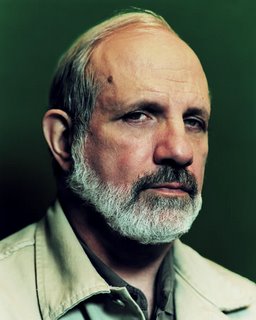

(This consideration of Brian De Palma’s latest film,

The Black Dahlia, discusses the film under the assumption that readers will already be familiar with the plot twists and turns of the movie. Therefore, a

SPOILER WARNING is in full effect.)

Brian De Palma’s film of James Ellroy’s

The Black Dahlia, a fictionalized account of the notorious and ghastly murder of would-be starlet Elizabeth Short that has, for 60 years, haunted Hollywood and gone unsolved, is positioned to become the year’s most polarizing movie, and not just for the general movie-going public, most of whom seem either dissatisfied with it as a film upon seeing it or, if box office numbers can indicate anything, indifferent to it being in the marketplace at all. No, where

The Black Dahlia seems to be most divisive is among the legion of film critics and fans who have taken to De Palma in a most personal way, who have gone to great lengths and endured many arguments in championing him as a singular film artist over the 40-some years he has been directing movies. For some, De Palma’s new film is a key work, one artist’s fundamental understanding of another artist (Ellroy) who is often tarred with the same accusations of being a misogynist, a misanthropist, a harsh and unfeeling style-over-substance provocateur.

The Black Dahlia is also important, for these viewers, as an emotional and intellectual summing-up, a complete rethinking of De Palma’s motives, his aesthetic, his entire rationale as a filmmaker. For others, the movie is a failure of narrative and the director’s ability to imbue style with meaning, to use it creatively as a truly expressive element of his idiosyncratic approach to narrative cinema. Those in this camp who are familiar with the book have also leveled charges that De Palma’s movie is fundamentally a failure of adaptation, one that telescopes the background and motivations of the main characters in the book to an almost abstract level, draining them of any possibility of existing as compelling individuals in an artistic framework for whom the audience could feel any emotional connection.

The best place to track the respectful back and forth of ideas about the merits (or lack thereof) of De Palma’s film is in the comments thread under Matt Zoller Seitz’s poetic, impassioned and evocative

review, perhaps the most perceptive defense of the movie in essay form there may be floating out there right now. Matt’s assessment of how he perceives that the film works and how De Palma subtly changes the meaning of some of his familiar stylistic devices is eye-opening—for example, Matt convincingly tracks the transformation of De Palma’s signature point-of-view shot as no longer representative of a detached, God-like stance, but instead, as employed in the sequence in which Short’s body is first discovered, an embodiment of the interior conflict and grief at the center of the lead character, played by Josh Hartnett, who will soon become obsessed with Short and her past. The connection between De Palma’s style, often used by his detractors as a club to beat the director over the head with accusations of empty gimmickry over “substance,” and the film’s subject matter-- a man trying to discover and maintain his moral compass in the foreground of a corrupt social system that continually causes the ground under his feet to shift like quicksand-- is fruitfully extrapolated here to suggest how

The Black Dahlia puts the lie to one of the most familiar of charges against De Palma:

”Most striking of all is De Palma’s use of composition and camera movement to suggest the right moral response to savagery. In two scenes involving Short’s corpse—its discovery by the L.A.P.D. and a subsequent coroner’s report—Zsigmond gracefully cranes down from a loftily detached position (a God’s eye view) to a subjective one (Short’s P.O.V., looking up at the men scrutinizing her ravaged body). In the space of seconds, we go from objectifying Short to feeling for her—the hero’s moral evolution in microcosm. That any attentive viewer could sit through this film—or its spiritual sister, Casualties of War-- and still think De Palma hates women is inconceivable.”Matt’s analysis of De Palma’s methodology, his work as a film artist, and his attempts to use

The Black Dahlia as an occasion to reframe his career and perform a major work of film criticism directed at his own prodigious output, is almost overwhelming in its thoroughness and its ability to track clearly through some fairly knotty aesthetic terrain. And it’s convincing too, something that can’t be claimed for the bet-hedging tangle of reactionary compare-and-contrast rhetoric that comprises Armond White’s

review, a piece which typically implies that any disagreement, even with a quite reserved endorsement that boils down to “they can’t all be home runs,” is proof of the viewer’s compromised integrity or lack of perception.

At the same time, Matt is no bully, and he concedes that his position on the film is in the extreme minority. But this is not his way of shrugging and saying, “Maybe I’m wrong; maybe I’m right;” he never shies away from the obvious fact that there is room for disagreement, for not seeing the complexities that he does in precisely the way that he sees them, while unflaggingly standing up for his vision of the film. His non-antagonistic stance creates an atmosphere where disagreements can be freely aired, and aired they are. The most vocal dissenter so far is probably That Little Round-headed Boy, whose enthusiasm for De Palma on his

eponymous blog has been well noted in the blogosphere of late. (Most recently, he even defended

Scarface.) TLRHB’s objections are largely rooted in what he sees as missteps in De Palma and screenwriter Josh Friedman’s adaptation of Ellroy’s complex novel, particularly the decision to have Josh Hartnett’s Bucky coolly dispatch Swank’s spider woman at the end of the film, rather than let her rot in the fetid, corrupt lifestyle perpetuated by her family. But his complaints also extend to the casting. He finds Scarlet Johanssen’s performance, as the icy blonde noir dame with a mysterious past who forms the third point of the platonic triangle who also includes Hartnett and Aaron Eckhart’s obsessed detectives, stiff and too obviously, self-consciously iconic, but feels she finally thaws and comes to work as something more than an aestheticized object. And TLRHB has more profound reservations about Swank, who he feels comes off as a horror film variation on Evelyn Mulwray right out of the gate and never escapes the shallow vampirism at the heart of the character’s concept.

However, he’s bullish on Hartnett as an empathetic protagonist, even though the actor has come in for a lion’s share of criticism regarding his blankness and/or inability to carry off the emotional demands of the role. TLRHB also finds that De Palma adds an unexpected frisson to Short’s audition footage by casting himself as her demeaning, off-screen director, and he has very kind words for Fiona Shaw, perhaps the film’s most obvious lightning rod in terms of gauging whether or not De Palma knew what he was doing with the film’s most tonally jarring set piece-- Hartnett’s introduction to Swank’s corrupt, inbred (metaphorically, if not literally) family over which Shaw holds a ghastly form of court, a fetid, comic microcosm of the ghoulish, moneyed upper classes fouling the roots of the image-based Hollywood picture-making machinery.

TLRHB ends by questioning whether the depth that Matt perceives in the film can be attributed to what Matt brought to the film himself, as a sensitive critic and one well familiar with the psychological complexities of the characters as rendered in Ellroy’s language, complexities that TLRHB insists are not readily apparent on screen. And he also offers a poser which has gone unaddressed by any of the thread’s participants so far: “If Hollywood would actually let De Palma be De Palma, do you think this really would have been his choice of film to make? And are we just overlooking that in praising what he was forced to make to keep working?” Given De Palma’s difficulties in getting his most recent pet project, a thriller known as

Toyer, off the ground, and given that the director’s next announced project is a prequel to one of his biggest hits,

The Untouchables: Capone Rising, it’s a question worth posing. Yet TLRHB himself provides a sort of response when he suggests that, even though he remains disappointed by

The Black Dahlia, he’ll gladly pay to see it again if it contributes to the movie making enough money to allow the director to create another

Femme Fatale.

So, after all this debate over De Palma’s latest film, which comes after weeks of anticipation and revisiting of the director’s filmography on this site as well as many others, on which side of the fence do I find myself? I stayed away from reading any reviews of

The Black Dahlia, including Matt’s (especially Matt’s), until I’d had a chance to experience and digest the movie on my own. (It’s virtually impossible, however, if you wait till almost a week after a major film is released, to remain completely unaware of its general critical reception, and I had posted links to both pans and raves on this site the day before the film came out.) It’s been several days since I’ve seen it and I feel that digestion is still in progress, helped along by all the comments I’ve read since having my own initial reaction. The problem for me is that I’m not finding, as I customarily do with De Palma, that there’s all that much to digest.

The Black Dahlia seems to me an intelligently mounted misfire, one that fails to make its central metaphor, the bisected body of an already degraded and humiliated starlet, who might just as easy have been ground up and spat in two halves from the gaping maw of the Hollywood machine, resonate with the kind of force that might have carried the movie to lofty, expressive heights.

What’s fascinating to me in reading a review like Matt’s, as a self-avowed, but not uncritical or all-forgiving, member of the De Palma camp, is the degree to which it is utterly convincing—that is, a compelling, understandable, no-bullshit analysis of the film from his distinct point of view-- while being so divorced from my own experience and conclusions. Where Matt locates zeal and energy in the formal aspects of

The Black Dahlia that proceed on to artistically engorge the film for him and flush it with meaning, I saw a film that lacked exactly the urgency that he and others have found to be so abundant in it. To my heart and mind,

The Black Dahlia, despite its considerable craft and obvious serious of intent, feels listless, indifferent, and disconnected from the film noir tropes, character conflicts, and even the meticulously reconstructed 1940s-era Los Angeles (shot entirely on sets in Bulgaria) it so tantalizingly recreates. And I think it is possible to recognize that in

The Black Dahlia De Palma could very well be trying, at age 66, to reframe the strategies and conclusions of his entire career. He made a similar summation when he employed the technique he honed so brilliantly in

Sisters, Carrie and

Dressed to Kill to inform the personal paranoia and political outrage at the heart of

Blow Out. The difference is that in

Blow Out the result was an appreciable heightening of De Palma’s abilities to express his personal concerns in filmmaking about and within the thriller form.

The Black Dahlia may involve a process of discovery for De Palma, one which may yet result in another major work that couldn’t have existed without the conscious reevaluation that Matt claims the director is engaging in here. But the film itself has the meandering feel of an artist in search of meaning, rather than one who has discovered it and is putting it to new and exciting use.

The narration, read by Harnett’s Bucky, is very helpful in keeping the viewer oriented within the machinations and narrative switchbacks which undoubtedly find their origin in Ellroy. But the actors never find a way to transcend their stylized appearances and become more than just film noir archetypes, which is the fault of the performers for essentially either not being right for their roles, or the director’s in not being able to tease out the dimensions in their acting that would make his purpose take root in their work and flower artistically on the screen. I can think and read all day and all night about the interior conflict of Bucky’s frustrating attempts to gain a moral understanding that he can live with while being surrounded by so many forces bent on stripping it away, and about De Palma’s strategies to visualize this interior conflict within his formal style, but if all this doesn’t, on some profound level, read on the lead actor’s face or in his movements, his inflections, or in the soul that’s bared on screen, then the movie remains all surface intent and very minor in its successful transformation of that artistic purpose. Unfortunately, Hartnett remains for me a shell of a performer—he goes through the motions well enough to convince the viewer that he’s seen all the key movies, and he’s got enough superficial skill to remain watchable, but when I hear comparisons of what he does in

The Black Dahlia to the empathy John Travolta was able to achieve in

Blow Out, or what Michael J. Fox communicated in

Casualties of War, the lack of responsiveness in Hartnett’s eyes, his boyish, unlived-in face and curiously flat line readings, it makes me feel like there’s a doppelganger film unspooling out there and that’s the one that everyone who loves this movie has seen.

Bucky’s partner, in police work as well as moral decay, is Lee Blanchard, played by Aaron Eckhart, and it’s the first time Eckhart’s natural garrulousness as a performer has not helped him a whit onscreen. Blanchard, who turns out to be central to the movie’s mystery and who knows far more about corruption than even Bucky knows, is the character that must carry the external narrative weight of the obsession with Elizabeth Short that Bucky deals with internally. But at least in the version of Josh Friedman’s script that ended up on screen, Blanchard’s background is so sketchy that the psychological impetus for all of Eckhart’s teeth-gnashing and twisting on the hook the murder has impaled him on remains clouded, and the actor ends up looking foolish. His writhing didn’t inspire the kind of morbid curiosity in this viewer to wondering what was going on, only to speculate that there was something going on that wasn’t being successfully communicated. When Lee’s motivation for his obsession, the horrible death of a sibling, is revealed in a rather offhand manner by his girlfriend, played by the close-to-ossified Scarlet Johannsen (who does very little in this movie that doesn’t seem offhand), the possibility for further empathy with Lee and his torment has been effectively scuttled and one more possibility for Short’s murder to meaningfully inform the movie’s main character concerns falls by the wayside.

Johanssen’s character, Kay, barely exists as anything more than a graphic touchstone to an earlier era anyway. Much has been made of the fact that Hartnett and Johanssen simply seem too young and untarnished to embody the young but world-weary Hollywood denizens on display in De Palma’s (and Ellroy’s) corroded universe. But that would be far less of a concern, for me anyway, if they had more to do than stand around and look world-weary. At least Hartnett is allowed to move through Vilmos Zsigmond’s meticulously crafted frames with a modicum of physical grace, and he is at the center of De Palma’s one show-stopping action set piece (more on that later). Johanssen, on the other hand, is on board for what she brings to the table via her lush sexiness and her ability to carry off a ‘40s coiffure. Her performance can be boiled down to the attributes of the golden, attainable, yet tarnished angel, the idealized hope which Bucky projects onto Short and sees slowly corrode away while watching those audition films, and finally a stag film starring Short which drives home for him the horrors she endured on the road to her loss of innocence and ultimate violation. (Mia Kirshner, it must be said, is extraordinary in this movie, creating a veil of mystery about Short that is all her own, and she made me profoundly wish that De Palma had scuttled all this lifeless dramaturgy and crafted a movie that really was about the Black Dahlia.)

Johanssen’s blonde bombshell exists essentially for what she represents to Bucky, purity stained by evil but wholly redeemable, and the shallow concept turns out to be a deadly role for the actress. There are times she barely seems ambulatory within the lush Panavision confines De Palma traps her in—it may be only a slight exaggeration to report that she spends half the movie posed with her left arm cocked at an angle, unmoving, sporting a cigarette lighter and little notion of what to do with her free appendage, as if she’s auditioning for instant icon status in a movie fashion magazine, Veronica Lake cast in Zsigmond amber. By the time Kay is offered to Bucky in a halo of golden light as the reward for having survived the evil plotting of those behind the Dahlia’s murder, she resembles nothing less than that embodiment of twinkling Aryan inspiration played by Glenn Close who popped up in the stands occasionally to offer inspiration to Robert Redford in the execrable adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s baseball novel

The Natural.

As the movie’s one truly deadly femme fatale, Madeleine Linscott, a luscious gargoyle born of frivolous entitlement and utter boredom, Hilary Swank at least squeezes some juice out of her character before the movie goes completely off the rails. Swank seems as initially miscast as Hartnett and Johanssen—she’s never exactly been the go-to girl when looking for seductive, insinuating feminine rage. She’s introduced to the movie sauntering through a lesbian bar already in full spider-woman mode—the bar features a full-on girl-on-girl production number (vocals courtesy of a tuxedo-clad K.D. Lang) that initially looks like a gender-reversed revival of “The French Mistake” from

Blazing Saddles and registers barely a hiccup on a titillation meter, as does all of the glossed-over sex to come later between Bucky and Linscott, who represents the dark side of the Dahlia that Bucky actually can reach out and touch.

(The movie’s erotic fizzle stands in distinct contrast to the decadent sensual appeal of

Dressed to Kill or

Femme Fatale.) Which isn’t to say that Swank isn’t game; she imbues Madeleine (whose name deliberately evokes Kim Novak in

Vertigo) with a dangerous, attractive, slightly perverse vibe (which will flower fully when we meet her family) that makes for a pretty good defense against those who have knocked on her casting based on her perceived inability to forefront her sexuality and ground it in character. Alternately appealing and appalling, Swank’s Madeleine has also, of course, some of the brute, androgynous vitality of Ann Savage in

Detour, or Audrey Totter, or even Gene Tierney in the luscious Technicolor melodrama

Leave Her to Heaven, where she presides over the drowning of a crippled boy who she believes is taking too much of her husband’s attention away from her. Unfortunately, Swank’s Madeleine is drawn more along the cruder lines of Savage’s portrayal of irrational evil (adding an undeniable erotic pull that Savage could probably never muster) than those of Tierney’s irresistible, ambivalent selfishness and immature longing—neither the concept of the character nor the actress’s performance has enough shading to make Madeleine a living, breathing person apart from the shadows of the designed-to-the-teeth noir landscapes in which she resides. She’s already as fatale as they come from that first entrance, so it’s no surprise when she ends up at the core of the movie’s (and, I assume, the book’s) obligatory attempt to provide some closure for audiences who, it is presumed, won’t want to leave the theater being reminded that the case remains unsolved in real life.

What is surprising though, after the movie’s overly determined pace and pall of self-importance begin sapping

The Black Dahlia of its narrative energy, is that De Palma still has one trick up his sleeve that made me pine for the kind of movie he might have made had he followed a different set of instincts. The movie spikes to life during the scene in which Bucky is introduced to Madeleine’s moneyed family—Daddy is a liquored-up Old Hollywood scumbag who became rich by selling off miles and miles of shoddy housing to Hollywood developers, Mother is a drunkenly repressed and thoroughly hostile gargoyle whose icy gaze seems dangerously turned both inward and outward at the same time, and Little Sister exudes fresh-scrubbed innocence as she quietly sketches during dinner, only to later reveal, amidst girlish giggles, her drawing of Bucky mounting Madeleine from behind, all harsh angles, entangled limbs melting into one another, full of rage. De Palma introduces the ghastly scene with what Matt Seitz accurately describes as one of the director’s great tracking shots, seen entirely from Bucky’s point of view as he follows Madeleine through the foyer, unable to ignore some of the ghastly decor of the Linscott house, to the scene’s dinner centerpiece. Matt observes that this horrifically comic interlude achieves the satiric tone De Palma shot for and missed in

The Bonfire of the Vanities, but I also thought of

Hi, Mom!, which was shot through with the kind of wickedly absurd humor that pays off with such goose-bump cackles here. (It’s often forgotten how

funny De Palma’s films are, and that his work routinely has much more of a satiric thrust than seems is ever much noted.) In fact, the unnerving gallows humor of the sequence, and Fiona Shaw’s fearless performance as Mrs. Linscott, a madwoman traipsing through a mental minefield who has yet to reveal the true depths of her madness in particular, had me hoping that De Palma would shuffle off the suffocating weight that enveloped the first third of the film and take us in a far more unexpected, disorienting direction. Unfortunately, the lure of spinning Ellroy’s hard-boiled detective fiction in a relatively straightforward manner proves irresistible to the director, who may be trying to find ways to expand his artistry by engaging in Ellroy’s speculative narrative, but who also forgets how to translate that search into fully engaging filmmaking, and by forgetting ends up, if the by-rote manner in which the movie concludes is any indication, disinterested in his own processes.

Both Ellroy’s book and De Palma’s movie exist in and, in the case of the film anyway, are products of an engagement with a culture, in its popular, sociological and psychological contexts, that puts an almost neurotic premium on closure. It’s not the conjecture about who killed Elizabeth Short that I object to, however, as much as it is the indifference with which it has been staged. When the big reveal happens at the end and Madeleine’s mother is unveiled as Short’s killer, with an assist from the silent, scarred gardener (played by De Palma veteran William Finley) who is also her secret lover, Shaw’s fearlessness seems to leap over into authentic madness, and her Grand Guignol gesticulating so redefines over-the-top that even Ken Russell might find her big moment slightly embarrassing. But the percolating sense of absurdity that underscored her only other moment, during the dinner scene, is overwhelmed by the muted self-seriousness that has scuttled the rest of the film’s drive, as well as its general effectiveness as drama, to the degree that I became indifferent to whatever was happening, high-pitched and screeching, or low-pitched and interior, so much so that the film’s big narrative moment comes across more as atonal flailing than a demonstration of moral horror.

One thing I never expected or demanded from any work of fiction dealing with the Black Dahlia mystery is that the crime be solved, and from the moment I heard of Ellroy’s book, I hoped and presumed that it would find a way to make the creeping malaise of which Short’s murder was but a symptom seep into the bones of his story—in fact, I was quite surprised to find out that Ellroy had delivered not an artfully rendered account of the murder and it’s subsequent investigation, but a politically conscious fiction built around that investigation. This is, of course, the framework that De Palma builds for his Ellroy adaptation as well, and it seems hardly fair to criticize the movie for also not being that work of speculative nonfiction.

But what De Palma has come up in realizing Ellroy seems so fundamentally unsatisfying that it’s hard for me not to think of how much more interesting a historically focused documentary dealing with the case facts, as well as what the Dahlia’s sad, vaporous spirit still means in the greater context of Hollywood’s template of corruption, might have been. This desire of mine was only heightened by Kirshner’s and De Palma’s success in dramatizing those painful audition films. The desperation of Short and the cat-and-mouse sadism of the director—voiced by De Palma—as seen in those sequences are palpable and powerful, and De Palma’s willingness to implicate himself, and the audience, as well as the cravenness of the movie industry in dealing out Short’s fate is nothing less than stunning. However much they are meant to reflect and inform the larger story, the threads spun here shame the tissue-thin theatrics of the rest of the movie.

In fact, it’s hard for me to shake the notion that the effect the movie as a whole has is to reduce an already humiliated, debased and violated woman to the level of a metaphor that doesn’t succeed in expanding the meaning of the complex, yet relatively bloodless story that has been constructed around it. Obviously, I don’t believe that it was Ellroy’s intent or De Palma’s to trivialize the murder of Elizabeth Short—the empathy they create for her in such a relatively short amount of time is remarkable, and De Palma’s style is suitably employed to ensure that we never think of this poor, mutilated woman as anything less than a human being. But in De Palma’s movie the moral quandary suffered by relatively shallow characters that don’t hold up under the weight of the ideas under which they were conceived is given the emphasis of importance. Consequently, the true horror of what happened to the woman who posthumously came to be known as the Black Dahlia comes uncomfortably close to being marginalized. It’s a bitter aftertaste that I didn’t expect coming from the man who was able to tear my heart out with the degree of empathy he created for Carrie White,

Dressed to Kill’s Kate Miller,

Blow Out’s Jack and Sally, and the Vietnamese girl at the black heart of

Casualties of War.

There’s also a bit of subtext to the debate among De Palma-philes over the merits of

The Black Dahlia that I think is worth mentioning. I’m a bit resistant to comments I’ve read over the weekend regarding the new De Palma film, ones not exclusively found on Matt’s blog, by the way, that imply that to not get with the program and see

The Black Dahlia as exactly a triumphant success or a key film in the De Palma canon is tantamount to pooh-poohing the director’s desire to expand his art. Or worse, to deny the power of the film is to insist that he keep repeating the same themes and cinematic techniques over and over again in pursuit of that special, recognizable De Palma excitement so that we might all keep having our giddy, fan boy fun, and too bad for him for wanting to expand his horizons and perversely dash our crude expectations. (Andrew Bemis, at

Cinevistaramascope, even posits the notion, adapted from Chuck Klosterman, that De Palma, a cinematic genius, is

“Advanced,” meaning that 99% of us just aren’t capable to getting what the director is up to with

The Black Dahlia. Perhaps, then, this theory could be employed to explain why De Palma’s

The Bonfire of the Vanities is the best movie of the ‘90s.) If anyone could get away with taking perverse pleasure in leaving the general audience behind, along with some fierce acolytes, I would expect it would be De Palma. But I would also expect to feel some of that pleasure myself, the thrill of a director discovering new avenues of expression that truly mean something to him.

The Black Dahlia doesn’t seem like work for hire—I don’t think De Palma is capable of hack work. It does feel like the work of a man who hasn’t quite figured out how to realize those desires to take his filmmaking in a different direction. Ironically, the signature De Palma set piece in

The Black Dahlia, a murder that takes place on a vertiginous, three-level staircase, has a musty, indifferent feel to it, as if even the director knows he’s gone to this well once too often, and that he’s doing the sequence because, well, what would a Brian De Palma movie be without it? Matt himself even left a comment that expressed concern that

The Black Dahlia is being judged in relation to what we expect from De Palma, and that such judgments seem unfair. But when the director undertakes another sequence like this staircase murder, essentially giving the audience what he imagines they want, judging De Palma in relation to his past doesn’t seem unfair because by staging this scene in the manner he does, De Palma invites the comparison himself.

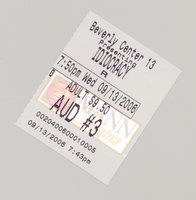

I was lucky enough to see

Carrie and

Dressed to Kill on a double feature at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Bing Theater last Friday night, one night after experiencing

The Black Dahlia. I am willing to acknowledge that many of De Palma’s films don’t look the same five or 10 or 20 years after their release, so I’m definitely open to revisiting

The Black Dahlia sometime in the future, maybe even the very near future, apart from all the initial grumbling and even the enthusiasm, to take a fresh look. (Every De Palma film I’ve seen, I’ve seen at least twice, with the exception of

Wise Guys and

Home Movies, and each time, for whatever reason, it’s been a good idea.)

And if

The Black Dahlia looks anywhere near as good 20 years from now as these two films do today, at 30 and 26 years old, respectively, then I’ll humbly eat my felt fedora. I was absolutely unprepared for how viscerally exciting it would be to see these particular films, each of which I’ve seen at least 10-15 times, on the big screen once again.

Carrie remains a brilliant shriek of hormonal hellfire, and it’s shot through with the excitement of a young filmmaker strengthening his own voice even as his draws inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock and others. Much has been said about the movie’s climactic prom sequence, from the initial conversations at Tommy and Carrie’s table, to the ballot box stuffing, to the couple’s agonizingly drawn-out approach to the stage, to the drenching of pig’s blood which draws the movie’s themes of unbridled menstrual, pubescent horrors tight around the viewer’s neck, to the apocalyptic catharsis of Carrie’s final explosion. Less has been noted, especially lately, about how the preceding hour seems only like a horror film when Carrie’s mother Margaret (Piper Laurie, unreservedly spectacular) is visiting the abuses of her religious fervor, which is hopelessly (and subconsciously) tangled up in the woman’s fear and repression of sex, upon her daughter. Otherwise, it’s a funny (sometimes uncomfortably so), sharp, and assuredly unsettling take on the kind of teen film that was all the rage in the drive-ins of the day, exploitation classics like

The Van and

The Pom Pom Girls, a movie blissfully unafraid of the kinds of tonal changes that would strike fear into the hearts of less fundamentally audacious directors.

Also, while I was knotted up in my seat Friday night in the moment directly after the daughter has been stabbed by her mother, and just before Carrie returns the favor by visiting an orgasmic crucifixion via telekinetically compelled kitchen implements upon Mrs. White, it struck me that there may never have been a character on screen for which I’ve had quite as much mainline empathy as I do for Carrie. She stares up at a woman barely recognizable as her mother, disbelieving and horrified as the lunatic approaches, a look of blissful dementia swimming across her face as she makes the signs of the cross above Carrie with a butcher knife, and my heart nearly irreparably breaks.

Carrie is classic De Palma, undiluted.

As is

Dressed to Kill, which for me was the biggest surprise of the night. I’ve always loved this movie, but over the course of the 26 years since its release I don’t think I’ve ever found it to be a pitch-perfect experience. Until last Friday night, that is.

Dressed to Kill seemed like such an undiluted 100 minutes of pure cinematic pleasure on that big screen (in a print that, if it wasn’t new, was in remarkable condition) that I almost felt like I’d never seen it before—given concessions to styles prevalent in 1980, when the movie was released,

Dressed to Kill still looks as pristine and clear as if it was made this year.

Every shot is designed to the hilt to maximize the pleasure De Palma gets from making a movie, a pleasure which is marvelously transmitted to the audience, and the movie clicks and whirs and glides like the biggest, most giddy clockwork toy you’ve ever seen. And that’s pretty amusing in and of itself, given its sensationally funny (you’re absolutely right, TLRHB!) take on our most lurid, often subconscious fears of the consequences of getting what we want—sex, attention, transformation— and then watching those desires spiral off into horrific, unexpected, but not, as many critics of the film continue to insist, morally mandated consequences. De Palma’s control of this material is awe-inspiring, and every element seems right—I could barely control my glee over seeing that spectacularly sustained museum sequence, the virtual wordlessness of which extends for almost a half hour, right up until the fateful elevator ride. What’s most memorable to me about that sequence, apart from the gut-wrenching horror of watching such a sympathetic character as Angie Dickinson’s Kate Miller dispatched so cruelly, are the individual moments-- like the killer holding out the razor toward Kate (the camera), all out of focus except for that extended, gleaming blade;

or Nancy Allen glimpsing that same killer in the elevator mirror, and that insinuating, erotically charged, diffuse, slow-motion close-close-close-up of Allen gazing up, not entirely computing what it is she’s seeing. I came away from the Bing Theater Friday night thinking of

Dressed to Kill as a genuinely perfect creation, and I was reminded once again about the difference that seeing a movie as thrilling as this one on a gigantic screen can make, and giving yourself over to the vision of a master director working at the top of his form.

And before I go, has there been enough credit given to Pino Donnagio over the past 30 years? This wonderful film composer, who has suffered accusations of picking Bernard Hermann’s carcass in much the same manner that De Palma has always been dogged by accusations of unabashedly stealing from Hitchcock, composed the scores for both of these films, and I don’t think his contributions to their success can possibly be overstated. As excited as I was to see De Palma’s films on the big screen, I was just as excited to hear once again Donaggio’s brilliant score for

Dressed to Kill on a sound system big enough that the stabbing violins and undulating undercurrents of the cellos and horns could properly resonate in my mind as well as in my chest cavity.

I almost went crazy with pleasure anticipating that moment near the end of

Dressed to Kill when Allen emerges from “the powder room” back into Dr. Elliot’s office, the flashes of lightning revealing Elliot now dressed as Bobbie, approaching her, in that gorgeous slow-motion, from the shadows behind. How wonderful to luxuriate once again in how much more terrifying the whole sequence is made by the contrapuntal spasms of horns and strings timed to explode with the cut to Allen staring toward the office window, agonizingly unaware of the presence just over and behind her right shoulder. Thank you, Mr. Donaggio.

I truly hope it’s not another 20 years before I get to see

Dressed to Kill, or

Carrie, on the big screen again. But if it is, I’ll always have Friday night to keep me motivated to not miss them when the opportunity comes around again, and to keep my hopes alive that whatever direction Brian De Palma takes as a filmmaker he can once again deliver a film, in whatever genre, guided by whatever formal dedications, that is as fully realized and unreservedly successful on an artistic level as either of these two.