes the original fun to watch to this day? The remake would have to be all post-

Alien serious and grim and excessively gooey in order to past muster in the age of Marcus Nispel and Alexandre Aja. That said, as much as I think the originals are better than fine as is, I probably would line up to see what CGI miracles could be conjured for

Tarantula and/or

The Incredible Shrinking Man, but only with the caveat that they be approached straight, without gimmicks or wink-wink-nudge-nudgery. But I think the best answer for me here, since we’re already in the neighborhood of creatures made giant, and men made small, would be to see a movie made of H.G. Wells’

The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth that stayed true to Wells’ vision and didn’t just use it as an excuse to see Ida Lupino and Marjoe Gortner being chased by giant chickens.

3) Jonathan Frid or Thayer David?

David had an amazing, imposing presence and an unforgettable, drawn-out thickness of speech that made his every utterance a mini-event. (Forty-five years after the fact, I still find myself referencing his Ben Stokes from

Dark Shadows whenever I talk about “mmmmy worrrrrrrrrrkkkk…”) But Frid was the staked heart and vaporous soul of that seminal horror soap, embodying everything that was great and terrible about it all in one iconic presence. His Barnabas Collins was, improbably, one of the great tragic vampire characters in pop culture, primarily because Frid knew how to let us in on Collins’ pain and empathize with it; he managed the balance between seductive appeal and moral repellence with welcome grace. Unfortunately, he was also often at sea as an actor. The show was shot live to tape, usually in one take, and frequently Frid’s eyes would dart with desperation toward the cue cards. (David Edelstein, in his review of this past summer’s

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark wrote: “…

Dark Shadows scared me, although mostly because Jonathan Frid could never remember his lines and the pauses were hair-raising.”) He was a much more solid presence in the theatrical feature

House of Dark Shadows and its sequel

Night of Dark Shadows, where he knew that there was at least a budget that would allow for a second pass. I look forward to Tim Burton’s take on

Dark Shadows, but it will likely never replace the original chills of the TV series, most of them generated primarily by

Jonathan Frid.4) Name the one horror movie you need to see that has so far eluded you.

“Need to see” is a loaded phrase, but since I’m the one who loaded it I have little choice but to bite. The horror movie that I most “need to see” which has, despite two chances to experience it theatrically in the past three years, continued to elude me is Eugenio Martin’s

Horror Express (1973). Fortunately, the movie is slated for a splashy

blu-ray release on November 29, so hopefully I won’t have that “need” for much longer.

5) Favorite film director most closely associated with the horror genre.

I haven’t seen as much Bava as I’d like (

Blood and Black Lace would be an excellent fall-back answer to question #4); I don’t much care for the Lucio Fulci I have seen (though I’d go to bat for

Don’t Torture a Duckling any day); and though he has made some of my favorite suspense/horror movies--

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Cat o’ Nine Tails, Suspiria and especially

Opera among them—Dario Argento’s output is just too inconsistent and voluminous (I haven’t seen but a fraction of his filmography) to make him a serious candidate. So I’ll have to join the ranks of several respondents here and name

David Cronenberg as my favorite director associated with horror, though he hasn’t made anything like a straight horror movie since 1986-- unless you count

eXistenZ which, to my mind anyway, has more to do with

Naked Lunch (or

Videodrome) than with

Rabid. Cronenberg’s body horror oeuvre was always about muddying the waters between horror and science fiction too, but we can pick that nit another time. Cronenberg it is.

6) Ingrid Pitt or Barbara Steele? Barbara Steele

Barbara Steele has one of the great faces not only of horror movies (especially when punctured by an iron maiden), but of the movies, period. Her standing as a horror cult icon would be cemented by

Black Sunday alone, but I came by my appreciation of her as an adult armed with the knowledge of what she’s done and her impact on the genre. Between the two women, there’s really no contest for me: it’s got to be

Ingrid Pitt, who was an object of this young boy’s fixation with the erotic aspect of horror from the first time I ever saw a still from

The Vampire Lovers up until and beyond her death not quite a year ago. Boris Karloff and Forrest J. Ackerman and Jack Arnold explained to me why horror was for boys, but Pitt made this boy reluctant to wake up from his nightmares, and she made a very good case for a man’s interest in the creatures of the night too. Steele did too, but for me Pitt did it first, and best.

7) Favorite 50’s sci-fi/horror creature.

It may have more to do with my affinity for the movie, but the first thing that came to mind for this category is the rather imposing looking beast from

It! The Terror from Beyond Space, and after a few minutes thinking about it I can’t think of one that scared me more. Ricou Browning’s Creature is the icon, but It! is the shit.

8) Favorite/best sequel to an established horror classic.

Well, I think the answer most on everyone’s mind to answer the “best” part of the formulation is probably the right answer, and that would be

The Bride of Frankenstein. But we quiz takers have also been granted the option to answer in terms of “favorite,” and although

Bride would certainly be in the conversation in that category too, I have to admit that the last few years have made a very comfortable and secure place for

Seed of Chucky to reign in my estimation for this category. (I also like

Alien 3 and

Psycho II a lot.)

9) Name a sequel in a horror series which clearly signaled that the once-vital franchise had run out of gas.

Oh, the choices! I seriously can’t remember even a frame of any Freddy movie past

Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, so I suppose the fourth one, whatever the hell it was called, might be a good candidate. (However, just three pictures later

Wes Craven's New Nightmare proved that there was something left in the tank after all.)

Friday the 13th was running on the fumes of other, better movies to begin with, so I won’t bother there. And I know this will be regarded as heresy, but I’m not sure I even hold

Halloween itself in very high regard these days, to say nothing (and I mean nothing) about its many redundant follow-ups. (I might give

Halloween III: Season of the Witch points for at least

not being about the Shape Otherwise Known as Michael Meyers.) So let’s go to a series that actually meant something to me—I call out Peter Sasdy’s

Taste the Blood of Dracula as the first signal that Hammer’s take on Dracula was getting wobbly. I actually like Roy Ward Baker’s

Scars of Dracula, with its amplified gore and cleavage quotient, which was released a mere six months after

Taste in both the U.K. and the U.S., near the end of 1970. But even this Hammer fan had little patience for Alan Gibson’s lackluster

Dracula A.D. 1972, which in my 13-year-old eyes became the final nail in Christopher Lee’s coffin as far as Dracula was concerned. I’ve never had much desire to revisit

Dracula A.D. 1972 or

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973; also directed by Gibson) since the first and only times I saw them nearly 40 years ago.

10) John Carradine or Lon Chaney Jr.?

“They gotta burn!!!!” John Carradine’s immortal reading of that line in

The Howling is quite literally unforgettable, and I’m glad for it. But so is Lon Chaney Jr.’s sleepy, sad-sack presence as Larry Talbot in the Universal Wolfman series. (My best friend Bruce Lundy a.k.a. Blaaagh ‘round these parts does a devastatingly funny Chaney impersonation.) Neither of the actors represents any particular kind of zenith in the horror genre for me. Both made plenty of bad ones (

Billy the Kid vs. Dracula or

Indestructible Man, anyone?), yet both had long careers as Hollywood utility players in just about every genre of movie except maybe the musical. So my totally random choice, based on the fact that he shared screen time with Maria Ouspenskaya, is

Lon Chaney Jr. 11) What was the last horror movie you saw in a theater? On DVD or Blu-ray?

Theatrically: Joe Cornish’s

Attack the Block (2011), a wonderful mash-up of

Night of the Comet-style sci-fi and Stephen Frears-style social commentary (

Sammy and Rosie Meet the Monsters?)

DVD:

Tales from the Crypt (1972), a personal favorite, a

Horror Dads Halloween pick and my daughter Nonie’s go-to Halloween viewing choice this year. Good girl!

DVR:

Strait-Jacket (1964) As a friend of mine suggested, this is Joan Crawford looking into her crystal ball and channeling Faye Dunaway’s brutal impersonation, which was still 17 years away, into a William Castle-directed

Psycho knock-off (written by Robert Bloch) in which the big reveal is apparent about six minutes in. Not enough style to cover up with dead spots between relatively gory decapitations, just the spectacle of a Hollywood great trying to make a silk purse out of a pretty thin sow’s ear with a very sharp ax. And to think,

Trog was still waiting in the wings. The best thing about

Strait-Jacket comes after the end credits:

12) Best foreign-language fiend/monster.

12) Best foreign-language fiend/monster.

Someone has already mentioned Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu as Raymond Lemorne in George Sluzier’s original 1988 Dutch version of

The Vanishing (Spoorloos), and I think even the titular and quite awesome nasty from Joon-ho Bong’s

The Host (2006), both of which popped on my radar when I wrote this question. But the more I thought about it, if I was going for giant monsters I’d probably have to put Ghidrah ahead of his South Korean cousin, and if Donnadieu’s existential pervert is great (and he is), then in acknowledging one of his primary sources I’d find myself landing on the true answer, which has to be Peter Lorre as the miserable miscreant Hans Beckert in Fritz Lang’s

M.

13) Favorite Mario Bava movie. Black Sunday

Black Sunday (1960) on a rainy day or otherwise inclement day. For the sunnier times, I default to

A Bay of Blood (1971; a.k.a.

Twitch of the Death Nerve). I also have a major soft spot for

Planet of the Vampires (1965). My favorite non-horror Mario Bava? A tie between the delirious

Danger: Diabolik (1968) and the thrillingly silly

Four Times That Night (1972), featuring an extraordinarily lovely Daniela Giordano.

14) Favorite horror actor and actress.

Well, I don’t think there can be any doubt that

Peter Cushing is my top pick. Though he had credits like Laurence Olivier’s

Hamlet (1948) and Edward Dmytryk’s

The End of the Affair (1955) already under his belt, it was

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) that really made him, even more so than favorite costar Christopher Lee, the face of Hammer, indeed, the empathic face of a generation’s worth of horror films. His Frankenstein and Van Helsing are indelible creations, but also he appeared as Sherlock Holmes for Hammer, as well as in terrific movies like

Island of Terror, Torture Garden, The Vampire Lovers and

Asylum (and even in a little chamber drama the cognoscenti refer to as

Star Wars). His best, most emotionally challenging work came as the morally ambivalent Gustav Weil, whose rigid religiosity comes under fire by an evil generated from within his own family in

Twins of Evil (1971), and as the doomed Arthur Grimsdyke in

Tales from the Crypt (1972). Both films were made in the wake of the death of Cushing’s wife Helen Beck and are informed by the man’s devastating loss, from which it is said he never fully recovered. And of course his portrayal of Baron Frankenstein in 1969’s

Frankenstein Must be Destroyed remains the definitive, quite unsympathetic, quite powerful realization of that iconic character.

It’s rather more difficult to choose a female counterpart to Peter Cushing’s influence and legacy in the horror genre, because I don’t really think there is one. (I invite any and all submissions pointing out the obvious candidate that I am just not remembering.) The comparison would be, I think, at best unfair to simply say Ingrid Pitt or Barbara Steele, though those might well be the choices to which I would gravitate. If I were to point to a single performance, however, it might just be

Hye-ja Kim as the genre’s most overprotective

Mother (2009), a performance and a movie which seem both too grand and too specific to be described simply as being from the realm of horror, though by the end of the movie that’s the terrain in which they both most definitely reside.

15) Name a great horror director’s least effective movie.

I won’t go the John Carpenter route, despite the many possible candidates in his filmography, because I don’t think of him as a great horror director. A good choice for me might be Mario Bava’s

Baron Blood (1972), which has a neat premise but takes an awfully long time to fulfill it. But ultimately I’ll choose Dario Argento, whose

Mother of Tears (2007) is flat-out asinine, more resembling the work of an Argento parodist than the real thing. Daughter Asia is awful in the lead, and no amount of copious nudity on the part of a tearful, leather-clad Mama Witch can overcome the gasp-inducing, self-serious silliness that this movie, part three of an incoherent trilogy of which

Suspiria was the first installment, doles out like cheap Halloween candy.

16) Grayson Hall or Joan Bennett?

I understand that Bennett probably has the more refined résumé--

The Woman in the Window, Scarlet Street, The Woman on the Beach, Suspiria-- but she always read, especially as Elizabeth Collins Stoddard on

Dark Shadows, as a bit of a cold fish to these eyes (in other words, exactly as she was probably intended). On the other hand, Grayson Hall, as Dr. Julia Hoffman, Barnabas Collins’ reluctantly sympathetic consort, was brittle, anxiety-ridden, perpetually on the brink of apoplexy, and therefore a much more compelling counter to Bennett’s relatively static presence in the halls of Collinwood. Reader David Robson writes of Hall in his

Dr. Phibes quiz answers: “There's a scene toward the end of the first Barnabas arc where Julia is beset by low-tech, ghostly visions. It's basically Grayson Hall just riding a fucking crazy train - for ten glorious, unbroken minutes, the only thing you saw on ABC was Grayson Hall losing her shit. I would LOVE to have been in the studio the day that scene was shot.”Whenever I hear the

trumpet stings soaring like ravens above the eerie calm before the gathering storm of Robert Cobert’s

Dark Shadows musical score, for some reason I always think first of Hall over the entirety of the series’ vampires, witches and werewolves. Add to that the bit of info gleaned from IMDb that Hall was “known for sometimes outré performances on Broadway” and you get the sum of an endorsement from me. Advantage:

Grayson Hall.

17) When did you realize that you were a fan of the horror genre? And if you’re not, when did you realize you weren’t?

No moment of epiphany to speak of here because it honestly seems like I always was a horror fan. My earliest memories of fear associated with horror or suspense come mostly from TV—being terrified by a guy named Ray who used to be a recurring character on

General Hospital when I was about age 4; a vivid memory of a gigantic seaweed creature enveloping the

Seaview in its deadly tendrils on

Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea from around the same time; a kids’ game show (I was about five, I’d guess) called

Shenanigans which often had contestants entering a dark “haunted house” and having to

snatch a prize from the clutches of a very scary-looking monster. I also remember seeing

The Jungle Book when it was first released (1967) and being frozen in my tracks on the way back from the concession stand by the frightening trailer for

Wait Until Dark. (Way to program previews for appropriate audiences, Tower Theater, Roseville, California!) But it was probably getting hooked on

Dark Shadows when I was about seven years old that really cemented my fascination with monsters and the horror genre. My first issue of

Famous Monsters of Filmland was only a year or so away…

18) Favorite Bert I. Gordon (B.I.G.) movie.

It just has to be

Village of the Giants. I first saw it back in 2005 during a semi-drunken weekend of movie viewing with my best friend, and it really made an impression. Here’s what I wrote about it for

SLIFR way back then:

“Gordon is the distinctive auteur of the "things get real big and go on a rampage" school of science fiction-- from the early '50s through the mid '70s he made 11 mostly terrible movies that featured some sort of creature, or creatures, usually made gigantic and very angry by ill-advised scientific tinkering or atomic-age disaster. His

The Amazing Colossal Man and its sequel,

War of the Colossal Beast, are iconic science fiction cheapies, excellent encapsulations of the ups and downs of a very prevalent theme in B-movie science fiction of the time. The director usually wrote his own scripts, often in collaboration with others, and the

Colossal pictures were no exception. But Gordon, along with co-screenwriter Alan Caillou, would go to the well of a very different science fiction master for inspiration when it came time to craft this 1965 masterpiece of young hoodlums who grow to be 30 feet tall and become no less the authority-flaunting thrill-seekers for it. Yes, the hep cats frugging in strange fringed bikinis and furry swim shorts behind the opening credits of

Village of the Giants may be the swingin'-est thing happening during this sequence, but it's by no means the strangest. No, that status goes to the moment when this credit pops on screen over all that frugging and wild surf music: "Based on the Novel

The Food of the Gods by H.G. Wells" !!! At that moment it ought to have been pretty damn clear that we're not in for Merchant/Ivory-esque tortured fidelity to the original text with this particular literary adaptation, though for Gordon Wells' novel clearly was a major work-- he would "adapt" it again in 1976 for American International Pictures, this time calling it

The Food of the Gods and focusing exclusively on giant rats, chickens, et al, leaving the juvenile delinquent populace to frug (or whatever we juvenile delinquents did in the mid '70s-- I forget) at their normal size.

The opening credits are followed by a scene of unleashed carnality so astonishing that I was forced to put down my cheese sandwich and put off further chewing until after it was finished. The camera pans over to a wrecked car that's been run up on an embankment just before the cameras rolled (Mr. Gordon was, as you may have guessed, a budget-conscious filmmaker fond of such shorthand imagery). Inside are six teens, three guys, three girls, and as they stumble out of the wreckage it becomes clear that they are not, as you or I might be, stunned in the aftermath of a car crack-up, but instead somehow turned on by it. They're downright giddy, in fact, and contemplate hoofing it to the nearest burg so they can channel their energy into further wild adventures traveling around the countryside causing trouble for various locals. And then, before they start easing down the road, a couple of the chicks start dancing, man, in that insinuating way that seems strangely familiar, kinda like what we saw under the opening credits, and before you know it they've got the guys shimmying like it's a roadside edition of

American Bandstand, and everything's getting wilder and wilder... and that's when they start rolling around in the mud and tossing great huge clumps of it at each other in the wildest pre-Jack Valenti scene of barely sublimated orgiastic not-exactly-sex that I can remember ever seeing.

And that's just the first eight minutes. How can the movie ever hope to match or surpass it? Well, the fact of the matter is, it can't, really. But the good news is that it doesn't matter, because

Village of the Giants comes pretty fully loaded with energy, a couple of pretty decent tunes courtesy of the Beau Brummels (and inexplicable musical numbers by some generic crooners that are on the opposite end of the scale from "pretty decent"), plus scene after scene of enlarged creatures (a pooch, a duck and a common household tarantula, for starters) attacking or otherwise interacting with a dazzlingly unimpressed citizenry. Gordon isn’t interested in any highfalutin existential ideas that might steer this romp toward becoming a reverse of Jack Arnold and Richard Matheson’s

The Incredible Shrinking Man. As the SCTV film critics might have said, he just likes to see things blow up real big.

Then there’s the cast. That’s bombshell Joy Harmon and co-bombshell Tisha Sterling as the two JD babes, Mickey Rooney’s son Tim as another of these teenage blights on society, and Beau Bridges, supremely blissed out in that Dennis Wilson-warm-California-sun kind of way as the leader of the pack. Just imagine how formidable these ruffians become when they ingest the mysterious “goop” concocted by the precocious “Genius” (essayed by little Ronny Howard, in a characterization remarkably similar to that of his indelible Opie), which causes them all to become 30 feet tall and drunk with their newfound power over the law (and all the weaklings they used to lord it over anyway). But that’s not all. “Genius” has an older sister, Nancy (generically appealing good girl Charla Doherty), whose boyfriend Mike (ex-Disney icon Tommy Kirk) heads the resistance against these ginormous bullies, with help from best buddy Horsey (

The Rifleman’s own Johnny Crawford), bohemian babe Red (soon-to-be-famous choreographer and ‘80s one-hit wonder Toni Basil) and the local sheriff (played by Tyrell Corporation CEO and Overlook bartender Joe Turkel). And prefiguring a career of attaching himself to his son’s projects, there’s even a brief appearance by Rance Howard, though I can’t for the life of me remember in what context he appears. When all these folks gather for a community picnic, the main course of which is the aforementioned giant duck, skinned and roasting on a spit smack in the middle of the town square, I turned to Bruce and proclaimed that

Village of the Giants could end right now and still be the automatic winner of Most Unabashedly Fun Movie of the Weekend in my mind.

The movie is full of obvious and on-the-cheap optical effects employed to grant the newly gigantic beings their oversized grandeur. And one in-camera trick, a sneaky perspective shift that tricks you into thinking you’re actually seeing the teen giants growing (and then shrinking) is actually pretty resourceful and effective—it’s a low-tech harbinger of that shot in

Jaws, and so many subsequent thrillers, where foreground and background move in opposite directions along the Z-axis, creating a dolly effect with no actual camera movement that leaves the subject of the shot queasily adrift in the middle of the frame.

But no special effect or trick shot in

Village of the Giants ends up having half the impact of Tommy Kirk’s hairdo, a wildly elevated ducktail that exposes the aging teen star’s hairline impairment and retreats from his eerily appropriate duck-like facial features to such a degree that I began to irrationally (perhaps it was the hour—there was no tequila imbibed this night) suspect that some unholy alliance of the movie’s hairdresser and his own body had conspired to make the actor look as smarmy and

Anatidaen as possible. This graphical connection between the “teen warrior” (no surprise that Kirk was actually 24 when the movie was filmed) and his oversized foes—especially that big quacker—lend his sleepy-eyed battles a fuzzy sense of familiar set against familiar—you know, like a cockfight, only with mad ducks. (Maybe I did have something to drink after all…)”

19) Name an obscure horror favorite that you wish more people knew about.

I’m not convinced that either of them are exactly

obscure, but far more than just we horror geeks should know of both

Ravenous (1999), director Antonia Bird’s gonzo riff on the Donner Party, and Gary Sherman’s literally underground thriller

Raw Meat (1972; a.k.a.

Death Line). These are two movies that give cannibalism a very good name—just don’t try it at home, kids.

20) The Human Centipede-- yes or no?No, thanks.

20) The Human Centipede-- yes or no?No, thanks. If only Tom Six were as smart and/or talented as he thinks he is. Unfortunately, he’s just cynical. And not so smart.

21) And while we’re in the neighborhood, is there a horror film you can think of that you felt “went too far”?

Well, logic would dictate that

The Human Centipede would be the natural choice here. But ironically, I actually don’t think it goes too far, in the sense that it is outrageously banal and, as I suggested in the piece linked above, the director plays his most outrageous cards rather coyly. He isn’t at all wise or intuitive enough to figure out a way to turn his juvenile scatological fantasies of violation and degradation into something even remotely close to the most grandiose claims of the movie’s supporters. My candidate would be Takashi Miike’s notorious “banned from cable” episode of the “Masters of Horror” series entitled

Imprint (2006). I happen to be among those who think Miike’s

Audition is a genuinely great movie, and it’s no stroll in the park, even for someone who has seen an awful lot of grisly things in horror films and every other sort. But

Imprint struck me as a terrible wallow in truly ghastly images of torture and violation of the body. It only runs about an hour, but that’s enough time for Miike to cross the line more than once in this tale of a man (Billy Drago, truly awful) who visits a brothel and spends the night in the company of a disfigured woman whose tragic tale of her own history gets worse as the man prods more secrets from her than she is initially willing to reveal. This is the sort of cinematic provocation—yes, Miike is a

very bad boy-- that can seem shallow and tiresome in something like

Ichi the Killer. But here Miike accesses real pain; unfortunately, it’s not in service of much beyond testing the audience’s limits for scenes of needles being driven under a woman’s fingernails and into her gums, not to mention the recurring motif of hideously aborted fetuses. My own personal experience with the loss of my son 14 years ago may not make me the ideal audience for

Imprint, but if there is such a thing I’m not sure who it might be.

22) Name a film that is technically outside the horror genre that you might still feel comfortable describing as a horror film.

If it’s not demeaning to suggest it, I’d nominate

Taxi to the Dark Side. But if we’re limiting ourselves to fiction film, then

Salo: The 120 Days of Sodom seems a good choice. I also found

Beverly Hills Chihuahua downright bone-chilling.

23) Lara Parker or Kathryn Leigh Scott?

I think this is the first “either/or” comparison in the history of these quizzes in which 100% of the vote (so far) has gone to one subject over the other. But, unlike my preference for underdog Grayson Hall over favorite Joan Bennett, I cannot, out of sincerity or perversity, swim against the tide this time. I liked Kathryn Leigh Scott’s Josette duPres on

Dark Shadows just fine-- Scott played Barnabas’s long-dead lover and her reincarnation, Maggie Evans Collins. But the young boys gravitate to the luscious bad woman almost every time, and

Lara Parker’s petulant, seductive Angelique, Barnabas’s tormentor down through the centuries, was sex incarnate for those of us who hadn’t quite figured out what sex was yet. Parker was fun to watch, impossible

not to watch, as all grand villains should be. And, as has been pointed out more than once already here, she was in

Race with the Devil (1975). Case closed.

24) If you’re a horror fan, at some point in your past your dad, grandmother, teacher or some other disgusted figure of authority probably wagged her/his finger at you and said, “Why do you insist on reading/watching all this morbid monster/horror junk?” How did you reply? And if that reply fell short somehow, how would you have liked to have replied?

The disdain I felt from many of the adults surrounding me regarding my love for horror movies was often inseparable from the disdain over my passion for movies in general. Such devotion to what was viewed essentially as disposable entertainment was not comprehensible to the more practical-minded adults that lived in my hometown. (The one glorious exception was my

Grandma Rina.) And most flatly disapproved of my interest in horror and science fiction—I remember my dad blowing his top at me once when he overheard me describing the blood rushing from the elevators in

The Shining to a younger cousin, as if I were force-feeding the kid mental rat poison. Back then I couldn’t have, and didn’t, articulate exactly why I loved the monsters—I just knew that I enjoyed the vicarious thrill, the sense of being temporarily unsettled that often came with trips into the mindscapes these movies conjured. Later I would see how horror movies could often go beyond simple jolts and shivers, how the genre could be adapted for all kinds of metaphoric and subtextual use. But when I first loved horror movies, it was enough for me to know that they were for a certain kind of viewer only, and being that certain kind of viewer made me part of a club, a club whose members all understood without having to explain it to anyone, least of all themselves, why such frightening stories and imagery made them so unaccountably happy. So often, before I made friends later in adolescence who shared my passion, horror movies felt like movies made just for me. And I liked them because I liked them.

25) Name the critic or Web site you most enjoy reading on the subject of the horror genre.

Though I have been accused of including this question in order to troll for praise (facetiously, I hope!), I don’t particularly think of myself as particularly well-versed or experienced in the genre, and I certainly don’t think of myself as an expert writer about it. No, for the kind of intelligent expertise I enjoy when reading about horror movies only one source I’ve discovered has been able to fill the bill for scholarship and smart writing:

Arbogast On Film. I need not say more. If you’re a horror fan and you don’t know this site, you should get familiar, and quickly. As for spending time in the company of great fellas who also happen to be articulate lovers of the genre and parents who hope to raise similarly devoted chillun, it has been a great pleasure and privilege to be part of the occasional gathering of the

Horror Dads over at TCM’s

Movie Morlocks. Richard, Greg, Jeff, Paul and Nicholas all know a

hell of a lot more about horror than this self-professed

Famous Monsters lifer could ever claim to know, and I enjoy their friendship and their fertile brains (chilled, with garnish) more than I can express.

26) Most frightening image you’ve ever taken away from a horror movie.There are many, of course, but this one, one of several in this movie alone, is for the ages. Grown men will weep and gnash their teeth. I know, because I was one of them while I was watching

Audition for the first time.

And this one has to count because I had nightmares about it before I ever even saw the movie.

27) Your favorite memory associated with watching a horror movie.

27) Your favorite memory associated with watching a horror movie.Again, many to choose from, but my favorite, primarily for the way it plunged me back into a state of irrational terror that I hadn’t felt since I was a much younger child, came courtesy of George A. Romero’s

Night of the Living Dead. I had caught the movie a couple of times—perhaps uncut, probably not—on late-night weekend

Sinister Cinema broadcasts out of Portland, but I had never seen it projected. So one Saturday night during our sophomore year at the University of Oregon best-pal Bruce and I drove out to a cineplex on the western outskirts of town where they were showing

NOTLD at midnight. The place was packed and the crowd, though certainly up for a good time, wasn’t excessively rowdy—we all settled in to the movie’s bleak apocalyptic vibe with little effort.

And about 15 minutes in, about the time poor, unfortunate Barbara (Judith O’Dea) and poor, unfortunate Ben (Duane Jones) start boarding up the doors and windows of that dilapidated house, some kid who obviously either couldn’t afford a ticket or was determined by the management to be too drunk to let in through the box office started shouting and banging on the exit door near the bottom of the screen from outside. This went on for several minutes, but rather than take it as an intrusion the audience seemed to dig the extra frisson of dread the would-be intruder was adding to the show, their general whatever vibe no doubt attributable to adventures in weed that they may or may not have indulged in before the movie started. In fact, Bruce and I were probably one of the few people in attendance not chemically enhanced in some way, yet for some reason I took on the paranoid characteristics of a dissolute hophead and began my own personal freak-out. The movie was getting to me all on its own, and now here’s this guy outside banging on the door, yelling incoherently. He could be a zombie. Yeah, he probably is! Jesus Christ! STOP IT, MAN!!!!! JUST STOP IT!!!!!!!

Sure enough, the banging stopped after a few minutes and we were left with only the movie to scare us out of our wits. And how it did. Even though I had seen it before, the movie went about the business of rattling the audience in that special way familiar to anyone who has already survived seeing it. But the guy outside got to me, and for the duration of the show, while the house was being besieged by the flesh-eating undead, I kept coming back to that bastard outside. What if the movie ended and we all shuffled out into a world where there’s hundreds of these goddamned soulless beasts between us and our cars, just waiting to tear us limb from limb or, worse, offer us up a simple flesh wound that would ignite our own lust for bloody and unwilling long pig? By the time the movie ended, I was driven into such an irrational fear, sparked by the movie and the special interactive fun that took place during the screening, that I actually cringed as we passed through the exit door, into the lobby and out into the parking lot. Which was curiously zombie-free. To this day I don’t know if I was purely relieved or if perhaps some part of me was slightly disappointed. Whatever it was, thanks for the memory to George A. Romero and especially to that poor besotted door-banging interloper, whoever you are!

28) What would you say is the most important/significant horror movie of the past 20 years (1992-2012)? Why?

It might be

Audition (1999), simply because Takashi Miike’s movie crystallized the artistic value of extreme violence in a horror context and made way for countless imitators, from Japan, South Korea and, of course, the United States, many of whom frequently made the mistake of assuming that the gore was the point (a misstep also often taken by Miike himself in his prolific career). Several of the movies that have come in this one’s wake which have taken advantage of the boundaries Miike pushes here, movies that are themselves simply an excuse for an onslaught of violence, tend to forget that for the first hour

Audition resembles an earnest relationship picture rather than a horror film… which is why it is so profoundly unsettling when Miike finally yanks the rug out from underneath us. For me

Audition is significant not only for the ways it uses violent imagery, but for the way in which it has managed to prove that doing visceral horror right depends a lot more on the brains and intuition of the filmmaker than it does the proficiency and expertise of the effects houses.

29) Favorite Dr. Phibes curse (from either film).

I like Phibes’ elaborate interpretation of the Curse of the Firstborn that ends the movie, but my favorite is actually the Curse of the Locusts, from the boiling of Brussells sprouts, to the laying down of the map approximating the nurse’s position in bed, the close-ups of the drill going through the floor, the green goo sliding through the tube stuck through the floor/ceiling and dripping onto the nurse and the furniture in her bedroom one floor below…

the locusts being fed through a larger tube which also penetrates the floor/ceiling…

and the final result.

30) You are programming an all-night Halloween horror-thon for your favorite old movie palace. What five movies make up your schedule?The

Horror Dads did this subject up right for Halloween, but we only got to pick one movie each for our fest. Here’s what I’d choose if I programmed all five pictures myself, in the order in which they would be shown:

Those oughta keep you awake all night. And just

try sleeping afterward...

*****************************************

POSTSCRIPT: Behold Satan and Daughter of Satan, the winners of the New Beverly Cinema Halloween Costume Contest! Best Halloween ever? Just maybe!

*****************************************

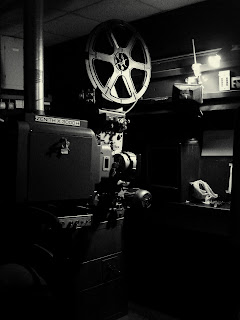

And that progress does indeed march on. As Jen Yamato reported in her piece for Movieline on the downshift in 35mm print production, studios like 20th Century Fox have already begun movement in some Asian markets to phase out distribution of 35mm prints to theaters in favor of an all-digital exhibition format. She quotes Fox International’s Sunder Kimatrai as having said, back in August of this year, that “the entire Asia-Pacific region has been rapidly deploying digital cinema systems” and that “over the next two years we expect to be announcing additional markets where supply of 35mm will be phased out.” And if that isn’t convincing enough, John Filian, president of the National Association of Theater Owners, had this rather definitive statement to deliver in his annual state of the industry address to attendees of Cinecom, NATO’s inaugural convention gathering in Las Vegas back in March 2011:

And that progress does indeed march on. As Jen Yamato reported in her piece for Movieline on the downshift in 35mm print production, studios like 20th Century Fox have already begun movement in some Asian markets to phase out distribution of 35mm prints to theaters in favor of an all-digital exhibition format. She quotes Fox International’s Sunder Kimatrai as having said, back in August of this year, that “the entire Asia-Pacific region has been rapidly deploying digital cinema systems” and that “over the next two years we expect to be announcing additional markets where supply of 35mm will be phased out.” And if that isn’t convincing enough, John Filian, president of the National Association of Theater Owners, had this rather definitive statement to deliver in his annual state of the industry address to attendees of Cinecom, NATO’s inaugural convention gathering in Las Vegas back in March 2011:

Not everyone is convinced that going digital is necessarily all that bad an idea however. Friends and acquaintances of mine who live in small-to-medium-sized markets outside of major cities in California and New York, where the issue of revival cinema is moot, are pleased as punch to see the spiffy, bright, crud-free imagery that conversion to digital brings to their stadium-seating-style multiplexes, and to the crappy cracker-box cinemas that have limped along without much change since the ‘80s. (Whether they remain equally pleased by the same 10-15 movies that will be available at these mainstream movie houses is another question, one with which most moviegoers are well familiar.) But even some who have access to great revival programs like those available in Los Angeles and Austin, Texas are unconvinced that the potential loss of 35mm exhibition is all that significant. Yamato’s piece inspired several passionate comments, like this one from “Sunnydaze”:

Not everyone is convinced that going digital is necessarily all that bad an idea however. Friends and acquaintances of mine who live in small-to-medium-sized markets outside of major cities in California and New York, where the issue of revival cinema is moot, are pleased as punch to see the spiffy, bright, crud-free imagery that conversion to digital brings to their stadium-seating-style multiplexes, and to the crappy cracker-box cinemas that have limped along without much change since the ‘80s. (Whether they remain equally pleased by the same 10-15 movies that will be available at these mainstream movie houses is another question, one with which most moviegoers are well familiar.) But even some who have access to great revival programs like those available in Los Angeles and Austin, Texas are unconvinced that the potential loss of 35mm exhibition is all that significant. Yamato’s piece inspired several passionate comments, like this one from “Sunnydaze”:  In fact, the most potent outcry is one that is based not on aesthetic preference but on preservation of cinema history, and there is no compelling reason why art and commerce need necessarily be at odds here. Reader Ant Timpson points out that there even seems to be little economic sense for studios to resist continuing to strike archival prints designated specifically for revival programming. “They'd make their money back within the first 20 bookings,” Timpson argues, not to mention holding cultural value in the cause for preservation. But it’s no comfort for film fans if it’s left up to almighty market demand instead of historical or artistic worth to determine which titles the studios deem worthy of preserving on 35mm, from where shall come further digital copies. Only the titles that have been determined to be the most commercially viable are likely to be available in digital formats, thus limiting what can be shown in cinemas and exposed to future generations. For these films to mean anything to anyone down the road, is it not crucial that people be able to at least have the option to see them in environments considerably more enveloping, and less distracting, than their living rooms or on airplanes? Comparing the dollars-and-cents cost of actual preservation to the cost of the loss of these films in terms of cultural heritage, it seems that one is (or ought to be) far more heavily weighted than the other.

In fact, the most potent outcry is one that is based not on aesthetic preference but on preservation of cinema history, and there is no compelling reason why art and commerce need necessarily be at odds here. Reader Ant Timpson points out that there even seems to be little economic sense for studios to resist continuing to strike archival prints designated specifically for revival programming. “They'd make their money back within the first 20 bookings,” Timpson argues, not to mention holding cultural value in the cause for preservation. But it’s no comfort for film fans if it’s left up to almighty market demand instead of historical or artistic worth to determine which titles the studios deem worthy of preserving on 35mm, from where shall come further digital copies. Only the titles that have been determined to be the most commercially viable are likely to be available in digital formats, thus limiting what can be shown in cinemas and exposed to future generations. For these films to mean anything to anyone down the road, is it not crucial that people be able to at least have the option to see them in environments considerably more enveloping, and less distracting, than their living rooms or on airplanes? Comparing the dollars-and-cents cost of actual preservation to the cost of the loss of these films in terms of cultural heritage, it seems that one is (or ought to be) far more heavily weighted than the other.